Henrietta Lacks, born Loretta Pleasant on August 1, 1920, in Roanoke, Virginia, grew up in rural poverty on her family’s tobacco farm in Clover, Virginia, after her mother’s death. Married to steelworker David “Day” Lacks at age 14, she bore five children amid challenging living conditions; by 1951, the family had relocated to Baltimore for wartime factory work. On January 29, 1951, persistent vaginal spotting prompted her visit to Johns Hopkins Hospital—the sole major hospital then treating Black patients in segregated Baltimore where gynecologist Howard Jones diagnosed a malignant cervical tumor, later confirmed as epidermoid carcinoma with adenocarcinoma features, likely HPV-related.

Photo: Depositphotos

During radium tube insertion for brachytherapy on February 5 by resident surgeon Lawrence Wharton Jr., a small biopsy (about 1 cm²) was excised from the tumor’s edge without Lacks’ knowledge or consent a standard but ethically fraught practice in the Jim Crow era when tissue from poor Black patients was routinely harvested for research without disclosure.

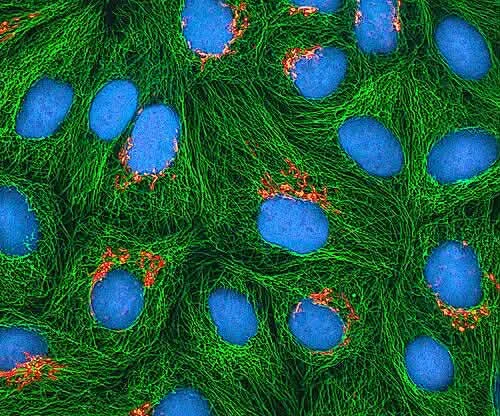

The sample reached George Otto Gey, Johns Hopkins’ pioneering tissue culturist, via his assistant Mary Kubicek, who processed it in a sterile roller-drum apparatus using a nutrient medium of chicken plasma, calf serum, and human umbilical cord blood. Gey’s prior attempts with cells from breast cancer, kidney, and other sources had failed after 2-3 divisions due to senescence governed by the Hayflick limit (typically 50-70 doublings before telomere shortening halts replication).

Remarkably, Lacks’ cells dubbed “HeLa” from her first and last initials for anonymity exhibited exponential growth, dividing every 20-24 hours indefinitely. This immortality stemmed from upregulated human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT), which adds TTAGGG repeats to chromosome ends, countering erosion; HeLa’s karyotype showed chromosomal instability (aneuploidy, modal 76 chromosomes) yet robust proliferation. Gey confirmed viability by May 1951, sharing cultures with colleagues like William Scherer and Jerome Vineland; a June press conference announced the breakthrough just before Lacks’ death from uremia on October 4, 1951, at age 31. Posthumously, her cells contaminated and supplanted other lines globally, becoming the workhorse of biology.

Research Dissemination

HeLa proliferated via free exchange: by 1953, the lab produced tons annually; today, >100,000 trillion cells support 110,000+ papers (e.g., 25% of PubMed cell biology abstracts) and 11,000 patents, from Salk’s 1954 polio vaccine (tested in HeLa) to CRISPR editing. No “50,000 metric tons” figure holds in sources; instead, cumulative output equates to billions of vials from ATCC and collaborators.

Historical Context of Consent Issues

In 1951, Henrietta Lacks’ tumor biopsy was taken without explicit informed consent, reflecting standard practices at Johns Hopkins where tissue from indigent, often Black patients was routinely used for research amid Jim Crow-era segregation. Dr. George Gey and surgeon Lawrence Wharton operated under the era’s “physician knows best” paradigm no federal regulations like the 1974 National Research Act existed, and consent forms were rare before the 1960s Nuremberg Code influences.

Statue of Henrietta Lacks by sculptor Helen Wilson-Roe at Royal Fort House, Bristol, Phoro: Wikimedia Commons

Lacks’ family remained unaware for over 20 years; cells were commercialized (e.g., via ATCC by 1955) generating millions, yet they received no benefits or recognition until journalist Rebecca Skloot’s 2010 book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks spotlighted the injustice. This non-consensual harvesting exemplifies “hela-pization” of research ethics, prompting modern IRB mandates under 45 CFR 46.

Racial Disparities in Cervical Cancer

Black women face 63% higher cervical cancer incidence and 64% higher mortality than white women in the U.S., per CDC data, mirroring Lacks’ untreated adenocarcinoma in underserved communities. HeLa’s HPV18-linked oncogenesis (E6/E7 inactivation of p53/Rb) underscores disparities: lower screening access delays diagnosis, yet HeLa-derived vaccines (Gardasil, Cervarix) prevent 90% of HPV-attributable cases when equitably deployed. Critiques highlight irony Lacks’ cells advanced global oncology while her community grapples with barriers like poverty and mistrust from Tuskegee-like abuses.

Family Recognition and Advocacy Efforts

The Lacks family gained visibility post-1973 when researchers contacted Deborah Lacks for blood samples, revealing HeLa’s identity via contaminated cultures. Milestones include:

- 2013: NIH agreement for controlled HeLa genomic data access after family advocacy.

- 2021: WHO Director-General Tedros Ghebreyesus honored Henrietta in the gallery of “unsung heroes,” acknowledging her contributions sans consent.

- Ongoing: Lacks v. Purdue U (2023) lawsuit seeks profit-sharing; family partners with JAMA Oncology for awareness.

Current Scientific Vitality and Debates: The Role and Ethics of HeLa Cells

HeLa cells’ tractability continues to shine in modern oncology applications, particularly in immunotherapy, checkpoint inhibitors, and gene editing, directly advancing NCCN and ASCO guidelines. For CAR-T validation, HeLa cells express CD19 and CD20 via lentiviral transduction with over 90% efficiency, allowing researchers to test chimeric antigen receptor killing kinetics, such as those involving CD3ζ-41BB CARs, as detailed in 2022 studies that optimized IL-2 independence in HeLa co-cultures. This bridges preclinical work to solid tumor CAR-T therapies, including clinical trials like NCT04557436, while modeling cervical and HPV-positive CAR targets such as MUC16.

In PD-L1 assays, HeLa cells endogenously express PD-L1, which is upregulated by IFNγ, enabling flow cytometry and EC50 measurements for drugs like atezolizumab and pembrolizumab binding. CRISPR-mediated PD-L1 knockouts in these cells quantify resistance mechanisms, with 2023 publications linking findings to HPV E6/E7 pathways. These assays guide combination therapies, such as PD-1 inhibitors paired with bevacizumab, and predict responses in approximately 40% of HPV-positive head and neck cancers.

For CRISPR screens targeting oncogenes, genome-wide Cas9 libraries like GeCKO v2, containing 120k sgRNAs, identify synthetic lethals in HeLa cells, with 2020s hits including telomerase regulators and PI3K/AKT inhibitors. Their high post-editing viability, exceeding 70% and outperforming HEK293 cells, has fueled over 500 such screens in 2023 alone. This uncovers druggable vulnerabilities, for example, WEE1 inhibitors effective against p53-null tumors akin to HeLa’s profile.

Beyond these core uses, HeLa supports HPV vaccine R&D by assessing Gardasil9 efficacy through E6/E7 neutralization assays. It also facilitates radiation sensitization studies with IR-808 dyes for photodynamic therapy and xenografts in nude mice to evaluate cisplatin/fluoxetine synergy from 2014 through 2024 extensions. During the COVID era, HeLa modeled SARS-CoV-2 entry via ACE2 transfection, informing oncolytic virotherapy strategies relevant to cancer treatment.

Turning to genetic rights debates and 2023 ELSI guidelines, the post-2013 NIH genomic data embargo—established after Lacks family advocacy—intensified discussions over “genetic colonialism.” Core issues include HeLa’s 2022 full genome sequence, revealing 60,000 mutations and HPV18 integration, which poses risks to family identifiability alongside commercial profits from sales by companies like Thermo Fisher without royalties, underscoring exploitation.

The 2023 ELSI guidelines, or Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications framework from NHGRI/NIH, urge tiered data access with public aggregates and controlled individual-level information. They recommend benefit-sharing models, such as allocating 1-5% of profits to donor communities through initiatives like Henrietta Lacks Foundation grants for Black-led cancer research, along with community veto rights on sensitive applications like germline edits. This approach balances open science under FAIR principles with equity, influencing programs like H3ABioNet in Africa.

Outcomes include a 2023 settlement in Lacks v. biotech firms that mandated acknowledgments in publications and products. The WHO’s 2021 honor for Henrietta Lacks extended to data governance training efforts. Ongoing ASCO equity taskforces now cite the HeLa case to promote diverse biobanking practices in oncology research.

You Can Also Read Epigenetic Modifiers in Cancer Therapy: Unlocking New Treatment Pathways by OncoDaily

Written by Aharon Tsaturyan, MD, Editor at OncoDaily Intelligence Unit

FAQ

What are HeLa cells?

HeLa cells are the first immortalized human cell line, derived from Henrietta Lacks' cervical adenocarcinoma in 1951; they divide indefinitely every 20-24 hours due to upregulated telomerase (hTERT), modeling tumor aneuploidy with a modal 76 chromosomes.

How were HeLa cells discovered?

On February 5, 1951, during radium brachytherapy at segregated Johns Hopkins Hospital, surgeon Lawrence Wharton Jr. biopsied Lacks' tumor (1 cm² sample) without consent; George Gey's assistant Mary Kubicek cultured them in roller-drums using chicken plasma and serum, succeeding where prior cells senesced.

Why are HeLa cells called 'HeLa'?

Named from the first two letters of Henrietta Lacks' first and last names (He from Henrietta, La from Lacks) to preserve anonymity, as confirmed by Gey in his May 1951 viability tests and June press conference.

What is the ethical controversy with HeLa cells?

Cells were harvested without informed consent—a 1950s norm amid Jim Crow segregation—leading to commercialization (e.g., ATCC by 1955) and profits without family benefits; this spurred modern IRBs (45 CFR 46) and debates on "hela-pization" of ethics.

What medical breakthroughs came from HeLa cells?

Beyond oncology, HeLa supported Salk's 1954 polio vaccine, HIV drug testing, human genome mapping, and COVID-19 entry modeling; it underpins 110,000+ papers (25% of cell biology PubMed abstracts) and 11,000 patents.

Are HeLa cells still used in research today?

Yes, vital for 2020s oncology: >80% transfection efficiency beats HEK293, models p53-null tumors for WEE1 inhibitors, and drives NCCN/ASCO advances amid 2023 ELSI guidelines for benefit-sharing and tiered genomic access.

Who was Henrietta Lacks?

Henrietta Lacks (born Loretta Pleasant on August 1, 1920, in Roanoke, Virginia) was a Black American tobacco farmer and mother of five who died of cervical cancer at age 31; her tumor cells became the HeLa cell line without her consent.

How have HeLa cells impacted cancer research?

HeLa enabled HPV18 discovery (E6/E7 oncogenes), Gardasil vaccines preventing 90% of cases, CAR-T validation (CD19/CD20 transduction), PD-L1 assays for pembrolizumab, CRISPR oncogene screens (500+ in 2023), and xenografts for cisplatin synergy.

Did Henrietta Lacks' family get recognition or compensation?

Family learned in 1973 via blood draws revealing HeLa contamination; milestones include 2013 NIH data access deal, WHO's 2021 "unsung hero" honor by Tedros Ghebreyesus, and 2023 Lacks v. biotech settlements mandating acknowledgments.

Why do Black women still face higher cervical cancer rates?

U.S. Black women have 63-64% higher incidence/mortality (CDC data) due to screening barriers, poverty, and Tuskegee-era mistrust—ironic given HeLa's HPV vaccine role, yet underscoring equity gaps Lacks' story highlights.