Craniopharyngioma: Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatment, and 2025 Breakthroughs in Targeted Therapy and Precision Care

Craniopharyngioma is a rare, histologically benign yet clinically challenging brain tumor that most commonly arises in the sellar and suprasellar region near the pituitary gland and hypothalamus. Affecting both children and adults, this tumor’s proximity to critical neuroendocrine and visual structures often results in significant morbidity, even when successfully treated. With a complex blend of surgical, hormonal, and oncologic considerations, the management of craniopharyngioma has evolved dramatically in recent years. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the tumor’s classification, causes, symptoms, diagnostic approach, and treatment strategies, while highlighting the most significant advances in care as of 2025, including precision-targeted therapies and functional outcome preservation.

Read More About Brain Cancer on Oncodaily

What Is Craniopharyngioma?

Craniopharyngioma is a rare, typically benign (non-cancerous) brain tumor that arises near the pituitary gland and hypothalamus, in a region called the sellar/suprasellar space. It originates from remnants of Rathke’s pouch, an embryonic precursor of the anterior pituitary. Although histologically benign, craniopharyngiomas are considered clinically aggressive due to their proximity to critical brain structures and tendency to recur (Muller et al., 2019).

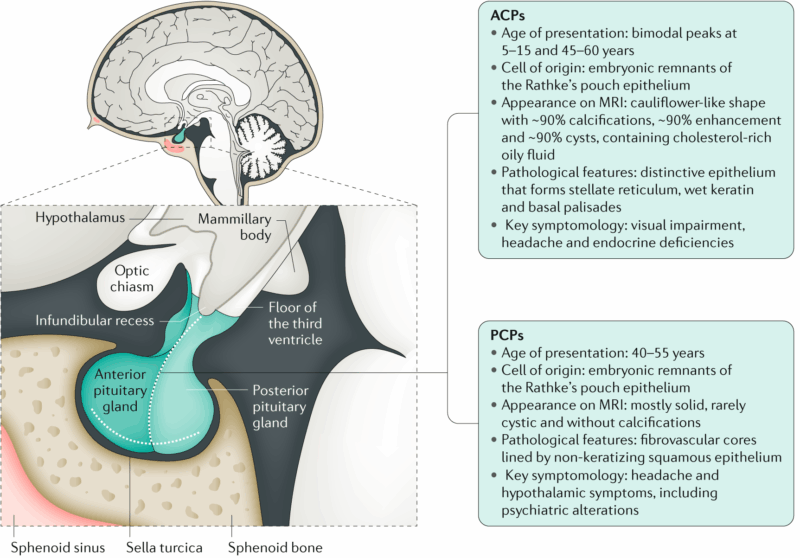

These tumors occur in both children and adults, with a bimodal age distribution—most commonly diagnosed in children aged 5–14 years and in adults between 40–60 years. Despite their benign nature (WHO Grade I), they can cause significant morbidity due to compression of nearby structures such as the optic chiasm, hypothalamus, and pituitary gland.

Classification of Craniopharyngioma

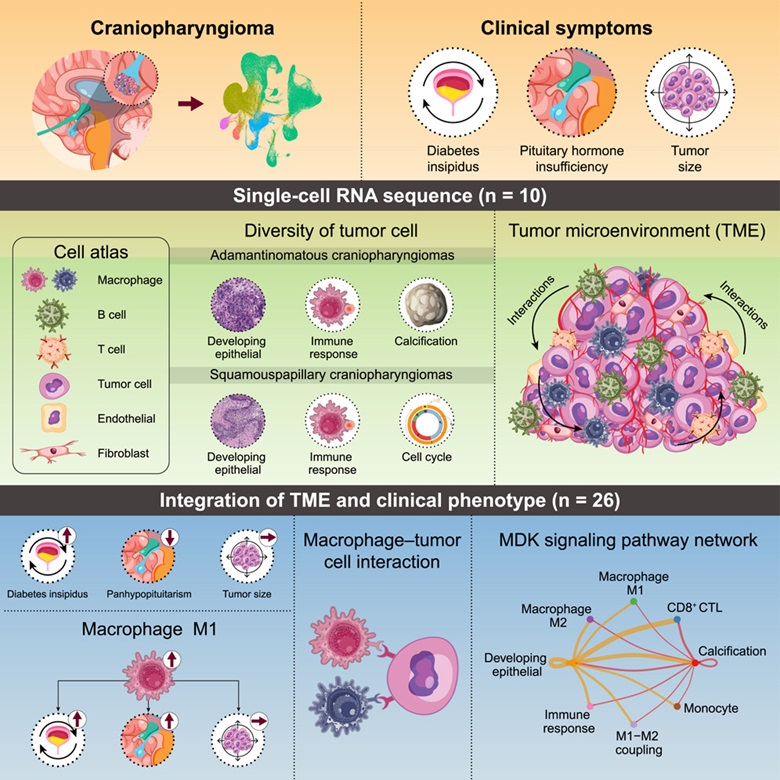

Craniopharyngiomas are classified into two main types: adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma (ACP) and papillary craniopharyngioma (PCP), as defined by the 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of CNS tumors. Adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas are more common in children and are histologically characterized by calcifications, “wet” keratin, and palisading epithelium. These tumors are typically associated with mutations in the CTNNB1 gene, which encodes beta-catenin, leading to activation of the WNT signaling pathway. In contrast, papillary craniopharyngiomas occur almost exclusively in adults and show well-differentiated squamous epithelium without calcifications or keratin nodules. This subtype is nearly always driven by the BRAF V600E mutation, which activates the MAPK pathway. The distinction between the two is critical, as it informs both prognosis and therapeutic strategy, with targeted therapies such as BRAF inhibitors showing promise in papillary craniopharyngiomas (Brastianos et al., 2014; WHO CNS 5, 2021).

Causes of Craniopharyngioma

The exact cause of craniopharyngioma remains unclear, but it is believed to arise from embryonic remnants of Rathke’s pouch, an early developmental structure that contributes to the formation of the anterior pituitary. These tumors are not typically hereditary and are considered sporadic in nature.

In adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma, which is more common in children, the primary molecular driver is a somatic mutation in the CTNNB1 gene, leading to aberrant activation of the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway. This mutation promotes abnormal cell proliferation and is thought to be central to tumor formation (Müller et al., 2019).

Papillary craniopharyngioma, found mostly in adults, is almost always associated with the BRAF V600E mutation, which activates the MAPK signaling pathway, leading to uncontrolled cell growth. This mutation is not inherited but acquired during a person’s lifetime (Brastianos et al., 2014).

There is no known association between craniopharyngioma and environmental exposures, lifestyle factors, or familial cancer syndromes. As of 2025, no preventive strategies exist, and the tumor is generally detected once symptoms emerge due to mass effect or hormonal dysfunction.

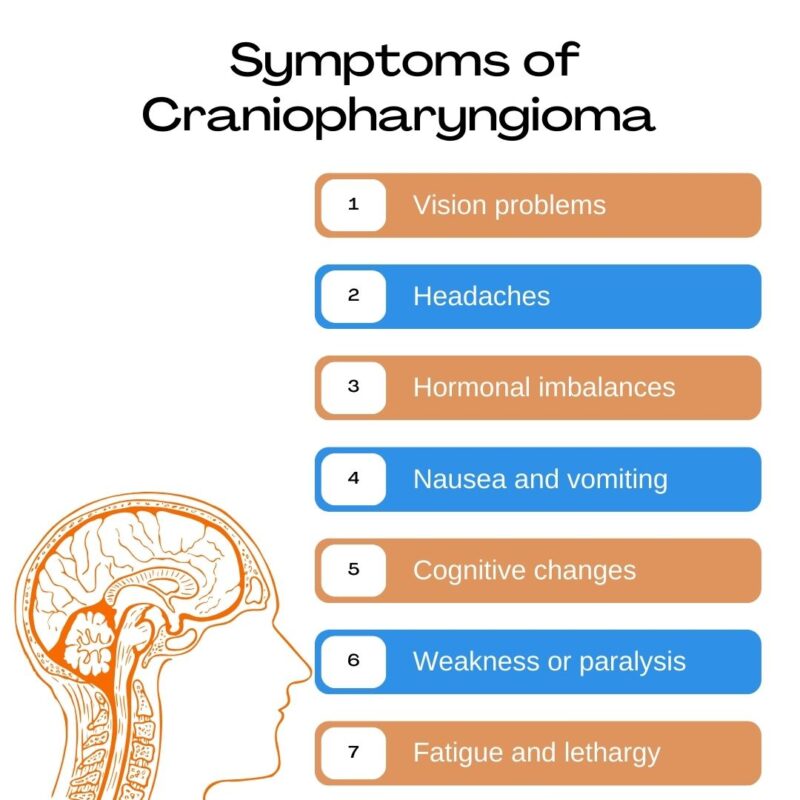

Symptoms of Craniopharyngioma

Craniopharyngioma symptoms arise primarily from the tumor’s location near the pituitary gland, hypothalamus, and optic chiasm. As the tumor grows, it exerts pressure on these critical structures, leading to a range of neurological, visual, and endocrine disturbances.

Patients often present with progressive headaches, especially due to increased intracranial pressure from obstructed cerebrospinal fluid flow. Visual disturbances, such as blurred vision or loss of peripheral vision, are common because of compression of the optic chiasm. Hormonal dysfunction is frequent, as the tumor can disrupt pituitary function, resulting in deficiencies in growth hormone, thyroid hormone, cortisol, or gonadotropins. Children may experience growth failure, delayed puberty, or weight gain. Diabetes insipidus, characterized by excessive thirst and urination, can occur when the posterior pituitary or hypothalamus is affected.

In cases involving the hypothalamus, patients may also experience behavioral changes, memory impairment, sleep disturbances, or hypothalamic obesity, which is particularly challenging to manage. Symptoms usually develop gradually but may worsen suddenly if there is cyst expansion or hemorrhage within the tumor (Müller et al., 2019; Gump et al., 2011).

Diagnosis of Craniopharyngioma

The diagnosis of craniopharyngioma involves a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging studies, hormonal assessments, and histopathological confirmation. Because these tumors are located near the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, patients typically present with signs of hormonal dysfunction, visual disturbances, or increased intracranial pressure, which prompt further investigation.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for detecting craniopharyngiomas. It typically reveals a mass in the sellar or suprasellar region with both solid and cystic components, often with calcifications. The cysts frequently appear hyperintense on T1-weighted imaging due to cholesterol-rich content. Computed Tomography (CT) is useful for identifying calcifications, which are more common in the adamantinomatous subtype.

Endocrine evaluation is essential to assess pituitary function, including measurement of cortisol, thyroid hormones, growth hormone, gonadotropins, and prolactin. Diabetes insipidus may also be diagnosed based on serum sodium, osmolality, and urine concentration tests. Ophthalmological examination, including visual field testing, helps evaluate optic nerve or chiasmal compression. Visual deficits are common at diagnosis and may be irreversible if treatment is delayed.

Definitive diagnosis requires histopathological analysis obtained through surgical resection or biopsy. Adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas exhibit wet keratin, palisading epithelium, and calcifications, and often harbor CTNNB1 mutations. Papillary craniopharyngiomas lack calcifications and typically carry the BRAF V600E mutation, identifiable through immunohistochemistry or molecular testing (Louis et al., 2021; Brastianos et al., 2014).

This integrated diagnostic approach not only confirms the diagnosis but also guides therapeutic decision-making, especially as targeted therapies become more relevant in 2025.

Treatment of Craniopharyngioma

The treatment of craniopharyngioma is multidisciplinary, aiming to achieve maximal tumor control while minimizing damage to critical surrounding structures such as the optic chiasm, pituitary gland, and hypothalamus. The primary treatment modalities include surgery, radiotherapy, hormone replacement, and in select cases, targeted therapy.

Surgical resection is often the first step, especially in symptomatic patients. The goal is maximal safe resection, but complete removal is not always feasible due to the tumor’s proximity to vital neurovascular structures. In pediatric cases, aggressive resection may lead to significant long-term endocrine and cognitive morbidity, so subtotal resection followed by adjuvant radiotherapy is often preferred (Müller et al., 2019).

Radiotherapy, particularly proton beam therapy or fractionated conformal radiotherapy, is commonly used after subtotal resection or for recurrence. It helps control residual tumor growth while sparing surrounding brain tissue. Proton therapy has become increasingly favored in children to reduce long-term radiation-induced toxicity (Merchant et al., 2014).

Read More About Radiotherapy for Brain Tumors on Oncodaily

Hormone replacement therapy is essential for nearly all patients due to damage to the pituitary-hypothalamic axis, either from the tumor itself or treatment. Patients often require lifelong replacement of adrenal, thyroid, gonadal, and growth hormones, as well as management of diabetes insipidus.

Targeted therapy has emerged as a major advance, particularly in papillary craniopharyngioma. These tumors often harbor a BRAF V600E mutation, which can be treated with BRAF inhibitors (e.g., vemurafenib or dabrafenib) alone or in combination with MEK inhibitors (e.g., trametinib). Clinical studies have shown significant tumor shrinkage and symptomatic relief in patients with unresectable or recurrent disease (Brastianos et al., 2014). Cyst-directed therapies, such as intracystic instillation of interferon-α or bleomycin, may be considered in recurrent cases with large cystic components.

In summary, treatment must be highly individualized, taking into account the tumor subtype, patient age, tumor location, and potential for morbidity. The 2025 approach emphasizes tumor control balanced with quality of life, using less invasive options and molecularly guided therapy where appropriate.

Prognosis of Craniopharyngioma

Craniopharyngioma is considered a histologically benign tumor (WHO Grade I), but its prognosis is mixed, due primarily to the tumor’s location near critical brain structures, high recurrence rates, and the long-term impact of treatment-related complications.

Overall survival rates are relatively high. In children, the 5-year survival rate exceeds 85%, and in adults, it ranges between 80% and 90% with modern multidisciplinary care (Müller et al., 2019). However, progression-free survival is lower, especially in cases of subtotal resection without radiotherapy. Recurrence can occur years after initial treatment, necessitating long-term follow-up with MRI and clinical assessment.

The quality of life for survivors is often significantly affected by hypothalamic damage, vision loss, and endocrine dysfunction, including panhypopituitarism and diabetes insipidus. Obesity, particularly hypothalamic obesity, is a major concern in pediatric patients and can lead to metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular complications (Puget et al., 2007). Patients with papillary craniopharyngioma (associated with BRAF V600E mutations) may benefit from targeted therapy, which has been shown to reduce tumor size and delay recurrence, offering new hope for improved outcomes with reduced treatment burden (Brastianos et al., 2014).

In summary, while the long-term survival of craniopharyngioma patients is favorable, the functional prognosis often includes chronic endocrine and neurocognitive complications. Prognosis depends not only on tumor control but also on preservation of neurological and hormonal function, making a tailored, conservative approach critical in both pediatric and adult cases.

2025 Advances in Craniopharyngioma Treatment and Management

In 2025, the landscape of craniopharyngioma care continues to shift toward precision medicine, minimally invasive approaches, and long-term quality-of-life preservation. Major advances are emerging in targeted therapy, radiation techniques, and molecular diagnostics, especially for recurrent and inoperable cases.

A significant breakthrough involves the targeted treatment of papillary craniopharyngioma using BRAF/MEK inhibitors. Since nearly all papillary craniopharyngiomas harbor the BRAF V600E mutation, patients with unresectable or recurrent tumors are now benefitting from vemurafenib or dabrafenib combined with trametinib, leading to dramatic tumor shrinkage and reduced need for high-risk surgery or radiation. This approach, validated in expanded case series and early-phase trials, is becoming a first-line option in select adult patients (Brastianos et al., 2024).

In pediatric and adamantinomatous cases, where BRAF targeting is not applicable, new biologic modifiers targeting the WNT/β-catenin pathway are under investigation. These include inhibitors of β-catenin nuclear translocation, aiming to prevent tumor growth at the molecular level. Although not yet standard of care, early-phase clinical trials are active in Europe and the U.S., evaluating their safety and efficacy in children.

Proton therapy has become increasingly adopted as a preferred modality for patients requiring radiotherapy, particularly children, due to its ability to minimize collateral damage to the developing brain. In 2025, newer proton beam delivery systems, including intensity-modulated proton therapy (IMPT), offer improved precision and better protection of visual and cognitive structures compared to conventional X-ray therapy.

Liquid biopsy and ctDNA detection from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are now being used experimentally to monitor recurrence in patients post-surgery and radiation. This non-invasive tool allows earlier intervention before tumors are visible on imaging and is especially useful in surveillance of subtotal resection cases.

Artificial intelligence (AI)-based radiomics tools are also being applied to MRI and CT scans to predict tumor behavior, recurrence risk, and even molecular subtype without biopsy. These advancements enhance treatment planning and minimize the need for repeated surgeries.

Finally, the emphasis in 2025 has shifted toward functional outcome optimization, including structured neurocognitive rehabilitation programs, endocrine management protocols, and obesity prevention initiatives in hypothalamic-injured children—aiming not just for tumor control, but for long-term survivorship with dignity and independence (Müller et al., 2025; Merchant et al., 2025).

You Can Watch More on OncoDaily Youtube TV

Written by Armen Gevorgyan, MD

FAQ

What is craniopharyngioma?

Craniopharyngioma is a rare, usually benign brain tumor that arises near the pituitary gland and hypothalamus, often affecting hormonal and visual function.

Is craniopharyngioma cancerous?

While considered benign (WHO Grade I), craniopharyngiomas can behave aggressively due to their location and high risk of recurrence.

What causes craniopharyngioma?

They arise from embryonic remnants of Rathke’s pouch. Adamantinomatous types are linked to CTNNB1 mutations; papillary types have BRAF V600E mutations.

Who is at risk for developing craniopharyngioma?

It most commonly affects children aged 5–14 and adults between 40–60 years. There is no known inherited or environmental cause.

What are the symptoms of craniopharyngioma?

Symptoms include headaches, vision problems, hormonal deficiencies, fatigue, growth failure, weight gain, and behavioral changes.

How is craniopharyngioma diagnosed?

Diagnosis is made via MRI, endocrine testing, ophthalmologic exams, and confirmed with histopathology and molecular testing.

What is the standard treatment for craniopharyngioma?

Treatment includes surgical resection, radiation therapy (often proton therapy), and lifelong hormone replacement if the pituitary is affected.

Can craniopharyngioma recur after treatment?

Yes, recurrence is common, especially after partial resection. Long-term follow-up with imaging is essential.

Are there targeted therapies for craniopharyngioma?

Yes, BRAF/MEK inhibitors are effective in papillary craniopharyngioma with BRAF V600E mutations. WNT pathway therapies are under investigation for other types.

What are the long-term effects of treatment?

Many survivors experience hormonal imbalances, cognitive issues, vision loss, or hypothalamic obesity, requiring ongoing multidisciplinary care.

-

Challenging the Status Quo in Colorectal Cancer 2024

December 6-8, 2024

-

ESMO 2024 Congress

September 13-17, 2024

-

ASCO Annual Meeting

May 30 - June 4, 2024

-

Yvonne Award 2024

May 31, 2024

-

OncoThon 2024, Online

Feb. 15, 2024

-

Global Summit on War & Cancer 2023, Online

Dec. 14-16, 2023