Fabio Ynoe de Moraes, Associate Professor at Queen’s University, shared a post on LinkedIn:

“This Sunday, the tennis world will turn its eyes to Centre Court for the 2025 Wimbledon men’s final, where Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz—the two defining talents of the post–Big Three era—will face off in a match that is already being hailed as a battle for the new order.

But beyond the spectacle, this anticipated clash symbolizes a deeper transformation: in modern tennis, as in modern oncology, dominance is no longer driven by raw talent alone, but by the convergence of data, adaptability, and systems-level excellence.

A Three-Decade Transformation: Wimbledon (1992–2024)

From 1992 to 2024, Wimbledon crowned just 9 different men’s singles champions over 33 editions. Three of them—Pete Sampras (7), Roger Federer (8), and Novak Djokovic (7)—accounted for 22 of those titles (66.7%), establishing an unprecedented concentration of dominance in modern sports.

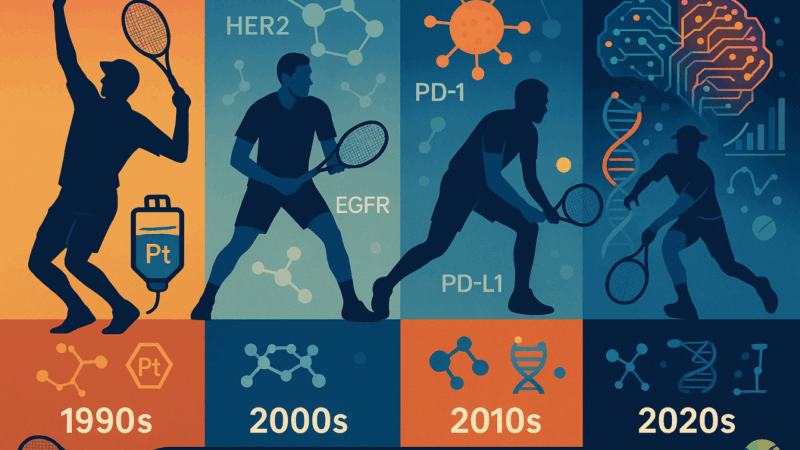

This era can be divided into four distinct performance paradigms:

Travel back to the 1990s, and you’d find Pete Sampras prowling the grass courts with a serve so thunderous it seemed to crack the very air. His lightning‑fast volleys and acrobatic net rushes epitomized the serve‑and‑volley era, where matches were won in a handful of explosive rallies lasting barely a dozen strokes. Surfaces rewarded slice attacks and crisp timeliness, producing short, surface‑based points that left audiences in awe of raw power and precision.

By the turn of the millennium, Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal ushered in a new all‑court hybrid. Federer’s silky footwork and Nadal’s topspin artillery forced rallies to stretch—and grasses to slow—demanding greater adaptability. The once rapid-fire exchanges gave way to longer duels, as advances in racket technology amplified both power and spin. Suddenly, mastery meant blending offense and defense across every surface, rewiring the sport’s tactical blueprint.

The 2010s belonged to Novak Djokovic, whose relentless baseline mastery redefined endurance. He combined peak physical conditioning with an ironclad mental resolve—products of sports science breakthroughs and meticulous training regimens—to outlast opponents in marathon rallies. The baseline became the new battlefield, and every forehand and backhand was executed under the microscope of sports physiology and psychology.

Today, in the 2020s, a generational shift has brought Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz to the fore with an integrated model of tactical agility and biomechanical optimization. They fuse the serving prowess of the ’90s, the all‑court craft of the 2000s, and the stamina of the 2010s into a seamless whole.

Their game is a testament to the sport’s evolution: fluid movement guided by data‑driven training, every shot calibrated for maximum efficiency, and a hunger to push boundaries both on and off the court. In their hands, tennis is no longer a test of one singular style—but a dynamic synthesis of past innovations and future potential.

Average champion age rose from 24.4 years in the 2000s to 29.3 in the 2010s, reflecting improvements in recovery, injury prevention, and longevity—key features of high-performance ecosystems.

Oncology in Parallel: From Cytotoxics to AI-Driven Precision

This same trajectory of escalating complexity, performance, and integration can be traced in oncology’s evolution:

Travel back to the 1990s and you’ll find oncology in its “Chemotherapy Era,” where cytotoxic agents ruled supreme. Platinum salts like cisplatin and carboplatin became the backbone of treatment, their DNA–crosslinking prowess unleashing unprecedented response rates in lung, ovarian and head‑and‑neck cancers. Early taxanes—paclitaxel and docetaxel—followed, exploiting microtubule stabilization to arrest dividing cells. This era was defined by an empirical, dose‑intense philosophy: maximize cell kill, manage toxicity, and hope the therapeutic window holds.

By the 2000s, the arrival of “Targeted Therapy” transformed that blunt‑force approach into molecular precision. Monoclonal antibodies and small‑molecule inhibitors began to intercept the very signals that drove cancer growth. Trastuzumab’s blockade of HER2 in breast cancer and imatinib’s revolution in chronic myeloid leukemia proved the concept: dial down a specific oncogenic pathway, ruin the cancer’s playbook, and spare normal tissues. EGFR inhibitors (gefitinib, erlotinib) and VEGF antagonists (bevacizumab) extended this paradigm, ushering in a more deliberate, mechanism‑based treatment philosophy.

The 2010s then erupted with the “Immunotherapy Era,” reframing cancer as a disease of immune evasion rather than solely one of unchecked growth. Checkpoint inhibitors like anti–PD‑1 (nivolumab, pembrolizumab) and anti–PD‑L1 (atezolizumab) jolted T‑cells back to life, producing durable remissions in melanoma, lung and beyond. CAR‑T cell therapies—engineered to recognize CD19 in B‑cell malignancies—underscored the power of personalized, living drugs.

Combination strategies melded immunomodulators with chemo or targeted agents, heralding an age in which harnessing the host defense became as critical as attacking the tumor directly.

Now, in the 2020s, we stand at the threshold of “Systems Oncology,” an integrated, adaptive approach that leverages multi‑omics profiling, real‑world evidence and AI‑driven decision support. Tumor genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics converge with clinical phenotypes to create dynamic risk models. Machine‑learning algorithms sift through electronic health records and population registries, suggesting personalized regimens in real time.

Adaptive trial designs—umbrella, basket and platform studies—allow rapid iteration: drop ineffective arms, add promising new drugs, all within the same protocol. In this era, the old dichotomy between research and practice dissolves, replaced by a continuous learning health system where each patient’s journey informs the next.

Both fields transitioned from individual performance to systemic orchestration. As in tennis—where success now requires not just athleticism, but nutritionists, biomechanists, data analysts, and mental coaches—oncology demands multidisciplinary, real-time, data-informed approaches.

Selectivity and the Rise of Elite Ecosystems

Between 2003 and 2022, only 4 players—Federer, Nadal, Djokovic, Murray—won Wimbledon. That’s 20 titles across 4 individuals (90.9%). Similarly, between 2011 and 2022, over 70% of FDA oncology drug approvals came from a small set of dominant sponsors, often using selective endpoints like PFS or ORR in narrowly defined patient populations.

In both cases, we see the rise of a highly selective approaches: success is increasingly gated by access to data, capital, infrastructure, and execution at the margins.

Conclusion: The Convergence Era

The 2025 Sinner–Alcaraz final is not just a match — it is a metaphor. Just as the future of tennis lies in hybridization, adaptability, and strategic precision, the future of oncology lies in intelligent integration, where biology, technology, and decision-making converge.”

More posts featuring Fabio Ynoe de Moraes.