HPV and Cancer: From Risks to Prevention, Diagnosis, and Future Therapies

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection worldwide, affecting nearly all sexually active individuals at some point in their lives. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI), there are over 200 types of HPV, with about 40 types infecting the genital and mucosal areas. These types are broadly categorized into low-risk strains, which typically cause benign conditions like warts, and high-risk strains, which are strongly linked to the development of several cancers. Persistent infection with high-risk HPV types, particularly HPV 16 and 18, is the primary cause of cervical cancer and is also associated with cancers of the anus, penis, vagina, vulva, and oropharynx.

The CDC estimates that HPV causes more than 37,000 cancer cases annually in the United States alone. While most HPV infections clear naturally without causing symptoms or health problems, persistent infections can lead to cellular changes that increase cancer risk over time. Public health agencies emphasize that HPV-related cancers are largely preventable through vaccination and regular screening. The HPV vaccine, recommended for preteens and young adults, can prevent the majority of cancers caused by HPV.

Photo:Depositphotos

This article explores the risks associated with HPV and cancer , the different virus types, and the critical links between HPV infection and cancer, highlighting the importance of awareness, prevention, and early detection. In this article, you will find out about the different types of HPV, how the virus is transmitted, and the mechanisms by which high-risk HPV strains can cause cancer. It also highlights the cancers linked to HPV and explains the critical role of vaccination and regular screening in preventing HPV-related diseases.

HPV Unveiled: Decoding the Virus Behind Common Infections

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is an extremely common virus that infects the skin and mucous membranes, especially in the genital and oral areas. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), nearly everyone who is sexually active will get HPV at some point in their lives. In the United States alone, about 42.5 million people were estimated to be infected with at least one HPV type that can cause disease in 2018. Among adults aged 18 to 59, approximately 40% had a genital HPV infection, with 42% of men and 38% of women affected during 2013–2014. Most HPV infections cause no symptoms and clear naturally within 1–2 years, but some types can cause warts or lead to cancer.

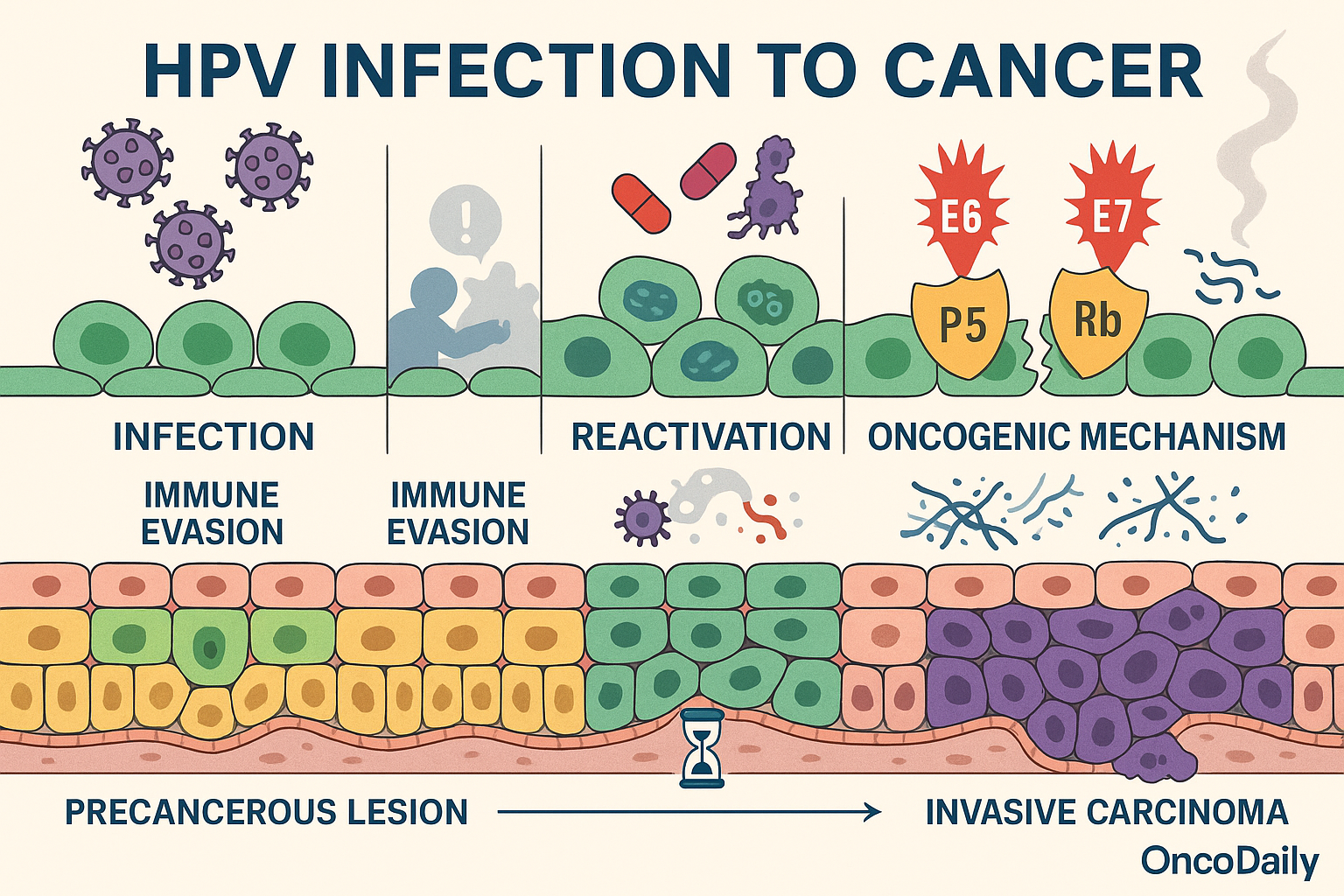

HPV infects the basal cells of the epithelium through tiny cuts or abrasions. Once inside, the virus slowly replicates by hijacking the host’s cells, producing proteins that help it survive without immediately killing the infected cells.

High-Risk HPV Types: The Viral Strains Driving Cancer

HPV types are divided into low-risk and high-risk groups. Low-risk types, such as HPV 6 and 11, cause genital warts but rarely lead to cancer. High-risk types, especially HPV 16 and 18, are responsible for most HPV-related cancers. These high-risk types produce proteins called E6 and E7 that interfere with the cell’s normal protective mechanisms. E6 disables p53, a protein that repairs damaged DNA or triggers cell death if damage is severe, while E7 inactivates pRb, which controls cell division. This disruption allows infected cells to grow uncontrollably, increasing cancer risk.

From Infection to Cancer: The HPV Oncogenic Journey

Most HPV infections are cleared naturally by the immune system. However, when high-risk HPV types persist, the viral DNA can integrate into the host’s genome, leading to increased production of viral proteins E6 and E7. These proteins disrupt the cell’s normal tumor-suppressing mechanisms, causing genetic instability that, over many years, can result in precancerous lesions and eventually invasive cancer. Lifestyle factors such as smoking and conditions that weaken the immune system further elevate this risk.

Interestingly, some HPV strains can remain dormant within the body after the initial infection, existing in a latent state without causing active disease. Scientific studies, including those summarized in Clinics and research available via the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), explain that HPV evades immune detection by altering immune signaling pathways and reducing the effectiveness of the body’s antiviral responses. The viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 play key roles in this immune evasion.

Certain triggers such as immunosuppression or co-infections can reactivate these latent HPV infections. Research published in the Journal of Virology demonstrates that when the immune system is compromised, dormant HPV genomes can become active again, leading to renewed viral replication and an increased chance of persistent infection. This reactivation contributes to the long-term risk of developing HPV-associated cancers.

Beyond Cervical Cancer: The Spectrum of HPV-Associated Malignancies

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is responsible for a wide range of cancers, with cervical cancer being the most prominent and well-studied. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), nearly all cases of cervical cancer, about 91%, are caused by persistent infection with high-risk HPV types, primarily HPV 16 and 18. Cervical cancer develops when persistent HPV infection leads to precancerous changes in the cervical cells, which, if untreated, can progress to invasive cancer over several years. Routine screening through Pap smears and HPV testing has significantly reduced cervical cancer incidence and mortality by detecting and allowing treatment of precancerous lesions early.

Despite this, cervical cancer remains a major public health concern worldwide, especially in populations with limited access to screening and vaccination (CDC, 2023; WHO, 2023).

Beyond cervical cancer, HPV causes several other malignancies, each with distinct epidemiological and clinical features:

Anal Cancer: Over 90% of anal cancers are linked to high-risk HPV infection, predominantly HPV 16. The incidence of anal cancer has been increasing, particularly among immunocompromised individuals such as those with HIV. In the United States, approximately 7,854 new anal cancer cases occur annually, with about 91% attributable to HPV (CDC, 2023).

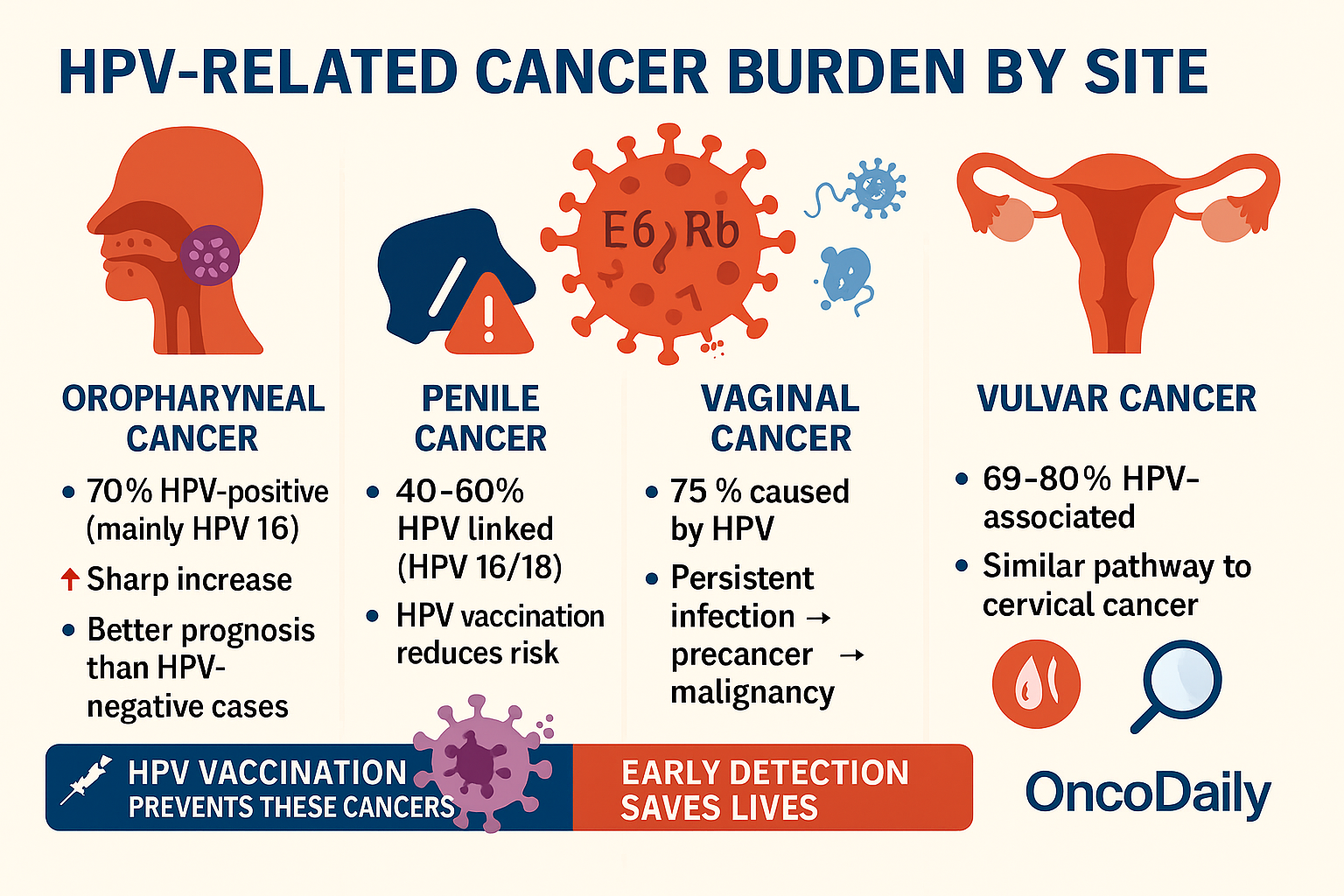

- Oropharyngeal Cancer: About 70% of oropharyngeal cancers. Like cancers of the middle throat behind the mouth are HPV-positive, mainly caused by HPV 16. These cancers have risen sharply in recent decades, especially among men, and now represent a significant portion of head and neck cancers. The prognosis for HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer is generally better than for HPV-negative cases (CDC, 2023; NCRI, 2025).

- Penile Cancer: Roughly 40–60% of penile cancers are associated with high-risk HPV infection, particularly HPV 16 and 18. Penile cancer is relatively rare but carries a significant burden in regions with lower rates of circumcision and HPV vaccination (CDC, 2023).

- Vaginal and Vulvar Cancers: HPV causes about 75% of vaginal cancers and around 69–80% of vulvar cancers. These cancers share similar pathogenic mechanisms with cervical cancer, involving persistent infection with high-risk HPV types that induce precancerous changes and eventual malignancy (CDC, 2023; WHO, 2023).

Together, these HPV-associated cancers constitute a substantial health burden. The CDC estimates that approximately 37,800 HPV-attributable cancers are diagnosed annually in the United States (2017–2021 data), with cervical cancer accounting for about 10,800 cases, or 29% of these (CDC, 2023). The remaining cases include anal, oropharyngeal, penile, vaginal, and vulvar cancers, underscoring HPV’s broad oncogenic impact beyond the cervix.

Globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that HPV causes around 690,000 new cancer cases annually, with cervical cancer comprising the majority of these. In countries with limited screening and vaccination, cervical cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer death among women (WHO, 2023).

You Can Also Read Cervical Cancer Screening: Who Needs a Pap Smear or HPV Test and When? by Oncodaily

Silent Threat: Recognizing HPV Symptoms and Clinical Signs

HPV infections are often silent, especially those caused by high-risk types. Low-risk HPV infections may cause visible genital warts, but high-risk infections rarely produce symptoms until advanced disease develops. Precancerous changes caused by HPV are usually asymptomatic and detectable only through medical tests. Symptoms of HPV-related cancers vary by site and may include abnormal bleeding, lumps, or persistent pain, underscoring the importance of medical evaluation when such signs occur.

Battling HPV: Current Treatments for HPV-Related Conditions

Treatment for HPV-related conditions is tailored to the specific clinical manifestation and the severity of disease:

Genital Warts (Low-Risk HPV Types):

Genital warts, caused mainly by HPV types 6 and 11, are managed with topical agents such as imiquimod, podophyllotoxin, or sinecatechins. These medications stimulate local immune responses or directly destroy wart tissue. Cryotherapy (freezing with liquid nitrogen) and surgical removal are also commonly used, especially for larger or resistant lesions. In some cases, electrosurgery or laser therapy may be considered for extensive or recurrent warts.

Precancerous Lesions (High-Risk HPV Types)

For precancerous changes in the cervix (such as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, CIN), treatments focus on removing or destroying abnormal tissue to prevent progression to cancer. Techniques include loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), cold knife conization, laser ablation, or cryotherapy. Similar approaches are used for precancerous lesions in the anus, vulva, vagina, and penis. The choice of treatment depends on lesion size, location, and patient factors.

Invasive HPV-Associated Cancers

Once cancer develops, treatment becomes more complex and is usually multidisciplinary

- Surgery is often the first-line option for early-stage cancers, aiming to remove the tumor and surrounding tissue.

Radiation therapy may be used alone or in combination with surgery or chemotherapy, especially for locally advanced disease.

Chemotherapy (e.g., cisplatin-based regimens) is used for advanced, recurrent, or metastatic cancers and may be combined with radiation for synergistic effects. - Targeted therapies are being explored, particularly for recurrent or metastatic disease, but are not yet standard for most HPV-associated cancers.

Future of HPV: Advances in Understanding and Therapeutic

Recent scientific advances have significantly deepened our understanding of how HPV contributes to cancer and how these cancers might be better treated in the future. Research shows that when HPV DNA integrates into the host genome, it can create extrachromosomal DNA (ecDNA) structures and induce chromosomal rearrangements. These changes contribute to tumor heterogeneity (the presence of diverse cancer cell populations within a tumor) and are linked to resistance to standard treatments. Genomic and epigenetic profiling of HPV-positive cancers has revealed distinct molecular signatures, opening the door to personalized medicine approaches.

Immunotherapy and Therapeutic Vaccines:

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors, drugs such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab (which target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway) have shown promise in treating recurrent or metastatic cervical and head-and-neck cancers, particularly those that are HPV-positive. These therapies work by unleashing the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells expressing HPV antigens.

- Therapeutic Vaccines: Unlike preventive HPV vaccines, therapeutic vaccines are designed to stimulate the immune system to target and destroy cells already infected with HPV or transformed by HPV. Several therapeutic vaccines targeting E6 and E7 oncoproteins are in clinical trials, showing encouraging results in inducing immune responses and, in some cases, regressing precancerous lesions or tumors.

- Adoptive T-cell Therapy: This approach involves engineering a patient’s own T-cells to recognize HPV-specific antigens, then infusing them back to attack HPV-infected or cancerous cells. Early-phase trials are ongoing.

- Combination Therapies and Personalized Medicine:Ongoing research is exploring combinations of immunotherapy, targeted agents, and traditional treatments to overcome resistance and improve outcomes. For example, combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with therapeutic vaccines or with chemotherapy/radiation is under investigation in multiple clinical trials.

- Biomarker Development: Genomic and epigenetic biomarkers are being developed to identify patients most likely to benefit from specific therapies and to monitor response or recurrence. This precision medicine approach aims to tailor treatment to the individual’s tumor profile

Clinical Trials and Future Directions:

Numerous clinical trials are underway to test new drugs, vaccine platforms, and immunotherapy combinations for HPV-associated cancers. These advances offer hope for more effective, less toxic, and more personalized treatments in the coming years.

You Can Also Read Oncoviruses and Their Role in Human Cancer: Types, and Global Impact by Oncodaily

How Close Are We to Defeating HPV?

While complete eradication of HPV remains a challenge, remarkable progress in vaccination, screening, and emerging therapies brings us closer than ever to controlling this virus. With continued innovation and global access to prevention and treatment, the vision of dramatically reducing HPV-related cancers is within reach. The question now is how quickly and equitably we can turn these advances into real-world impact.

Written by Marine Marashlian

FAQ

What is HPV and how is it transmitted?

HPV (human papillomavirus) is a very common sexually transmitted infection that usually causes no symptoms and often clears on its own but can sometimes lead to genital warts or cancers such as cervical, anal, and throat cancer. It spreads primarily through direct skin-to-skin contact during sexual activities, including vaginal, anal, and oral sex, as well as through genital-to-genital, oral-genital, and hand-genital contact. HPV can also be transmitted from a pregnant person to their baby during childbirth. Condoms reduce but do not completely eliminate the risk because HPV can infect areas not covered by condoms.

What are the symptoms of HPV infection?

Most HPV infections cause no symptoms and go unnoticed. When symptoms do appear, they may include:Genital warts (small, raised, or cauliflower-shaped growths on the genitals, anus, mouth, or throat) Itching, discomfort, or pain in the affected area, Rarely, abnormal bleeding or lesions High-risk HPV types can cause cell changes that may lead to cancers (cervical, anal, throat, etc.), but these usually have no symptoms until advanced stages. Regular screenings are important for early detection.

How common is HPV?

HPV is extremely common, with about 85-90% of sexually active people expected to get an HPV infection at some point in their lives. In the U.S., around 13 million people, including teens, get infected each year. Globally, nearly 1 in 3 men have at least one genital HPV strain, and many women have high rates of cervical HPV, especially in certain regions like Sub-Saharan Africa.

What are the differences between low-risk and high-risk HPV types?

Low-risk HPV types, mainly HPV 6 and 11, cause genital warts—small, raised or flat growths on the genitals or anus. These warts are usually harmless and treatable with topical medicines or minor procedures. They rarely lead to cancer. High-risk HPV types, like HPV 16 and 18, don’t cause warts but can cause persistent infections that lead to abnormal cell changes, especially in the cervix. These changes may progress to cancers such as cervical, anal, or throat cancer if untreated. High-risk HPV infections often have no symptoms and are detected through screening tests. Early treatment of abnormal cells can prevent cancer development.

Which cancers are caused by HPV?

HPV causes several cancers, primarily: Cervical cancer (most common HPV-related cancer) , Anal cancer, Vulvar cancer, Vaginal cancer, Penile cancer, Oropharyngeal (mouth and throat) cancer. High-risk HPV types, especially HPV 16 and 18, are responsible for most of these cancers.

Can HPV infections go away on their own?

About 80% to 90% of HPV infections clear spontaneously within two years, with many resolving within 6 to 12 months. Around 70% clear within one year and 91% within two years. The immune system typically controls and eliminates the virus, preventing progression. However, some high-risk infections can persist and may lead to precancerous changes or cancer if not monitored. There is no cure for HPV itself, but the infection often goes away on its own without treatment. How can HPV-related cancers be prevented? HPV-related cancers can be prevented by HPV vaccination, regular cervical screening (Pap and HPV tests), practicing safe sex (using condoms), and avoiding smoking. These measures reduce infection risk and detect early changes before cancer develops.

Who should get the HPV vaccine and when?

The HPV vaccine is recommended for all boys and girls starting at age 11 or 12, but can be given as early as age 9. It’s also advised for everyone up to age 26 if not vaccinated earlier. Adults aged 27 to 45 may get the vaccine after discussing with their doctor, though it’s less effective at older ages.

Can you get HPV more than once or after vaccination?

Yes, you can get HPV more than once because infection with one HPV type does not protect against others, and even the same type can recur after clearing. HPV vaccination greatly reduces the risk of infection with the covered HPV types but does not guarantee complete protection against all types or reinfection. Recurrence of HPV infections, including vaccine-covered types, is relatively common, especially with new sexual partners or high-risk behavior. Vaccination provides strong immune protection and lowers the chance of new infections and recurrences but does not cure existing infections.

How can HPV-related cancers be prevented?

HPV-related cancers can be prevented by HPV vaccination, regular cervical screening (Pap and HPV tests), practicing safe sex (using condoms), and avoiding smoking. These measures reduce infection risk and detect early changes before cancer develops.

-

Challenging the Status Quo in Colorectal Cancer 2024

December 6-8, 2024

-

ESMO 2024 Congress

September 13-17, 2024

-

ASCO Annual Meeting

May 30 - June 4, 2024

-

Yvonne Award 2024

May 31, 2024

-

OncoThon 2024, Online

Feb. 15, 2024

-

Global Summit on War & Cancer 2023, Online

Dec. 14-16, 2023