Douglas Flora, Executive Medical Director of Yung Family Cancer Center at St. Elizabeth Healthcare, President-Elect of the Association of Cancer Care Centers, and Editor in Chief of AI in Precision Oncology, shared a post on LinkedIn:

”Why Time Doesn’t Heal All Wounds – But it Does Make Them Bearable

We talk a lot – and I write a lot – about how AI will give us back time. Time to diagnose faster, time to reduce admin, time to be more efficient. That part is vital. But why do we want that time back?

It’s not just to see more patients. It’s so we can perform the essential, irreplaceable human work of medicine: sitting in the dark caves of grief with our patients and their families.

I wrote today about the one question that has haunted me throughout my career: “Will this pain ever go away?”

The answer is complex, and it comes down to a powerful analogy called “the ball in the box.” This concept helped me understand how we carry the losses – not only those of our patients, but the losses we accumulate ourselves over decades of practice. It explains why the pain doesn’t diminish in intensity, only in frequency, and why that is a sign of healing, not failure.

This work – the human work – is what sustains us. It’s the critical ingredient AI can never provide.

If you are carrying a ball in your box today, I hope this essay offers you some clarity, peace, and validation.

Read the full essay below.

Why Time Doesn’t Heal All Wounds – But It Does Make Them Bearable

“Grief never ends… but it changes. It’s a passage, not a place to stay. Grief is not a sign of weakness, nor a lack of faith. It is the price of love.”

I spend most of my professional life engrossed in the transformative promise of artificial intelligence in cancer care.

I write about the digital twins that might soon predict how a tumor will respond to a specific treatment. I discuss AI systems that will catch minute changes earlier, match patients to complex clinical trials faster, and, critically, reduce the crushing administrative burden that steals hours from patient care every single day.

My core belief – the theme driving my work in “Driving Smarter Cancer Care”- is that this technology will give us back something we’ve dangerously eroded in modern oncology: time. Time to sit quietly with a patient. Time to truly listen to their fears. Time to build the kind of human relationships that make this work meaningful, not just exhausting.

But here is a truth I hold with equal certainty: Even with all the AI in the world, even with perfect predictive models, personalized treatments, and algorithmic efficiency, we will not save everyone.

Cancer will still take people we love. Treatments will still fail. Families will still sit in our offices, hearing words they never wanted to hear.

And in those moments – in the depths of those dark, unavoidable caves where grief lives – no chatbot can follow. No algorithm can comfort. No technology can do the essential, challenging work that humans must do for each other.

This essay is about that work. It’s about grief – how we carry it and how we help both our patients and ourselves survive it.

The Question That Haunts Us

One of the most challenging moments in an oncologist’s career is when a patient or family member looks up at you and asks, “Will this pain ever go away?”

For years, I wrestled with how to answer that question honestly without eliminating hope. I felt obligated to tell them the truth – that the emptiness doesn’t disappear – but I also needed them to grasp that healing is absolutely real, even when it doesn’t look like the total erasure of pain our culture expects.

Then a colleague shared an analogy with me that changed everything – not just my conversations with patients, but me personally. Because we, the physicians, the nurses, the social workers – we carry losses, too. We sit with people in their final days. We deliver devastating news. We remember our patients years after they’re gone, holding a small piece of their story in our own personal archive.

This analogy, known as the ball-in-the-box, has been the most powerful tool I have found for understanding my own grief and helping countless patients understand theirs.

The Box We All Carry

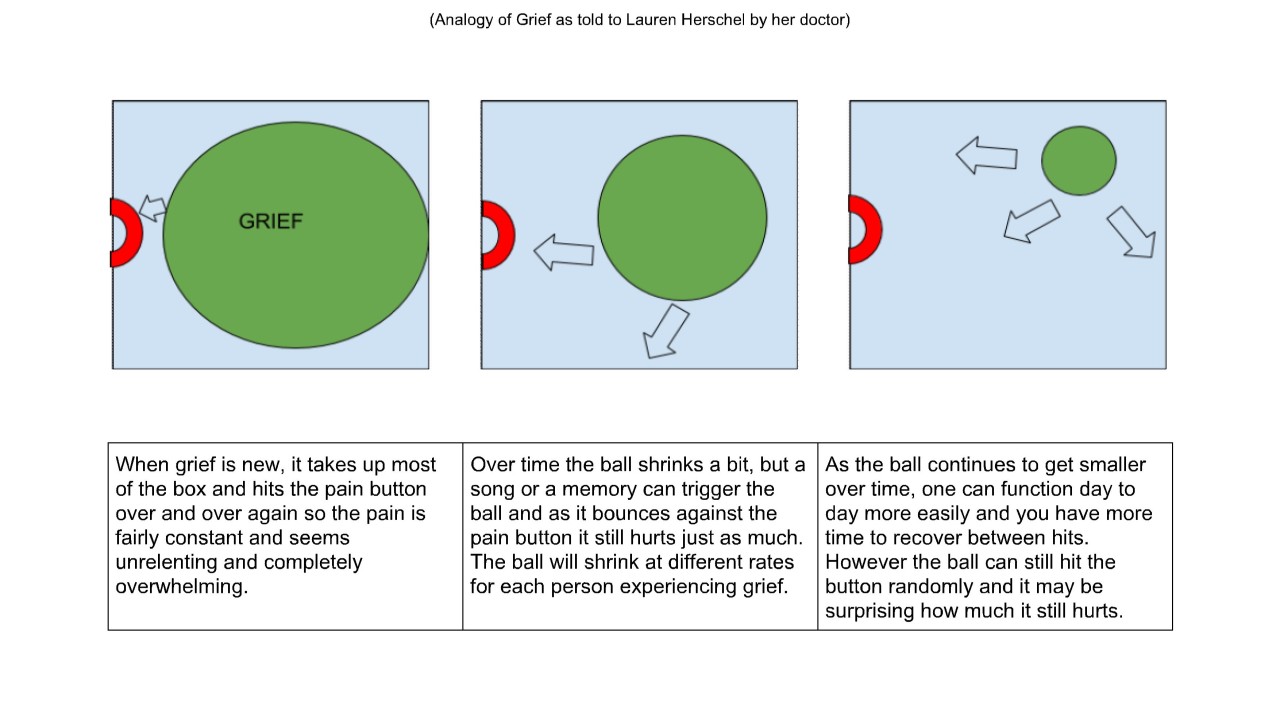

Imagine your grief as a ball inside a box. On one side of that box, there is a pain button.

That’s the whole concept. It’s simple, intensely visual, and devastatingly accurate in its mechanism.

In the beginning – those first days, weeks, maybe months after a profound loss—that ball is enormous. It fills the entire box. It’s so big that you can’t move, can’t breathe, can’t think without it constantly pressing that pain button. The ball rattles around, hitting the button over and over and over.

It is uncontrollable. It is inescapable. It just keeps hurting.

This is the visceral reality of early grief. It is relentless and all-consuming.

You wake up, and the pain is present. You try to work, to parent, to function—and the pain is there. Because the ball is so large, the slightest movement, the most basic thought, makes it slam into the button.

During this stage, well-meaning friends will tell you things like, “Time heals all wounds,” or, “You’ll get over this,” or, “They’d want you to be happy.” And these phrases, however kindly intended, feel like bitter lies. How could it ever get better when, right now, the ball is enormous, the button is constantly pressed, and the pain is a physical force?

But here is the truth I’ve seen proven, time and time again: It does change.

The Ball Gets Smaller

This is the part that offers genuine, grounded hope, both as a physician and as a human being who has experienced loss.

Over time – and there is no prescribed timeline for this, so please release yourself from that expectation immediately—the ball gets smaller.

Not gone. Not disappeared. Not “healed” in the transactional way our culture uses the word.

Smaller.

As weeks, months, and even years pass, that ball gradually shrinks. It occupies less space in the box. It doesn’t press the pain button as constantly. There is now more room in the box for other things: for laughter that doesn’t feel guilty. For memories that bring genuine smiles instead of only tears. For new experiences that don’t feel like a betrayal of the person you lost.

The ball is still there, still bouncing around. And here is the absolutely crucial part that the analogy captures so perfectly: When it hits that pain button, it hurts just as intensely as it did in the very beginning.

This is what confuses and often frightens people. They believe healing means the pain itself should diminish in intensity. But that’s not how it works. The grief, when it strikes, can feel just as raw, just as shocking years later as it did in those early, immediate days.

The difference is frequency, not intensity.

The Unscheduled Hit

You can be driving to work, thinking about a complex case or an upcoming meeting, when a particular song comes on the radio. Without warning, the ball slams into the button. Suddenly, you’re pulled over, crying with a force that shocks you.

You might be at your child’s college graduation, filled with pure joy and pride, and you think about how the person you lost should be here to witness this moment. The ball hits the button. Grief crashes over you in the middle of a celebration.

You’ll be truly fine—genuinely fine—for weeks or even months. Then, on some random Tuesday, for no reason you can identify, the ball seems to grow huge again. It’s hammering that button relentlessly, just as it did in the early days.

This is not a failure of grieving. This doesn’t mean you’re broken or that you’ve regressed to the beginning.

It means you loved someone. And that love doesn’t expire. It doesn’t follow a social schedule. It doesn’t care about our expectation of how long sadness should last.

I tell my patients (and remind myself): some days the ball is big. Some days it’s small. You cannot control which kind of day you will have. All you can do is permit yourself to feel whatever you’re feeling—and trust that the big, overwhelming days will pass, just as they did before.

What Healing Actually Looks Like

Here is the essential lesson I’ve absorbed about grief after two decades in oncology: Healing isn’t about the ball disappearing. It is about learning to live with the ball occupying less space.

You rebuild your life around the loss. You don’t “get over it” or “move on”—phrases that wrongly suggest leaving the person behind. Instead, you learn to carry them differently.

The box containing your grief ball begins to fill with other elements. New relationships. New experiences. New versions of yourself. These new things don’t replace the person you lost—nothing ever could. But they protect that pain button. They create cushioning. They give the ball less room to rattle around and dictate your life.

And slowly, painstakingly, beautifully—you become whole again.

Not the same. Never the same person you were before. But whole.

You laugh without the immediate, accompanying guilt. You make plans for the future. You can speak about the person you lost without falling apart every time you do. You find meaning in the path ahead—not because the loss was a grand cosmic plan (I reject those platitudes), but because you have chosen to honor their memory by continuing to live fully.

The Irreplaceable Human Work

I want to pivot for a moment and speak directly to my fellow physicians, nurses, healthcare leaders, and anyone excited about what AI promises our field.

We are right to be excited. AI will read scans faster. It will identify patterns we miss. It will handle the crushing weight of prior authorizations and documentation—the administrative chaos that keeps us from doing what we’re trained to do.

But AI will never do this part. It will never sit in the grief with our patients. It will never carry the weight of the collective losses that accumulate over decades of practice.

We carry balls in our boxes, too.

I remember a 27-year-old Hodgkin’s patient I lost fifteen years ago. I remember the burly construction worker sobbing on his wife’s belly as he said goodbye at her bedside. I remember the 26-year-old college volleyball coach whose cancer returned months after we celebrated her remission. I remember those three brutal days with Hospice in my parents’ bedroom as we said goodbye to my mom when I was just a kid.

They are all in my box. Small balls now, most of them. But sometimes they hit the button—usually when I’m treating a new patient who reminds me of them, or when I’m sitting with a family, delivering news I desperately wish I didn’t have to give.

We are taught to maintain professional distance, but we are rarely taught what to do with the grief that accumulates despite our best efforts. We are not taught that carrying these losses is a fundamental part of the work, a solemn privilege of being present during someone’s most vulnerable moments.

This is the irreplaceable human work of medicine. This is what we will still be doing long after AI has optimized everything else, and we will still be walking into the dark caves with our patients, sitting in the grief, and carrying pieces of their stories with us.

The ball-in-the-box analogy has helped me understand that I don’t need to “get over” these losses. I don’t need to wall myself off from them completely. I need to let the balls get smaller while still honoring what each patient and each experience taught me.

This is how we sustain ourselves in this demanding field without burning out or shutting down emotionally. We acknowledge the grief. We allow it to exist. We trust it will get smaller. And we keep showing up – for the next patient, the next family, the next person who needs someone to walk into the cave with them.

If AI gives us back even a few more hours per week to do this profoundly human work, it will have been worth every algorithm we’ve trained.

Living With the Ball

So, what action do we take with this awareness? How do you live a whole life with a ball bouncing around in your box?

First, stop judging yourself for having bad days. Is the ball giant today? Okay. That is allowed. That is normal. That is grief doing what grief does. You don’t have to be “strong.” You don’t have to be “over it.” You just have to get through today.

Second, give it language. Tell a trusted person, “The ball is huge today,” or “The ball hit the button hard this morning.”

Giving your grief language allows others to understand your experience without having to explain the entire complicated mess of emotions that accompanies loss.

Third, honor the person you lost by living. Not by forgetting them. Not by moving on from them. But by actively filling your box with experiences and relationships and moments that they would have been proud of. The ball gets smaller not because you love them less, but because you are deliberately creating space for the things they would have wanted for you.

Fourth, trust the process. There will be setbacks. There will be days when the ball seems inexplicably huge again. There will be unexpected triggers that knock you sideways. This is all part of healing. The trajectory isn’t a straight line, but the progress is real.

A Message of Hope

If you are reading this in the midst of overwhelming grief—if your ball is enormous, the pain button is constantly pressed, and you cannot imagine it ever getting better—I want you to hold onto this truth:

The ball will get smaller.

Maybe not today. Perhaps not for weeks or months. But it will.

You will laugh again without feeling guilty. You will make plans for the future again. You will have entire days where the ball doesn’t hit the button at all. And when it does hit—because it will—you will be stronger than you think. You will survive it, just as you have every time it’s hit since the loss.

The person you lost wouldn’t want you to stop living. They wouldn’t want the ball to stay huge forever. They would want you to heal – not forget, not replace them, but heal.

Grief is the price of love. And the fact that your ball is so big right now? That is a profound testament to how deeply you loved. What an incredible gift, even though it hurts so terribly right now.

The ball will get smaller. You will rebuild. You will be whole again, even though you will never be the same.

And that’s not just okay – that’s precisely how it’s supposed to be.”

More posts featuring Douglas Flora.