This article provides a comprehensive overview of oligodendroglioma, a rare but well-defined subtype of diffuse glioma characterized by its distinct molecular signature—IDH mutation and 1p/19q codeletion. We explore the clinical presentation, diagnostic criteria based on the 2021 WHO CNS classification, treatment strategies for both grade 2 and grade 3 tumors, and the long-term outcomes informed by key clinical trials. With improved molecular diagnostics and evolving therapeutic options, understanding oligodendroglioma is essential for delivering personalized, evidence-based care in neuro-oncology.

What Is Oligodendroglioma?

Oligodendroglioma is a rare type of brain tumor that develops from oligodendrocytes, the cells that produce and maintain myelin, which insulates nerve fibers in the central nervous system. These tumors are typically slow-growing and can occur in various parts of the brain, most commonly in the frontal lobes. They often present with symptoms such as seizures, headaches, or changes in cognition or behavior, depending on their size and location. Oligodendrogliomas are diffusely infiltrative, meaning they spread into surrounding brain tissue, which can make complete surgical removal difficult.

Types and Classification of Oligodendroglioma

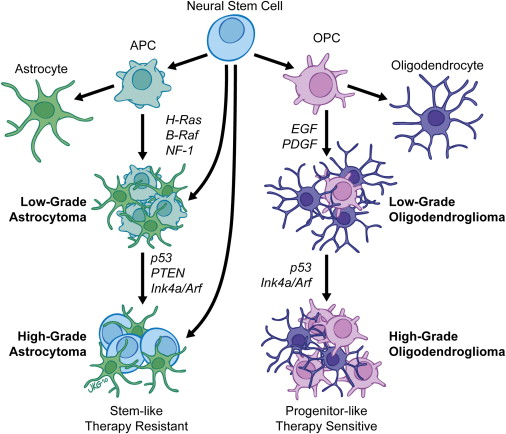

Oligodendrogliomas are classified as diffuse gliomas, meaning they infiltrate the surrounding brain tissue rather than forming a distinct, encapsulated mass. Their classification has evolved significantly with the incorporation of molecular diagnostics, especially in the 2021 World Health Organization (WHO).

Under the current WHO system, a tumor is classified as oligodendroglioma only if it meets the following molecular criteria:

- IDH mutation (either in the IDH1 or IDH2 gene)

- 1p/19q codeletion (a combined deletion of the short arm of chromosome 1 and the long arm of chromosome 19)

Both features must be present. Tumors that are IDH-mutant but lack 1p/19q codeletion are classified as astrocytomas, not oligodendrogliomas.

Once confirmed, oligodendrogliomas are further graded histologically:

- Oligodendroglioma, WHO Grade 2

These tumors are lower grade, typically slow-growing, with fewer mitoses and no microvascular proliferation or necrosis. They often have an indolent course and better prognosis.

- Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma, WHO Grade 3

These are more aggressive, with increased cellularity, mitotic activity, and sometimes microvascular proliferation and necrosis. They are associated with a higher risk of recurrence and a shorter time to progression compared to Grade 2 tumors.

The grade of the tumor, along with its molecular features, plays a critical role in determining treatment strategies and prognosis (Louis et al., 2021; Wesseling & Capper, 2021).

Read More About Brain Cancer on Oncodaily

Risk Factors for Oligodendroglioma

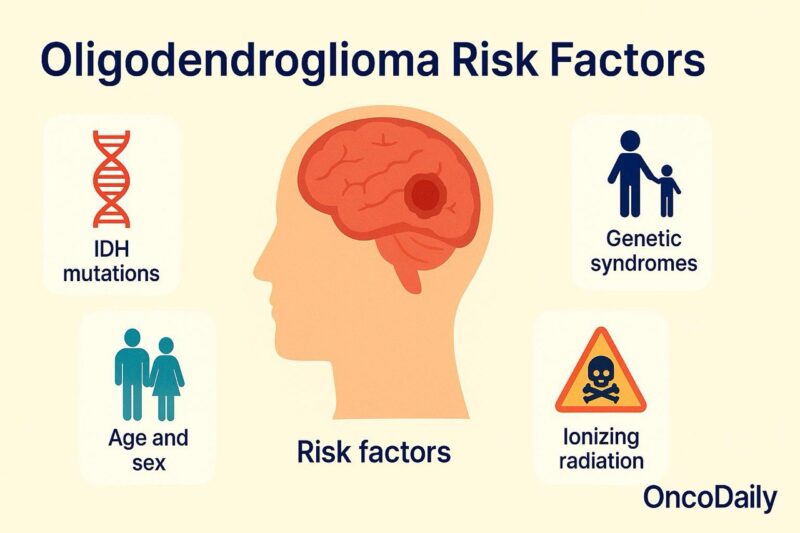

Oligodendroglioma is a rare type of primary brain tumor, and its underlying causes are not fully understood. However, several factors—both molecular and demographic—have been associated with its development. At the cellular level, virtually all oligodendrogliomas harbor mutations in the IDH1 or IDH2 genes, along with a combined deletion of chromosome arms 1p and 19q. These alterations are not inherited in most patients but occur spontaneously during early tumorigenesis. They are not only diagnostic hallmarks but also contribute to the tumor’s behavior and responsiveness to treatment (Louis et al., 2021).

Demographic data suggest that oligodendroglioma most commonly affects adults between the ages of 30 and 50, with a slight predominance in males. Although the reasons for this sex difference remain unclear, it has been observed consistently in epidemiologic studies (Ohgaki & Kleihues, 2005).

In rare cases, genetic cancer predisposition syndromes such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome or Turcot syndrome may increase the risk of gliomas, including oligodendroglioma. However, these inherited conditions are more frequently associated with astrocytic or embryonal tumors and account for only a minority of oligodendroglioma cases. Exposure to ionizing radiation, particularly in childhood, is one of the few environmental risk factors with consistent evidence. Individuals treated with cranial radiation for prior malignancies or benign conditions (such as tinea capitis) may have an increased risk of developing gliomas later in life, including oligodendrogliomas (Preston et al., 2007).

Speculation about other environmental contributors—such as pesticide exposure, industrial chemicals, or cell phone radiation—has been raised, but large population studies have not confirmed any direct or consistent associations with oligodendroglioma specifically. In summary, while molecular alterations define the tumor itself, the risk factors for developing oligodendroglioma are largely non-modifiable and not fully elucidated. Current research continues to explore potential genetic, epigenetic, and environmental contributors to its pathogenesis.

Symptoms of Oligodendroglioma

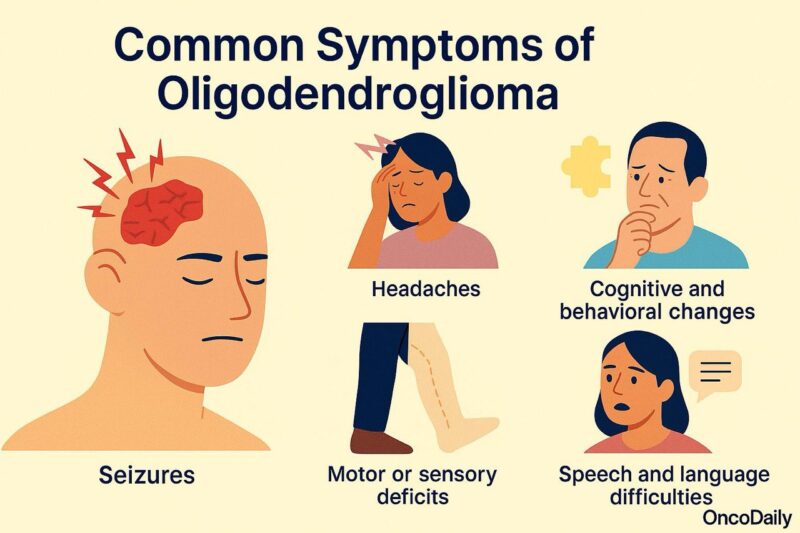

The symptoms of oligodendroglioma depend on the tumor’s location, size, and growth rate, but they often develop gradually due to the slow-growing nature of the tumor. Most oligodendrogliomas arise in the frontal lobes, which play a key role in behavior, personality, and motor function.

Common symptoms of oligodendroglioma include:

Seizures: This is often the first and most frequent symptom, occurring in up to 80% of patients. Seizures may be focal (affecting one part of the body) or generalized.

Headaches: Caused by increased intracranial pressure or mass effect, headaches may be persistent and worse in the morning or with changes in position.

Cognitive and behavioral changes: Depending on the frontal lobe involvement, patients may experience difficulty with concentration, memory loss, personality shifts, apathy, or mood disturbances.

Motor or sensory deficits: If the tumor affects areas near the motor or sensory cortex, patients may develop weakness, numbness, or clumsiness on one side of the body.

Speech and language difficulties: Tumors involving the dominant hemisphere may lead to problems with speaking, understanding language, or word-finding.

Because symptoms can be subtle and progress slowly, diagnosis is sometimes delayed until seizures or noticeable neurological changes prompt imaging studies.

Diagnosis of Oligodendroglioma

The diagnosis of oligodendroglioma involves a combination of clinical evaluation, neuroimaging, histopathology, and molecular testing. Accurate diagnosis is essential because treatment decisions and prognosis are strongly influenced by both the tumor’s histologic grade and its molecular profile.

Clinical Evaluation

The diagnostic process often begins when patients present with seizures, headaches, or neurological symptoms. A detailed neurological examination and symptom history guide the next steps.

Neuroimaging

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is the preferred imaging modality:

- T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences typically show a hyperintense, infiltrative lesion.

- Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images may show no enhancement (in low-grade tumors) or heterogeneous enhancement (in higher-grade tumors).

- Calcifications, common in oligodendrogliomas, are better seen on CT scans.

Tumors are often well-circumscribed on imaging but histologically diffuse.

Surgical Biopsy or Resection

A tissue sample is necessary for definitive diagnosis. Depending on tumor location and size, neurosurgeons may perform a biopsy or aim for maximal safe resection. The tumor is then evaluated under the microscope for features such as:

- Cellular uniformity with round nuclei

- “Fried egg” appearance due to perinuclear halos

- Delicate branching capillaries (“chicken wire” vascular pattern)

Molecular Testing

The 2021 WHO CNS tumor classification requires confirmation of two molecular features for the diagnosis of oligodendroglioma:

- IDH1 or IDH2 mutation: Usually tested via immunohistochemistry or sequencing.

- 1p/19q codeletion: Confirmed using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), PCR, or next-generation sequencing.

If either of these is absent, the tumor is not considered an oligodendroglioma.

Additional Markers

Other markers that may be assessed for diagnostic or prognostic purposes include:

- ATRX (retained in oligodendroglioma, lost in astrocytoma)

- TP53 (rarely mutated in oligodendroglioma)

- Ki-67 (MIB-1) index, to assess proliferative activity

Together, histologic and molecular features provide a layered diagnosis, aligning with WHO recommendations (Louis et al., 2021).

Treatment of Oligodendroglioma

The treatment of oligodendroglioma is guided by the tumor’s grade, location, and molecular features—particularly the presence of an IDH mutation and 1p/19q codeletion, which define this tumor subtype under the WHO 2021 CNS classification. Management strategies also consider patient-specific factors such as age, functional status, and symptom burden.

Surgical resection is the first step in management for most patients. The goal is to achieve maximal safe tumor removal, both to reduce mass effect and to provide tissue for definitive histopathological and molecular diagnosis. In some patients with small, asymptomatic, and low-grade (WHO grade 2) tumors, especially when a gross total resection is achieved, initial postoperative surveillance may be appropriate (van den Bent et al., 2005). However, many patients require further treatment based on residual disease, age, or symptomatic presentation.

When adjuvant therapy is indicated—particularly in grade 3 (anaplastic) tumors or incompletely resected grade 2 tumors—the combination of radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy has become the standard approach. The chemotherapy of choice is the PCV regimen (procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine), which has demonstrated significant survival benefits in two landmark trials: RTOG 9402 and EORTC 26951. Both studies confirmed that the addition of PCV to radiation improves progression-free survival and overall survival in patients with IDH-mutant, 1p/19q-codeleted tumors (Cairncross et al., 2013; van den Bent et al., 2013).

Read More About Radiotherapy for Brain Tumors on Oncodaily

While temozolomide is often used in clinical practice due to its ease of administration and tolerability, it has not yet shown equivalent long-term survival benefit to PCV in randomized trials for oligodendroglioma.

Regular MRI follow-up every 3–6 months is essential to monitor for recurrence or progression, especially in the first several years post-treatment. Given the relatively favorable long-term prognosis in many cases—particularly in patients with grade 2 tumors and favorable molecular markers—attention to the long-term effects of therapy, including neurocognitive decline and treatment-related toxicity, is increasingly important in survivorship care.

Prognosis of Oligodendroglioma

Oligodendroglioma is considered one of the more favorable forms of diffuse glioma in terms of long-term outcomes, particularly when defined by its molecular signature—IDH mutation and 1p/19q codeletion. These features not only aid in diagnosis but are also strong positive prognostic markers (Louis et al., 2021).

Patients with WHO grade 2 oligodendroglioma often experience an indolent clinical course, with median overall survival exceeding 14–16 years in many cases, especially when optimal treatment (surgery plus radiotherapy and PCV chemotherapy) is applied (van den Bent et al., 2013). Seizure control is often excellent with resection and adjuvant therapy, and many patients maintain functional independence for years.

For WHO grade 3 (anaplastic oligodendroglioma), the disease behaves more aggressively but still offers a relatively prolonged survival compared to other high-grade gliomas. Median survival ranges from 8 to 12 years, depending on patient age, performance status, extent of resection, and response to therapy (Cairncross et al., 2013).

The most critical prognostic factors include:

- IDH mutation and 1p/19q codeletion (defining and favorable)

- Extent of surgical resection

- Age at diagnosis (younger patients do better)

- Histologic grade

- Treatment response to radiotherapy and PCV chemotherapy

While recurrence is common, oligodendrogliomas often respond well to repeat treatment. However, transformation into a more aggressive phenotype (e.g., therapy-resistant grade 3 disease) can occur in later stages. Ongoing monitoring with MRI and, increasingly, molecular surveillance via liquid biopsy is essential for early detection of progression.

The Role of Immunotherapy for Oligodendroglioma

Immunotherapy has transformed the treatment landscape of many solid tumors, particularly through the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 pathways. However, its role in oligodendroglioma remains limited, exploratory, and largely investigational.

Unlike glioblastoma and other high-grade astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas typically have low mutational burden, less immune cell infiltration, and limited expression of PD-L1, all of which are factors associated with reduced responsiveness to immunotherapy (Reardon et al., 2016). These tumors tend to be more immunologically “cold,” meaning they provoke less immune recognition and are less likely to benefit from checkpoint blockade alone.

To date, there are no approved immunotherapy agents for oligodendroglioma, and most clinical trials investigating immune checkpoint inhibitors—such as nivolumab or pembrolizumab—have focused on glioblastoma or IDH-wildtype astrocytomas. That said, some trials have included IDH-mutant gliomas as exploratory cohorts, and ongoing research is evaluating whether combinations of immunotherapy with radiation, IDH inhibitors, or vaccines may help overcome immune resistance in these tumors.

One promising area of investigation involves IDH mutations, which produce the oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG). This metabolite may suppress local immune responses, and preclinical studies suggest that targeting mutant IDH may reverse this immunosuppressive environment and enhance immune activation (Zhao et al., 2019).

Read More About Immunotherapy for Brain Cancer on Oncodaily

2025 Advances in Oligodendroglioma

In 2025, the management of oligodendroglioma continues to progress beyond traditional standards of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. Emerging research is refining the use of molecularly targeted agents, enhancing the role of immunotherapy, and improving long-term monitoring approaches—particularly in the context of IDH-mutant, 1p/19q-codeleted gliomas.

IDH Inhibition and Vorasidenib

Following the pivotal INDIGO trial, vorasidenib—a dual IDH1/IDH2 inhibitor with central nervous system penetration—received FDA approval in 2024 for adults and adolescents with IDH-mutant, grade 2 diffuse gliomas who have not yet received radiation or chemotherapy (Mellinghoff et al., 2023). Although the INDIGO trial focused on astrocytomas, similar molecular mechanisms underlie oligodendrogliomas, prompting interest in extending IDH inhibition to this subgroup. Ongoing 2025 trials are evaluating vorasidenib in oligodendroglioma to determine whether early intervention can delay the need for cytotoxic therapy and preserve cognitive function.

Immunotherapy and Combination Strategies

Despite limited efficacy of single-agent checkpoint inhibitors in gliomas, new combination approaches are being explored in IDH-mutant gliomas, including oligodendrogliomas. Preclinical studies show that IDH mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), which contributes to local immunosuppression (Zhao et al., 2019). Trials initiated in late 2024 are testing combinations of PD-1 inhibitors with IDH inhibitors or histone deacetylase inhibitors to reverse immune evasion and enhance T-cell activation.

IDH1-Targeted Vaccines

Efforts are also underway to develop neoantigen vaccines targeting mutant IDH1 (R132H), which is present in nearly all oligodendrogliomas. Early-phase studies in Europe and North America are assessing safety and immunogenicity of peptide vaccines designed to elicit cytotoxic T-cell responses against IDH1-mutant cells (Platten et al., 2021). While efficacy data remain pending, these strategies represent a tailored, tumor-specific immunotherapy approach.

Liquid Biopsy and Molecular Monitoring

With the goal of earlier and less invasive detection of tumor progression, liquid biopsy techniques are being refined to track IDH-mutant circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in blood and cerebrospinal fluid. In 2025, several centers are validating platforms that detect IDH1/IDH2 mutations and 1p/19q loss in plasma, which may allow for longitudinal surveillance without relying solely on MRI imaging (Piccioni et al., 2023).

Survivorship and Cognitive Preservation

As oligodendroglioma patients often live more than a decade post-diagnosis, quality of life and cognitive outcomes are increasingly central to treatment planning. New clinical protocols in 2025 emphasize risk-adapted approaches, including reduced-dose radiotherapy and chemotherapy de-escalation in low-risk, completely resected tumors. Neurocognitive assessments and survivorship care models are being standardized at academic centers (Taphoorn et al., 2022).

You Can Watch More on OncoDaily Youtube TV

Written by Armen Gevorgyan, MD

FAQ

What is oligodendroglioma?

Oligodendroglioma is a rare type of brain tumor that originates from oligodendrocytes—cells responsible for producing the myelin sheath that insulates nerve fibers. It typically occurs in adults and is defined by two key molecular features: an IDH mutation and a 1p/19q codeletion.

What are the symptoms of oligodendroglioma?

Common symptoms include seizures, headaches, personality or cognitive changes, motor weakness, and speech difficulties. Symptoms depend on the tumor’s size and location, often in the frontal lobe.

How is oligodendroglioma diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves brain MRI, followed by surgical biopsy or resection. The tumor is confirmed histologically and must show both an IDH mutation and 1p/19q codeletion to meet WHO criteria.

What is the difference between grade 2 and grade 3 oligodendroglioma?

Grade 2 tumors grow slowly and have fewer aggressive features, while grade 3 (anaplastic) tumors are more cellular, mitotically active, and may show necrosis. Grade 3 tumors carry a higher risk of recurrence and require more aggressive treatment.

What treatments are available for oligodendroglioma?

Standard treatment includes maximal safe surgical resection, followed by radiation therapy and PCV chemotherapy, particularly for grade 3 or incompletely resected tumors.

What is the prognosis for patients with oligodendroglioma?

Prognosis is generally favorable, especially for grade 2 tumors. Median survival for well-managed cases can exceed 10–15 years, particularly when IDH mutation and 1p/19q codeletion are present.

How often do oligodendrogliomas recur?

Recurrence is common over time, even in low-grade tumors. Regular MRI monitoring every 3–6 months is recommended to detect regrowth or malignant transformation.

Is oligodendroglioma hereditary?

Most cases are sporadic and not inherited. Rarely, it may occur in people with genetic syndromes like Li-Fraumeni or Turcot syndrome, but this is uncommon.

Can immunotherapy treat oligodendroglioma?

Immunotherapy is not yet standard for oligodendroglioma, but research is ongoing. Trials are exploring checkpoint inhibitors and IDH-targeted vaccine therapies.

What are the recent advances in oligodendroglioma treatment?

Recent progress includes FDA approval of IDH inhibitors like vorasidenib, exploration of immunotherapy combinations, and development of liquid biopsies for non-invasive monitoring.