Christian Hyde, Clinical Assistant Professor at Wayne State University School of Medicine and Chief Executive Officer of Afton Oncology, shared a post on LinkedIn:

“FLASH radiation is in the oncology news a lot. Is it justifiable hope or just hype? Continuing my series, The ABCs of PRT (PRoton Therapy), we’re on F for FLASH.

FLASH entails giving a very high dose of radiation in much less than a second, thus reducing side effects to normal tissue and yet with no worse tumor control in animals. This may sound too good to be true. FLASH does have known downsides like the loss of tight beam shaping from many angles, resulting in hotspots in normal tissue outside the tumor, kind of the opposite of what we’re usually doing with proton therapy or highly conformal X-ray arcs.

As a result of these limitations, I used to think it would just be a ‘Flash in the pan’ so to speak, another passing fad. We’ve been here before, as FLASH was previously studied in the 1960s but there weren’t major X-ray machines capable of doing it in clinic. At the same time, longer treatments with small daily doses had gained popularity as a way of reducing side effects, a trend that peaked in the early 2000s when a course of radiation for prostate cancer reached 9 weeks – 45 daily doses – and has fortunately come down since then.

Oddly enough, what really got my attention in FLASH is what happens if we DON’T achieve dose rates that are fast enough to spare normal cells. It isn’t simply that we don’t do better, but we might actually do worse than going slow. This paradoxical ‘sub-FLASH effect,’ as I call it, has been replicated by 3 top US proton groups at Harvard/MGH, MD Anderson, and New York Proton Center (NYPC).

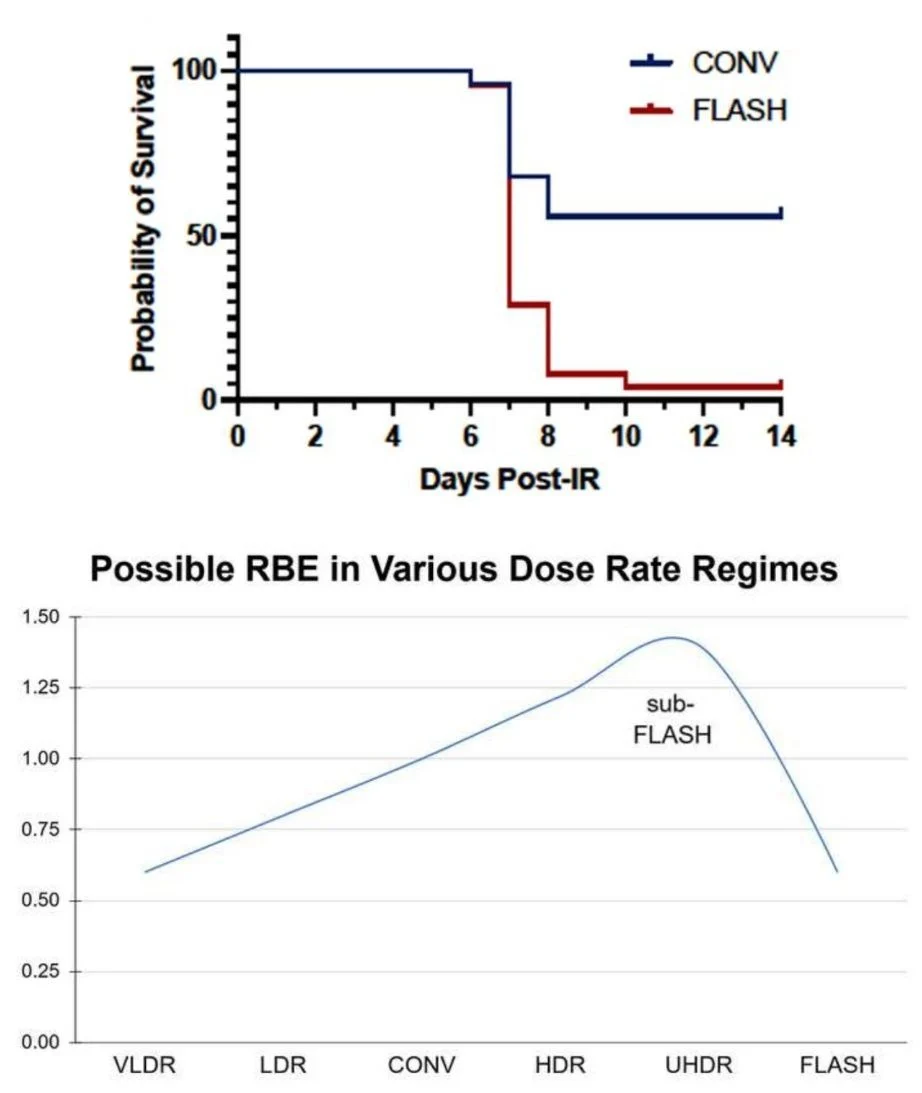

The NYPC article by Brett Bell, et al., showed a 90% death rate among FLASH treated mice compared to 50% among Conventional dose rate following whole-abdomen proton radiation in a single 14 Gray dose (see graph). This despite a mean dose rate of 80 Gray/second, well above the 40 Gy/s FLASH threshold suggested by others. Clearly, something interesting is going on when results cannot be replicated, and I think it indicates that Instantaneous Dose Rate is more important than Mean Dose Rate.

You can the read the article here.

The usual dose rate effect, in which higher dose rates are less easily repaired and thus have a higher Relative Biological Effectiveness (RBE), may extend into the sub-FLASH domain. What this means to me as a clinician is that we have to be >99% sure that we are going to clear that FLASH hurdle every time, or risk doing more harm than good. Hopefully the next generation of machines will do it, and I plan to devote a good portion of my future to this effort.”