Jeffrey Bluestone’s beginning wasn’t a grand plan. It was an undergraduate opportunity at Rutgers University and one professor who changed his trajectory.

“I had a chance to do a senior project with a professor there, Robert Cousins,” he said. “It was a transformative experience for me.”

For the first time, he got to “dig down” into a deep scientific problem and feel what it means to discover something that isn’t yet understood.

“At the time, this was in nutrition and how molecules bound to metals,” he said. “It actually turned out it was calmodulin when they finally discovered what it was.”

But the real origin wasn’t calmodulin. It was curiosity.

“It really started as… this inquisitiveness of trying to understand things we just didn’t understand.”

Even then, he knew he wanted the questions to matter to human health. That drew him first into virology, graduate school at Rutgers, and then into cancer immunology at the Sloan Kettering.

Cancer immunology, before the world believed

He entered the field at a time when the immune system and cancer were not yet married in the public imagination.

“This was back in the day when people didn’t have a lot of confidence that the immune system would be able to tackle cancer,” he said.

At Sloan Kettering, he worked with “a guy named Bob Good,” one of the early giants of immunology.

“He was really one of the first cancer immunologists,” Bluestone said, “and… had gotten his start discovering the cause of bubble babies”, the immunodeficiency that revealed foundational truths about the immune system.

Then came the National Cancer Institute, still with cancer in mind, but his path shifted again.

Immune tolerance

At the NCI, he got “sidetracked into organ transplantation.” Not because he abandoned cancer, but because cancer immunology was still, in his words, a black box.

“Cancer was a real black box at the time. We knew very little about what it meant to be an antigen… something that a T cell would recognize in a tumor.”

Transplantation, by contrast, gave him a clean experimental moment.

“In organ transplantation it was very straightforward,” he said. “You knew when the tissue was going in… you had a good idea of what was being recognized; the major histocompatibility complex.”

For him, it was a way to dissect fundamentals: the mechanism of antigen recognition, rules that cancer would eventually need, too.

From there, his road kept winding: University of Chicago into autoimmune disease, while still staying connected to cancer; work touching checkpoint biology and CD28; then UCSF, where he ran a lab for 25 years.

Along the way, he also became a builder of platforms: leading or helping shape major consortiums—the Immune Tolerance Network, the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, and others. And about five years ago, he moved into company-building to translate academic work into a product.

When he looked back across the whole arc, cancer → transplant → cancer → autoimmunity, he named the throughline clearly:

“The common theme throughout all of it was immune tolerance,” he said. “How do you induce it and how do you break it?”

“Understanding the rules,” he added, “and how to develop drugs based on that was really key.”

The three-line mantra on his wall

When I asked what was key to his success, he didn’t romanticize it.

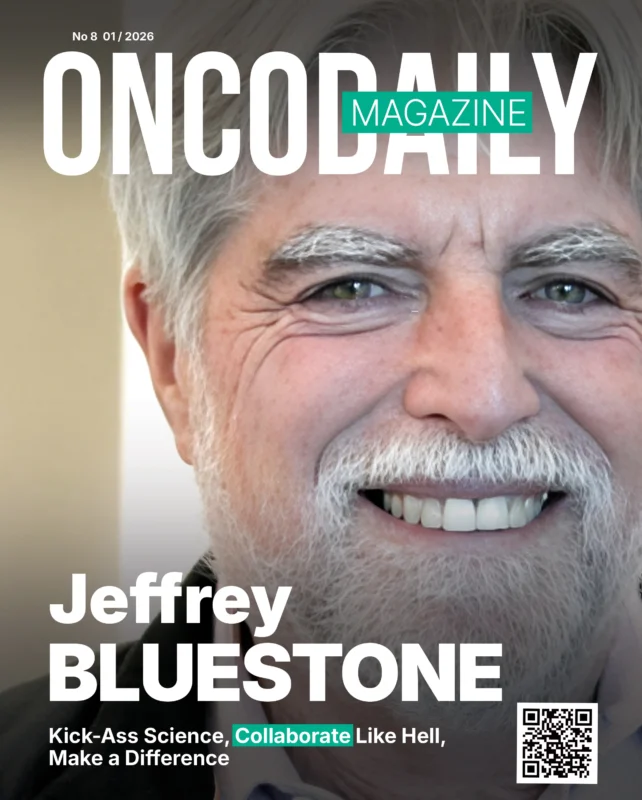

“I always say there are three things… written on the wall here,” he said.

First: “Kick-ass science.”

For him, it starts with impact. Do science that matters. Do it rigorously.

Second: “Collaborate like hell.”

He spoke about collaboration not as a slogan, but as a practice: sharing reagents, sharing tools, giving people what they need to move faster together.

Then he told a story that belongs in the folklore of immunology: the night he chose generosity over secrecy.

“We made the first anti-mouse CD3 antibody,” he said, work that ultimately contributed to the development of a human anti-CD3 approach in type 1 diabetes.

He remembered a Gordon Conference in 1985, when he was young. The sessions ran late, later and later, until he was the final speaker at 10 p.m.

“In those days, we had slide projectors.”

When his turn finally came, he didn’t run a full data deck. He instructed the projectionist to load one slide.

“It was my name and address.”

And then he told the room:

“We’ve made an anti-CD3 antibody. I’m sure a lot of you will want it. So here’s my name and address. Just write me.”

“I think I sent it out to a couple hundred people after that,” he said.

Third: a purpose beyond curiosity.

“The last is sort of a commitment to make a difference.”

Not just difference in publications, but difference in lives:

“Either in a student’s life or in a patient’s lives or in a colleague’s life.”

“Just follow your nose.”

“Frank sat me in his office,” Jeffrey remembered his mentor Frank Fitch from the University of Chicago., “and he said, we can sit here and we can negotiate a deal… down to the penny… But in the end, you need to do what you want to do.”

Then Dr. Fitch gave him a line that Jeffrey Bluestone carried like a rule of life:

“Whatever the bottom line number is, ignore what you budgeted. Just follow your nose. Do what you think is going to be important.”

Dr. Bluestone paired that with another inheritance: “honesty and transparency.”

“I’ve tried to build my career on being as honest and transparent as possible.”

Trying to win by hiding, he added, is a misunderstanding of how science truly moves.

“Frank was the ultimate honest gentleman from the Midwest,” he said. “Just a good guy.”

The people: “the most important thing in my career”

When I asked about mentees, he didn’t hesitate on scale.

“I’ve had over 100 students and postdocs.”

He spoke with visible pride, less about his own achievements than about theirs: professors, department heads, leaders in academia and industry.

He named some specifically: “My first postdoc, Rafi Hirsch, is now head of pediatrics at UCSF. A graduate student early on, Randy Cron, is head of the Department of Pediatric Rheumatology at University of Alabama, Birmingham.”

He could have gone on “for 20 minutes,” but his point was simple:

“There’s no doubt that the most important thing in my career has been to train, mentor, and help facilitate other people’s growth.”

Jeff Bluestone with trainees at PICI opening

“being a pretty good salesman”

I asked about a common belief: that to be a successful scientist, you must devote yourself entirely to science, and everything else will suffer. Bluestone answered with humor first.

“You don’t want to talk to my wife or my kids,” he said. “It would not come off well.”

But then he explained how he made multiple roles coherent: he didn’t treat them as different identities. He treated them as different stages of the same mission.

If “doing great science” is your north star, leadership becomes about enabling that science through recruiting, support, and culture.

Collaboration scales too: it works in a lab, in a department, in a university.

And then he named something many scientists avoid saying out loud:

“I’ve benefited from being a pretty good salesman,” he said.

In science, “sales” sounds dirty. But he reframed it as storytelling, the ability to articulate why something matters.

“Whether it’s a group of eighth graders or graduate students or the funding agencies, you’ve got to be able to tell your story.”

He argued that this is one of the weaknesses of modern science: in an era where “anti-science has become so common,” many scientists don’t know how to communicate clearly, simply, and compellingly.

And he gave an example: why a basic discovery like restriction enzymes matters.

“It led to the cloning of insulin, which helps hundreds of millions of people.”

“I think I’ve been pretty good at storytelling,” he added.

How to talk about science: make it simple, make it human

When I asked what he’d teach others about “sales,” he returned to a communication principle:

“Make it simple.”

He offered a metric:

“If you can’t tell your story” to “a science major in high school,” he said, “then you’re going to have trouble.”

He described a course he taught with Frank Fitch: immunology for non-science majors. On the first day, he’d provoke the room with questions anchored in real life:

“My daughter has chickenpox. Should I be here teaching you today?”

“Which is more concerning to you, herpes or HIV?”

The point wasn’t drama. It was relevance.

“We have to keep it simple,” he said. “We have to keep it interesting. We have to tap into people’s lives.”

And for grants, philanthropy, and fundraising: help people understand “the opportunity, the value, and the difference it can make.”

Building teams: “a very high bar”

Asked how he selected people, he admitted he was “a little bit tougher” than he’d be today.

He remembered his own postdoc interview with David Sachs, being sent to the blackboard immediately to explain mouse genetics.

He carried a similar standard forward:

“A very high bar” for being smart, being an effective communicator, and being committed and passionate.

And he noted, without arrogance, that he has “overwhelmingly been lucky” in the choices he made.

The Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy: the sandbox model

Sean Parker arrived with conviction. He had read deeply, traveled, studied the field.

“He said, ‘I am committed to cancer immunotherapy,’” Bluestone recalled.

Sue Desmond-Hellmann, then chancellor at UCSF, coming from Genentech, “an amazing leader”, pressed him on other approaches. Parker’s answer stayed fixed.

“Nope,” he said. “Immunology. It’s going to be immunology.”

Desmond-Hellmann brought Parker to Bluestone.

“We sat down and probably talked for five or six hours.”

Then they designed the model to match Bluestone’s core mantra: best science, collaboration, difference.

Best science meant going where the best science lived, bringing in people like Carl June, Jim Allison, Lewis Lanier, Toni Ribas, and others.

But collaboration needed structure. So Bluestone describes what they built as a “sandbox.”

“This was our sandbox. It had walls. Not everybody could be in the sandbox.”

But if you were inside, the institute would provide the tools, “sand toys”, to accelerate work: bioinformatics, clinical trials capability, infrastructure.

Then came the retreats: not fly-in talks, but real convenings.

Sean Parker made them attractive on purpose – great locations, families welcome, business-class travel, so people would stay the whole time.

And because the room was full of serious peers, people brought their best, even unpublished.

“They’d show their best science… when it was just early days,” Jeffrey Bluestone remembered.

The retreats became “a magnet” for ideas, collaborations, and momentum.

Parker also insisted on something else: don’t stop at the bench. Translate outward, into patients and into the world.

He built infrastructure for university IP access and company formation. PICI, Bluestone noted, has formed “a dozen plus” companies.

“It’s worked very well over the last 10 years, allowing real impact despite being small compared to big pharma.”

Working with Sean Parker

Was it easy to work with Parker?

“It’s always easier to work with really smart people,” Jeffrey Bluestone said. “And he’s a really smart person.”

He laughed about the cost:

“Did I have to take calls sometime at two or three in the morning because he’d have an idea and call me up? Yeah.”

But he emphasized Parker’s unusual depth for a philanthropist: not just funding, but intellectual engagement.

“Sean and I would spend hours talking about the science,” he said. “He’d read the papers… go to figure three.”

“Sometimes his eyes were bigger than my stomach,” Dr. Bluestone added, ideas bigger than capacity, but “for the most part, it was fantastic.”

Jeff Bluestone with Sean Parker

The next decade of the Parker Institute

Looking forward, he described a renewal after a difficult period. During COVID, after Bluestone left, there was no CEO replacement, and convening became hard.

But recently, leadership stabilized:

They brought in CEO Karen Knudsen (formerly head of the American Cancer Society), a highly accomplished and well-known leader, and recruited Ira Mellman as the President.

“There’s no better cancer immunologist and scientist than Ira,” he said.

He described a new strategic plan as “very exciting,” and noted Sean Parker remains “very, very engaged.”

Advice to young scientists: hang in there and widen your map

Dr. Bluestone didn’t sugarcoat the moment.

“It is a very difficult time right now,” he said. “I have tremendous empathy for young people trying to get into the field.”

Financial constraints, visas, and the public perception of science…

But his advice:

“Hang in there.”

“Continue finding ways to continue their training.”

“Be willing to use their voices in support of science.”

And he offered a reframing from his own recent experience building a company:

“Science can be done in a variety of different settings,” he said.

Universities. Small biotech. Big pharma.

“If you have the right people and you have the right commitments… you can do great science anywhere.”

“So don’t start out with any preconceived notion that there’s only one way, to do the science that matters.”

“It took 35 years from the time I made the drug till the time it was approved.”

When I asked what story resonated most across his career, he went to a long journey: the effort to develop an immunotherapy for type 1 diabetes with his colleague Kevan Herold.

Meeting families changed him.

“Everyone says, ‘Oh, diabetes… you take insulin… you’re fine.’ Well, the answer is no,” he said. “It’s a terrible disease.”

He described hearing parents’ stories, understanding how devastating it is for families, and how that reinforced why the work mattered.

He also learned the brutal truth of translation:

“It took 35 years from the time I made the drug till the time it was approved.”

And in the process, he saw that barriers are not only scientific.

“It doesn’t matter necessarily whether the drug works,” he said. “Is it… economics? Infrastructure? Screening?”

For him, the lasting lesson was resilience.

“You need to be resilient… persistent… committed, because you’re going to get a lot of things… constantly putting barriers in your way.”

What he’s building now: living drugs with regulatory T cells

Jeffrey Bluestone’s current focus is Sonoma Biotherapeutics, a company grown out of UCSF work with Qizhi Tang, built on foundational biology from pioneers like Fred Ramsdell and Sasha Rudensky, centered on regulatory T cells.

Regulatory T cells, he said, are “the kingpin” of peripheral tolerance.

“They surveil the body. They look for autoimmune or inflammation and they shut it down.”

He has believed since the early 2000s that these cells could become therapeutics. Instead of a small molecule or biologic, he chose the hardest path:

“We decided to go big,” he said. “We decided we were going to build a cell therapy.”

The strategy: isolate Tregs, expand them, and, at Sonoma Bio, engineer them with genes to make them antigen-specific, then return them to patients so they home to the right tissue and regulate inflammation locally.

He shared a key milestone: a first trial in rheumatoid arthritis presented at the American College of Rheumatology, showing “very significant clinical effects.”

He’s aiming for something bigger than a single indication:

“A new modality,” he said, “living drugs.”

“How do we create long-term tolerance,” he asked, “without having to retreat with drugs every week, month or so?”

“I’m very excited about where Sonoma Bio is right now,” he added.

Sonoma People

It all was about people

On reading, he remembered Lewis Thomas, former president of Sloan Kettering, whose books captured the inner life of being a scientist.

“He was a tremendous communicator.”

And he recalled one vivid scene: sitting on the lawn in Quebec, engaged to his future wife, studying a biology text (Lewin) because prelims were coming.

On family, he described a “middle class” upbringing with “a lot of love” and “a lot of strength.” His mother died young, heart disease in her early 50s. His father worked as a dry cleaner, and Bluestone spent Saturdays helping, mopping floors, learning people.

“It all was about people,” he said.

He remembered employees who had migrated from the South to New Jersey, some even living with his family, and a father who could diffuse conflict with calm service:

“You didn’t like the way your pants were pressed? We’ll do it again. Don’t worry!”

Interview by Gevorg Tamamyan, Editor-in-Chief of OncoDaily