When new cancer treatments are discussed, whether in clinical trials, regulatory approvals, or patient consultations, two outcome measures appear repeatedly: progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). These endpoints are central to how therapies are evaluated, approved, and ultimately used in clinical practice. Yet they are often misunderstood, conflated, or debated, even among experienced clinicians.

The question “Progression-Free Survival vs Overall Survival: which matters more?” has no universal answer. Instead, it reflects a deeper discussion about what constitutes meaningful benefit in cancer care, how trials are designed, and how patients experience treatment. Understanding the differences between PFS and OS and the contexts in which each is most informative, is essential for interpreting oncology data responsibly.

What Is Progression-Free Survival?

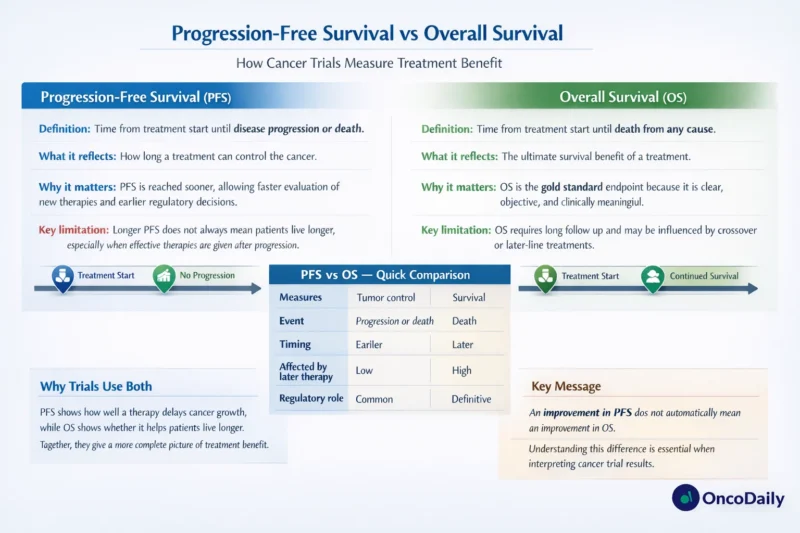

Progression-free survival refers to the length of time from the start of treatment until disease progression or death from any cause, whichever occurs first. Progression is typically defined using standardized criteria such as RECIST, based on imaging, clinical findings, or biomarker changes.

PFS does not require a patient to live longer; it measures how long the cancer remains under control. In practice, PFS captures whether a treatment delays tumor growth, spread, or recurrence.

Because progression events often occur earlier than death, PFS can be assessed sooner and with fewer patients than OS. This makes it an attractive endpoint for clinical trials, especially in advanced or heavily pretreated populations.

What Is Overall Survival?

Overall survival is defined as the time from treatment initiation (or randomization in a trial) until death from any cause. It is the most definitive and objective endpoint in oncology. Unlike PFS, OS is not dependent on imaging schedules, assessment criteria, or investigator interpretation.

OS directly answers the question most patients ask: Does this treatment help me live longer?

However, OS requires longer follow-up, larger patient populations, and can be influenced by many factors beyond the study treatment, including subsequent therapies received after progression.

Why Overall Survival Has Traditionally Been Considered the “Gold Standard”

Historically, OS has been regarded as the most meaningful and patient-centered endpoint. It is unambiguous, clinically intuitive, and free from assessment bias. From a regulatory and ethical perspective, demonstrating an improvement in OS provides clear evidence that a therapy changes the natural history of a disease.

For decades, many landmark cancer treatments, such as curative chemotherapies and early targeted agents were approved based on unequivocal OS benefits. This established a strong cultural expectation within oncology that OS should be the primary benchmark of success.

Why Progression-Free Survival Became So Prominent

As cancer treatment evolved, particularly with the advent of targeted therapies and immunotherapies, relying solely on OS became increasingly challenging.

Several factors contributed to the rise of PFS as a key endpoint:

- First, subsequent lines of therapy can dilute OS differences. In modern oncology, patients often receive multiple effective treatments after progression. Even if a first-line therapy substantially delays progression, OS may appear similar between trial arms because patients cross over or receive active salvage treatments.

- Second, ethical trial designs frequently allow crossover. When patients in the control arm are permitted to receive the experimental therapy after progression, detecting an OS difference becomes difficult, even if the drug is clearly active.

- Third, earlier readouts are critical for rapidly advancing therapies in aggressive diseases. PFS allows investigators and regulators to identify benefit sooner, which can be particularly important in settings with high unmet need.

Clinical Meaningfulness: Does PFS Reflect Real Benefit?

The central controversy in the Progression-Free Survival vs Overall Survival debate is whether delaying progression meaningfully improves patient outcomes.

In some cases, longer PFS clearly matters. Delaying progression can reduce symptoms, prevent complications, and maintain organ function. For example, preventing brain metastases, spinal cord compression, or visceral crisis has obvious clinical value even if OS is unchanged.

In other scenarios, PFS improvements may not translate into better quality of life. A modest delay in radiographic progression that comes with significant toxicity may offer limited real-world benefit from a patient perspective.

Therefore, PFS must be interpreted in context, ideally alongside patient-reported outcomes, symptom control, and toxicity data.

Disease Context Strongly Influences Which Endpoint Matters More

The relative importance of Progression-Free Survival vs Overall Survival depends heavily on disease type and setting.

In curative or early-stage cancers, OS (or disease-free survival as a surrogate) is generally more meaningful. Patients and clinicians expect treatments to improve long-term survival or cure rates, not merely delay recurrence.

In advanced, incurable cancers, especially those with multiple effective treatment options, PFS often becomes a practical and informative endpoint. Here, maintaining disease control, preserving quality of life, and delaying the need for more toxic therapies can be highly valuable goals.

In rare cancers or biomarker-defined subgroups, achieving statistically powered OS analyses may be unrealistic. In such cases, robust and durable PFS improvements can reasonably support clinical benefit.

Regulatory Perspectives on PFS and OS

Regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency accept both PFS and OS as valid endpoints, depending on context.

OS remains the preferred endpoint when feasible. However, PFS is commonly used to support approvals, particularly accelerated approvals, when it reflects a clear and meaningful effect on tumor biology.

Importantly, regulators increasingly emphasize the totality of evidence, including PFS magnitude, durability of response, safety profile, and patient-reported outcomes. A statistically significant PFS benefit alone is rarely sufficient unless it is clinically substantial and supported by additional data.

Statistical and Methodological Considerations

From a methodological standpoint, PFS is more susceptible to bias than OS. Differences in imaging frequency, assessment timing, and investigator interpretation can influence PFS results. Independent central review is often used to mitigate this risk.

OS, while more robust, is not immune to confounding. Post-progression therapies, crossover, and evolving standards of care can obscure true treatment effects.

Neither endpoint is perfect. Understanding their limitations is critical when interpreting trial results and translating them into practice.

What Patients Often Value Most

When discussing Progression-Free Survival vs Overall Survival with patients, clinicians often find that priorities vary.

Some patients prioritize living as long as possible, even if it involves aggressive treatment. Others place greater value on symptom control, treatment-free intervals, and maintaining daily function.

For many, delaying progression is meaningful if it allows them to feel well, avoid hospitalization, or postpone more toxic therapies. For others, PFS gains without OS benefit may feel abstract or insufficient.

Clear communication about what PFS and OS represent and what a given trial result actually means for an individual patient is essential.

Read About Remission vs Cure on OncoDaily

Integrating PFS and OS in Clinical Decision-Making

Rather than asking which endpoint matters more in absolute terms, a more useful approach is to ask how PFS and OS together inform value.

A therapy that improves PFS substantially, has manageable toxicity, and preserves quality of life may be highly valuable even without a proven OS benefit. Conversely, a marginal PFS gain with significant toxicity and no OS signal warrants caution.

The most informative trials increasingly integrate multiple endpoints, allowing clinicians to assess not just whether patients live longer, but how they live during that time.

Conclusion: It Is Not Either Or

The debate over Progression-Free Survival vs Overall Survival often oversimplifies a complex issue. OS remains the most definitive endpoint, but PFS plays a crucial role in modern oncology, particularly in advanced disease and rapidly evolving therapeutic landscapes.

Rather than viewing PFS and OS as competing measures, they should be understood as complementary. Each provides different insights into treatment benefit, and neither should be interpreted in isolation.

Ultimately, the endpoint that “matters more” depends on disease context, available therapies, patient priorities, and the balance between efficacy and quality of life. Thoughtful interpretation, rather than rigid hierarchy, is what truly advances patient-centered cancer care.

Written by Armen Gevorgyan, MD