Small Cell Lung Cancer: Symptoms, Causes, Types, Diagnosis and Treatment

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is a highly aggressive subtype of lung cancer that originates from neuroendocrine cells. Representing about 15% of all lung cancers, SCLC is characterized by rapid growth, early dissemination, and strong association with tobacco smoking (Travis et al., 2015). Due to its aggressive nature and early metastasis, SCLC typically presents at an advanced stage, complicating treatment and prognosis (Kalemkerian et al., 2013).

You Can Read More About Neuroendocrine Lung Tumors on Oncodaily

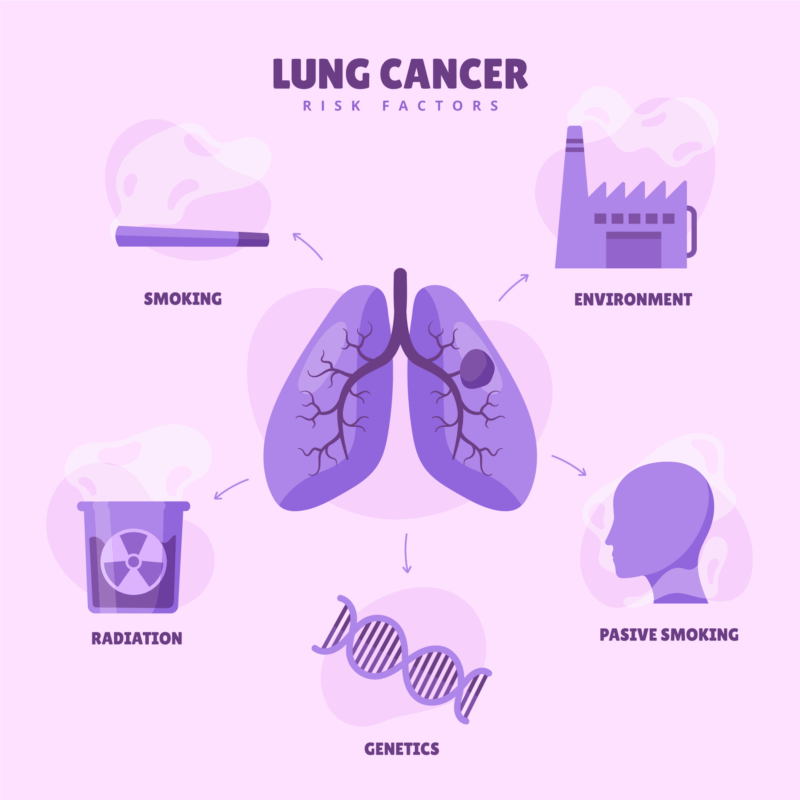

Causes and Risk Factors of Small Cell Lung Cancer

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is most strongly linked to cigarette smoking. More than 95% of individuals diagnosed with SCLC have a history of tobacco use, making it one of the most smoking-related malignancies (Kalemkerian et al., 2013). The carcinogens in tobacco smoke cause genetic mutations in pulmonary neuroendocrine cells, leading to malignant transformation.

In addition to active smoking, secondhand smoke exposure also elevates the risk, particularly in individuals with long-term exposure in enclosed environments (Govindan et al., 2006).

Environmental and occupational exposures also play a role. Substances such as radon gas, asbestos, uranium, and industrial chemicals like arsenic and chromium are recognized as lung carcinogens and may contribute to SCLC development (Gazdar et al., 2017).There is also increasing recognition of genetic susceptibility in a subset of patients. Individuals with a family history of lung cancer or genetic polymorphisms affecting DNA repair pathways may be at greater risk (Sequist & Lynch, 2012).

Moreover, the risk of SCLC is significantly lower in nonsmokers, suggesting a distinct etiological pathway compared to other lung cancers like adenocarcinoma, which is more common in non-smokers.

Classification of Small Cell Lung Cancer

Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC) is a high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma that is characterized by its aggressive behavior, rapid growth, and early metastasis. The classification of SCLC is typically based on histology, molecular features, and clinical staging. Understanding these classifications is vital for treatment decisions and predicting prognosis.

Histological Classification

Small Cell Lung Cancer is primarily classified based on its histological features, which show characteristic cell morphology under the microscope.

- Classic Small Cell Carcinoma (SCLC):This is the most common form of SCLC, characterized by small cells with scant cytoplasm, finely granular nuclear chromatin, absent or inconspicuous nucleoli, and high mitotic rates. These tumors have a very aggressive clinical course and are highly sensitive to chemotherapy but often relapse quickly (Travis et al., 2015).

- Combined Small Cell Carcinoma: A mixture of small cell carcinoma with other histological components such as squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or large cell carcinoma. This combined type often has a more heterogeneous clinical behavior and requires more complex treatment strategies.

- Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma (LCNEC): A subtype of SCLC that has a more aggressive clinical course. It features larger cells with abundant cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli but still shares neuroendocrine markers (Rudin et al., 2019).

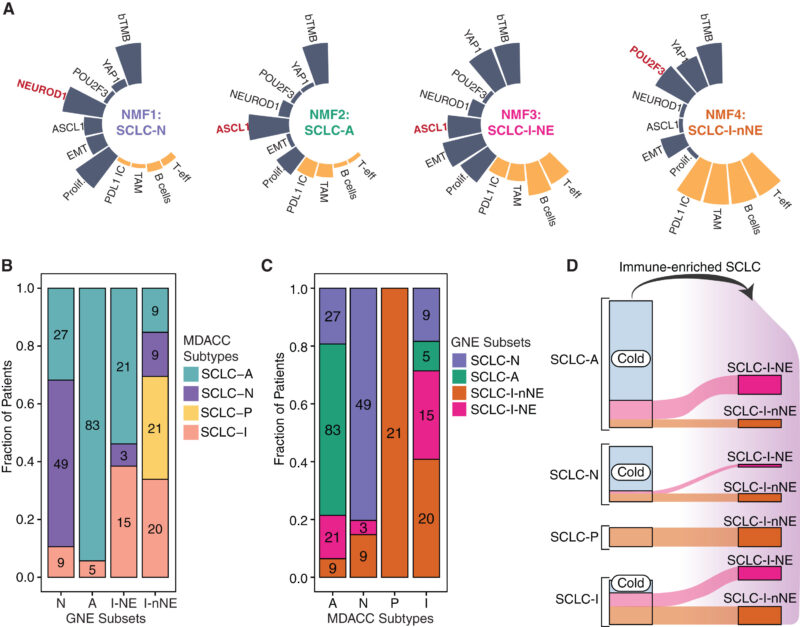

Molecular Classification

Recent research into the molecular characteristics of SCLC has led to the development of a more precise molecular classification system. This allows for a better understanding of the tumor’s biology and its response to treatment:

ASCL1-High (SCLC-A): ASCL1 (Achaete-Scute Homolog 1) is a transcription factor critical to neuroendocrine differentiation. The SCLC-A subtype shows high expression of ASCL1 and is responsive to conventional chemotherapy. These tumors are also associated with classic neuroendocrine morphology (George et al., 2015).

NEUROD1-High (SCLC-N): Characterized by high expression of NEUROD1, a factor linked to neurogenic differentiation, SCLC-N is associated with more aggressive disease and poorer prognosis. It has lower sensitivity to traditional therapies like platinum-based chemotherapy (George et al., 2015).

POU2F3-High (SCLC-P): This subtype expresses high levels of POU2F3, a transcription factor associated with tuft cell differentiation. These tumors may lack typical neuroendocrine features and might require alternative treatment strategies (Rudin et al., 2019).

Inflamed or YAP1-High (SCLC-I):Tumors in this category show high levels of immune infiltration and expression of YAP1, an oncogene involved in the regulation of tumor progression. These tumors may be more responsive to immunotherapy due to their immune-active microenvironment (Gay et al., 2021).

Clinical Staging

Staging for SCLC is usually determined by the TNM system (tumor size, lymph node involvement, and metastasis), but due to the rapid progression and early metastasis of SCLC, the disease is more often classified into two clinical stages:

- Limited-Stage SCLC (LS-SCLC):This stage is characterized by cancer that is confined to one side of the chest, including the lung, regional lymph nodes, and mediastinum. It is considered treatable with surgery or chemoradiation (Kalemkerian et al., 2013).

- Extensive-Stage SCLC (ES-SCLC):This stage describes cancer that has spread beyond one side of the chest to distant sites such as the liver, bones, or brain. This stage is typically not amenable to surgery and requires systemic treatment with chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy (Kalemkerian et al., 2013).

WHO Classification

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies SCLC based on the tumor’s neuroendocrine differentiation, morphology, and clinical behavior. SCLC is categorized under neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), alongside typical and atypical carcinoids, and other neuroendocrine malignancies. The WHO classifies SCLC as a high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma characterized by its aggressive nature, high mitotic rate, and neuroendocrine markers such as synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and CD56 (Travis et al., 2015).

Symptoms of Small Cell Lung Cancer

Small cell lung cancer tends to progress rapidly, leading to early symptoms that may resemble other respiratory conditions. Key signs and symptoms include:

- Persistent cough and chest pain: Often the first noticeable symptoms due to tumor growth in central airways.

- Shortness of breath and wheezing: Caused by obstruction or compression of the bronchi.

- Hemoptysis (coughing up blood): A critical sign that often leads to diagnostic imaging.

- Unexplained weight loss and fatigue: Common systemic effects of cancer progression.

- Hoarseness: Resulting from vocal cord nerve involvement.

- Swelling in the face or neck: Indicative of superior vena cava syndrome from mediastinal tumor pressure.

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is frequently associated with several paraneoplastic syndromes due to its neuroendocrine nature. One common syndrome is SIADH (syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion), which leads to hyponatremia by causing the kidneys to retain water. Another is Cushing’s syndrome, resulting from ectopic production of ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) by the tumor, leading to symptoms such as weight gain, hypertension, and glucose intolerance. Additionally, SCLC can cause Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome, an autoimmune disorder characterized by muscle weakness, particularly in the lower limbs, due to impaired neuromuscular transmission.

Prognosis of Small Cell Lung Cancer

The prognosis of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) remains poor due to its aggressive clinical behavior, rapid proliferation, and tendency for early metastasis. At the time of diagnosis, the majority of patients present with extensive-stage disease, which significantly limits curative treatment options.

For patients with limited-stage SCLC, the median survival ranges from 15 to 20 months with combined chemoradiation therapy, and the 5-year survival rate is approximately 20%–30% (Kalemkerian et al., 2013). In contrast, for extensive-stage SCLC, median survival is typically 8 to 13 months even with treatment, and the 5-year survival drops below 5% (Govindan et al., 2006).

Several prognostic factors influence outcomes, including stage at diagnosis, patient performance status, response to first-line therapy, and the presence of paraneoplastic syndromes or central nervous system involvement. Although SCLC initially responds well to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, most cases relapse within months, and recurrent disease often shows resistance to further treatment, contributing to the dismal long-term survival rates (Horn & Mansfield, 2018).

Diagnosis of Small Cell Lung Cancer

The diagnosis of Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC) requires a comprehensive, stepwise approach that integrates clinical evaluation, imaging, tissue sampling, and laboratory studies. Due to the aggressive nature of SCLC and its tendency for early metastasis, prompt and accurate diagnosis is critical for optimal treatment planning.

Clinical Evaluation: Diagnosis begins with a detailed history and physical examination. Patients often present with respiratory symptoms such as persistent cough, chest pain, dyspnea, hemoptysis, and signs of systemic illness including weight loss and fatigue. Special attention is given to smoking history, as over 95% of SCLC cases are associated with tobacco use. Paraneoplastic syndromes, such as SIADH or Cushing’s syndrome, may also guide clinical suspicion.

Imaging Techniques: Initial imaging includes a chest X-ray to detect a mass or atelectasis. A contrast-enhanced chest CT scan is essential to delineate tumor size, location, lymphadenopathy, and possible mediastinal involvement. For staging, PET-CT scans are used to identify metastatic disease. Brain MRI is recommended, especially in extensive-stage SCLC, due to the high risk of brain metastases.

Histopathological Confirmation: Definitive diagnosis requires tissue biopsy. For centrally located tumors, bronchoscopy with endobronchial biopsy is often used. CT-guided transthoracic needle aspiration may be performed for peripheral lesions. The biopsy is then examined microscopically. SCLC is characterized by small cells with scant cytoplasm, nuclear molding, finely granular chromatin, and a high mitotic index. Tumor cells typically express neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and CD56. Thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) is often positive and supports diagnosis, especially in small biopsies. These markers help distinguish SCLC from other neuroendocrine tumors and poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinomas.

Laboratory and Molecular Studies: Routine labs may show hyponatremia (in SIADH) or hyperglycemia (in ectopic Cushing’s syndrome). Although not used for diagnosis, biomarkers like neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and pro-gastrin-releasing peptide (ProGRP) may assist in monitoring response to treatment. Emerging molecular profiling may reveal subtypes (e.g., ASCL1, NEUROD1, POU2F3) that have implications for future targeted therapies.

Treatment Options for Small Cell Lung Cancer

Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive malignancy that requires prompt and comprehensive treatment. The choice of therapy depends on the stage of the disease, patient’s overall health, and specific tumor characteristics.

Surgical Management in Small Cell Lung Cancer

Surgical intervention in Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC) has a highly selective role, largely limited to patients with very early-stage disease. This restriction is due to the tumor’s aggressive nature, characterized by rapid growth and early dissemination (Kalemkerian et al., 2013).

Surgery is typically reserved for patients with clinical stage I SCLC (T1-2N0M0), where the tumor is localized and there is no evidence of lymph node involvement or distant metastasis. Before surgery is considered, mediastinal staging—often via mediastinoscopy or endobronchial ultrasound—is essential to confirm N0 status (Schreiber et al., 2010). When surgery is indicated, lobectomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection is the standard approach, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy to reduce the risk of systemic relapse (Kalemkerian et al., 2013).

In well-selected patients with early-stage disease, surgery can significantly improve outcomes. Studies have shown that 5-year survival rates may exceed 50% when surgery is followed by chemotherapy (Schreiber et al., 2010). These outcomes are comparable or superior to those achieved with chemoradiation in the same population, underscoring the importance of accurate staging and multidisciplinary evaluation.

Despite these potential benefits, surgery is not widely applicable. The vast majority of SCLC patients present with advanced disease, where systemic therapy is the cornerstone of treatment. Additionally, occult metastases and micrometastatic disease are often present at diagnosis, even in early-stage SCLC, making surgery alone insufficient (Rudin et al., 2019). Thus, its role is highly restricted and should only be pursued in specialized settings with experienced thoracic oncology teams.

Chemotherapy in Small Cell Lung Cancer

Chemotherapy remains the cornerstone of treatment for small cell lung cancer (SCLC) due to its aggressive nature and high initial response rates. This applies to both limited-stage and extensive-stage disease. Small cell lung cancer is characterized by rapid growth and early spread, which makes systemic chemotherapy essential even in localized stages (Kalemkerian et al., 2013).

In limited-stage SCLC, the standard of care involves a combination of chemotherapy and thoracic radiotherapy. The most commonly used regimen is cisplatin or carboplatin combined with etoposide. This combination, particularly when administered concurrently with radiation therapy, has been shown to improve overall survival and local tumor control (Turrisi et al., 1999).

For extensive-stage SCLC, chemotherapy remains the primary treatment. The combination of a platinum agent (cisplatin or carboplatin) with etoposide is also used in this setting. Recent advancements have introduced immunotherapy agents such as atezolizumab and durvalumab into the first-line treatment. These immune checkpoint inhibitors, when added to platinum-etoposide chemotherapy, have demonstrated improvements in overall survival and progression-free survival, leading to a new standard of care (Horn et al., 2018; Paz-Ares et al., 2019).

In the setting of relapsed or progressive SCLC, treatment decisions depend on the duration of the initial response. Patients who relapse within three months of completing initial chemotherapy are classified as platinum-refractory and have limited treatment options, often receiving topotecan or supportive care. Those who relapse after three months may be retreated with the initial regimen or offered alternative second-line therapies. Newer agents and clinical trials are exploring additional therapeutic options to improve outcomes in this challenging setting (Owonikoko et al., 2012).

Radiotherapy in Small Cell Lung Cancer

Radiotherapy (RT) remains a foundational treatment modality in the management of SCLC, particularly due to the tumor’s high radiosensitivity. It plays a pivotal role in both curative-intent regimens for limited-stage SCLC (LS-SCLC) and in palliative or consolidative approaches for extensive-stage SCLC (ES-SCLC).

Read more about Radiotherapy for Lung Cancer on Oncodaily

Thoracic Radiotherapy

For LS-SCLC, concurrent chemoradiotherapy is the standard approach, typically initiated early—within the first two cycles of chemotherapy. Hyperfractionated radiotherapy, delivered twice daily (1.5 Gy per fraction), has demonstrated superior survival outcomes compared to once-daily regimens. TRT is effective in improving local control and overall survival in LS-SCLC, with studies like the Intergroup 0096 trial showing a median survival of 23 months and a 5-year survival rate of approximately 26% with this strategy (Turrisi et al., 1999; NCCN, 2024).

In ES-SCLC, consolidative thoracic RT is considered for patients who exhibit a good response to initial chemotherapy. The CREST trial showed that consolidative TRT reduced intrathoracic recurrences and offered a modest survival benefit, especially in patients with residual thoracic disease post-chemotherapy (Slotman et al., 2015).

Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation

Given the high incidence of brain metastases in SCLC—up to 60% within two years—PCI is recommended for patients with LS-SCLC who respond to initial therapy. It significantly decreases the risk of symptomatic brain metastases and improves survival (Auperin et al., 1999). However, in ES-SCLC, the utility of PCI is controversial. A Japanese randomized trial found no overall survival benefit and suggested that MRI surveillance with brain-directed treatment upon relapse could be a safer alternative (Takahashi et al., 2017). Current NCCN guidelines suggest individualized decision-making based on performance status and neurocognitive considerations.

Whole Brain Radiotherapy and Stereotactic Radiosurgery

WBRT remains the mainstay for treating multiple brain metastases in SCLC due to the tumor’s diffuse dissemination. For patients with limited brain lesions and good performance status, SRS is being explored, although WBRT is generally preferred due to the higher risk of microscopic disease elsewhere in the brain (NCCN, 2024). Recent research is also evaluating hippocampal-sparing WBRT and memantine use to reduce cognitive decline associated with cranial irradiation, showing promising results in maintaining quality of life without compromising oncologic outcomes (Gondi et al., 2014).

Immunotherapy in Small Cell Lung Cancer

Immunotherapy has significantly reshaped the treatment landscape for Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC), particularly in patients with extensive-stage disease. Traditional treatments such as chemotherapy have shown high initial response rates but are frequently followed by relapse. As a result, immune checkpoint inhibitors have been introduced to enhance long-term outcomes.

Read More About Immunotherapy for Lung Cancer in OncoDaily

Extensive-Stage SCLC

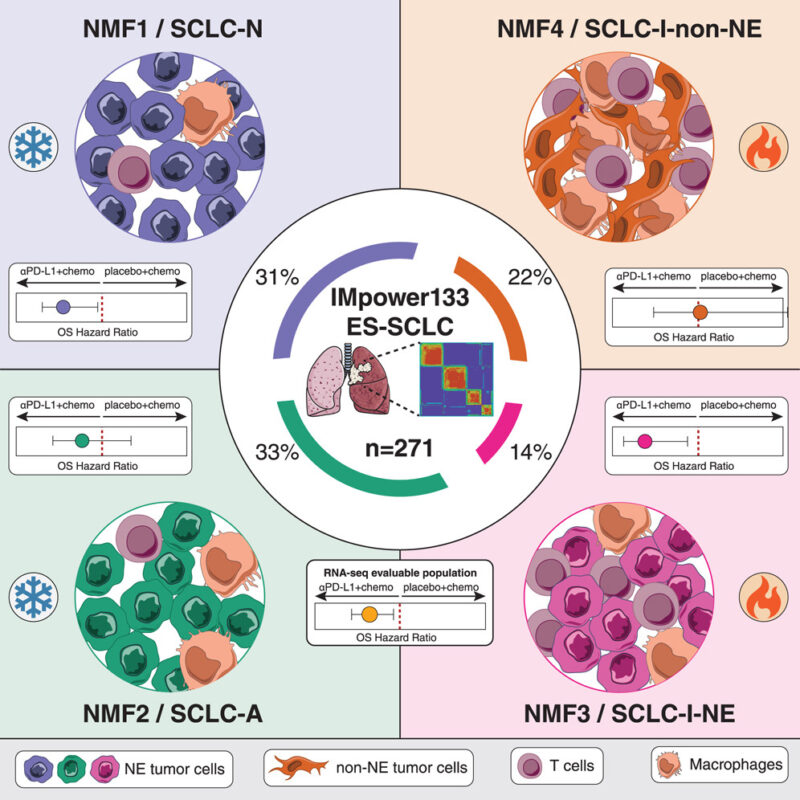

The most notable advances have been in the treatment of extensive-stage SCLC. The combination of atezolizumab (an anti–PD-L1 antibody) with platinum-based chemotherapy and etoposide has been shown to improve overall survival compared to chemotherapy alone. This combination became a standard first-line therapy after the IMpower133 trial. Similarly, the CASPIAN trial established durvalumab as another effective PD-L1 inhibitor when combined with chemotherapy. These therapies work by blocking PD-L1, a protein used by cancer cells to evade immune detection, thereby allowing the immune system to recognize and attack tumor cells (Horn et al., 2018; Paz-Ares et al., 2019).

Limited-Stage SCLC

In limited-stage SCLC, the role of immunotherapy is still being defined. Some trials have tested maintenance immunotherapy after concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Although promising, more data is needed before immunotherapy becomes routine in this setting. Early studies with durvalumab and atezolizumab as maintenance therapy show favorable trends in progression-free survival (Rudin et al., 2021).

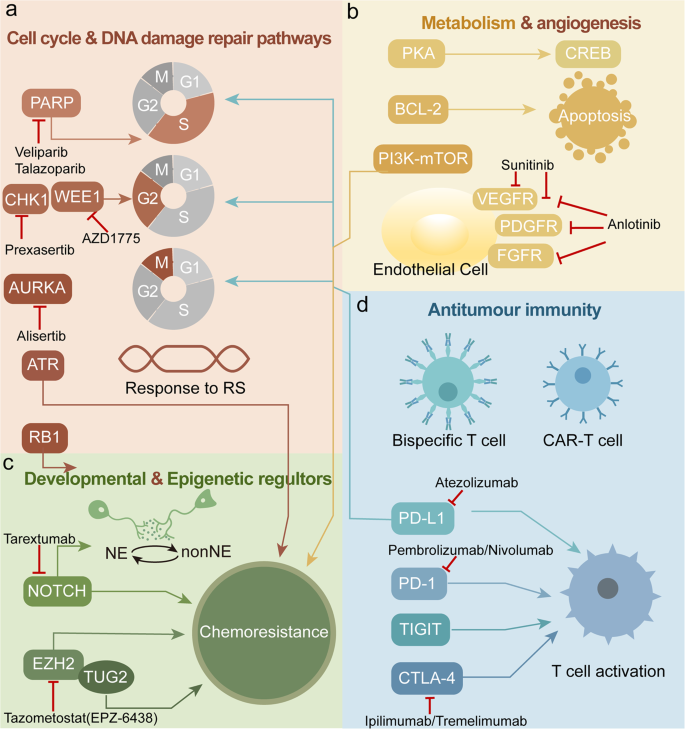

Emerging Therapies and Clinical Trials in Small Cell Lung Cancer

As treatment for SCLC continues to evolve, new therapies and clinical trials are aiming to address the aggressive nature and poor long-term outcomes associated with the disease.

Immunotherapy Innovations

Immunotherapy has become a cornerstone of first-line treatment in extensive-stage SCLC. Notably, the addition of immune checkpoint inhibitors to chemotherapy has extended survival outcomes.

For example, the CASPIAN trial demonstrated that adding durvalumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, to standard platinum-etoposide chemotherapy significantly improved overall survival compared to chemotherapy alone (Paz-Ares et al., 2019). Similarly, the IMpower133 trial found that combining atezolizumab with chemotherapy improved both progression-free and overall survival (Horn et al., 2018).

Oncolytic Virus Therapy and Immunomodulation

A Phase I clinical trial is exploring the combination of oncolytic virus injections with checkpoint inhibitors (nivolumab and ipilimumab) in high-grade neuroendocrine tumors, including SCLC. Early data suggest this approach could convert immunologically “cold” tumors into “hot” tumors that are more responsive to immunotherapy (Chauhan et al., 2025).

DLL3-Targeted Therapy

Tarlatamab, a bispecific T-cell engager targeting DLL3 (commonly expressed in SCLC) and CD3, is undergoing evaluation in multiple trials. In the phase II DeLLphi-301 trial, it showed an objective response rate of 40%, with a median progression-free survival of 4.9 months and overall survival of 14.3 months in patients with extensive-stage SCLC who had relapsed after chemotherapy (Lee et al., 2024).

You Can Read More about Tarlatamab on OncoDaily

PARP Inhibition Trials

Another innovative strategy involves combining PARP inhibitors with chemotherapy. A Phase II trial is currently assessing talazoparib plus low-dose temozolomide in relapsed extensive-stage SCLC. This regimen aims to exploit DNA repair deficiencies in tumor cells, and preliminary results show a response rate of nearly 40% (Goldman et al., 2022).

Tyrosine Kinase and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Combinations

Ongoing trials are also examining combinations like cabozantinib (a multi-kinase inhibitor) with nivolumab and ipilimumab. These regimens aim to suppress tumor angiogenesis and improve T-cell infiltration and activation. Early findings suggest promising response rates in poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors, including SCLC (Smith et al., 2023).

GSPT1 Degraders for MYC-Amplified SCLC

MRT-2359, a molecular glue degrader of GSPT1, is being evaluated in SCLC patients with MYC gene amplification. This novel therapy disrupts oncogenic translation and has shown early efficacy signals in preclinical models and early-phase trials (UCSD Clinical Trials, 2025).

You Can Watch More on OncoDaily Youtube TV

Written by Armen Gevorgyan, MD

FAQ

What is Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC)?

Small Cell Lung Cancer is a highly aggressive form of lung cancer originating from neuroendocrine cells. It accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers and is strongly associated with tobacco smoking.

What are the primary causes and risk factors for SCLC?

The predominant risk factor is cigarette smoking, including exposure to secondhand smoke. Other factors include exposure to carcinogens like radon gas, asbestos, uranium, and certain industrial chemicals. Genetic predispositions and family history may also play a role.

How is SCLC classified?

SCLC is classified histologically into classic and variant forms, including combined small cell carcinoma. Molecular classifications identify subtypes based on gene expression, such as ASCL1-high (SCLC-A), NEUROD1-high (SCLC-N), POU2F3-high (SCLC-P), and YAP1-high (SCLC-I).

What are common symptoms of SCLC?

Symptoms often include persistent cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, wheezing, hemoptysis (coughing up blood), unexplained weight loss, fatigue, hoarseness, and swelling in the face or neck.Paraneoplastic syndromes like SIADH and Cushing’s syndrome may also be present.

How is SCLC diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves a combination of medical history, physical examination, imaging studies (such as chest X-rays and CT scans), and tissue sampling through biopsies. Immunohistochemistry helps confirm the diagnosis by identifying specific neuroendocrine markers.

What are the stages of SCLC?

SCLC is typically staged into two categories: Limited-Stage (LS-SCLC), where cancer is confined to one side of the chest, and Extensive-Stage (ES-SCLC), where cancer has spread beyond one side of the chest or to distant organs.

What treatment options are available for SCLC?

Treatment depends on the stage and may include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and in select cases, surgery. For LS-SCLC, concurrent chemoradiotherapy is standard, while ES-SCLC often involves chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy agents.

What is the prognosis for SCLC patients?

Prognosis varies by stage. LS-SCLC has a median survival of 15 to 20 months with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 20%–30%. ES-SCLC has a median survival of 8 to 13 months, with a 5-year survival rate below 5%.

Are there emerging therapies and clinical trials for SCLC?

Yes, ongoing research includes immunotherapy innovations, oncolytic virus therapy, DLL3-targeted therapies like tarlatamab, PARP inhibitors combined with chemotherapy, and novel agents targeting specific molecular pathways.

Can SCLC be prevented?

While not all cases are preventable, the most effective prevention strategy is avoiding tobacco use. Reducing exposure to known carcinogens and regular health check-ups can also aid in early detection and prevention.

-

Challenging the Status Quo in Colorectal Cancer 2024

December 6-8, 2024

-

ESMO 2024 Congress

September 13-17, 2024

-

ASCO Annual Meeting

May 30 - June 4, 2024

-

Yvonne Award 2024

May 31, 2024

-

OncoThon 2024, Online

Feb. 15, 2024

-

Global Summit on War & Cancer 2023, Online

Dec. 14-16, 2023