Patients diagnosed with metastatic cancer often search for clear answers about prognosis. One of the most common questions is simple and deeply human: What is the cure rate? Yet clinicians and researchers rarely use this term when discussing metastatic disease. Understanding why cure rates are rarely used in metastatic cancer is essential for interpreting clinical data, managing expectations, and appreciating how progress in oncology is truly measured.

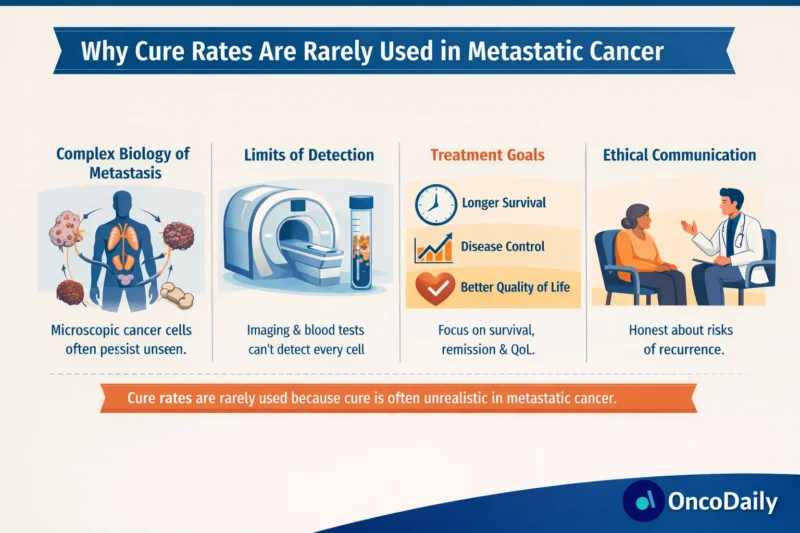

The avoidance of “cure rate” is not about pessimism or lack of progress. Rather, it reflects the biological nature of metastatic disease, the limitations of current diagnostic tools, and the way cancer outcomes are responsibly measured in modern oncology.

What Does “Cure” Mean in Oncology?

In everyday language, cure implies permanent eradication of disease, with no chance of return. In oncology, however, cure has a stricter and more cautious meaning. A cancer is considered cured only when the likelihood of recurrence becomes negligible over a long period of follow-up, often measured in decades rather than years.

This definition works reasonably well for some early-stage cancers treated definitively with surgery or radiotherapy. In metastatic cancer, however, the situation is fundamentally different, which is central to understanding why cure rates are rarely used in metastatic cancer.

The Biology of Metastatic Cancer

Metastatic cancer is defined by the spread of malignant cells from the primary tumor to distant organs. This process is not simply a matter of tumor size or location but reflects complex biological behavior. Metastatic cancer cells often possess genetic diversity, treatment resistance, and the ability to survive in multiple tissue environments.

Even when imaging shows dramatic tumor regression or complete disappearance, microscopic disease may persist. These residual cells can remain dormant for long periods before reactivating. Because current imaging and molecular tests cannot reliably confirm total eradication of all cancer cells, declaring cure becomes scientifically unsound (Chaffer & Weinberg, 2011). This biological uncertainty is one of the core reasons why cure rates are rarely used in metastatic cancer.

Limitations of Detection and Measurement

Modern imaging techniques such as CT, MRI, and PET scans have improved dramatically, yet they still detect disease only above certain thresholds. Small clusters of cancer cells can escape detection and later seed recurrence.

Liquid biopsy and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) testing have expanded sensitivity, but these technologies are still evolving and cannot guarantee complete absence of disease (Pantel & Alix-Panabières, 2019). As long as detection has limits, cure cannot be stated with confidence in metastatic disease.

Historical Outcomes in Metastatic Cancer

Historically, metastatic cancer was almost universally fatal within a short timeframe. While this is no longer always the case, especially with targeted therapies and immunotherapy, long-term survival without recurrence remains uncommon for most metastatic solid tumors.

Large population-based analyses consistently show that metastatic disease is associated with high recurrence rates, even after strong initial responses to treatment (Siegel et al., 2024). These patterns reinforce why cure rates are rarely used in metastatic cancer, even as survival improves.

How Oncology Measures Success Instead of Cure

Because cure is rarely achievable or measurable in metastatic disease, oncology relies on alternative endpoints that better reflect meaningful benefit.

Overall survival measures how long patients live after diagnosis or treatment initiation. Progression-free survival evaluates how long disease remains controlled before growing again. Objective response rate assesses tumor shrinkage. Quality-of-life metrics capture symptom burden and functional status.

These endpoints allow clinicians to quantify benefit without implying permanent eradication. They are more honest, reproducible, and clinically useful than cure rates in metastatic settings (FDA Oncology Center of Excellence, 2023).

Read About Chemotherapy Success Rate on OncoDaily

Exceptional Responders and the “Functional Cure” Concept

Occasionally, patients with metastatic cancer experience extraordinary long-term disease control, sometimes lasting many years. These cases are often referred to as exceptional responders.

Even in these situations, oncologists are careful. Rather than using cure, terms such as durable remission or functional cure may be applied. Functional cure implies that cancer behaves like a chronic condition that no longer impacts lifespan or quality of life, even if microscopic disease may persist (Topalian et al., 2019).

The rarity of such outcomes further explains why cure rates are rarely used in metastatic cancer as a population-level metric.

Immunotherapy and Changing Expectations

The rise of immune checkpoint inhibitors has challenged traditional thinking in oncology. In diseases such as metastatic melanoma and certain lung cancers, a subset of patients now experience long-term survival that was previously unimaginable.

However, even in these settings, cure rates are still not routinely reported. Long-term follow-up reveals that late relapses can occur, and predictive biomarkers for permanent eradication remain imperfect (Robert et al., 2020). As a result, the field continues to favor survival-based endpoints over cure statistics.

Ethical Communication and Patient Trust

Another key reason why cure rates are rarely used in metastatic cancer lies in ethical communication. Overstating certainty can harm patients psychologically and undermine trust if recurrence occurs after a “cure” has been implied.

Clear, honest language helps patients make informed decisions, plan their lives, and engage in realistic hope. Hope in metastatic cancer is increasingly centered on living longer and better, not on promises that cannot be scientifically guaranteed.

Statistical Challenges of Cure Rates

From a methodological perspective, cure rates require very long follow-up and clear separation between cured and non-cured populations. In metastatic cancer, survival curves often do not plateau in a way that allows reliable estimation of cure fractions.

Advanced statistical models exist to estimate cure proportions, but they are rarely robust enough for routine clinical use in metastatic disease (Othus et al., 2012). This statistical uncertainty further contributes to why cure rates are rarely used in metastatic cancer research and reporting.

The Shift Toward Chronic Disease Management

Modern oncology increasingly views metastatic cancer as a chronic condition for many patients. Continuous treatment, treatment sequencing, and adaptive strategies allow patients to live for years with controlled disease.

In this framework, cure becomes less relevant than durability, tolerability, and quality of life. Reporting cure rates would fail to capture the lived reality of patients whose disease is managed over time rather than eradicated.

Why This Matters for Patients and Caregivers

Understanding why cure rates are rarely used in metastatic cancer helps patients interpret clinical news, trial results, and media headlines more accurately. A treatment that does not “cure” cancer can still add meaningful years of life, relieve symptoms, and allow patients to reach personal milestones.

This perspective also empowers patients to ask better questions, focusing on expected disease control, side effects, and quality of life rather than an elusive cure statistic.

Looking Ahead

Research continues to push boundaries. Advances in immunotherapy combinations, cellular therapies, precision oncology, and minimal residual disease detection may one day allow more confident use of the word cure in metastatic settings. Until then, restraint in language reflects scientific integrity rather than lack of progress.

For now, why cure rates are rarely used in metastatic cancer comes down to biology, measurement limits, ethical responsibility, and a commitment to accurate communication. Progress in metastatic cancer is real and accelerating, but it is best described through survival, remission, and quality-of-life outcomes rather than cure rates.

You Can Watch More on OncoDaily Youtube TV

Written by Armen Gevorgyan, MD