January’s Cervical Cancer Awareness Month underscores a hard truth: cervical cancer is largely preventable, yet it still kills at scale. In 2022, an estimated 660,000 women were diagnosed worldwide and about 350,000 died (WHO 2025) making cervical cancer the fourth most common cancer in women globally. Nearly all cases are driven by persistent infection with high‑risk HPV, but the burden is profoundly unequal: around 94% of deaths occur in low‑ and middle‑income countries, and in 37 countries cervical cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death among women (McDowell, 2024).

Elimination is no longer a slogan, it’s a blueprint. The WHO 90–70–90 targets rely on scaling high‑performance screening (screening 70% of women by 35 and again by 45), alongside vaccination and timely treatment. That pressure is accelerating a fundamental change in screening: a shift from morphology to etiology. Pap cytology transformed prevention, but high‑risk HPV testing is now driving higher sensitivity and reshaping screening intervals, triage pathways, and program design. Self‑sampling may be the access breakthrough, especially where clinic‑based screening underperforms. Yet none of these gains hold without rigorous quality systems: controls, standardized materials, and training tools that keep results reproducible across labs and settings.

Two breakthroughs define modern cervical cancer prevention: Pap cytology, which made population screening possible, and HPV biology, which clarified what screening should target. The move from one to the other explains today’s guideline changes and the push for wider access.

From Pap Cytology to Primary HPV Testing: An Evolution in Screening

The Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, introduced in the 1940s, was the first widely adopted test to detect cervical precancer and cancer. Its implementation led to dramatic declines in cervical cancer rates, mortality in the U.S. dropped by over 70% from the 1950s to 1990s thanks to regular Pap screening (Wingo et al., 2003). The Pap test involves collecting cervical cells and having a cytopathologist examine them for abnormalities. This method, largely unchanged for decades, proved effective in developed countries but required substantial laboratory infrastructure and repeated frequent screening to compensate for its moderate sensitivity.

By the 1980s, research uncovered that human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the cause of the vast majority of cervical cancers. This paradigm shift paved the way for new preventive tools, notably the HPV vaccine (introduced in 2006) and, later, molecular tests to detect HPV DNA in cervical samples. In 2014 the first HPV test was FDA-approved for primary cervical cancer screening, and by 2020 organizations like the American Cancer Society had endorsed primary HPV testing (HPV testing alone) as the preferred screening method. Countries such as Australia, the Netherlands, and the UK were early adopters of the HPV-first model, replacing or augmenting Pap cytology in their national programs (Delpero & Selk, 2022).

You Can Read More About HPV on OncoDaily.

Pap vs. HPV Test: The fundamental difference lies in what each test detects. Pap smears identify abnormal cervical cells under a microscope, whereas HPV tests use techniques like PCR to detect high-risk HPV DNA in a sample . HPV presence is a prerequisite for cervical cancer , so testing directly for the virus can catch infection and risk earlier than cytology, which requires cellular changes to be visible. As cervical cancer precursors become less common due to vaccination, a highly sensitive test is needed to continue catching cases, a key reason health systems have sought the switch to HPV testing.

You Can Also Read Cervical Cancer Screening: Who Needs a Pap Smear or HPV Test and When? by OncoDaily.

Clinical Advantages of HPV Testing: Sensitivity, NPV, and Risk Stratification

HPV testing offers significant clinical advantages over Pap cytology in terms of sensitivity and risk prediction. Studies show that HPV DNA testing is far more sensitive than the Pap smear for detecting high-grade cervical lesions. A Canadian analysis reported HPV testing has about 94.6% sensitivity for precancerous lesions, compared to only 55.4% for cytology (Mayrand et al., 2007).

In other words, Pap smears can miss nearly half of existing cervical precancers, whereas HPV tests catch the vast majority. This superior sensitivity translates into earlier detection of lesions that Pap-based screening might overlook, as confirmed by randomized trials. In the FOCAL trial in British Columbia, women screened with primary HPV had significantly fewer high-grade lesions on exit testing than women screened with Pap, implying many lesions were missed in the cytology group (Ogilvie et al., 2018).

The negative predictive value (NPV) of HPV testing is exceptionally high, which has important implications for patient reassurance and screening intervals. A negative high-risk HPV test confers a >99% NPV for high-grade disease in the near future (Luckett et al., 2019). Long-term follow-up data indicate that the chance of developing CIN3 or cancer within 10 years after a single negative HPV test is under 1% (Inturrisi et al., 2022).

This strong NPV allows clinicians to safely extend screening intervals to 5 years or more with primary HPV screening, reducing patient burden without compromising safety. By contrast, the Pap test’s lower sensitivity necessitated shorter intervals (typically 2–3 years) to ensure lesions missed on one round could be caught on the next (Wheeler, 2019). A negative HPV result is thus a much more reassuring indicator of low risk than a negative Pap, enabling risk-based stratification of who needs immediate follow-up.

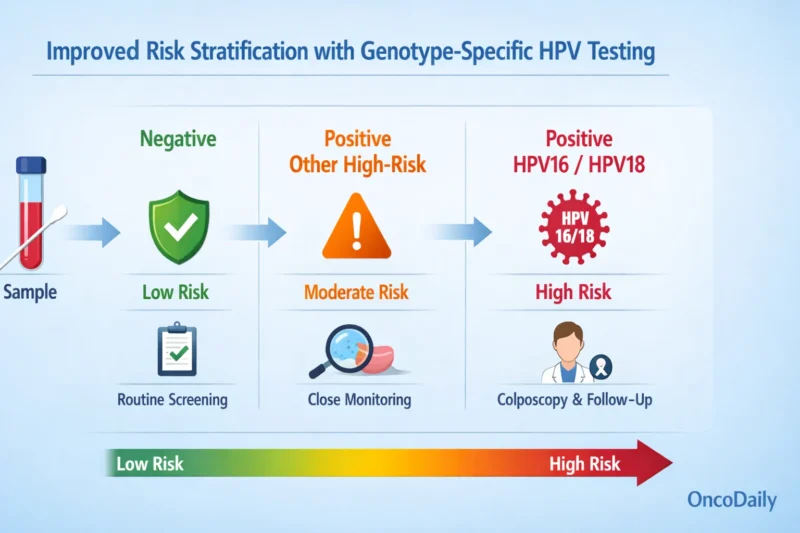

Another key advantage of HPV-based screening is improved risk stratification. HPV-based screening improves risk stratification by identifying high-risk genotypes (e.g., HPV16/18) and enabling tailored follow-up. Individuals positive for HPV16/18 can be referred directly to colposcopy, while those with other high-risk types may undergo reflex cytology or repeat testing at 12 months.

As HPV vaccination becomes more widespread, particularly against HPV16/18, the relative contribution of other high-risk HPV types is increasing, driving a shift toward broader HPV genotyping to further refine individual risk. This evolving approach supports more personalized care, targets intervention to those most likely to develop cancer, and more accurately identifies the population from which nearly all cervical cancers arise.

In contrast, Pap cytology reflects only current cellular changes and poorly predicts future risk when normal. Incorporating HPV status into risk-based guidelines (e.g., ASCCP) allows estimation of 5- and 10-year cancer risk using test history. Fontham et al. (2020) showed primary HPV testing from age 25 prevents ~13% more cancers and 7% more deaths than cytology, with only modest increases in follow-up. Higher sensitivity and better risk stratification reduce false negatives and support longer screening intervals.

International Screening Guidelines: HPV Testing in Policy and Practice

HPV testing has moved from evidence to policy. The World Health Organization now recommends primary HPV testing as the foundation of cervical cancer screening and a central pillar of its Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative. By 2030, WHO targets screening 70% of women with an HPV test by ages 35 and 45. Current guidance supports starting at age 30 (25 for people with HIV), extending screening intervals to 5–10 years, and using screen-and-treat models that enable faster action, particularly in low-resource settings.

In the United States, national guidelines increasingly favor HPV-based approaches. The USPSTF allows three options for women aged 30–65, with primary HPV testing every five years preferred when available. The American Cancer Society went further in 2020, recommending HPV-first screening beginning at age 25, reflecting both the test’s higher sensitivity and declining cervical cancer incidence in younger, vaccinated populations. Together, these recommendations signal a clear shift away from cytology-only paradigms.

Europe is following a similar trajectory. European guidelines strongly endorse primary HPV screening, citing superior sensitivity, reproducibility, and the ability to safely lengthen screening intervals. Several countries, including the Netherlands, the UK, Italy, Sweden, and Finland, have implemented or are completing national rollouts (Maver & Poljak et al., 2019). Early adopters such as Australia and England report increased detection of high-grade precancer and are on track for substantial reductions in cervical cancer incidence (Hall et al., 2019).

Across regions, one message is consistent: coverage matters as much as technology. While some countries continue hybrid strategies due to cost or infrastructure constraints, the global direction is unmistakable. HPV testing is no longer emerging, it is now the backbone of cervical cancer screening policy worldwide.

Forward-Looking:

Self-Sampling for HPV to Reach Underserved Populations

Self-sampling for HPV testing is a key innovation in cervical screening. Women collect their own cervico-vaginal sample using a swab or brush, eliminating the need for a clinician-performed pelvic exam. This approach can substantially increase participation among women facing barriers such as limited access, cultural concerns, or mistrust of healthcare. Studies show high acceptability, with most women finding self-sampling easy and comfortable. Importantly, HPV testing on self-collected samples demonstrates equivalent sensitivity to clinician-collected samples for detecting high-grade lesions (CIN2+), with large trials confirming non-inferior performance and supporting regulatory approval of at-home collection devices (Waly et al., 2025; Fitzpatrick et al., 2025).

Beyond test performance, self-sampling changes how screening can be delivered. By removing the need for in-clinic pelvic exams, HPV screening becomes far less dependent on clinician availability, infrastructure, and geography. This is especially consequential in low- and middle-income countries, where limited healthcare access, not test accuracy, is the primary driver of low screening coverage. When paired with reliable triage and follow-up systems, self-collection enables population-level screening in settings where clinic-based programs have never been scalable, with the potential to substantially reduce cervical cancer incidence in regions that bear the highest global burden.

Ensuring Quality in the HPV Screening Era: Microbix’s Role in Standardized Controls

As cervical cancer screening evolves, maintaining high quality and consistency in testing is paramount. Laboratories around the world must ensure that HPV tests (and remaining cytology or biomarker tests used for triage) perform reliably and comparably. A stark reminder of what can happen when quality systems fail is Ireland’s CervicalCheck screening program, where retrospective audits revealed false-negative Pap test results in 221 women, contributing to delayed diagnoses and 20 deaths, as highlighted by Cullen (2018). The subsequent inquiry highlighted variability in test interpretation and gaps in system-wide quality assurance, demonstrating how the absence of robust, standardized controls can allow performance issues to go undetected across laboratories.

Specialized quality control (QC) materials are used in cervical and HPV screening programs to support assay validation, personnel training, routine QC, and external quality assessment (EQA). These materials are processed through the same diagnostic workflows as patient specimens and contain characterized targets that allow laboratories to verify analytical performance.

One example of a QC material provider is Microbix Biosystems, which produces inactivated HPV reference materials used by clinical laboratories. These materials include HPV target genes commonly assessed in molecular assays (such as E6, E7, L1, and E1) and human cellular material in a preservative matrix intended to approximate clinical samples. The materials cover multiple high-risk HPV genotypes, including types 16, 18, 31, 33, 39, 45, 51, 52, and 66, and are available in both liquid and swab formats corresponding to centralized laboratory testing and self-collection workflows.

The key value of these controls lies in their commutability. They are engineered to behave like real clinical samples across diverse HPV testing platforms and laboratory workflows. As a result, they are compatible with a wide range of nucleic acid amplification technologies, including both PCR- and TMA-based assays. Laboratories routinely use these external quality controls—commercially offered under product names such as REDx™ Controls—to benchmark assay performance, train laboratory personnel, and validate the end-to-end testing process from sample preparation and extraction through to result interpretation.

In addition, Microbix’s new product pipeline includes formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) slides with simulated tissue samples that are positive or negative for HPV. These standardized FFPE slides are designed to be processed exactly like patient biopsy specimens, including routine cytology and histology staining, with reflex triage to HPV DNA or RNA testing. This QC format is particularly relevant for workflows supporting the detection and characterization of HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC).

By using reproducible FFPE slides across multiple laboratories and assay platforms, facilities can standardize methodologies between sites, monitor inter-laboratory diagnostic performance, and ensure consistency and reproducibility of results. These materials are also highly valuable for EQA (proficiency testing) programs, in which laboratories test blinded samples from an independent provider to verify ongoing diagnostic accuracy. Microbix FFPE slides have already been deployed in pilot EQA studies in Europe, where results highlighted both the inherent subjectivity in current diagnostic practices, particularly in p16 immunohistochemistry interpretation, and the critical importance of robust quality management systems to support harmonized and reliable testing.

The role of Microbix and similar providers is to underpin the integrity of cervical screening as it modernizes. When health agencies mandate a new primary HPV test, each laboratory must validate that assay, often using third-party reference materials to simulate low positive, high positive, and negative cases. Standardized controls ensure that an HPV test can detect multiple HPV genotypes at the required sensitivity, even under varying conditions. They help labs avoid false negatives (by confirming the test picks up even low levels of HPV) and false positives (by checking specificity against HPV-negative samples that contain human DNA and other potential contaminants).

In the cytology realm, prepared slides with known abnormalities aid in training cytotechnologists and assessing their proficiency in identifying abnormal cells. All of this supports a high level of diagnostic reliability and comparability across laboratories and countries. Microbix contributes essential but behind-the-scenes components of cervical screening programs worldwide, standardized QC materials that enable labs to validate and maintain the accuracy of HPV assays and related tests. This, in turn, bolsters the overall effectiveness of screening programs by ensuring that test results (whether Pap or HPV) are trustworthy and reproducible, ultimately helping clinicians and patients rely on the screening process to deliver the promised public health benefits.

Where Cervical Cancer Screening Is Headed

The global shift from Pap cytology to HPV testing marks a new chapter in cervical cancer prevention. This evolution has been driven by robust evidence: HPV-based screening detects more disease, earlier, and provides greater long-term assurance with less frequent testing, crucial advantages as cervical cancer becomes rarer in vaccinated populations. International guidelines increasingly reflect this reality by recommending HPV testing as the preferred or primary modality for cervical cancer screening. Implementing these changes on a broad scale requires not only political will and education to overcome inertia, but also attention to practical challenges like maintaining quality and reaching those who remain unscreened.

Fortunately, the future of cervical screening looks bright. Forward-looking, innovations like self-sampling for HPV promise to reach underserved women and further democratize access to this life-saving test. Early adopters of self-collection are already seeing improved participation rates, and ongoing research is refining how to best integrate this option into screening programs. Meanwhile, the often-unsung work of quality assurance continues to ensure that every test result, Pap or HPV, is as accurate and meaningful as possible. By leveraging standardized quality control materials and rigorous training, labs around the world uphold the high standards that modern cervical screening demands .

As we recognize Cervical Cancer Awareness Month, the message for clinicians, public health professionals, and policy-makers is one of progress and optimism. The move from “Pap vs. HPV test” is not an either-or debate anymore, but rather a coordinated transition to smarter screening strategies that combine the best of science and implementation. With continued commitment to guidelines, innovation, and quality, the vision of dramatically reducing, and one day eliminating cervical cancer is within reach. HPV testing has proven to be a powerful tool in this effort, and together with vaccination and improved screening access, it is poised to save countless lives worldwide.

For a global, practice-oriented perspective on how cervical cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment are evolving, see Highlights from How I Treat Cervical Cancer in 2026, summarizing discussions from the OncoDaily Cervical Cancer Summit held during Cervical Cancer Awareness Month.

Written by: Semiramida Nina Markosyan, Editor, OncoDaily Canada