Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor: Symptoms, Causes, Types, Diagnosis and Treatment

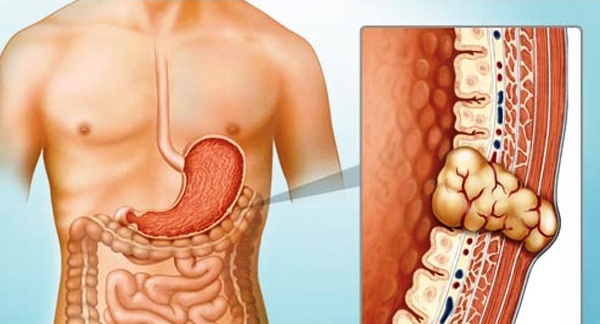

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are uncommon cancers that originate from specialized nerve cells located in the walls of the digestive system, known as interstitial cells of Cajal. These cells are part of the autonomic nervous system and regulate the movement of food through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. GIST can develop anywhere along the GI tract but are most frequently found in the stomach (approximately 60% of cases) and the small intestine (about 35%). (American Cancer Society)

The exact number of people diagnosed with GIST each year is not precisely known, but current estimates suggest that approximately 4,000 to 6,000 new cases occur annually in the United States. These tumors are most commonly diagnosed in individuals over the age of 50 and are rare in people younger than 40, though they can occur at any age. (American Cancer Society)

This article aims to provide an updated review of GISTs, focusing on their symptoms, causes, classification types, diagnostic approaches, and treatment options, incorporating contemporary research findings and clinical practices.

Symptoms and Causes

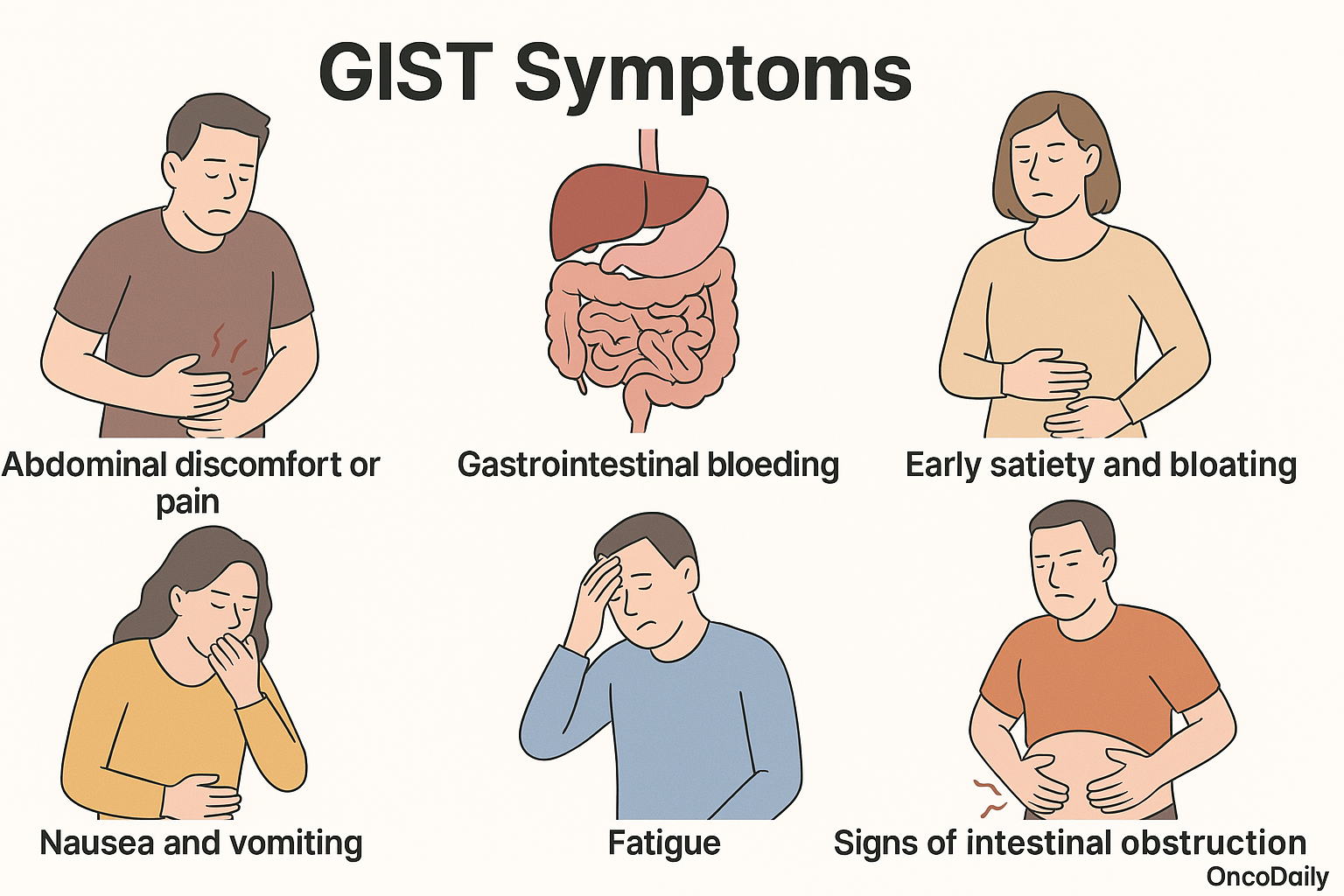

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) often present with non-specific and variable symptoms, making early diagnosis challenging. Many cases are asymptomatic and are detected incidentally during imaging, endoscopy, or surgery performed for unrelated reasons. When symptomatic, clinical presentation largely depends on the tumor size, anatomical location, and extent of growth. The most commonly reported symptoms include:

-

Abdominal discomfort or pain, often vague and persistent

-

Gastrointestinal bleeding, which may manifest as melena, hematemesis, or occult blood loss leading to iron-deficiency anemia

-

Early satiety and bloating, especially in gastric GISTs due to mass effect

-

Nausea, vomiting, and fatigue

-

Palpable abdominal mass, particularly in larger tumors

-

Signs of intestinal obstruction, such as severe pain, distension, and constipation, more frequently seen in small bowel GIST

The location of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor significantly shapes its clinical presentation. Gastric GIST, which are the most frequently encountered, may manifest through upper gastrointestinal bleeding, vague epigastric discomfort, or remain entirely asymptomatic—only to be discovered incidentally during procedures such as gastroscopy. In contrast, small intestinal GISTs tend to remain clinically silent for longer periods due to their deep anatomical location. However, when they do become symptomatic, they are more likely to present acutely with gastrointestinal hemorrhage or signs of intestinal obstruction. This is often attributed to the narrower lumen and limited compliance of the small intestine, which makes it more susceptible to the compressive effects of the tumor.

Colorectal and rectal GIST, although rare, may lead to symptoms such as tenesmus, rectal bleeding, or changes in bowel habits, depending on their size and position within the lower gastrointestinal tract. In advanced cases, tumor rupture or dissemination within the abdominal cavity can result in hemoperitoneum or peritoneal carcinomatosis, which typically presents as an acute abdomen requiring immediate medical attention. Given the broad and often subtle nature of symptoms—especially in the early stages—clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion, particularly in patients presenting with unexplained abdominal discomfort, gastrointestinal bleeding, or incidental abdominal masses. Prompt investigation and appropriate imaging are essential for timely diagnosis and management.

Etiology and Pathology

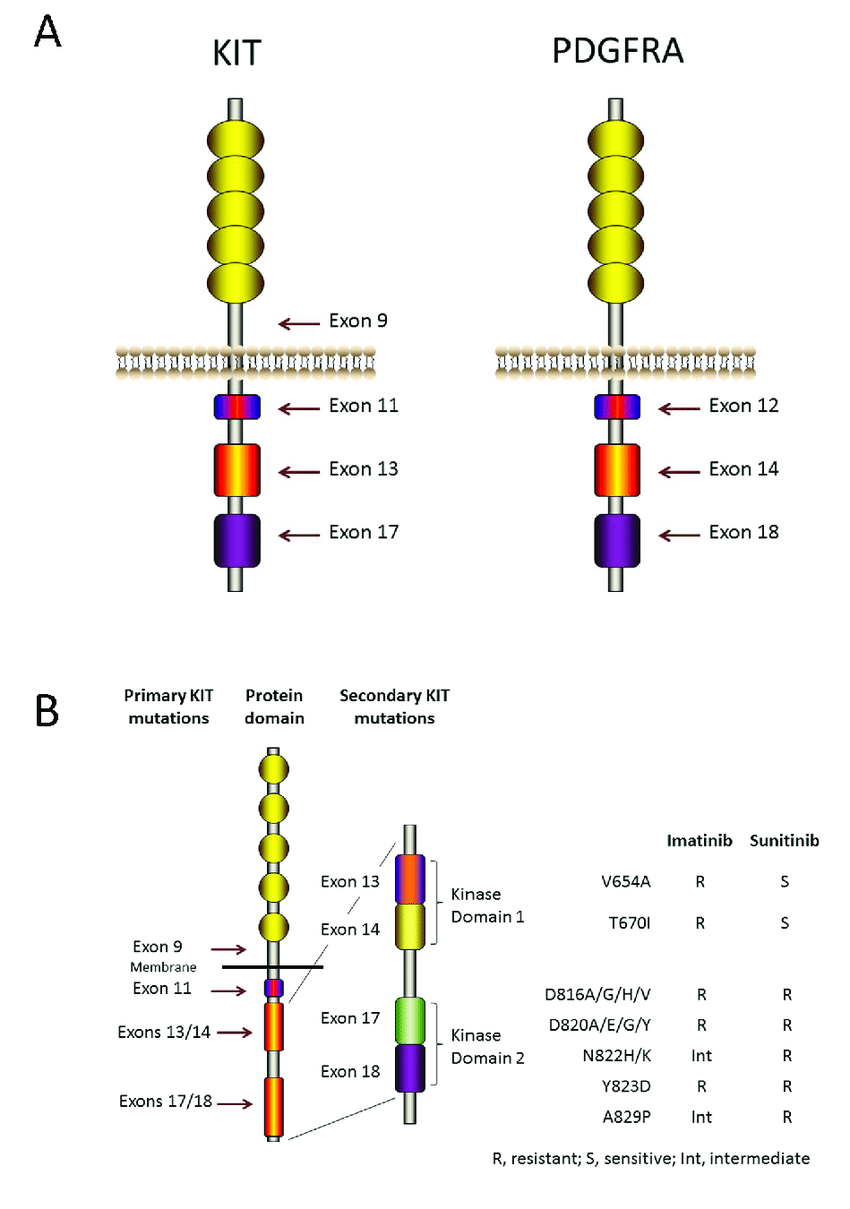

The pathogenesis of GIST is strongly associated with gain-of-function mutations in the KIT proto-oncogene, present in approximately 75–80% of cases, or mutations in platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA), found in around 5–10% of tumors. These mutations result in constitutive activation of tyrosine kinase receptors, leading to downstream signaling and uncontrolled cell proliferation. A subset of GIST lacks mutations in both KIT and PDGFRA and is referred to as wild-type (WT) GIST. These tumors may harbor alterations in other molecular pathways, including succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) complex deficiency, as well as mutations in BRAF, RAS, or neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase (NTRK) gene fusions. WT GISTs are more frequently observed in pediatric and young adult populations and demonstrate distinct biological and clinical behaviors, often requiring alternative diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. (American Cancer Society)

Hereditary syndromes associated with GISTs, though rare, include familial GIST syndromes (germline KIT/PDGFRA mutations), Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)—where multiple small bowel GIST may occur without KIT or PDGFRA mutations—and Carney-Stratakis syndrome, which involves germline mutations affecting SDH subunits. From a pathological standpoint, GISTs can exhibit spindle cell, epithelioid, or mixed morphology, with spindle cell being the most common. Histologically, they are typically low in pleomorphism but may vary significantly in mitotic activity, which is an essential parameter for risk stratification. Immunohistochemistry plays a pivotal role in the diagnosis of GISTs, as most tumors express KIT (CD117) and DOG1, which are highly sensitive and specific markers. CD34 is also commonly positive, while S100 and desmin are usually negative, aiding in the differential diagnosis from other soft tissue tumors such as leiomyomas or schwannomas.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) relies on a multidisciplinary approach combining clinical evaluation, advanced imaging, endoscopic assessment, histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and molecular analysis. Given the nonspecific nature of symptoms, which may include vague abdominal discomfort, early satiety, or occult bleeding, diagnosis is often delayed. In many cases, GISTs are discovered incidentally during imaging or surgical procedures performed for unrelated conditions. Therefore, clinical suspicion must remain high, particularly in patients with unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms or abdominal masses (American Cancer Society).

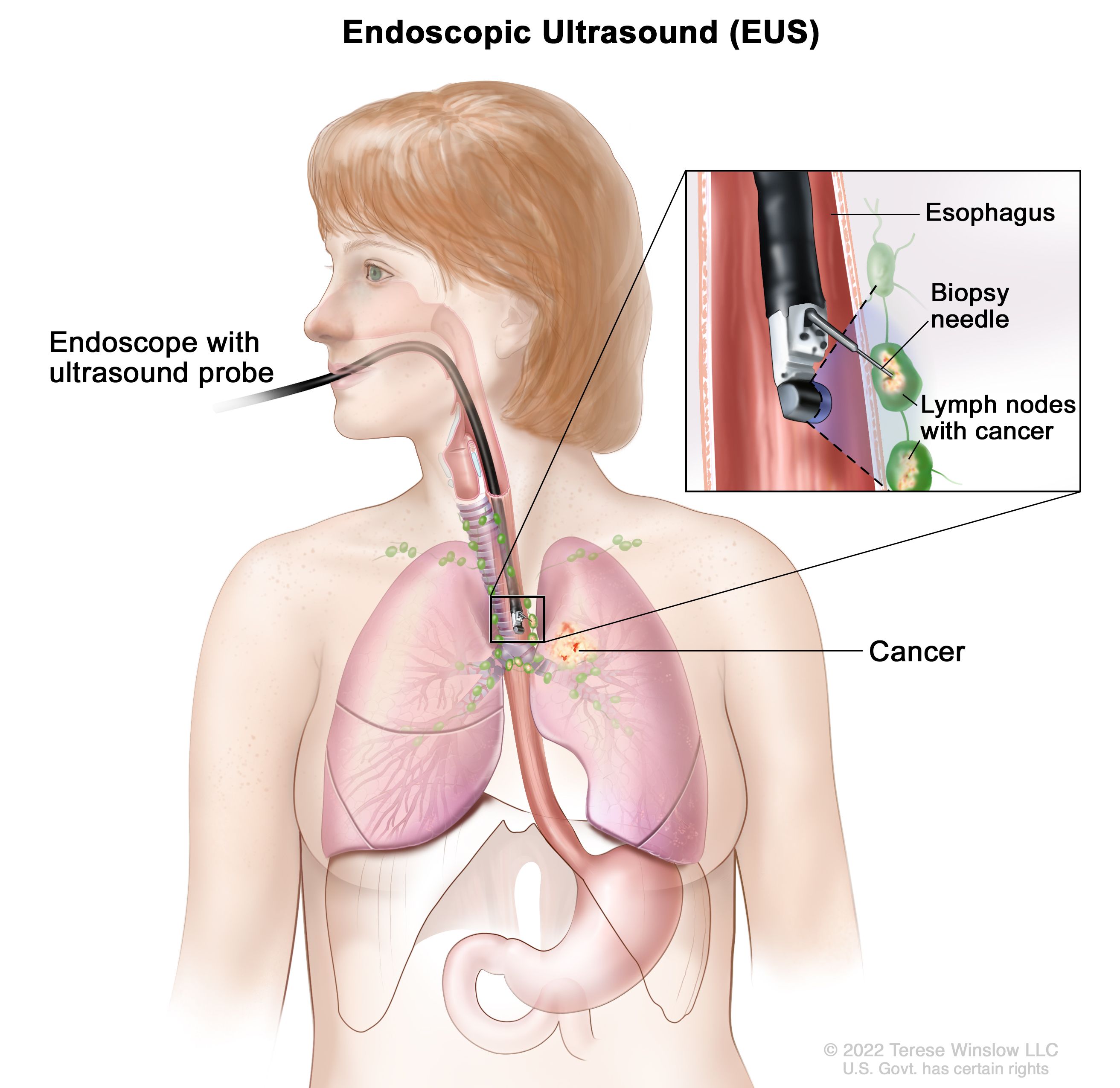

For tumors suspected in the stomach or proximal GI tract, upper endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy) is commonly employed. Gastric GIST typically appear as submucosal masses and may demonstrate overlying ulceration. However, due to their subepithelial location, standard mucosal biopsies often fail to yield diagnostic material. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), combined with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) or core biopsy, significantly improves diagnostic yield and is considered a standard tool for evaluating subepithelial GI lesions . Cross-sectional imaging is central to diagnosis and staging. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) is the preferred first-line modality, offering excellent assessment of tumor size, location, enhancement pattern, and metastatic spread. GIST commonly present as well-demarcated, enhancing masses with areas of necrosis or hemorrhage. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) serves as an alternative for patients with contraindications to iodinated contrast or when evaluating tumors in anatomically complex areas such as the rectum. In selected cases, especially when evaluating early treatment response or suspected recurrence, positron emission tomography (PET) using fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET) can be helpful due to its sensitivity to metabolic changes.

Histological confirmation remains essential. For lesions not amenable to EUS-FNA, image-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy may be performed, though caution is required to avoid tumor rupture or seeding. Microscopically, GIST exhibit spindle cell, epithelioid, or mixed morphology. Mitotic count is a critical feature for risk stratification. Immunohistochemistry is pivotal for confirming the diagnosis. Most GIST are strongly positive for CD117 (c-KIT), which is a defining diagnostic marker. DOG1 (Discovered on GIST-1) is another highly sensitive and specific marker that is particularly useful in KIT-negative cases. CD34 is expressed in the majority of GIST but lacks specificity. These markers distinguish GIST from other mesenchymal tumors such as leiomyomas, schwannomas, or desmoids (American Cancer Society).

Treatment Options

The treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) involves a range of modalities tailored to tumor characteristics such as size, location, mutational profile, and stage of disease. The cornerstone of therapy for localized, resectable tumors is surgical resection with negative margins. In cases where tumors are borderline resectable or located in anatomically challenging areas, neoadjuvant therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) may be used to downstage the disease prior to surgery. For patients at high risk of recurrence, adjuvant therapy—typically with imatinib—is employed following resection. In advanced, unresectable, or metastatic disease, systemic therapy with TKIs remains the standard of care, with several lines of treatment available depending on mutational status and prior response. Additional therapeutic options include local liver-directed interventions for isolated metastases, palliative radiotherapy for symptomatic lesions, and emerging investigational strategies such as immunotherapy and novel targeted agents currently being explored in clinical trials.

Treatment

The treatment strategy for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) is determined by multiple factors, including tumor size, location, resectability, mutational status, metastatic spread, and patient fitness. According to the 2024 NCCN Guidelines, the current management of GIST is centered around a combination of surgery, targeted systemic therapy, and in selected cases, interventional radiology or radiotherapy, while conventional chemotherapy is generally ineffective and not recommended.

For patients with localized and resectable GIST, surgical resection is the primary and potentially curative modality. The goal of surgery is complete excision with negative margins, preserving the pseudocapsule and avoiding rupture. Extended or multivisceral resections are discouraged unless necessary, and lymphadenectomy is not routinely indicated, except in specific subtypes such as SDH-deficient or pediatric GIST. A minimally invasive approach may be considered for favorable anatomic locations. For resectable tumors associated with significant surgical morbidity—such as those located in the rectum, esophagus, or duodenum—or when tumor downsizing could facilitate organ preservation, neoadjuvant therapy is indicated. Imatinib is the first-line agent for tumors with KIT or PDGFRA mutations (excluding PDGFRA D842V), while avapritinib is recommended for PDGFRA D842V-mutant GIST. Treatment duration may extend up to 6 months or more to achieve maximal response before surgery.

Adjuvant therapy with imatinib is recommended for patients at intermediate or high risk of recurrence, particularly those with KIT- or PDGFRA-sensitive mutations. A 3-year duration is standard, although emerging data support consideration of longer treatment in selected patients. In cases of unresectable, metastatic, or recurrent GIST, systemic targeted therapy is the cornerstone of treatment. Imatinib remains the first-line agent for most patients. For those with progression or intolerance, second-line treatment includes sunitinib, followed by regorafenib as third-line, and ripretinib as fourth-line therapy. For patients harboring actionable mutations such as NTRK fusions or BRAF V600E, specific inhibitors like larotrectinib, entrectinib, or dabrafenib + trametinib may be considered. SDH-deficient GISTs often require alternate strategies such as sunitinib or enrollment in clinical trials.

Radiotherapy (RT) is not a routine treatment for GIST due to their relative radioresistance. However, palliative RTmay be considered for symptomatic metastatic lesions, such as bone or soft tissue involvement, particularly when other modalities are not feasible. In patients with liver-dominant metastases or limited progression while on TKI therapy, interventional radiologic procedures such as transarterial embolization (TAE), chemoembolization (TACE), radioembolization (TARE), or thermal ablation (RFA, microwave) may offer local disease control. These approaches are reserved for select patients with preserved liver function and limited extrahepatic disease. Finally, chemotherapy has no established role in the management of GIST, as these tumors are inherently resistant to conventional cytotoxic agents. Immunotherapy is also not currently standard but remains under investigation in clinical trials.

This treatment framework emphasizes the necessity of multidisciplinary care, integrating surgical, medical oncology, molecular pathology, and radiology expertise to optimize outcomes. The choice of therapy is mutation-driven, and mutation testing is mandatory before initiating TKI therapy to guide agent selection and predict responsiveness.

Novel Therapies for GIST

In recent years, the treatment landscape of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) has undergone significant expansion, particularly due to the limitations of first-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as imatinib. While imatinib remains the cornerstone for most KIT- or PDGFRA-mutant GIST, primary or acquired resistance inevitably develops in a substantial proportion of patients, necessitating alternative therapeutic strategies. Advances in molecular profiling and precision oncology have catalyzed the development of novel therapies aimed at overcoming resistance and targeting previously untreatable subtypes.

Among the most notable advancements is the development of next-generation TKIs. Avapritinib, a selective inhibitor of PDGFRA, has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in tumors harboring the PDGFRA D842V mutation, a genotype historically resistant to imatinib. Its approval for this indication represents a major milestone in genotype-directed therapy. Ripretinib, another innovative agent, is a switch-control TKI that inhibits a broad spectrum of KIT and PDGFRA mutants, including activation loop mutations associated with resistance to earlier lines of therapy. Approved for use in the fourth-line setting, ripretinib offers a new option for patients with multi-drug refractory GIST. Emerging compounds such as bezuclastinib (CGT9486) are under investigation, particularly for their activity against exon 17 KIT mutations, and may expand future options when used alone or in combination.

Beyond classical KIT and PDGFRA targets, newer agents have been introduced to address non-canonical driver mutations. In the rare subset of GIST with NTRK gene fusions, targeted agents such as larotrectinib and entrectinibhave shown robust responses, highlighting the importance of comprehensive molecular testing. Likewise, BRAF V600E mutations, though uncommon, may be actionable with a combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors such as dabrafenib plus trametinib. Additionally, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, often implicated in resistance mechanisms, is under active investigation, with early-phase studies evaluating the efficacy of pathway inhibitors such as everolimus.

SDH-deficient GISTs, which typically lack KIT and PDGFRA mutations, represent a unique subgroup with distinct epigenetic and metabolic profiles. These tumors frequently affect younger patients and are often resistant to standard TKI therapy. Research is currently exploring the therapeutic potential of epigenetic modulators, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) inhibitors, and metabolic interventions aimed at exploiting the tumor’s altered oxidative and methylation pathways. Importantly, these tumors exhibit immune-infiltrated microenvironments, prompting interest in immunotherapy, including immune checkpoint inhibitors and immune-modulating combinations. Although single-agent checkpoint blockade has shown limited efficacy in unselected GIST populations, specific immunogenic subtypes like SDH-deficient GIST may respond differently, a hypothesis currently being tested in ongoing clinical trials.

Combination strategies are also being explored to overcome clonal heterogeneity and adaptive resistance. These include dual TKI regimens, such as combining imatinib with mTOR inhibitors, as well as adaptive treatment approaches that tailor therapy based on evolving tumor response patterns. Furthermore, novel therapeutic platforms such as antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) targeting overexpressed antigens like KIT or DOG1, and cell-based therapies including CAR-T cells, are in early stages of development and may offer future treatment possibilities.

You Can Watch More on OncoDaily Youtube TV

Written by Toma Oganezova, MD

FAQ

What are gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST)?

GISTs are rare tumors that develop from interstitial cells of Cajal in the digestive tract, most commonly in the stomach or small intestine.

What causes GIST?

Most GISTs are caused by mutations in the KIT or PDGFRA genes, which lead to uncontrolled cell growth. Some cases are linked to inherited syndromes or are wild-type (no known mutations).

What are common symptoms of GIST?

Symptoms may include abdominal pain, bloating, gastrointestinal bleeding, fatigue, nausea, early satiety, or a palpable mass. Some tumors are asymptomatic.

How are GIST diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves imaging (CT/MRI), endoscopy with biopsy, and immunohistochemistry testing for markers like CD117 (KIT) and DOG1. Genetic testing helps guide treatment.

Are GIST cancerous?

Yes, GIST are considered malignant, though their behavior can range from indolent to aggressive. Risk depends on size, location, and mitotic activity.

What is the main treatment for localized GIST?

Surgery is the first-line treatment for resectable GIST. The goal is complete removal with negative margins without rupturing the tumor.

What is the role of imatinib in GIST treatment?

Imatinib (Gleevec) is a targeted therapy used as neoadjuvant (before surgery), adjuvant (after surgery), or primary treatment in metastatic/unresectable cases with sensitive mutations.

What happens if GIST becomes resistant to imatinib?

Second- and third-line TKIs like sunitinib, regorafenib, and ripretinib are used. Novel agents and clinical trials may also be options, especially for rare mutations.

Can GIST be cured?

Localized GIST can often be cured with surgery and/or adjuvant therapy. Metastatic cases can be controlled long-term with TKIs, though a cure is rare.

Why is genetic testing important in GIST?

Mutation testing for KIT, PDGFRA, and others determines the best treatment approach, as some mutations (e.g., PDGFRA D842V) are resistant to certain therapies like imatinib.

-

Challenging the Status Quo in Colorectal Cancer 2024

December 6-8, 2024

-

ESMO 2024 Congress

September 13-17, 2024

-

ASCO Annual Meeting

May 30 - June 4, 2024

-

Yvonne Award 2024

May 31, 2024

-

OncoThon 2024, Online

Feb. 15, 2024

-

Global Summit on War & Cancer 2023, Online

Dec. 14-16, 2023