Over the past decade, immunotherapy has reshaped the treatment landscape for several malignancies, offering durable responses and long-term survival where chemotherapy historically provided only temporary control. Yet colorectal cancer (CRC), one of the most common and deadly cancers worldwide, represents a complex paradox: while a small subgroup responds dramatically to immune checkpoint blockade, the vast majority does not benefit at all.

A new Nature Genetics study (2025) now sheds light on an advanced mechanism of resistance—what researchers describe as a dual immune barriercreated by the tumor through TGF-β signaling.

The following narrative synthesizes foundational concepts, clinical evidence, and the latest mechanistic insights to provide a unified understanding of immunotherapy in CRC.

What Immunotherapy Is and How It Differs From Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy and immunotherapy represent fundamentally different philosophies of cancer treatment. Chemotherapy exerts direct cytotoxicity: it targets rapidly dividing cells by damaging DNA, interfering with mitosis, or disrupting metabolic pathways. It is powerful but non-selective, affecting malignant and healthy cells alike.

Immunotherapy, by contrast, does not target the cancer cell directly. Instead, it activates the patient’s own immune system, particularly T lymphocytes, empowering them to identify and destroy tumor cells. Checkpoint inhibitors lift inhibitory signals such as PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4, restoring antitumor T-cell activity. Cancer vaccines and cellular therapies further enhance immune recognition by introducing tumor-specific antigens or modifying T cells to improve their killing capacity.

This fundamental difference explains the distinct toxicity profiles. Chemotherapy produces predictable, immediate side effects—alopecia, nausea, myelosuppression—because rapidly dividing normal cells are collateral damage. Immunotherapy produces fewer early systemic effects but may cause delayed immune-mediated toxicities affecting the skin, endocrine organs, colon, liver, or lungs.

Understanding these mechanisms helps clinicians predict efficacy across tumor types, and explains why immunotherapy excels in some cancers but has limited benefit in others.

colorectal cancer

You Can Also Read About Immunotherapy vs Chemotherapy: Success Rates, Side Effects, Costs Compared

Success Rates and Clinical Outcomes: Immunotherapy vs Chemotherapy

Across oncology, immunotherapy has dramatically outperformed chemotherapy in cancers with high mutational burden or pre-existing immune activity. Melanoma, NSCLC with high PD-L1 expression, renal cell carcinoma, and Hodgkin lymphoma all demonstrate significantly higher response rates and prolonged survival with checkpoint blockade.

Conversely, chemotherapy remains the backbone for many tumors, such as breast cancer, testicular cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, and early-stage colorectal cancer, where it achieves high cure rates or substantial survival benefits.

The contrasting success of these treatments reflects the biology of each cancer type. Tumors rich in neoantigens or immune infiltration respond better to immunotherapy, whereas those lacking immune visibility remain reliant on cytotoxic chemotherapy.

This principle—immune visibility determines immunotherapy success—is particularly relevant to colorectal cancer.

Immunotherapy in Colorectal Cancer: A Tale of Two Biologies

Colorectal cancer is not immunologically uniform. One subgroup, representing about 5% of metastatic cases, features microsatellite instability (MSI-H) or mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR). These tumors accumulate large numbers of mutations, produce abundant neoantigens, and naturally attract T-cell infiltration.

For these patients, immunotherapy is transformative. Checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab or nivolumab, alone or combined with ipilimumab, yield 40–50% response rates and long-term remissions that were rarely seen previously. In some localized MSI-H/dMMR tumors, neoadjuvant immunotherapy can even produce complete pathological responses.

In striking contrast, the remaining 95% of metastatic CRC cases—microsatellite-stable (MSS) or proficient mismatch repair (pMMR)—do not benefit from immunotherapy. These tumors exhibit low mutational burden, few neoantigens, and minimal immune infiltration. They are considered “cold” tumors and have proven exceptionally resistant to immune-based therapies.

Until now, the reasons behind this profound resistance were only partially understood. A major advance arrived in 2025.

colorectal cancer

Read About Immunotherapy for Colon Cancer: Types, Success Rate, Side Effects & More

New Insights From Nature Genetics (2025): How CRC Builds a Dual Immunologic Barrier

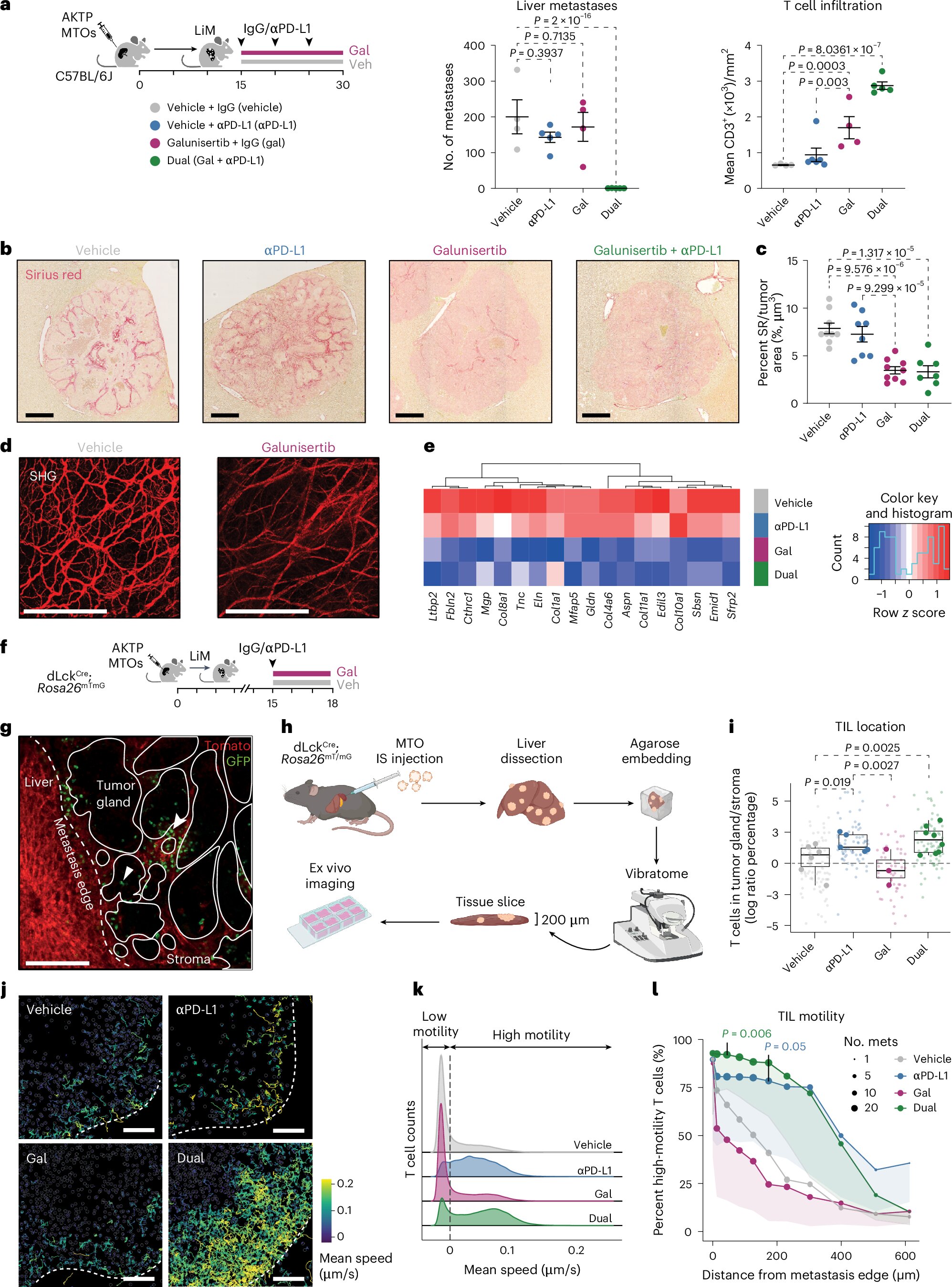

A groundbreaking study from IRB Barcelona and CNAG has revealed why most colorectal tumors evade immunotherapy. Through single-cell RNA sequencing and experimental metastasis models, researchers discovered that CRC uses TGF-β signaling to construct a two-layered defense system that blocks the immune system at multiple levels.

Barrier One: Preventing T-Cell Entry

TGF-β acts as a molecular “no-entry” signal that prevents effector T cells from migrating from the bloodstream into the tumor. Even when circulating tumor-reactive T cells are present, they fail to infiltrate metastatic lesions. This produces an immune desert, where checkpoint inhibitors have no T cells to activate.

Barrier Two: Blocking T-Cell Expansion Inside the Tumor

For the few T cells that successfully infiltrate, the tumor launches a second defensive maneuver. TGF-β reprograms tumor-associated macrophages to produce osteopontin, a protein that suppresses T-cell proliferation and function. Instead of expanding and mounting an immune response, infiltrating T cells become ineffective and rapidly exhausted.

The combination of entry obstruction and intratumoral suppression renders MSS colorectal cancer almost entirely resistant to immunotherapy. The immune system cannot accumulate within the tumor or generate the effector cell population necessary for tumor destruction.

Mechanistic Implications: Why Checkpoint Inhibitors Alone Fail

The study also clarifies why PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors are insufficient in most CRC cases. Releasing the PD-1 brake does not help if:

- T cells never enter the tumor, and

- Those that enter cannot expand or function.

This dual barrier explains decades of clinical trials showing near-universal resistance of MSS CRC to immune checkpoint blockade.

Therapeutic Opportunities: Targeting the “TGF-β Circuit”

Although TGF-β inhibitors have been explored clinically, toxicity limits their widespread use. The new study points toward more precise strategies:

- Blocking downstream mediators such as osteopontin

- Reprogramming macrophages toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype

- Combining TGF-β pathway inhibition with checkpoint blockade

- Using localized or selective TGF-β suppression

- Engineering T cells resistant to TGF-β signaling

In preclinical models, blockade of TGF-β restored T-cell infiltration and enabled formerly resistant tumors to respond robustly to immunotherapy. Combination therapy led to potent antitumor effects, demonstrating that MSS CRC can become immunologically “visible” when the dual barrier is dismantled.