“Two years now since we buried our mother in the grave. She was fifty-two years old when she died of a bad neck disease cervical cancer. She was sick for a short time, but we failed to recognize the disease that was troubling her, so we took her to many traditional healers. We spent money, we sold cattle, we bought medicine, but it didn’t help. In the end, when we managed to get some money, we took her to the big hospital in Mwanza—Bugando—to see if the doctors could help her. Even though the doctors examined her, they said, “This mother has cervical cancer.” We were very shocked, because she was in the prime of her life, about to be laid to rest.”

– A painful story from a young man who once heard about cancer after losing his aunt, who died from cervical cancer in 2022.

Cervical cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer deaths among women in the country, and it’s a growing threat in rural Tanzania, where over 70% of the population resides, yet access to preventive services is severely limited. With an estimated 40,000 new cases annually nationwide (projected to rise 80% by 2030), rural areas face burdens due to poverty, limited knowledge and/or awareness, and a centralized care system. A study conducted by Chelva M. (2024, August) found anassociation between low risk perception and limited knowledge on cervical cancer prevention, risk, symptoms, causes, and treatment, contributing to low screening uptake and, consequently, high cervical cancer mortality. These outcomes are in line with earlier findings, which established that ignorance and misconceptions about HPV and cervical cancer hinder early detection and prevention among women and adolescent girls. But there is hope. Cervical cancer is also one of only a few cancers for which a vaccine exists that may have a significant impact in reducing an individual’s risk.

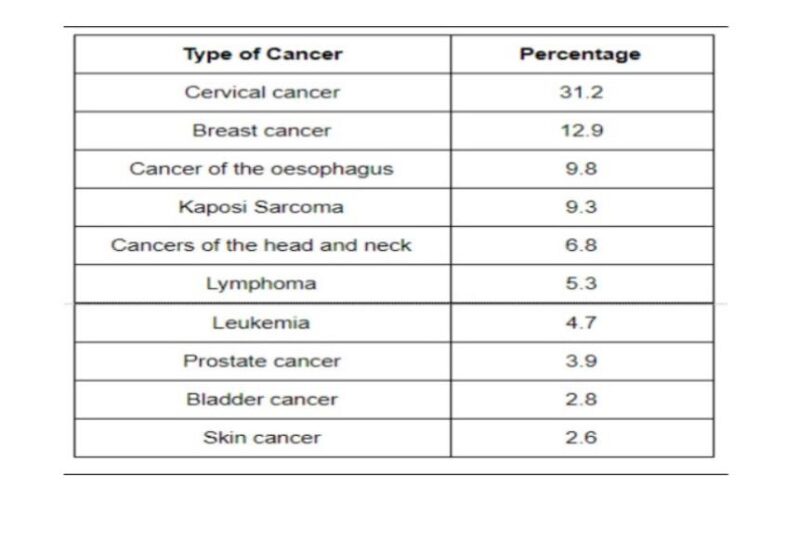

According to Statistics from Ocean Road Cancer Institute (ORCI) showed that cervical cancer accounted for 32.8% of all cancer cases diagnosed in 2018, followed by breast cancer at 12.9%, and Kaposi Sarcoma at 9.3%.

Additionally, Tanzania—where cervical cancer is the most common cancer nationally—has one of the highest incidence and death rates on the continent. Infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) is the main contributing risk factor for this cancer. In responding to the global health community’s endorsement of cervical cancer prevention by vaccinating girls aged 9–14, the Government of Tanzania launched an HPV vaccination initiative in 2014. Since October 2018, Tanzania become the seventh African nation to introduce the HPV vaccine into its routine immunization (RI) program, with the second dose administered to the first group of eligible girls.

Despite a significant stride in HPV Vaccination coverage for young girls in the country, reaching about 48% in the initial rollout, cost remains a major barrier that exacerbates inequities and hinders the goal of eliminating cervical cancer. To address these barriers, the Mwanza Intervention Trials Unit (MITU)—a collaborative unit under Tanzania’s National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)—has been at the forefront of groundbreaking research that informs health policy changes with high evidence in Tanzania ( You may visit their website here)

MITU and LSHTM’s inaugural HPV vaccine trial, the “DoRIS trial,” launched around 2016–2017 as an open-label, individually randomized controlled study specifically among adolescent girls in Northwest Tanzania( You may read about the study here).This was a pioneering effort to test whether a “single-dose schedule” of HPV vaccines could be as effective as the standard multi-dose regimen, directly tackling cost and logistics barriers such as ensuring follow-up doses in remote areas. However, DoRIS has influenced both national and global guidelines, including the “Single-Dose HPV Vaccine Evaluation Consortium”, and it has helped Tanzania consider single-dose integration into its national program.

In a recent pilot conducted at Mwamanga Village in Northwest Tanzania by a team from MITU as part of the IMPROVE HPV Research study that aims at measuring the impact of offering male vaccination on HPV Vaccination uptake through the national programme in females, offers a beacon of hope, illustrating how community-driven efforts can catalyze health policy change to combat the preventable disease. By engaging community members, village leaders, health workers, and families, the pilot fostered a participatory model that aligns with broader frameworks like Tanzania National Cancer Strategy (2016–2020, extended to 2025) and the Health Sector Strategic Plan V (2021/22–2025/26). These frameworks emphasize community outreach to bridge urban-rural disparities, a goal the Mwamanga pilot advances through localized education and policy advocacy.

Photo: Community Engagement meeting at Mwamanga Village

As a clinical Researcher, it was a reminder that meaningful community engagement is important to have their voices and providecontextual knowledge, identifying barriers like low-risk perception and addressing cultural myths. This enhances community sensitization and mobilization in village research studies.

However, Grassroot Education and Advocacy, by leveraging the local language (Sukuma), is essential to deliver targeted HPV education/message, addressing misconceptions—like the belief that cancer is a “curse”. This will shift cultural norms, encouraging community-wide support for female uptake, which informs policies to integrate gender-inclusive strategies.

Challenges and Opportunities

The article highlights persistent challenges, including high costs, low awareness, and centralized care systems that delay diagnosis, which have been observed in rural communities. Only 9% of rural facilities offer cancer services, exacerbating inequities. Yet, the pilot reveals opportunities for Community Health Workers (CHWs) involvement in NCD prevention (Cancer included). CHWs are essential components of the public health workforce, delivering primary healthcare at the household level; therefore, there’s a potential need for their inclusion in screening and mobilizing the community on vaccination uptake, cancer prevention, and community-led advocacy for policy integration of single-dose vaccines.

Conclusion

This pilot serves more as a form of community engagement; it is a call to amplify community voices for a better and healthier population. The Mwamanga pilot, like the broader initiatives in rural Tanzania, underscores that communities are not passive recipients but active architects of health policy change. Their participation in research shapes evidence, and their resilience drives equitable access to healthcare for all.

Written by Josephat Maseke Raphael, Research Assistant for IMPROVE HPV Project at Mwanza Interventional Trials Unit (MITU)/ NIMR Mwanza Centre.