This article provides an up-to-date, in-depth overview of cholangiocarcinoma (bile duct cancer) as of 2025. It covers the latest knowledge on risk factors, causes, and early warning signs, as well as the most effective diagnostic techniques and treatment strategies. Readers will find detailed information about current surgical options, systemic therapies—including chemotherapy, targeted drugs, and immunotherapy—and the impact of precision medicine through molecular profiling. The article also highlights recent FDA approvals, ongoing and emerging clinical trials, advances in personalized and locoregional therapies, and evolving patient outcomes. Whether you are a patient, caregiver, or healthcare professional, this resource is designed to help you understand the most important developments in cholangiocarcinoma care and research today.

What Is Cholangiocarcinoma?

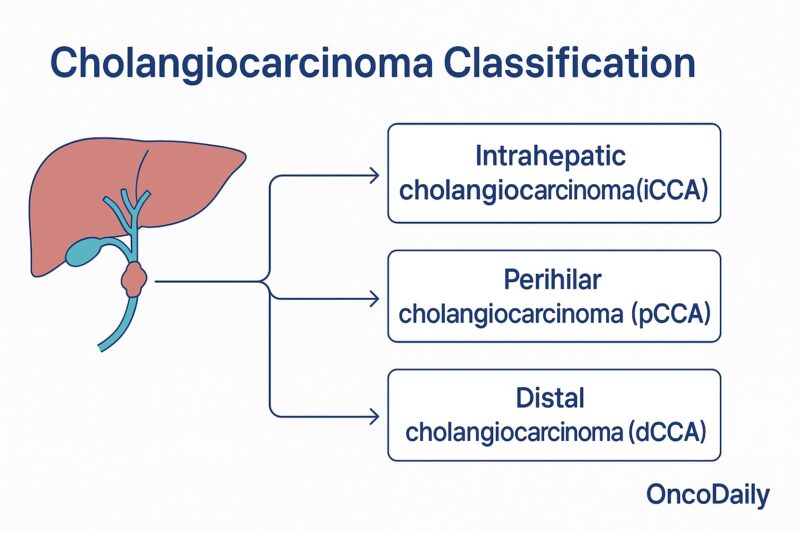

Cholangiocarcinoma is a rare and aggressive cancer that originates in the cells lining the bile ducts—the slender tubes that transport bile from the liver to the gallbladder and small intestine. This cancer is sometimes called “bile duct cancer” (Razumilava & Gores, N Engl J Med, 2014). Cholangiocarcinoma can develop anywhere along the bile duct system, which is divided into three main regions: intrahepatic (within the liver), perihilar (where the right and left bile ducts join just outside the liver), and distal (further down the bile duct near the small intestine) (Banales et al., Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020).

Classification of Cholangiocarcinoma

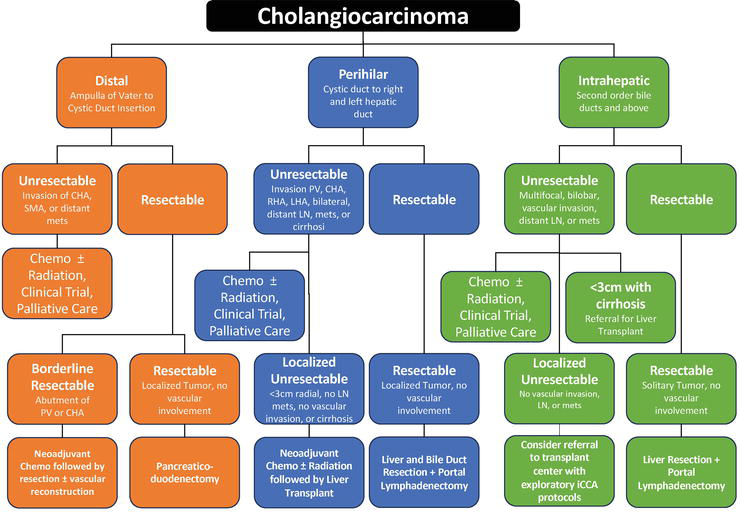

Cholangiocarcinoma is classified based on its anatomical location within the bile duct system. The three main types are:

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma arises from the small bile ducts located within the liver. Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (also called Klatskin tumor) occurs at the hilum, where the right and left hepatic ducts join just outside the liver. Distal cholangiocarcinoma develops in the bile ducts further down, near where the bile duct enters the small intestine.

This classification is important because each type has distinct risk factors, clinical presentations, and treatment approaches (Razumilava & Gores, N Engl J Med, 2014; Banales et al., Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020).

Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma originates in the small bile ducts located within the liver itself. It accounts for about 10–20% of all cholangiocarcinomas. This type is often diagnosed at an advanced stage, since early symptoms are non-specific or absent. Patients may present with vague abdominal discomfort, weight loss, or liver dysfunction. Risk factors include chronic liver diseases such as hepatitis B or C, cirrhosis, and certain parasitic infections. Treatment usually involves surgery if the tumor is resectable, but many cases require chemotherapy or targeted therapy due to late diagnosis (Razumilava & Gores, N Engl J Med, 2014).

Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, also called Klatskin tumor, arises at the junction where the right and left hepatic bile ducts meet just outside the liver. It is the most common form of cholangiocarcinoma, representing 50–60% of cases. These tumors typically cause bile duct obstruction, leading to symptoms like jaundice, itching, and dark urine. Underlying risk factors include primary sclerosing cholangitis and congenital bile duct abnormalities. Surgery is often complex, sometimes requiring liver transplantation, and additional therapies such as biliary drainage or chemotherapy are frequently used (Banales et al., Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020).

Distal Cholangiocarcinoma

Distal cholangiocarcinoma develops in the bile ducts located closer to the small intestine, further down from the liver. It comprises about 20–30% of cholangiocarcinomas. Symptoms most often result from bile duct blockage, including jaundice and digestive issues. Risk factors are similar to those for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Treatment usually involves surgical removal of the affected bile duct segment and part of the pancreas (Whipple procedure), sometimes followed by chemotherapy or radiation therapy, depending on disease stage (Razumilava & Gores, N Engl J Med, 2014; Banales et al., Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020).

Causes of Cholangiocarcinoma

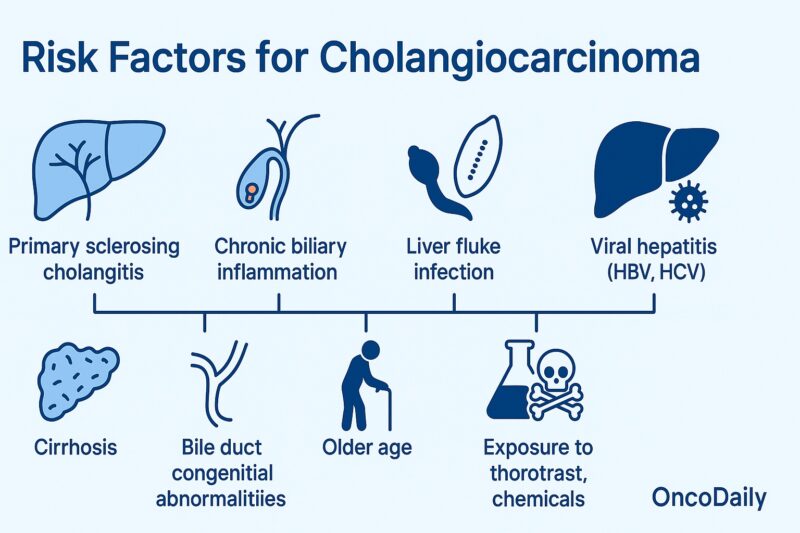

Cholangiocarcinoma develops when the cells lining the bile ducts become cancerous, often due to chronic inflammation or injury. One of the most significant risk factors is primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), a disease that causes progressive scarring and inflammation of the bile ducts. In certain regions, particularly Southeast Asia, liver fluke infections (from parasites such as Opisthorchis viverrini or Clonorchis sinensis) are major contributors to the disease due to the chronic inflammation they cause in the bile ducts. Other risk factors include chronic biliary inflammation (from recurrent bile duct stones or bacterial infections), congenital abnormalities of the bile ducts (like choledochal cysts and Caroli disease), and chronic viral hepatitis (B or C) or cirrhosis, which increase the risk for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Exposure to certain chemicals, such as thorotrast and dioxins, though rare today, has also been associated with this cancer. Metabolic conditions like obesity, diabetes, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease may further contribute, likely due to their link to ongoing liver inflammation. Despite these associations, many cases of cholangiocarcinoma arise without any clear cause, reflecting a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and idiopathic factors (Razumilava & Gores, N Engl J Med, 2014; Banales et al., Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020).

Symptoms of Cholangiocarcinoma

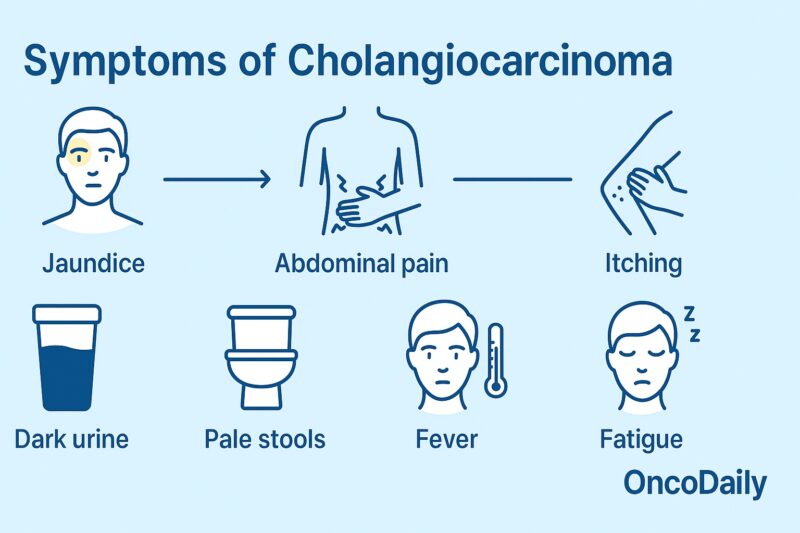

Cholangiocarcinoma symptoms vary depending on the location of the tumor within the bile duct system. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, which arises from bile ducts inside the liver, often causes subtle or non-specific symptoms in the early stages. Patients may experience vague right upper abdominal discomfort, unexplained weight loss, fatigue, or, less commonly, fever and night sweats. Jaundice is unusual in early intrahepatic tumors and usually appears only if the tumor grows large enough to obstruct the major bile ducts (Razumilava & Gores, N Engl J Med, 2014).

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klatskin tumor), which forms at the junction of the right and left hepatic ducts, is the most common type. It frequently causes painless jaundice as an early symptom due to bile duct obstruction. Other common signs include dark urine, pale stools, itching (pruritus), and, as the disease advances, weight loss and abdominal pain. Because the tumor is close to the liver’s main drainage point, jaundice often develops early in the course of perihilar disease (Banales et al., Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020).

Distal cholangiocarcinoma, found in the lower part of the bile duct near the small intestine, typically presents with symptoms of biliary obstruction as well. Patients may notice yellowing of the skin and eyes, dark urine, light-colored stools, and itching. Abdominal pain, loss of appetite, and weight loss can also occur. These symptoms are similar to those of perihilar tumors but may also overlap with pancreatic and other periampullary cancers due to the location (Razumilava & Gores, N Engl J Med, 2014).

Because early symptoms are often vague and non-specific—especially for intrahepatic tumors—many patients are diagnosed at a late stage, after jaundice, weight loss, or abdominal pain prompt medical evaluation.

Diagnosis of Cholangiocarcinoma

Diagnosing cholangiocarcinoma requires a combination of clinical evaluation, laboratory testing, and imaging studies. Because symptoms often overlap with other biliary and liver diseases, the process can be complex and may require multiple steps.

Blood tests are usually performed first and may reveal elevated levels of bilirubin and liver enzymes, reflecting bile duct obstruction or liver dysfunction. Tumor markers such as CA 19-9 and CEA can be elevated in many cases, but these are not specific for cholangiocarcinoma and are mainly used to support the diagnosis or monitor response to treatment.

Imaging studies play a central role in both diagnosis and staging. Ultrasound is often the initial imaging test to detect biliary obstruction or liver masses. Contrast-enhanced CT scans and MRI with MRCP (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography) provide more detailed images, allowing visualization of the bile ducts, assessment of tumor extent, and detection of metastases.

Endoscopic procedures such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) may be used to directly visualize the bile ducts, obtain brushings or biopsies, and sometimes place stents to relieve obstruction. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) is another option if endoscopic access is not possible.

A definitive diagnosis is made by obtaining tissue samples through biopsy or brush cytology, often during ERCP, EUS, or PTC. However, due to the location and nature of these tumors, tissue diagnosis may sometimes be challenging.

In some cases, genetic and molecular testing of the tumor can help identify mutations or biomarkers that guide targeted therapy (Razumilava & Gores, N Engl J Med, 2014; Banales et al., Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020).

Prognosis of Cholangiocarcinoma

The prognosis for cholangiocarcinoma is generally poor, mainly because most cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage when curative surgery is not possible. Survival rates depend on the tumor’s location, stage at diagnosis, and whether complete surgical removal (resection) can be achieved.

For patients with early-stage, resectable cholangiocarcinoma, five-year survival rates range from 20% to 40%, with the best outcomes seen in those who undergo successful surgery with clear margins (Razumilava & Gores, N Engl J Med, 2014). However, the majority of patients present with unresectable or metastatic disease, for which the five-year survival rate is less than 10% (Banales et al., Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020).

Recurrence after surgery is common, even in patients who initially achieve complete resection. Prognosis tends to be worse for perihilar and distal tumors compared to intrahepatic types, and certain molecular or genetic features—such as mutations in IDH1 or FGFR2—can influence the disease course and treatment options.

Advances in targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and improved supportive care are gradually improving outcomes for some patients, but early detection remains key for a better prognosis.

Treatment of Cholangiocarcinoma

The management of cholangiocarcinoma is complex and requires a multidisciplinary approach, as most patients present with advanced disease that is difficult to cure. Treatment strategies depend on tumor location (intrahepatic, perihilar, or distal), stage at diagnosis, molecular profile, and the patient’s overall health. Options include surgery, systemic therapies, locoregional therapies, radiation, and supportive or palliative care. Recent advances in molecular profiling have led to the development of targeted therapies and immunotherapies, further expanding the landscape of treatment.

Surgery

Surgical resection is the only potentially curative treatment for cholangiocarcinoma, but only a minority of patients are candidates for surgery at diagnosis due to advanced stage or poor underlying liver function.

- Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is treated with partial liver resection, often accompanied by lymph node dissection. Complete tumor removal (R0 resection) offers the best chance for long-term survival, but recurrence rates remain high.

- Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma often requires complex surgery, such as bile duct resection, major liver resection, and sometimes vascular reconstruction. Liver transplantation is an option for highly selected patients with early, unresectable perihilar tumors following neoadjuvant therapy (Razumilava & Gores, N Engl J Med, 2014).

- Distal cholangiocarcinoma is typically managed with pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure), removing the lower bile duct, gallbladder, part of the pancreas, and part of the small intestine.

Even after complete resection, recurrence is common, so postoperative (adjuvant) therapy is often recommended.

Adjuvant and Neoadjuvant Therapy

Adjuvant therapy is given after surgery to reduce the risk of recurrence.

- The BILCAP study established capecitabine as the standard adjuvant chemotherapy for resected biliary tract cancers, improving overall survival compared to observation alone.

- Chemoradiation may be considered in patients with positive margins or lymph node involvement (Kelley et al., J Clin Oncol, 2020).

Neoadjuvant therapy, which is treatment given before surgery, is less commonly used but may be considered in select cases (especially for liver transplantation in perihilar tumors), using combinations of chemotherapy and radiation to shrink the tumor.

Systemic Therapy for Advanced Disease

Most patients are diagnosed with advanced, unresectable, or metastatic disease and require systemic therapy as the mainstay of treatment.

- First-line therapy: Gemcitabine + Cisplatin + Durvalumab: This combination is now considered the preferred first-line regimen. The addition of durvalumab, an anti–PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, to gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy has demonstrated improved overall survival and progression-free survival compared to chemotherapy alone. This recommendation is based on the results of the TOPAZ-1 trial, a phase III study that showed a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in overall survival for patients receiving the triplet combination.

- Second-line therapy: For patients who progress on first-line treatment, FOLFOX (oxaliplatin, 5-FU, leucovorin) has demonstrated modest benefits.

- Other chemotherapy combinations (e.g., gemcitabine/oxaliplatin, capecitabine/oxaliplatin) may also be considered (Banales et al., Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020).

Targeted Therapy

Molecular profiling has revealed actionable mutations in a subset of cholangiocarcinomas, leading to new targeted treatments:

- FGFR2 fusions/rearrangements (mainly in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma) can be treated with FGFR inhibitors such as pemigatinib, futibatinib, and infigratinib.

- IDH1 mutations are targeted by the oral inhibitor ivosidenib.

- Other targets under investigation include BRAF V600E, HER2 amplification, NTRK fusions, and ROS1 fusions.

- For tumors with microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair deficiency, immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab can be effective (Kelley et al., J Clin Oncol, 2020).

Read More About Ivosidenib on Oncodaily

These targeted approaches are now standard for patients with advanced disease who harbor these molecular alterations, and molecular testing is recommended for all patients with unresectable or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma.

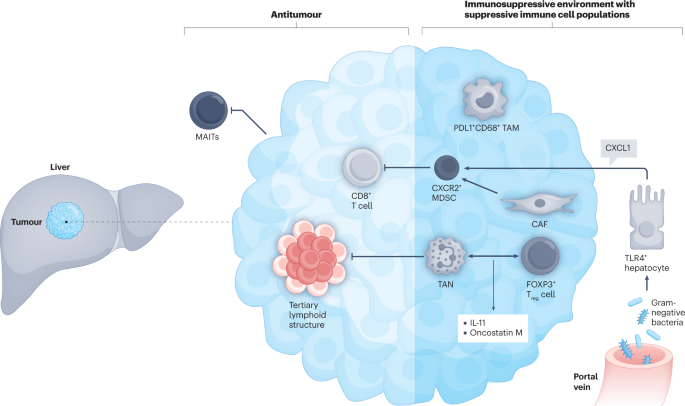

Immunotherapy

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are being used and investigated in cholangiocarcinoma, particularly in patients with MSI-H or high tumor mutational burden. Pembrolizumab and nivolumab are among the agents showing benefit in selected patients, and research continues into combination immunotherapy and new immune targets.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy can be used for patients with unresectable tumors, for palliation of symptoms, or after surgery in patients with high-risk features. Modern techniques such as stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) and proton therapy allow for precise targeting, minimizing damage to surrounding tissue. Radiation may also be used in combination with chemotherapy (chemoradiation) in select cases.

Locoregional Therapies

For patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma who are not candidates for surgery, locoregional therapies may provide tumor control or symptom relief:

- Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) delivers chemotherapy directly to the tumor via the hepatic artery.

- Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT), also called radioembolization, uses Y-90 microspheres.

- Ablative techniques such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or microwave ablation are suitable for small, localized tumors (Banales et al., Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020).

Biliary Drainage and Palliative Care

Biliary obstruction is a common and serious complication of cholangiocarcinoma. Endoscopic or percutaneous stenting relieves jaundice, improves liver function, and enhances quality of life. Palliative care—including pain management, nutritional support, and psychosocial support—is essential for patients with advanced disease.

2025 New Advances in Cholangiocarcinoma Treatment

The treatment landscape for cholangiocarcinoma continues to evolve rapidly, and several notable advances have emerged in 2025 that are reshaping patient care, especially for those with advanced or previously untreatable disease.

Expanded Targeted Therapy Options: In 2025, new data has confirmed the efficacy of additional FGFR inhibitors beyond pemigatinib and futibatinib for patients with FGFR2 fusion-positive intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Updated clinical trials have led to the approval of next-generation FGFR inhibitors with improved activity and safety profiles, offering more options for those with resistance to earlier agents.

Novel IDH Inhibitors: The field has seen the introduction of next-generation IDH1/2 inhibitors for IDH-mutant cholangiocarcinoma, showing enhanced activity and fewer side effects. These have become important alternatives for patients whose disease progresses on first-generation inhibitors.

Immunotherapy Breakthroughs: In 2025, several large studies have confirmed the benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors, especially for patients with high tumor mutational burden or MSI-high/mismatch repair-deficient tumors. New combination regimens pairing immunotherapy with chemotherapy or targeted therapy have shown improved response rates and survival in clinical trials, leading to updated treatment guidelines for select patients.

HER2 and BRAF Targeting: HER2-directed therapies (such as trastuzumab deruxtecan and tucatinib combinations) and BRAF/MEK inhibitor regimens are now recommended for patients with HER2-amplified or BRAF-mutated cholangiocarcinoma, based on new evidence from phase II and III studies.

Personalized Molecular Profiling as Standard: Routine comprehensive molecular profiling is now standard practice for all advanced cholangiocarcinoma cases, guiding the use of targeted therapy and immunotherapy. This approach ensures that patients can access the most effective, individualized treatments based on their tumor’s genetic alterations.

Locoregional and Ablative Innovations: Advances in interventional radiology, including new protocols for radioembolization (Y-90) and improved image-guided ablation techniques, have increased the safety and effectiveness of local therapies, even in patients with multifocal or borderline resectable tumors.

You Can Watch More on OncoDaily Youtube TV

Written by Armen Gevorgyan, MD

FAQ

What is cholangiocarcinoma?

Cholangiocarcinoma is a rare and aggressive cancer that develops in the bile ducts, which carry bile from the liver to the gallbladder and small intestine.

What are the main types of cholangiocarcinoma?

The three types are intrahepatic (within the liver), perihilar (at the bile duct junction), and distal (near the small intestine).

What are common symptoms of cholangiocarcinoma?

Symptoms include jaundice (yellowing of skin/eyes), itching, dark urine, pale stools, abdominal pain, weight loss, and fatigue.

Who is at risk for cholangiocarcinoma?

Risk factors include primary sclerosing cholangitis, liver fluke infection, chronic liver disease, bile duct abnormalities, and some genetic conditions.

How is cholangiocarcinoma diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves blood tests, imaging (ultrasound, CT, MRI/MRCP), tumor markers (CA 19-9), and tissue biopsy.

What are the current treatments for cholangiocarcinoma?

Treatment options include surgery, chemotherapy (gemcitabine/cisplatin), targeted therapy, immunotherapy, radiation, and palliative care.

What are the new advances in treatment as of 2025?

New advances include FGFR and IDH1 inhibitors, HER2-targeted drugs, expanded use of immunotherapy, and more personalized, biomarker-driven care.

Can cholangiocarcinoma be cured?

Surgical removal is the only potential cure, but most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage; new therapies are improving survival for some.

Should every patient have molecular profiling?

Yes, molecular profiling is now recommended for all advanced cases to identify targeted therapy options and clinical trial eligibility.

Are there clinical trials available for cholangiocarcinoma?

Yes, there are many ongoing clinical trials testing new drugs and combinations. Patients are encouraged to discuss trial options with their oncologist.