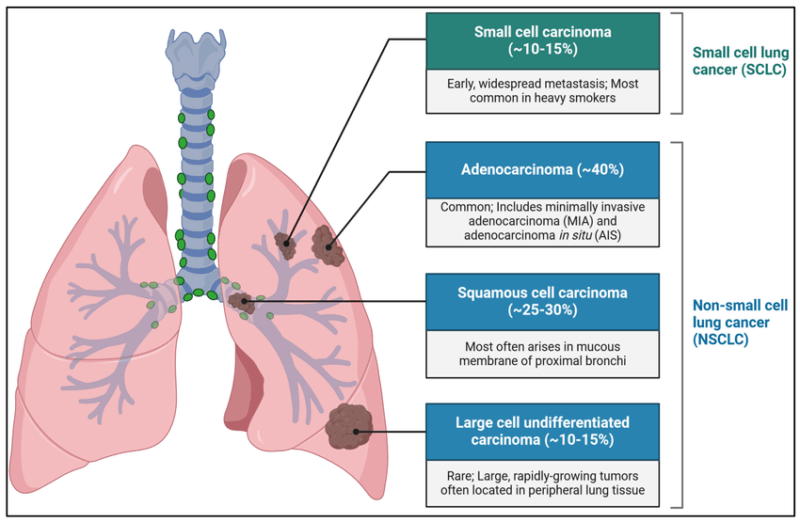

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) represents approximately 85% of all lung cancer diagnoses and is a heterogeneous group of lung malignancies that includes adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma (Travis et al., 2015). Compared to small cell lung cancer (SCLC), NSCLC typically demonstrates slower growth and a lower tendency for early metastasis, offering broader treatment options and a more favorable prognosis when detected early (Herbst et al., 2018).

Types of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) is a broad category that encompasses several histological subtypes. Each type originates from different cell types within the lung and exhibits unique clinical and molecular characteristics. Types of NSCLC are:

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma is the most common type of NSCLC, accounting for approximately 40% of all lung cancers. It typically arises in the peripheral regions of the lung and originates from mucus-secreting glandular cells. This subtype is more common in women and non-smokers and is often detected in the early stages due to its peripheral location. Molecular alterations such as EGFR mutations, ALK rearrangements, and KRAS mutations are frequently seen in adenocarcinomas, making targeted therapy a viable option for many patients (Travis et al., 2015; Sequist & Lynch, 2012).

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for about 25–30% of NSCLC cases and originates from the epithelial cells lining the airways. It is strongly associated with smoking and usually arises in the central part of the lungs, near the main bronchi. Histologically, these tumors show keratinization and intercellular bridges. Unlike adenocarcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas rarely harbor EGFR mutations or ALK translocations but may exhibit FGFR1 amplification or PI3K pathway mutations (Travis et al., 2015; Gazdar et al., 2017).

Large Cell Carcinoma

Large cell carcinoma represents a smaller proportion of NSCLC (approximately 10%) and is considered a diagnosis of exclusion. These tumors lack the glandular differentiation of adenocarcinoma and the squamous features of squamous cell carcinoma. They tend to be poorly differentiated, aggressive, and often diagnosed at an advanced stage. Some large cell carcinomas exhibit neuroendocrine features and are reclassified as large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC), which behaves similarly to small cell lung cancer (Kalemkerian et al., 2013; Travis et al., 2015).

Other Rare Subtypes

These subtypes are identified based on histological examination and immunohistochemistry, which guides treatment planning and prognosis (Travis et al., 2015).

- Adenosquamous carcinoma: Contains both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell components and is more aggressive than either subtype alone.

- Sarcomatoid carcinoma: A rare, poorly differentiated form that shows both epithelial and mesenchymal features. These tumors are highly aggressive and resistant to conventional therapies.

- Pleomorphic carcinoma: Composed of spindle and/or giant cells, this rare form of NSCLC is also associated with a poor prognosis.

These subtypes are identified based on histological examination and immunohistochemistry, which guides treatment planning and prognosis (Travis et al., 2015).

Molecular Subtypes of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

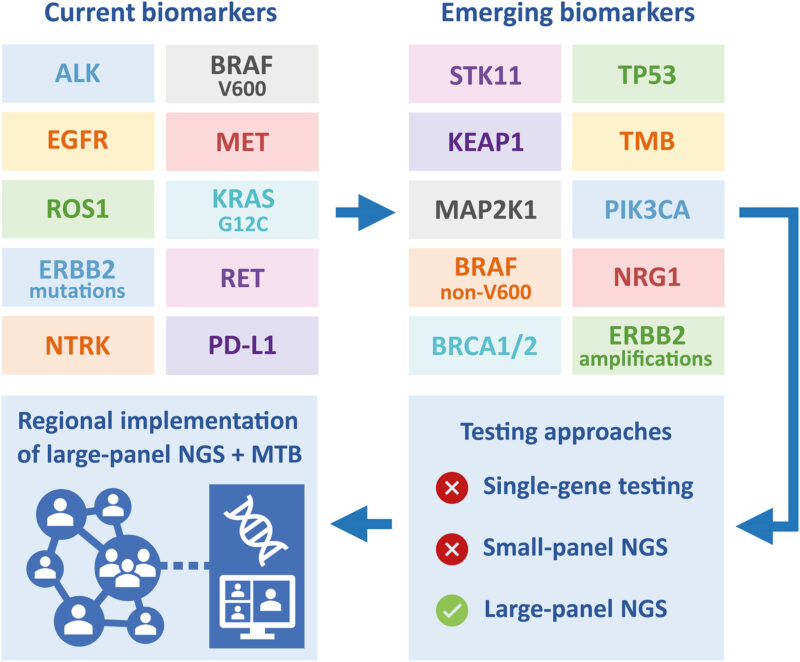

Molecular profiling has transformed the classification and management of NSCLC, especially adenocarcinomas, by identifying driver mutations that guide targeted therapies. The presence of specific genetic alterations allows for a more personalized treatment approach and is critical for improving clinical outcomes. Molecular subtypes of NSCLC are:

EGFR Mutations: Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) mutations are found in approximately 10–15% of NSCLC cases in Western populations and up to 50% in Asian populations. These mutations are most commonly seen in non-smoking females with adenocarcinoma histology. EGFR mutations, particularly exon 19 deletions and exon 21 L858R substitutions, are sensitive to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as osimertinib and erlotinib (Sequist & Lynch, 2012; Travis et al., 2015).

ALK Rearrangements: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene rearrangements occur in 3–5% of NSCLC, often in younger patients with little or no smoking history. These fusions lead to constitutive kinase activity and can be targeted by ALK inhibitors like alectinib, brigatinib, and lorlatinib. Crizotinib was the first approved ALK inhibitor but has largely been replaced by more potent agents with better central nervous system penetration (Rudin et al., 2019).

ROS1 Rearrangements: ROS1 gene fusions are detected in about 1–2% of NSCLC patients and are structurally similar to ALK rearrangements. They are associated with sensitivity to ROS1 inhibitors such as crizotinib and entrectinib. These patients are typically younger and non-smokers with adenocarcinoma histology (Kalemkerian et al., 2013).

BRAF Mutations: BRAF mutations, particularly V600E, occur in approximately 2% of NSCLC cases. These mutations activate the MAPK pathway and are sensitive to targeted therapies like dabrafenib in combination with trametinib, a MEK inhibitor. Non-V600E mutations are less well characterized but may still respond to similar agents (Gazdar et al., 2017).

KRAS Mutations: KRAS mutations are the most common oncogenic drivers in NSCLC, found in about 25–30% of lung adenocarcinomas. They are typically associated with a history of smoking. Until recently, KRAS mutations were considered undruggable, but the development of KRAS G12C inhibitors such as sotorasib and adagrasib has offered promising results in selected patients (George et al., 2015).

MET Exon 14 Skipping Mutations: Alterations in the MET gene, especially exon 14 skipping mutations, lead to oncogenic signaling by impairing degradation of the MET receptor. These mutations occur in about 3% of NSCLC and respond well to MET inhibitors such as capmatinib and tepotinib (Rudin et al., 2019).

RET and NTRK Fusions: RET gene fusions are present in approximately 1% of NSCLC cases, and NTRK gene fusions are even rarer. Both alterations have been effectively targeted by selective inhibitors such as selpercatinib (for RET) and larotrectinib (for NTRK), improving outcomes for patients with these mutations (Gay et al., 2021).

Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) and PD-L1 Expression: Beyond gene mutations, biomarkers like tumor mutational burden and PD-L1 expression are used to predict response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. High PD-L1 expression (≥50%) may indicate benefit from first-line immunotherapy with drugs like pembrolizumab, while high TMB is being evaluated as a potential biomarker for broader immunotherapy use (Horn & Mansfield, 2018).

Molecular subtyping has thus redefined NSCLC as a genetically heterogeneous disease. The identification of actionable mutations has made comprehensive genomic profiling essential in guiding treatment decisions and improving patient survival.

Importance of Molecular Subtyping in NSCLC

The importance of molecular subtyping in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) lies in its ability to guide personalized medicine, which has revolutionized the treatment landscape for lung cancer. By identifying specific genetic alterations such as EGFR mutations, ALK rearrangements, or KRAS variants, clinicians can tailor treatments that directly target the molecular drivers of the tumor. This approach enhances the effectiveness of therapy and minimizes unnecessary toxicity from treatments that may not be beneficial for a patient’s specific cancer profile.

Molecular subtyping also provides valuable prognostic information. Certain mutations are associated with better or worse outcomes, helping physicians predict disease progression and guide clinical decisions. Additionally, understanding the molecular characteristics of a tumor allows for better therapeutic decision-making, such as selecting between targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or traditional chemotherapy.

Furthermore, accurate subtyping is essential for identifying patients who may be eligible for clinical trials investigating novel therapies. This not only broadens treatment options but also contributes to advancing research in lung cancer care. As a result, molecular profiling has become a cornerstone of modern oncology, enabling more precise, effective, and individualized care for patients with NSCLC.

Staging of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Staging is based on the TNM system, which assesses Tumor size (T), lymph Node involvement (N), and Metastasis (M). This helps guide treatment and estimate prognosis.

Stage 0 refers to carcinoma in situ, where abnormal cells are limited to the lung lining without invasion. Stage I involves a tumor confined to the lung without lymph node spread. It is subdivided into IA (tumor ≤3 cm) and IB (tumor >3 cm but ≤4 cm or with certain features). Stage II includes larger tumors or limited lymph node involvement. Stage IIA generally involves tumors 4–5 cm, while Stage IIB includes 5–7 cm tumors or involvement of nearby nodes.

Stage III is locally advanced disease with greater nodal involvement or invasion of nearby structures. Stage IIIA affects lymph nodes on the same side of the chest, while IIIB and IIIC involve more extensive regional spread. Stage IV signifies distant metastases, such as to the opposite lung, liver, brain, or bones. It is divided into IVA (a single distant site) and IVB (multiple sites or organs).NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology.

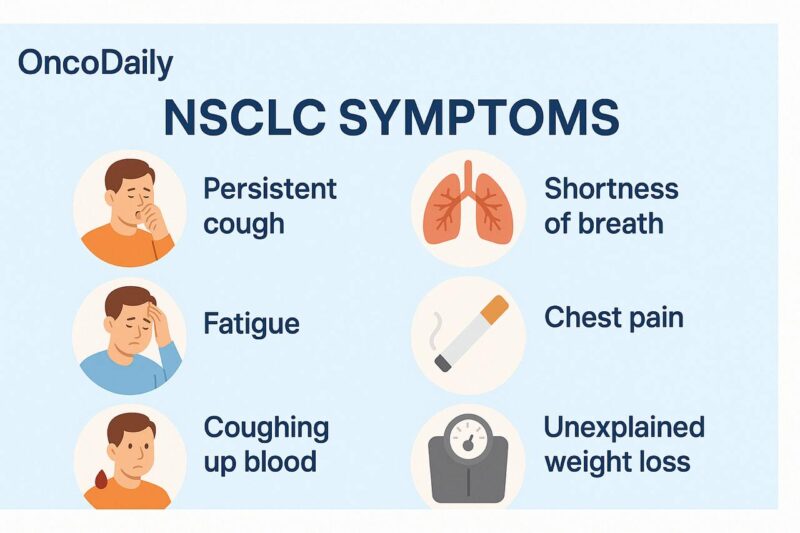

Symptoms of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) symptoms often emerge gradually and can initially mimic those of less serious conditions, making early diagnosis difficult. One of the earliest and most common signs is a persistent cough that does not resolve and may worsen over time. Some individuals may experience chest pain or discomfort, which can intensify with coughing, deep breathing, or laughing.

Shortness of breath (dyspnea) frequently occurs, especially if the tumor obstructs airways or causes fluid buildup around the lungs (pleural effusion). Hoarseness may result from involvement of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, and hemoptysis (coughing up blood) is another hallmark symptom that should raise suspicion for lung malignancy.

Systemic signs such as unexplained weight loss and fatigue become more pronounced as the cancer advances. Wheezing might be noted when tumors narrow air passages. If NSCLC spreads to other parts of the body (metastasis), additional symptoms can appear—bone pain in cases of skeletal involvement or headaches, confusion, or seizures if the brain is affected.

Because of the nonspecific nature of these symptoms, especially in early stages, individuals at risk—particularly smokers or those with a history of lung disease—should seek prompt evaluation if such signs persist.

Is There a Role for Screening in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer?

Yes, screening plays a crucial role in the early detection and management of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), particularly in individuals at high risk. NSCLC often progresses silently, and many patients are diagnosed at advanced stages when curative treatment becomes more challenging. Early detection through screening has been shown to significantly reduce mortality and improve outcomes.

The primary tool for NSCLC screening is low-dose computed tomography (LDCT). The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) provided robust evidence that LDCT screening can lead to a 20% reduction in lung cancer-specific mortality in high-risk populations, such as individuals aged 55 to 74 years with at least a 30-pack-year smoking history, who are current smokers or have quit within the past 15 years (National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, 2011). These findings have been further supported by the NELSON trial in Europe, which also demonstrated a mortality benefit, particularly among men (de Koning et al., 2020).

As a result, major organizations such as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend annual LDCT screening for high-risk individuals. The updated USPSTF guidelines (2021) now suggest screening for adults aged 50 to 80 years with a 20 pack-year smoking history (USPSTF, 2021), while NCCN guidelines also emphasize risk-based eligibility criteria (Wood et al., 2022).

However, LDCT screening is not without limitations. False positives, overdiagnosis, and cumulative radiation exposure are potential concerns. Nevertheless, when implemented appropriately, the benefits—especially detecting tumors at an early, potentially curable stage—far outweigh the risks. Screening enables timely surgical intervention, targeted therapies, and overall better patient prognosis (Mazzone et al., 2021).

Read More About SUMMIT Study on Oncodaily

Risk Factors for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) arises from complex interactions between environmental exposures, lifestyle choices, and genetic predisposition. The most prominent risk factor is tobacco smoking, which accounts for approximately 80–90% of lung cancer cases. Carcinogens in cigarette smoke induce genetic mutations that promote malignant transformation of respiratory epithelial cells (Jemal et al., 2008). Secondhand smoke exposure also contributes significantly, especially among individuals who live with smokers or are exposed in workplace environments over long periods (Thun et al., 2013).

Occupational and environmental exposures are notable contributors as well. Prolonged exposure to substances such as asbestos, arsenic, radon gas, diesel exhaust, chromium, and nickel compounds is associated with a higher incidence of NSCLC. Radon, a naturally occurring radioactive gas, is the second leading cause of lung cancer in the United States and is particularly significant in non-smokers (Field, 2001). Air pollution, particularly fine particulate matter (PM2.5), has been identified as a risk factor for lung cancer, especially in urban areas with high vehicular and industrial emissions. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies outdoor air pollution and particulate matter as Group 1 carcinogens (IARC, 2013).

Genetic susceptibility also plays a role. Individuals with a family history of lung cancer may have inherited genetic variations in DNA repair mechanisms or carcinogen metabolism that increase their risk (Amos et al., 2008). Moreover, pre-existing lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), and pulmonary tuberculosis have been linked with elevated NSCLC risk, likely due to chronic inflammation and tissue damage (Turner et al., 2007). Lastly, age and gender influence risk. The likelihood of NSCLC increases with age, and while historically more common in men due to higher smoking rates, incidence among women—particularly non-smokers—has been rising (Travis et al., 2015).

Read About Myths and Reality on Oncodaily

What Lifestyle Changes Can Decrease the Risk of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer?

Lifestyle modifications play a crucial role in reducing the risk of developing non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The most effective change is smoking cessation. Avoiding tobacco in all forms—both active smoking and secondhand smoke exposure—significantly lowers the risk of NSCLC. Quitting smoking at any age provides substantial health benefits, including a reduction in lung cancer risk over time (Jemal et al., 2008). Minimizing exposure to environmental carcinogens such as radon gas, asbestos, and industrial pollutants is another critical preventive step. Regular testing for radon in homes, especially in high-risk geographic areas, and using appropriate protective measures in occupational settings can decrease exposure to known lung carcinogens (Field, 2001).

A nutrient-rich diet that includes fruits, vegetables, and foods high in antioxidants may support lung health and reduce oxidative stress, although this should not replace the primary preventive value of avoiding tobacco (Willett, 2002). Regular physical activity contributes to overall immune function and may reduce chronic inflammation, a factor in many cancers, including lung cancer (Lee et al., 2012). Limiting alcohol consumption, managing chronic respiratory conditions like COPD, and maintaining a healthy body weight are additional ways to reduce systemic inflammation and improve respiratory health.

Lastly, early screening in high-risk individuals (e.g., long-term smokers aged 50–80) through low-dose CT scans is a proactive lifestyle decision that facilitates early detection and improves survival outcomes (National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, 2011).

Prognosis of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

The prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) varies widely depending on several factors, including the stage at diagnosis, tumor histology, molecular subtype, patient performance status, and response to treatment. Overall, NSCLC tends to have a better prognosis than small cell lung cancer, especially when diagnosed early. Patients diagnosed with stage I NSCLC who undergo complete surgical resection can have 5-year survival rates exceeding 70%, especially in the absence of nodal involvement (Goldstraw et al., 2016).

However, as the disease progresses to more advanced stages, survival rates decline significantly. For stage IV (metastatic) NSCLC, the 5-year survival rate is typically below 10%, although this has been improving in recent years with the introduction of targeted therapies and immunotherapies (Hirsch et al., 2017). The presence of actionable mutations such as EGFR, ALK, or ROS1 can significantly improve outcomes when targeted therapies are used. These therapies have demonstrated extended progression-free survival and improved quality of life compared to standard chemotherapy (Camidge et al., 2019).

Additionally, PD-L1 expression may guide the use of immunotherapy, which has shown survival benefits in advanced NSCLC, particularly in tumors with high PD-L1 expression levels (Reck et al., 2016). Prognosis is also influenced by general health and comorbidities. Patients with a good performance status (ECOG 0–1) typically respond better to treatment and experience longer survival.

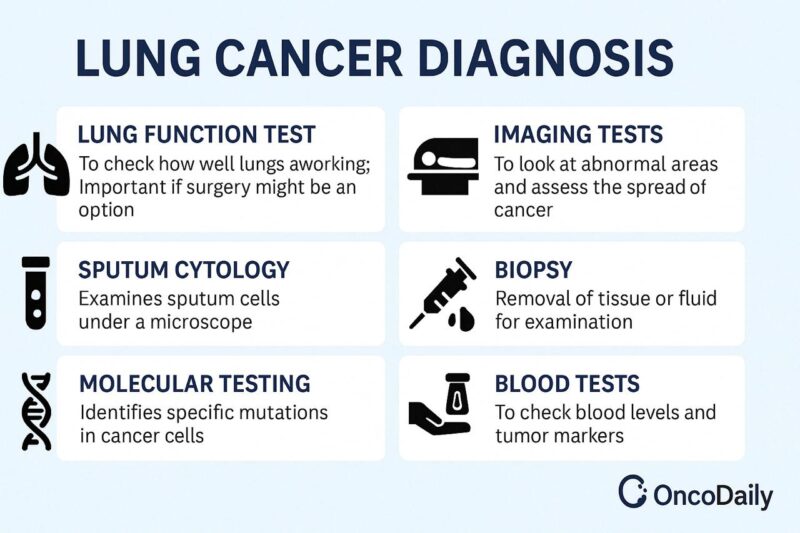

Diagnosis of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Diagnosing non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) involves a multi-step process that includes clinical evaluation, imaging, tissue biopsy, and molecular testing. This comprehensive approach helps confirm malignancy, classify tumor subtype, determine stage, and identify molecular targets for treatment.

Initial Evaluation: Diagnosis often begins when patients present with respiratory symptoms such as persistent cough, hemoptysis, chest pain, or dyspnea. However, many NSCLC cases are discovered incidentally through imaging for unrelated issues (Ettinger et al., 2022).

Imaging Studies: Imaging plays a central role in the diagnosis, staging, and treatment planning of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). It helps determine the location, size, extent of the tumor, and possible spread to lymph nodes or distant organs.

- Chest X-ray is commonly the first imaging test but may miss small or early-stage tumors.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest is the preferred imaging modality, providing detailed visualization of the tumor, lymph nodes, and possible metastases.

- Positron emission tomography (PET-CT) is used to evaluate metabolic activity of the tumor and detect distant metastases, often assisting in staging.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is performed if there are neurological symptoms or in advanced cases to assess for brain metastases.

Tissue Diagnosis: A definitive diagnosis requires histologic confirmation through a tissue biopsy. Techniques vary based on tumor location and include:

- Bronchoscopy with biopsy for centrally located tumors

- CT-guided needle biopsy for peripheral lesions

- Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) for sampling mediastinal lymph nodes

- Surgical biopsy (e.g., video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or mediastinoscopy) in select cases

Histologic Classification: Once tissue is obtained, it is examined under a microscope to determine the specific histologic subtype: adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or large cell carcinoma.

Molecular and Biomarker Testing: Molecular profiling is essential in NSCLC, particularly for patients with non-squamous histology. Testing includes:

- EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF, KRAS mutations

- PD-L1 expression levels

- NTRK, RET, and MET alterations in advanced cases

These biomarkers help determine eligibility for targeted therapies or immunotherapy.

Treatment Overview for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

The treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) varies based on the stage of the disease, histological subtype, presence of molecular mutations, and the overall health status of the patient. NSCLC is typically treated using a multimodal approach that includes surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy.

In early-stage NSCLC (Stage I and some Stage II tumors), surgical resection, typically via lobectomy, is the treatment of choice. Surgical management often results in favorable outcomes, especially when complete resection is achieved and the tumor has not metastasized. Adjuvant chemotherapy may be offered for high-risk Stage IB and Stage II patients to improve survival (Goldstraw et al., 2016).

For patients who are not surgical candidates due to comorbidities or poor pulmonary reserve, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) is considered an effective curative alternative. SBRT has demonstrated comparable local control rates to surgery in selected patient populations (Chang et al., 2015).

Read More About Radiotherapy for Lung Cancer on Oncodaily

In locally advanced NSCLC (Stage III), concurrent chemoradiotherapy is the standard approach. Patients with unresectable Stage IIIA or IIIB disease often receive platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with radiation therapy. The addition of durvalumab as consolidation therapy after chemoradiation has become the standard of care following the PACIFIC trial, which demonstrated improved progression-free and overall survival (Antonia et al., 2018).

In advanced or metastatic NSCLC (Stage IV), systemic therapy is the primary treatment. The advent of molecular profiling has revolutionized the treatment landscape. Patients with driver mutations—such as EGFR mutations, ALK rearrangements, ROS1 fusions, and BRAF V600E—are treated with targeted therapies. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) like osimertinib, and ALK inhibitors like alectinib, have shown superior outcomes compared to chemotherapy in their respective subgroups (Paz-Ares et al., 2020; Peters et al., 2017).

Read More About Immunotherpy for Lung Cancer on Oncodaily

For patients without targetable mutations, immune checkpoint inhibitors have become the mainstay. PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors such as pembrolizumab and atezolizumab, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy, have demonstrated significant survival benefits. The choice of immunotherapy depends on PD-L1 expression levels, tumor burden, and patient performance status (Reck et al., 2016).

In all stages, supportive care including pain management, pulmonary rehabilitation, and psychological support is essential. Palliative radiotherapy may also be offered for symptom control in metastatic settings. Ongoing research is focusing on refining treatment algorithms using biomarkers, resistance mechanisms, and combination regimens.

Revolutionary Advances in NSCLC Treatment: Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy

The management of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has undergone a paradigm shift with the introduction of targeted therapy and immunotherapy, drastically altering survival outcomes and offering personalized treatment options. Targeted therapies, specifically tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), are used in patients whose tumors harbor actionable mutations. For instance, patients with EGFR mutations benefit from third-generation TKIs such as osimertinib. In the ADAURA trial, adjuvant osimertinib significantly prolonged disease-free survival compared to placebo in patients with resected stage IB–IIIA EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Likewise, in the FLAURA trial, osimertinib showed a median overall survival of 38.6 months, compared to 31.8 months with first-generation TKIs, establishing it as the standard of care in the metastatic setting (Wu et al., 2020).

For ALK-rearranged NSCLC, newer-generation ALK inhibitors like alectinib and lorlatinib have shown superior efficacy over crizotinib. The ALEX trial demonstrated that alectinib extended progression-free survival to 34.8 months, significantly delaying disease progression and central nervous system (CNS) metastases (Peters et al., 2017). Lorlatinib, evaluated in the CROWN trial, further improved CNS control, with high intracranial response rates and sustained progression-free survival benefits, offering new hope for long-term disease control in ALK-positive patients (Solomon et al., 2021).

In parallel, immunotherapy has emerged as a cornerstone of treatment in advanced NSCLC, particularly for tumors with high PD-L1 expression. The PACIFIC trial set a new standard in unresectable stage III NSCLC by demonstrating that consolidation durvalumab after chemoradiation improved median overall survival to 47.5 months, compared to 29.1 months in the placebo arm (Antonia et al., 2018). In the metastatic setting, the KEYNOTE-024 trial established pembrolizumab as first-line therapy for PD-L1 ≥50% NSCLC, showing a median overall survival of 30 months, compared to 14.2 months with chemotherapy alone (Reck et al., 2016).

Additionally, combination regimens of immunotherapy with chemotherapy have enhanced outcomes for a broader population. The KEYNOTE-189 study in non-squamous NSCLC and KEYNOTE-407 in squamous NSCLC confirmed that pembrolizumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy significantly improved OS compared to chemotherapy alone, regardless of PD-L1 expression. These findings underscore the transformative role of immune checkpoint inhibitors in frontline therapy.

Read About Imumunotherapy on Oncodaily

Together, these breakthroughs have redefined the standard of care in NSCLC, highlighting the importance of molecular testing and biomarker-guided therapy. As newer agents and combinations are explored in ongoing clinical trials, the focus continues to shift toward durable remission, quality of life, and potential cure for subsets of NSCLC patients.

Novel 2025 Therapies and Ongoing Clinical Trials in NSCLC

As of 2025, the treatment landscape for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) continues to evolve with the development of targeted therapies, immune modulators, and innovative platforms such as mRNA vaccines. These strategies aim to enhance tumor control, prolong survival, and minimize toxicity by tailoring treatment to molecular and immune profiles.

Ivonescimab (AK112) is a novel bispecific antibody targeting both PD-1 and VEGF-A. This dual mechanism aims to both re-engage T-cell activity and inhibit tumor angiogenesis, effectively combining immunotherapy and anti-angiogenesis in one molecule. Preliminary data from Phase I/II studies have shown promising anti-tumor activity in pretreated NSCLC patients (Li et al., 2024).

EMPOWER-Lung 1 Trial: Cemiplimab Demonstrates Durable 5-Year Survival Benefit in Advanced NSCLC with High PD-L1 Expression.The Phase 3 EMPOWER-Lung 1 trial has provided compelling 5-year data on cemiplimab (Libtayo) as a first-line monotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients exhibiting PD-L1 expression ≥50% and lacking EGFR, ALK, or ROS1 aberrations. In this study, cemiplimab significantly improved overall survival (OS) compared to chemotherapy, with a median OS of 26.1 months versus 13.3 months, respectively. The 5-year OS probability stood at 29.0% for cemiplimab-treated patients, nearly doubling the 15.0% observed in the chemotherapy group (Kilickap et al., 2025).

Notably, patients with PD-L1 expression ≥90% experienced the most pronounced benefits, achieving a median OS of 39 months and a 5-year OS probability of 40% (Baramidze et al., 2025). The safety profile of cemiplimab remained consistent with earlier analyses, with fewer grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events compared to chemotherapy (Kilickap et al., 2025).

Read More About Cemiplimab on Oncodaily

THIO (6-thio-2’-deoxyguanosine) is a telomerase-targeting compound that induces telomere dysfunction and apoptosis selectively in cancer cells. Currently in clinical trials in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors, THIO has shown early signals of efficacy in NSCLC patients resistant to prior immunotherapy (Heidel et al., 2024).

BNT116, an mRNA-based therapeutic vaccine developed by BioNTech, is designed to trigger antigen-specific immune responses against NSCLC. It is undergoing early-phase trials both as monotherapy and in combination with checkpoint inhibitors, showing strong immunogenicity and early tumor shrinkage in a subset of patients (Müller et al., 2025).

Other investigational treatments include novel KRAS G12D and EGFR exon 20 inhibitors, ADCs (antibody-drug conjugates) targeting HER3 and TROP2, and multi-kinase inhibitors for patients with MET amplification or RET rearrangements. Several of these have demonstrated objective response rates exceeding 30% in early studies and are now in Phase II or III trials (Jensen et al., 2025; Sharma et al., 2024).

The incorporation of these agents into clinical protocols reflects a paradigm shift toward precision oncology, where treatment selection is driven by the tumor’s genomic landscape. These ongoing efforts underscore the dynamic nature of NSCLC management and hold potential to significantly improve long-term survival.

You Can Watch More on OncoDaily Youtube TV

Written by Armen Gevorgyan, MD

FAQ

What is non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

NSCLC is the most common type of lung cancer, accounting for about 85% of cases. It includes subtypes like adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma.

What are the main symptoms of NSCLC?

Common symptoms include a persistent cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, coughing up blood, fatigue, and unexplained weight loss.

What causes NSCLC?

Major risk factors are smoking, exposure to secondhand smoke, radon gas, asbestos, air pollution, and genetic predisposition.

How is NSCLC diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves imaging tests like chest X-rays and CT scans, followed by a biopsy to confirm the presence of cancer cells.

What are the stages of NSCLC?

NSCLC is staged from I to IV, with Stage I being localized and Stage IV indicating that cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

What treatment options are available for NSCLC?

Treatment may include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, depending on the stage and specific characteristics of the cancer.

Can NSCLC be cured?

Early-stage NSCLC can often be treated successfully, potentially leading to a cure. Advanced stages are less likely to be curable but may be managed to prolong life and improve quality of life.

What is the prognosis for someone with NSCLC?

Prognosis varies based on the stage at diagnosis, overall health, and response to treatment. Early detection generally leads to a better outcome.

Are there any new advancements in NSCLC treatment?

Recent advancements include targeted therapies and immunotherapies that are tailored to specific genetic mutations in cancer cells, offering more effective and personalized treatment options.

How can I reduce my risk of developing NSCLC?

Avoiding smoking, reducing exposure to known carcinogens, maintaining a healthy lifestyle, and undergoing regular health check-ups can help lower the risk.