What if some of the most promising anticancer strategies were already sitting in pharmacies worldwide, inexpensive, and decades old?

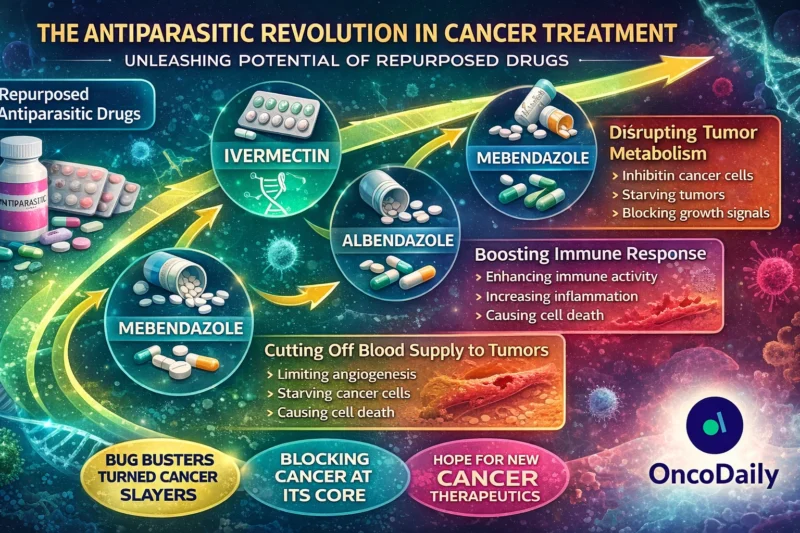

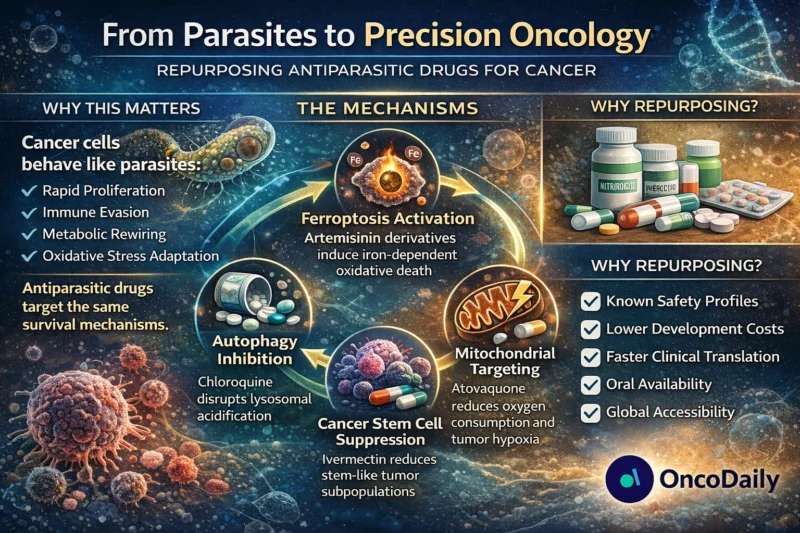

Drug repurposing is no longer a fringe idea. In oncology, where timelines are long and attrition rates are brutal, repositioning approved agents offers a strategic shortcut. Antiparasitic drugs: macrolides, benzimidazoles, artemisinin derivatives, and quinolines, have emerged as unexpected candidates in this movement. The biological logic is compelling: parasites and cancer cells share hallmarks such as immune evasion, metabolic reprogramming, rapid proliferation, and stress adaptation (Arora et al., 2019; van Tong et al., 2017).

But is this just mechanistic curiosity, or a clinically actionable frontier?

Why Antiparasitic Drugs Make Biological Sense in Cancer

Cancer cells rewire metabolism, suppress immunity, resist apoptosis, and exploit oxidative stress pathways. Many antiparasitic agents evolved to exploit similar vulnerabilities in helminths and protozoa. Shared targets include tubulin, mitochondrial respiration, CDKs, STAT3, and autophagy machinery (Dorosti et al., 2014).

Importantly, drug repositioning reduces early-phase uncertainty because pharmacokinetics and safety profiles are already characterized (Ashburn & Thor, 2004). This dramatically lowers development costs and accelerates translation, critical in an era of escalating oncology expenditures.

By 2026, over 300 active oncology trials globally include at least one repurposed non-oncology drug, and antiparasitics represent a growing subset in combination strategies with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and radiotherapy.

Let’s examine the evidence class by class.

Ivermectin and the Macrolides: From River Blindness to Cancer Stem Cells

Ivermectin (IVM), a macrocyclic lactone widely used for onchocerciasis, has demonstrated multi-target anticancer activity.

Mechanistically, ivermectin induces mitochondrial apoptosis by increasing Bax/Bcl-2 ratios and activating caspase cascades (Zhang et al., 2019). It suppresses EIF4A3-dependent RNA splicing in ovarian cancer (Li & Zhan, 2020), inhibits TMEM16A chloride channels linked to tumorigenesis (Zhang et al., 2020), and disrupts the PAK1–AKT–mTOR axis, triggering autophagic cell death (Dou et al., 2016).

Of particular relevance in 2026 is ivermectin’s activity against cancer stem-like cells (CSCs). Studies demonstrate selective inhibition of CD44⁺/CD24⁻ breast cancer subpopulations and downregulation of NANOG, SOX2, and POU5F1 (Dominguez-Gomez et al., 2018). Given the persistent challenge of minimal residual disease, this CSC-selective toxicity is strategically important.

Recent translational work (2023–2025) has focused on ivermectin in combination regimens. Preclinical models show synergy with platinum agents and endocrine therapy via suppression of EGFR/ERK/Akt/NF-κB signaling (Jiang et al., 2019). Early phase I trials in solid tumors have explored dose escalation strategies with manageable toxicity profiles, though definitive phase II data remain pending as of 2026.

The challenge is pharmacodynamic optimization. Tumor microenvironments differ significantly from parasitic niches, and achieving therapeutic intratumoral concentrations without systemic toxicity remains a central question.

Read About Ivermectin and Immunotherapy on OncoDaily io

Benzimidazoles: Tubulin Disruption and Metabolic Collapse

Albendazole (ABZ) and flubendazole (FLU) exemplify benzimidazole repurposing.

Albendazole disrupts microtubule polymerization, induces mitotic arrest, and inhibits glucose uptake via the GLUT1/AMPK/p53 axis (Liu et al., 2020). It suppresses HIF-1α protein expression under hypoxic conditions, impairing glycolytic adaptation and angiogenesis (Pourgholami et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2017).

Given that hypoxia drives therapeutic resistance (Cairns et al., 2011), HIF-1α suppression is clinically meaningful. A phase I study in refractory solid tumors established 1,200 mg twice daily (14 days on, 7 days off) as a tolerable schedule, with tumor marker reductions observed in a subset of patients (Pourgholami et al., 2010). Although objective responses were limited, disease stabilization suggested biologic activity.

Flubendazole extends this paradigm by targeting STAT3 and inducing autophagy-dependent apoptosis (Lin et al., 2019). Notably, it reduces PD-1 expression and myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) accumulation in melanoma models (Li et al., 2019), hinting at immunomodulatory potential.

By 2026, small-molecule PD-1 pathway modulation remains an active research area because monoclonal antibodies are costly and intravenous-only (Li & Tian, 2019). Flubendazole’s oral availability positions it uniquely within this space.

Artemisinin and Ferroptosis: Iron as a Therapeutic Lever

Artemisinin derivatives (ARTs), including dihydroartemisinin (DHA) and artesunate (ART), represent perhaps the most mechanistically exciting class.

Their endoperoxide bridge reacts with intracellular iron to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing oxidative stress, DNA damage, and apoptosis (Trachootham et al., 2009; Mercer et al., 2011). Molecular docking studies show inhibition of topoisomerase I (Kadioglu et al., 2017), while artemisitene destabilizes c-Myc via NEDD4-mediated degradation (Chen et al., 2018).

However, the 2020s brought a major conceptual shift: ferroptosis.

Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent non-apoptotic cell death pathway, is regulated by GPX4 and intracellular iron homeostasis (Dixon et al., 2012; Stockwell et al., 2017). Artemisinin derivatives sensitize tumor cells to ferroptosis by modulating iron regulatory proteins (IRP1/IRP2) and destabilizing ferritin complexes (Chen et al., 2020; Ooko et al., 2015).

This is not trivial. Resistance to apoptosis defines advanced malignancy. Ferroptosis bypasses many apoptosis-resistant mechanisms. In pancreatic and glioma models, artesunate-induced ferroptosis was modulated by GRP78 and HSPA5 feedback loops (Wang et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2019), opening opportunities for combinatorial inhibition strategies.

Clinically, a phase I trial of intravenous artesunate in advanced solid tumors demonstrated acceptable tolerability with a disease control rate of 27% (Deeken et al., 2018). By 2026, additional basket-style phase II studies are investigating artesunate in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors, particularly in KRAS-mutant pancreatic cancer and triple-negative breast cancer.

The ferroptosis–immunogenic cell death axis is now a central research focus.

Quinolines: Autophagy, Hypoxia, and Mitochondrial Reprogramming

Chloroquine (CQ) remains the most extensively studied quinoline in oncology. As a lysosomotropic agent, it inhibits autophagic flux by increasing lysosomal pH (Amaravadi et al., 2011; Pasquier, 2016). Autophagy inhibition enhances chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity and may increase tumor immunogenicity (Zamame et al., 2020).

However, clinical results have been mixed. Phase I trials combining chloroquine with temozolomide in glioblastoma demonstrated safety but limited survival advantage (Compter et al., 2020). Small sample sizes and heterogeneity complicate interpretation.

Atovaquone (ATV), a mitochondrial complex III inhibitor, represents a different paradigm. By reducing oxygen consumption rates, atovaquone alleviates tumor hypoxia (Ashton et al., 2016). This improves radiotherapy sensitivity, a critical advantage in hypoxic tumors.

Additionally, atovaquone inhibits mitochondrial STAT3 signaling and selectively targets oxidative phosphorylation-dependent cancer stem cells (Xiang et al., 2016; Fiorillo et al., 2016). Given the renewed emphasis on metabolic targeting in oncology (Ashton et al., 2018), atovaquone’s repositioning has gained momentum.

In 2024–2026, translational trials explored atovaquone as a radiosensitizer in non-small cell lung cancer and head-and-neck cancers, leveraging hypoxia modification strategies.

The Hard Truth: Why Aren’t These Drugs Standard of Care?

Despite promising preclinical data, few antiparasitic drugs have reached definitive phase III oncology trials.

Key barriers include:

- Pharmacokinetic limitations in tumor microenvironments.

- Suboptimal dosing paradigms, antiparasitic doses may not match anticancer requirements.

- Lack of commercial incentive for off-patent agents.

- Complex mechanistic pleiotropy, complicating biomarker-driven trial design.

- Potential pro-tumor effects under stress adaptation, such as NF-κB activation (Vlahopoulos, 2017).

Nanotechnology and targeted delivery platforms are addressing some of these limitations. Nanocarrier systems have improved albendazole bioavailability in xenograft models (Hettiarachchi et al., 2016), while ferroptosis-enhancing nanoformulations amplify artemisinin activity (Guo et al., 2020).

2026 Perspective: Emerging Research Directions in Drug Repurposing

By 2026, research into antiparasitic drug repurposing has evolved from exploratory observations to mechanistically focused investigation. The emphasis is increasingly placed on defined biological targets, rational combinations, and biomarker-guided patient selection. Current research directions include ferroptosis induction strategies guided by iron metabolism markers, cancer stem cell–selective mitochondrial targeting, modulation of autophagy within immunotherapy combinations, and hypoxia correction to enhance radiotherapy sensitivity.

Importantly, antiparasitic drugs are not approved for cancer treatment. Their use in oncology remains investigational and is limited to preclinical models and clinical trials. While mechanistic data are compelling, regulatory approval for cancer drugs requires rigorous multi-phase clinical development, including phase I safety trials, randomized phase II efficacy signals, and confirmatory phase III studies demonstrating survival benefit or clinically meaningful endpoints.

The oncology drug approval process, overseen by agencies such as the FDA and EMA—demands robust evidence of safety, efficacy, manufacturing quality, and reproducibility. Many repurposed agents face additional challenges, including lack of commercial sponsorship, funding barriers for large randomized trials, and the need for optimized dosing strategies distinct from their original antiparasitic indications.

Drug repurposing does not replace innovation, nor does it bypass regulatory standards. Rather, it represents a parallel research pathway. In a landscape where resistance mechanisms evolve rapidly and drug development timelines remain long, revisiting established pharmacologic agents through contemporary molecular frameworks may expand therapeutic possibilities, but only if supported by high-quality clinical evidence.

The transition from laboratory promise to approved oncology therapy remains complex. Whether antiparasitic agents ultimately earn a defined place in cancer treatment will depend not on theoretical plausibility alone, but on rigorous, well-designed clinical trials.

Written by Armen Gevorgyan, MD