Olubukola Ayodele, Breast Cancer Lead at University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, shared a post on LinkedIn:

“I’ve seen a few recent posts suggesting that “screening doesn’t change the time of death” because of lead-time bias. It’s a catchy line, but it’s also misleading and risks feeding confusion at a time when screening uptake is already far from where it should be.

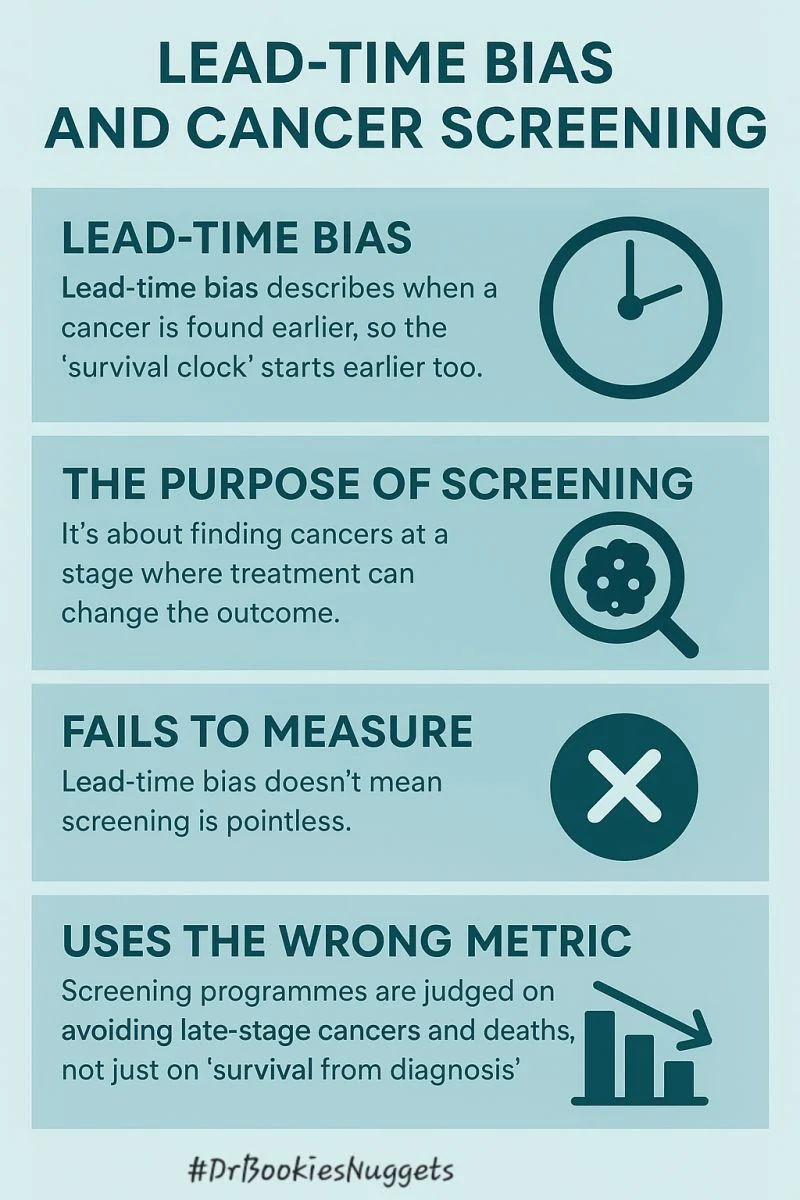

Lead-time bias is real, but it doesn’t mean screening is pointless.

Lead-time bias simply describes what happens when a cancer is found earlier, so the “survival clock” starts earlier too. If the cancer behaves exactly the same and treatment makes no difference, it can look as though someone lived longer just because the diagnosis happened sooner. That’s a limitation of the way survival statistics are measured, not of screening itself.

Lead-time bias is like setting your watch early. It makes it look like you’ve had more time, but it doesn’t change when the train actually leaves.

But screening isn’t about setting the watch early, it’s about giving you time to catch a different train altogether.

The purpose of screening is very different. It’s about finding cancers at a stage where treatment CAN change the outcome. Earlier detection often means less aggressive therapy, fewer complications and a better chance of cure. This is well-established in breast cancer and several other tumour types.

That’s why national screening programmes aren’t judged on “survival from diagnosis.” They’re judged on things that truly matter for patients: fewer late-stage cancers and fewer deaths at a population level. Those benefits have been shown repeatedly over decades.

So yes, we should teach lead-time bias, it helps us interpret data responsibly. But using it to imply that screening has no impact misses the point entirely. Worse, it risks undermining public confidence in programmes that save lives, especially in communities where uptake is already low and inequalities run deep.

If we’re going to talk about screening on public platforms, we need to do it with care. People deserve clear explanations, not simplified statements that strip away context. When misinformation spreads, it’s patients who pay the price.

Screening should be risk stratified rather a blanket approach which is what many national screening programmes have currently.

Screening isn’t perfect, but it remains one of the strongest tools we have for early detection. The conversation should be about improving access, addressing barriers and supporting people to make informed decisions, not discouraging participation based on misunderstood concepts.”

More posts featuring Olubukola Ayodele.