Inside Valentina Prevolnik Rupel’s Mission to Make Health Equal for All.

The second cover story of World Health Voices features Professor Valentina Prevolnik Rupel, Minister of Health of Slovenia — a distinguished health economist and academic leader whose evidence-based approach and commitment to health system reform have made her one of Europe’s most respected voices in public health policy. In this insightful conversation on World Health Voices, she reflects on the evolving challenges of healthcare systems, the role of solidarity and innovation in shaping sustainable health models, and Slovenia’s vision for a healthier, more equitable future.

“Change is always difficult by itself—and nobody wants to accept it. That’s why we build arguments, evidence, and trust.”

Professor Valentina Prevolnik Rupel, Minister of Health of Slovenia, speaks with the calm assurance of someone who has seen the health system from every angle: researcher, policymaker, economist, and now reformer. Her journey has been guided by one principle—to make every health decision grounded in data, fairness, and dialogue.

Choosing Healthcare: “A Complex System Worth Understanding”

“I’m an economist by profession,” she begins, “and when I had to choose my specialization for my master’s and PhD, healthcare fascinated me.”

It was the early 1990s, and few economists were working in health policy in Slovenia. “At that time, economists in healthcare were mostly accountants or cost analysts,” she recalls. “But very few dealt with healthcare policy. I saw an open space—and I thought this is where I can make a difference.”

Her decision was pioneering. “I believe I was the first economist in Slovenia to choose healthcare as a dedicated field,” she says with quiet pride.

Because health economics was not yet developed in Slovenia, she studied abroad in the UK. “I wanted to understand healthcare as a complex system—one that requires broad understanding but is also full of economic challenges: how to invest in quality of care, how to manage risks that rising costs bring, and how to still ensure equitable access for everyone. That’s what drew me in.”

A Career Built Across Every Corner of the System

After graduating from the Faculty of Economics, she joined the Institute for Economic Research, where she helped establish healthcare as a policy area within its strong social policy department.

“There were researchers working on pensions and social care, but healthcare was open,” she explains. “So I started my master’s and PhD on how to allocate resources to optimize healthcare for patients.”

Her early work connected her to the EuroQol Foundation, which developed the EQ-5D instrument for measuring health-related quality of life—now a global standard. “Those collaborations shaped my entire career,” she says.

Her experience spans every side of the system: research at the Institute for Economic Research, payer side at the National Health Insurance Institute, policy and regulation at the Ministry of Health.

“I’ve been fortunate to see healthcare from every perspective—provider, payer, regulator, and researcher,” she says. “That’s a real asset. For 25 years, I’ve worked with all the stakeholders. It teaches you how differently they see the same policy—and how important it is to listen.”

The Leadership Principle: Listening and Evidence

If she had to name the key to her success, she would say it in one word: listening.

“For me, it’s very important that people feel they can share their views on the healthcare system with me,” she explains. “We may not always agree, but every point of view matters if it’s supported by data and arguments.”

She believes most decisions can and should be based on evidence. “There are areas where we don’t have perfect data, but in most cases, there is sufficient evidence to guide us. I try to build policy through dialogue with stakeholders—providers, professional organizations, patient groups, and society.”

That participatory approach, she says, is deeply Slovenian. “We are a country that values social participation. We try to involve everyone—social partners, professionals, and patients—in shaping measures. That’s how reforms gain acceptance.”

From Vision to Action

Professor Prevolnik Rupel became Minister of Health in October 2022, marking two years in office this fall. “It’s not such a long time,” she says modestly. “But these two years have been very full.”

Even with decades of experience, the transition to leading the entire system brought surprises. “You realize how many things you never knew,” she smiles. “It’s quite challenging.”

Her focus, from day one, has been clear: accessibility and quality.

“I wanted to make sure patients can access care more easily, and that once they do, that care meets a defined standard of quality.”

Her proudest legislative milestone is the Act on Quality Assurance in Healthcare, which established Slovenia’s first independent agency for quality and safety.

“This agency now manages quality indicators, safety procedures, reporting of adverse events, and health technology assessment,” she explains. “Before, each hospital had its own efforts, but without national coordination, indicators were inconsistent and not comparable. Now, we can collect data systematically, compare performance, and exchange good practices. That’s a real step forward.”

She also highlights significant reforms in financing and workforce policy.

“This year, we upgraded the payment systems across acute care, specialist services, and primary care,” she says. “We worked to align prices with actual costs, so that providers make decisions based on patient needs, not on which services are more profitable. That’s crucial for fairness and sustainability.”

The Ongoing Challenges

Even with progress, challenges remain. “Healthcare systems are never static—they evolve constantly,” she says. “There are always new discoveries, new technologies, changing demographics.”

Human resources remain her greatest concern. “The whole of Europe is struggling with workforce shortages. The demographic structure is shifting, and we must adapt to ensure sustainability.”

Yet her tone is pragmatic, not pessimistic. “Challenges are part of the process,” she says. “You can’t fix everything at once—but you can move forward with evidence, dialogue, and conviction.”

Cancer Care in Slovenia: “We Have Doubled Incidence but Reduced Mortality”

When asked about the state of cancer care in Slovenia, she begins with precision. “Cancer care in Slovenia has developed significantly over the past two decades,” she says.

The challenge, she explains, is demographic. “Cancer incidence has doubled over the last 20 years, increasing by about 1.7% annually. That’s largely because Slovenia has one of the oldest populations in the European Union. Older populations are more susceptible to cancer.”

But what stands out is the country’s progress despite that trend. “Between 2011 and 2021, cancer mortality declined by 15% in men and 13% in women. Slovenia outperformed many EU countries in reducing both overall and avoidable cancer mortality. For breast and colorectal cancer, avoidable deaths were cut in half compared to EU averages.”

She attributes this success to “effective and timely healthcare interventions” and a well-structured National Cancer Control Program.

“This program covers prevention—reducing smoking, alcohol use, stress, promoting healthy diet and physical activity—and it includes three national screening programs: for breast, colorectal, and cervical cancer,” she says.

Participation is exceptionally high. “We are the first country in the EU in attendance for these screening programs,” she notes. “It’s because of our proactive approach to inviting citizens to participate.”

The National Cancer Control Program, she adds, “is fully aligned with the EU’s Beating Cancer Plan and built with strong involvement from civil society. We make sure patients’ perspectives are included in care planning.”

Balancing Innovation and Value

As one of Europe’s leading experts on value-based healthcare, Professor Prevolnik Rupel speaks with realism about the economic pressures driving oncology today.

“Costs always rise—and they will continue to rise because innovation is moving fast,” she says. “Our task is to balance innovation and affordability while ensuring equitable access to treatment for everyone.”

Slovenia’s universal health coverage, which includes more than 99% of the population, adds both opportunity and responsibility. “We have to make sure that every euro spent brings the highest possible value,” she says. “That means building stronger data systems, linking databases, and measuring not just costs but outcomes that matter to patients.”

She references WHO estimates that 20–30% of healthcare services provide no meaningful value to patients. “That’s where we must focus—to eliminate waste, improve efficiency, and redirect resources where they make a real difference.”

Her vision is simple but demanding: “We must move from process and structure indicators to outcome indicators. For too long, healthcare has measured what is easy to count, not what truly matters to patients. If we align outcomes with costs, we can maintain innovation and sustainability at the same time.”

The EU Perspective: Slovenia as a Model of Data and Dialogue

“Cancer is one of Slovenia’s top priorities,” she says. “Our Cancer Registry is one of the oldest in Europe, and that gives us strong data to guide policy. Every year, we analyze the numbers, evaluate our measures, and adjust our strategies.”

She believes small countries can play a large role in Europe’s healthcare transformation. “With a population of two million, Slovenia can serve as a pilot country—a testing ground for new investments and technologies. Once proven, those solutions can be scaled to other countries.”

Her broader vision for Europe centers on digital collaboration. “We need strong digital infrastructure and interoperability between systems to exchange data and best practices more effectively. That’s how Europe can grow together.”

Artificial Intelligence: Promise and Caution

When the conversation turns to AI and digital medicine, her tone balances excitement with responsibility.

“It’s an area we’re all hopeful about—but also a little afraid,” she admits. “Artificial intelligence must be built on good data. Bad input will always produce bad output, no matter how advanced the algorithm.”

She sees enormous potential. “In cancer, AI can transform early detection, diagnostic precision, personalized treatment planning, and remote patient monitoring,” she says. “In Slovenia, we’re already preparing for this future in cooperation with our Ministry of Science.”

Recently, her ministry conducted a national survey among developers of AI solutions. “We asked where they see the greatest opportunities—and nearly half of the proposals were in healthcare. There were 52 ideas for immediate implementation, from automated speech and scheduling systems to diagnostic tools.”

But she insists that the transformation must remain ethical and transparent. “We need good data, good legislation, and moral clarity. AI offers services too valuable to stop, but we must maintain control over where development goes.”

Her words carry both conviction and warning. “We have to protect the ethics of AI now—before it’s too late.”

“No One Should Be Left Behind”

“Healthcare must not depend on your income, where you live, or whether you once had cancer. Everyone deserves equal access — to care, to dignity, to life.” With that conviction, Professor Valentina Prevolnik Rupel, Minister of Health of Slovenia, continues to redefine how an economist can humanize health policy.

Equity is not an abstract concept for her — it’s a measurable goal. “I am proud that Slovenia ranks first in the European Cancer Screening Policy Index,” she says. “We remain fully committed to sustaining these programs, and we are already exploring new screening programs for lung and prostate cancer.”

Financial protection is central to Slovenia’s approach. “All cancer care is covered by compulsory health insurance for more than 99% of our population,” she explains. “Even those who are unemployed, homeless, or migrants are covered. The less than 1% not included are usually in transition between statuses — for example, after graduation and before finding employment.”

But she is quick to emphasize that coverage alone is not enough. “Education plays a major role. We know there are differences in healthcare access based on education level. That’s why we passed the Strategy for Health Literacy, to increase understanding among both citizens and healthcare providers.”

The initiative, she explains, involves partnerships with NGOs and patient organizations to “identify and overcome barriers” to health access.

She proudly highlights another milestone: “One of the key goals in Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan was to ensure fair access for people with a history of cancer to financial and insurance products. In Slovenia, we achieved that last year by passing the ‘Right to Be Forgotten’ law. Now, people who have recovered from cancer have equal access to loans and insurance as everyone else. That’s what equity means — not just in healthcare, but in life.”

Mentors Who Shaped Her Path

When asked about mentors, her answer is immediate — and heartfelt. “There are two people who really shaped my professional journey,” she says.

“The first is Professor Tine Stanovnik, who was my PhD mentor. He taught me so much about public finance, taxation, and the structure of health funding.”

“The second is Dr. Dorijan Marušič, a cardiologist who continues to advise me at the Ministry of Health. He helped me understand the medical side of health policy — something that’s difficult to learn if you’re not a clinician. I’m deeply grateful to both.”

Books and Inspiration

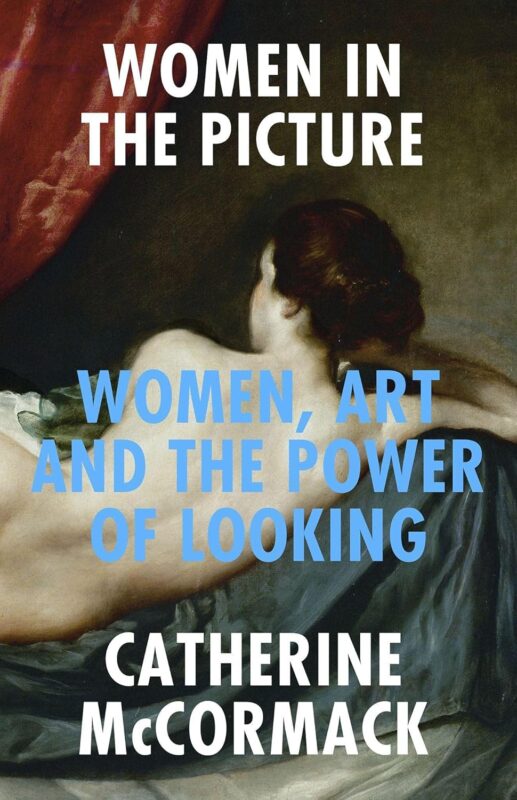

Though her schedule leaves little time for leisure reading, she smiles when the topic turns to books. “I love reading, especially before bed,” she says. “Right now, I’m re-reading Women in the Picture by Catherine McCormack. It’s about gender equality — how women have been represented by artists compared to men. It’s a wonderful, thought-provoking book, and I recommend it to everyone.”

Advice for the Next Generation

When asked what she would tell young people aspiring to lead in healthcare, her message is clear and encouraging.

“I would tell them — go for it!” she says. “Healthcare policy is a fascinating and meaningful area, but we need more young people in it. It’s important to gain a broad perspective — to understand how the system works from different sides — and to always base decisions on data, not assumptions.”

“Stay Positive, Stay Curious”

Asked to describe herself in one sentence, she pauses briefly, then answers with characteristic precision:

“I am result-oriented, curious, and I always try to stay positive.”

That combination — rigor, curiosity, and optimism — defines both her leadership and her outlook on reform.

“We Learn Most by Listening”

And who does she believe should be next in this series of world health voices? She smiles. “I would recommend my friend Professor Elly Stolk from Erasmus University in Rotterdam,” she says. “She is an expert on quality in healthcare, and I always enjoy our conversations. You’ll love talking to her.”

As the conversation closes, her final words summarize her philosophy — data-driven, inclusive, and human:

“Healthcare reform begins with listening — to patients, to professionals, to data. Only then can we build systems that are both efficient and fair.”

Interview by Gevorg Tamamyan, Editor-in-Chief of OncoDaily