What is pheochromocytoma?

Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma are rare neuroendocrine tumors that arise from chromaffin cells, which are responsible for the production of catecholamines such as epinephrine and norepinephrine. These tumors can cause significant health issues due to the excessive secretion of these hormones, leading to symptoms such as high blood pressure, headaches, and palpitations. Although pheochromocytomas are more commonly diagnosed in adults, they can also occur in children, accounting for about 10-20% of cases.

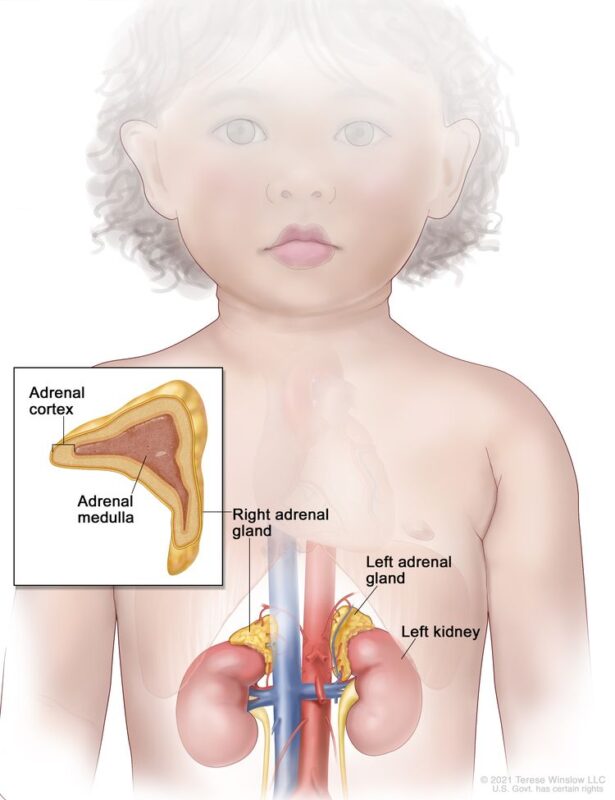

The image is taken from the National Cancer Institute website.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The average age at diagnosis for pediatric pheochromocytoma is between 11 and 13 years, with boys being affected approximately twice as often as girls. A significant proportion of pediatric pheochromocytomas are associated with hereditary syndromes. Up to 80% of pediatric cases have a genetic mutation, which is higher than the prevalence in adults. The most common genetic mutations include von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome, Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2 (MEN2), Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1), and Succinate Dehydrogenase (SDH) mutations, including SDHB, SDHD, SDHC, and SDHA.

Pheochromocytomas typically arise in the adrenal medulla, while paragangliomas can occur in extra-adrenal locations such as the sympathetic and parasympathetic ganglia. Pediatric pheochromocytomas often exhibit a noradrenergic or dopaminergic phenotype, which is more common in children compared to adults. The frequency of bilateral tumors is higher in children than in adults (20% vs 5-10%), while that of malignant tumors is lower (3.5% vs 3-14%). More than one-third of affected children have multiple tumors, most of which are recurrent. In children, 70% of cases are unilateral, 70% are confined to adrenal locations, and an increased association with familial syndromes is noted. In 30-40% of children with pheochromocytomas, tumors are found in both adrenal and extra-adrenal areas or in only extra-adrenal areas.

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause of pheochromocytoma is not fully understood, but research has identified several risk factors and potential contributing factors:

Genetic Factors

Approximately 25-35% of pheochromocytoma cases are linked to hereditary conditions. The most common genetic syndromes associated with pediatric pheochromocytoma include:

- Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease: A genetic disorder characterized by the formation of tumors and cysts in different parts of the body.

- Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia (MEN) syndromes: Particularly MEN type 2, which involves tumors in multiple endocrine glands.

- Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1): A condition that causes tumors to form on nerve tissue.

- Succinate Dehydrogenase (SDH) mutations: These include SDHB, SDHC, SDHD (mutations in these genes disrupt the function of the succinate dehydrogenase enzyme, leading to an accumulation of cellular signals that promote tumor growth), and other related mutations, which are associated with a higher risk of malignancy.

Sporadic Cases

In cases where no genetic link is identified, pheochromocytoma occurs sporadically. The exact cause of these sporadic tumors is not well understood, but they are believed to arise from random genetic mutations within the chromaffin cells.

Prognosis

The overall survival rates for pediatric pheochromocytoma are generally favorable, especially when the tumor is detected early and treated effectively.

Impact of Genetic Mutations

Genetic mutations significantly influence the prognosis of pediatric pheochromocytoma. As already mentioned approximately 80% of pediatric cases are associated with germline mutations in susceptibility genes such as VHL, SDHB, SDHD, and NF1. The presence of these mutations can affect the long-term prognosis and the risk of recurrence or malignancy.

- VHL Mutations: Patients with VHL mutations often have multiple and bilateral tumors. Despite this, the overall prognosis remains relatively good with appropriate management.

- SDHB Mutations: These mutations are linked to a more aggressive disease course, including a higher risk of malignancy and recurrence. Patients with SDHB mutations require more intensive follow-up due to the increased risk of metastatic disease.

Recurrence and Long-Term Follow-Up

Recurrence is a significant concern, particularly in cases with genetic mutations. Studies indicate that the recurrence rate can increase over time, reaching up to 50% at 30 years post-diagnosis. Long-term follow-up is essential for early detection of recurrent or new tumors, especially in hereditary cases.

- Nonmetastatic Recurrence: The risk of nonmetastatic recurrence is around 25% at 10 years, increasing to 50% by 30 years. Regular monitoring through biochemical testing and imaging is crucial.

- Malignant Recurrence: Malignant pheochromocytomas, though rare in children, have a poorer prognosis. The five-year survival rate for malignant pheochromocytomas is approximately 40%. Long-term follow-up and aggressive management are necessary.

Factors Influencing Prognosis

Several factors influence the prognosis, including tumor size, age at diagnosis, and extent of surgical resection. Larger tumors (≥8 cm) are associated with a higher risk of recurrence and metastasis. Younger age at diagnosis is linked to a higher risk of recurrence, particularly in patients with SDHB mutations. Complete surgical resection is critical for favorable outcomes, as incomplete resection is associated with a higher risk of recurrence and poorer prognosis.

Symptoms

The symptoms of pheochromocytoma in children can vary but are primarily related to the excessive production of catecholamines. Common symptoms include:

- High blood pressure (hypertension): This is the most common symptom and can be severe.

- Headaches: Often associated with high blood pressure.

- Sweating: Excessive sweating, particularly during hypertensive episodes.

- Pallor: Pale skin due to vasoconstriction.

- Palpitations: Rapid or irregular heartbeats.

- Dizziness: Often related to blood pressure fluctuations.

- Nausea and vomiting: Gastrointestinal symptoms can occur.

- Abdominal pain: Pain or bloating in the belly.

- Weight loss: Despite a good appetite, children may not gain weight appropriately.

Diagnosis

Clinical Evaluation

Diagnosis begins with a thorough clinical evaluation, including a detailed medical history and physical examination. The healthcare provider will inquire about the child’s symptoms and any family history of related genetic conditions.

Biochemical Tests

Biochemical testing is crucial for diagnosing pheochromocytoma. The most sensitive tests include:

- Plasma free metanephrines and normetanephrines: These are metabolites of catecholamines and are highly sensitive indicators of pheochromocytoma.

- 24-hour urinary catecholamines and metanephrines: This test measures the levels of catecholamines and their metabolites in the urine over a 24-hour period.

Imaging Studies

Imaging studies are used to locate the tumor and assess its extent. Common imaging modalities include:

- Ultrasound: Often used as an initial imaging test.

- Computed Tomography (CT) scan: Provides detailed images of the adrenal glands and surrounding structures.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Useful for detailed imaging and in cases where radiation exposure should be minimized.

- 123I-Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy: A specialized scan that helps to identify pheochromocytoma and any metastatic lesions.

Genetic Testing

Given the high prevalence of hereditary pheochromocytoma, genetic testing is recommended for all pediatric patients. Identifying specific genetic mutations can guide treatment and inform family members about their risk.

This video by the Pheo Para Alliance explains pheochromocytoma to children.

Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is the primary treatment for pediatric pheochromocytoma and is often curative. The goal is to completely remove the tumor, which can be achieved through various surgical techniques:

- Laparoscopic Adrenalectomy: This minimally invasive procedure uses small incisions and specialized instruments to remove the tumor. It is associated with shorter hospital stays and quicker recovery times. A study reported successful laparoscopic partial adrenalectomy in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease, with no mortalities during the study period.

- Open Adrenalectomy: This approach is used for larger tumors or when laparoscopic surgery is not feasible. It involves a larger incision and a longer recovery period.

Preoperative Management

Before surgery, it is crucial to manage blood pressure and other symptoms to reduce surgical risks. This typically involves:

- Alpha-Blockers: Medications such as phenoxybenzamine are used to block the effects of catecholamines on blood vessels, helping to control blood pressure.

- Beta-Blockers: These are used to manage heart rate and prevent arrhythmias, often administered after alpha-blockade is established.

- Tyrosine Hydroxylase Inhibitors: These can reduce catecholamine production and are sometimes used in preparation for surgery.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is used for patients with metastatic pheochromocytoma or when the tumor cannot be completely removed surgically. Common chemotherapeutic regimens include:

- Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, and Dacarbazine (CVD): This combination has shown effectiveness in reducing tumor size and controlling symptoms.

- Gemcitabine and Docetaxel: Another combination used for metastatic disease, which has shown some positive responses.

Radiopharmaceutical Therapy

- High-dose iodine I 131-labeled metaiodobenzylguanidine (131I-MIBG) therapy is used for metastatic pheochromocytoma. This treatment involves using a radioactive compound that targets and destroys tumor cells. Responses to 131I-MIBG therapy have been documented, providing symptomatic relief and sometimes reducing tumor size.

Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapies are increasingly used for treating metastatic pheochromocytoma. These include:

- Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs): Sunitinib and cabozantinib are examples of TKIs that have shown promising results in treating metastatic pheochromocytoma, although they are not formally approved for this indication.

- mTOR Inhibitors: These are used in certain cases to inhibit tumor growth.

Immunotherapy

- Immunotherapy is an emerging treatment option for pheochromocytoma. It involves using the body’s immune system to target and destroy cancer cells. Clinical trials are ongoing to evaluate the effectiveness of various immunotherapeutic agents in treating pheochromocytoma.

Radiotherapy

- External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) are used in specific cases, particularly for metastatic or inoperable tumors. SBRT allows high doses of radiation to be delivered precisely to the tumor, minimizing damage to surrounding tissues.

The treatment of pediatric pheochromocytoma involves a multidisciplinary approach, including surgery, preoperative management, chemotherapy, radiopharmaceutical therapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and radiotherapy. Early detection and comprehensive management are crucial for improving outcomes and quality of life for affected children. Ongoing research and clinical trials continue to advance the treatment options available for this rare but significant condition.

More information about completed and ongoing clinical trials for immunotherapy can be found here – clinicaltrials.gov.

Patient’s Survivorship

Survivorship in pediatric pheochromocytoma involves long-term monitoring and management due to the risk of recurrence and potential complications from the disease and its treatment. The prognosis for children with pheochromocytoma is generally favorable, especially with early detection and effective treatment.

Long-term Follow-up

Long-term follow-up is essential for the early detection of recurrent or new tumors. This includes regular biochemical testing and imaging studies. Genetic counseling is also recommended for patients and their families to understand their risk and manage it appropriately. The European-American-Pheochromocytoma-Paraganglioma-Registry study highlighted that a second primary paraganglial tumor developed in 38% of patients, with the frequency increasing over time, reaching 50% at 30 years after the initial diagnosis.

Quality of Life

Managing the long-term effects of pheochromocytoma and its treatment is crucial for maintaining a good quality of life. This includes addressing any psychological impacts, such as anxiety or depression, and providing support for any physical limitations that may result from the disease or its treatment.

Problems During and After Treatment

- Hypertension: Persistent hypertension can be a significant issue both before and after treatment. It is essential to manage blood pressure effectively to prevent complications such as heart damage or stroke. This may involve ongoing medication and lifestyle modifications.

- Recurrence: The risk of tumor recurrence necessitates regular follow-up and monitoring. Patients should be educated about the signs and symptoms of recurrence and the importance of adhering to follow-up appointments and testing schedules.

- Psychological Support: The diagnosis and treatment of pheochromocytoma can be stressful for both patients and their families. Access to psychological support and counseling can help manage anxiety, depression, and other emotional challenges associated with the disease.

- Genetic Counseling: Given the hereditary nature of many pheochromocytoma cases, genetic counseling is crucial. This helps patients and their families understand their risk, make informed decisions about genetic testing, and manage any identified genetic conditions.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Patients may need to make lifestyle changes to manage their condition effectively. This includes maintaining a healthy diet, engaging in regular physical activity, and avoiding triggers that can exacerbate symptoms, such as certain foods or stress.

Managing Specific Complications

- Postoperative Hypotension: Postoperative hypotension is a common issue due to the sudden drop in catecholamine levels after tumor removal. This can be managed with intravenous fluids and careful monitoring of blood pressure.

- Hypoglycemia: Severe hypoglycemia can occur following tumor removal due to the rapid fall of circulating catecholamines and an increase in insulin secretion. Regular blood glucose monitoring and appropriate titration of dextrose infusions are recommended.

- Adrenal Insufficiency: Patients who undergo bilateral adrenalectomy will require lifelong steroid replacement therapy to manage adrenal insufficiency. Steroid supplementation is rarely required otherwise.

Future Perspectives of Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric Pheochromocytoma

Diagnosis

- Genetic Testing: Advances in genetic testing and identification of new susceptibility genes will enhance early detection and personalized treatment strategies.

- Biomarkers: Research on novel biomarkers, such as circulating tumor cells and cell-free tumor DNA, aims to improve early detection and monitoring.

Treatment

- Targeted Therapies: Development of targeted therapies, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors shows promise for treating metastatic or inoperable cases.

- Immunotherapy: Ongoing clinical trials are evaluating the efficacy of immunotherapeutic agents, such as checkpoint inhibitors, in treating pheochromocytoma.

- Novel Radiopharmaceuticals: New radiopharmaceuticals aim to deliver targeted radiation to tumor cells while minimizing damage to healthy tissues.

- Combination Therapies: Personalized treatment approaches combining surgery, radiotherapy, and targeted therapies based on the tumor’s genetic and molecular profile are being explored.

Conclusion

Pediatric pheochromocytoma, though rare, is a potentially curable cause of secondary hypertension in children. Advances in genetic testing, imaging techniques, and targeted therapies have significantly improved the diagnosis and treatment of this condition. Early detection and a multidisciplinary approach involving endocrinologists, surgeons, genetic counselors, and other specialists are crucial for optimal outcomes. With ongoing research and improved management strategies, the prognosis for children with pheochromocytoma continues to improve, offering hope for a healthy and fulfilling life.

Sources

- Childhood Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma – National Cancer Institute

- Adrenal Tumors – The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

- Pheochromocytoma in Children – Stanford Medicine Children’s Health

- Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma – American Society of Clinical Oncology

- Review of Pediatric Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma – Frontiers in Pediatrics

- Pediatric Metastatic Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis, Genetics, and Therapeutic Approaches – Frontiers in Endocrinology