Cancer Immunotherapy Revolution: How Engineered Viruses and Pig Sugars Are Unlocking New Cancer Treatments

Cancer Immunotherapy has transformed cancer treatment by helping the body’s own immune system recognize and destroy tumor cells. However, many cancers remain difficult to treat because they can hide from immune detection. A new strategy, developed by immunologist Yongxiang Zhao and supported by immuno-oncologist Brian Lichty at McMaster University, aims to solve this problem in a unique way: by making tumor cells look like pig organs. This approach triggers the immune system to attack the cancer as if it were a foreign invader, using a mechanism similar to how the body rejects pig organ transplants.

In this article, we will explore how this technique works, the science behind it, the early success seen in animal models, its potential advantages, the challenges ahead, and what future clinical trials could mean for cancer treatment.

Background: How the Body Rejects Pig Organs

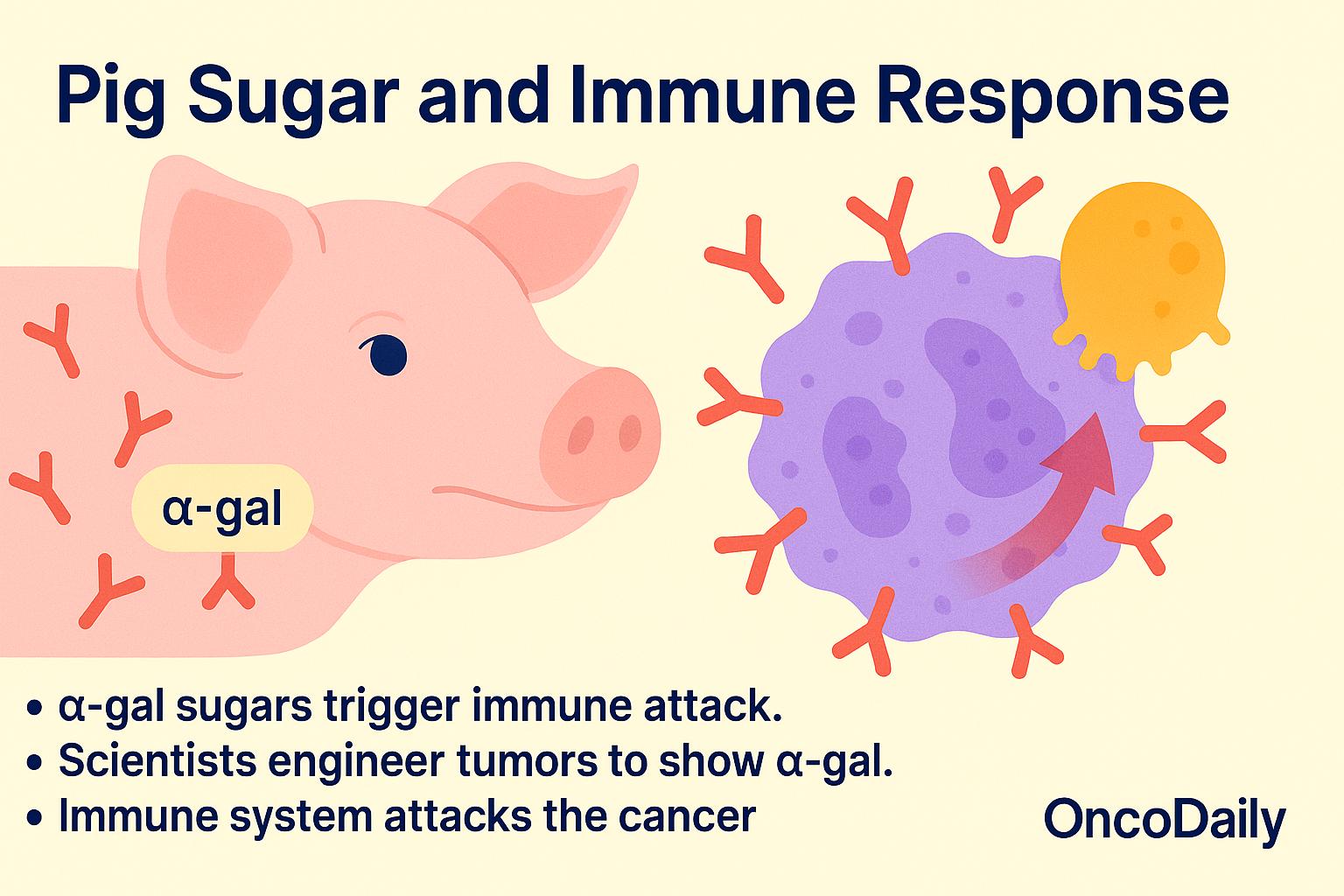

When pig organs are transplanted into humans, the immune system quickly recognizes them as foreign and launches a violent rejection response. This happens mainly because pig cells carry a special sugar molecule on their surface called the α-gal epitope (galactose-α-1,3-galactose).

Humans naturally produce antibodies against α-gal because this sugar is not found in human cells but is common in pigs and other non-human mammals. As a result, when a pig organ enters the human body, these pre-existing antibodies immediately bind to the α-gal sugars, triggering a powerful immune attack that rapidly destroys the foreign tissue. Researchers realized they could use this same mechanism against cancer. By engineering tumor cells to display α-gal-like sugars, they can make cancer cells appear as foreign as a pig organ—forcing the immune system to recognize and attack tumors that would otherwise go unnoticed.

The Mechanism: How the Technique Works

To deliver the pig-specific sugars to cancer cells, the researchers used the Newcastle disease virus, a virus that is harmless to humans but naturally infects birds. Because it does not cause illness in people, it provides a safe platform for genetic modifications. The research team genetically engineered the virus to carry instructions for an enzyme that produces pig-specific sugars like the α-gal epitope. When the engineered virus infects tumor cells, it forces them to start expressing these foreign sugars on their surface—something they would never naturally do.

As a result, the immune system immediately recognizes the coated tumor cells as dangerous invaders, just like it would recognize a transplanted pig organ. This triggers a rapid and powerful immune attack, aiming to eliminate the tumor.

Preclinical Results: Early Animal Testing

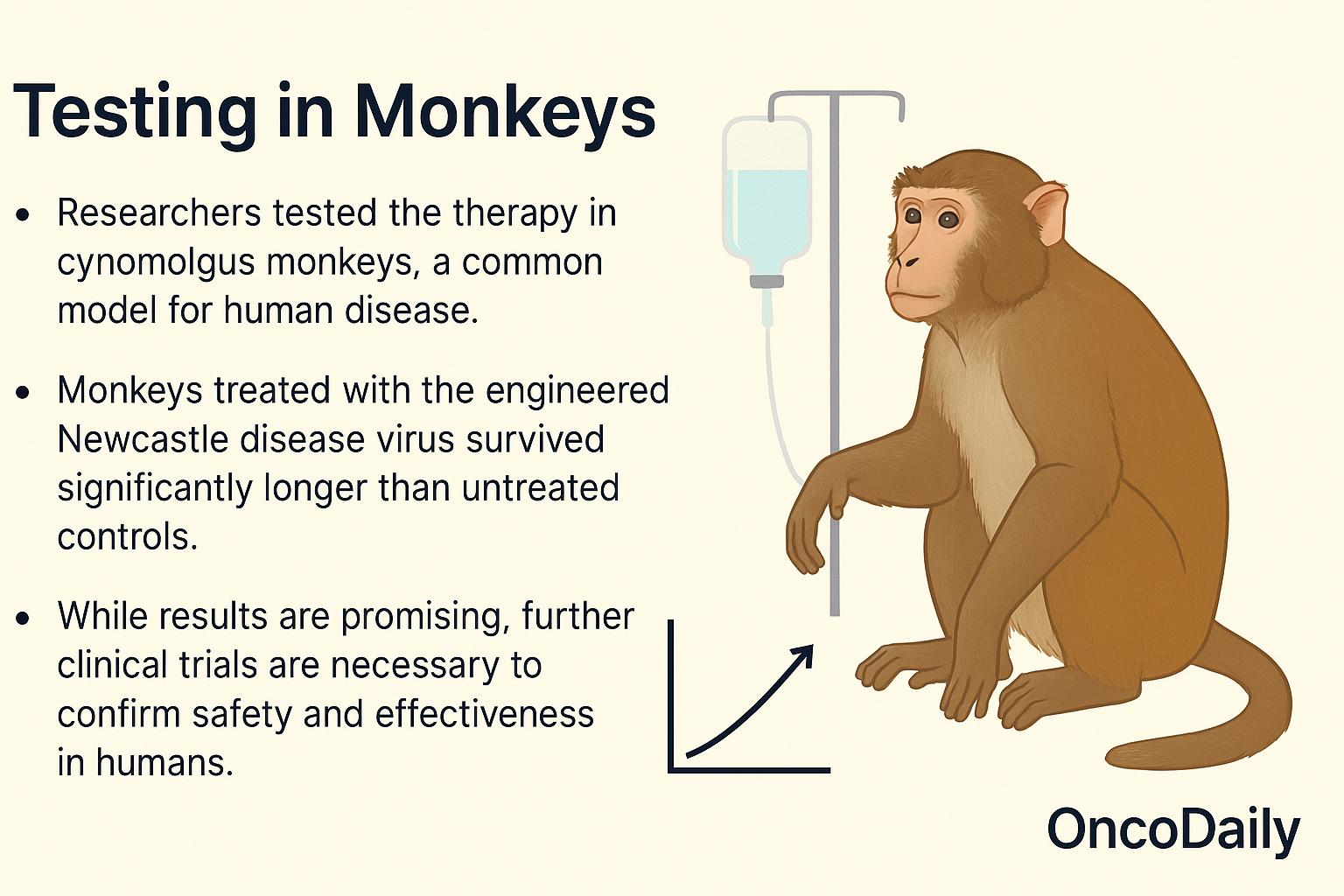

The researchers tested their approach in cynomolgus monkeys, a common animal model for studying human diseases. Monkeys with tumors were divided into two groups: one group received the engineered Newcastle disease virus, and the other received a simple saline solution. The results were promising—monkeys treated with the virus survived significantly longer than those that did not receive the treatment. This showed that adding pig sugars to tumor cells could successfully provoke a strong enough immune response to impact survival.

However, researchers caution that positive results in animals don’t always translate directly to humans. Further clinical trials are essential to confirm safety and effectiveness in people before this method could become a standard cancer therapy.

Potential Advantages

One major advantage of this strategy is that it does not rely on the tumor’s natural ability to display immune targets. Even cancers that usually hide from the immune system can be made visible by coating them with pig sugars. This approach could also work across many different types of cancer, because it does not depend on a specific tumor mutation or characteristic—it simply forces the immune system to see the cancer as foreign. Another benefit is the use of the Newcastle disease virus, which is nonpathogenic to humans. This makes it a safer delivery tool compared to some other viruses used in cancer research.

Finally, because the immune system already has strong pre-existing antibodies against pig sugars, this method could trigger a fast and powerful immune response against tumors without needing long preparation or special immune training.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite its promise, the approach faces important challenges. One concern is the risk of overactivating the immune system, which could cause dangerous side effects like autoimmunity or cytokine storms, where the immune response becomes too aggressive and harms healthy tissues. Another challenge is making sure the virus infects only cancer cells, without accidentally targeting healthy cells, which could lead to unwanted damage. It’s also unclear how durable the immune response will be—will the immune system “remember” the tumor after the initial attack, or will cancer cells eventually escape again?

Moving from lab experiments to real-world use will require scaling up virus production safely and ensuring precise delivery in human patients, which can be complex and costly.

Next Steps: What Comes After Animal Trials

Human clinical trials are already underway to test whether this virus-based strategy is safe and effective in people with cancer. Researchers now need to carefully determine the optimal virus dose, monitor for any unexpected side effects, and figure out which cancer types respond best to this immune attack approach. Even if early results are positive, there will still be important regulatory hurdles to clear before this treatment can be widely used in clinics. Approval agencies will require extensive safety, manufacturing, and long-term follow-up data before granting permission for general patient use.

You Can Watch More on OncoDaily Youtube TV

Written by Toma Oganezova, MD

FAQ

What is the new cancer immunotherapy approach discussed?

It involves engineering tumor cells to display pig-specific sugars (α-gal), triggering an immune attack against the cancer.

How does the immune system recognize the modified cancer cells?

The immune system already has antibodies against pig sugars, so it sees the coated tumor cells as foreign invaders.

What virus is used to deliver pig sugars to tumor cells?

The Newcastle disease virus, which is harmless to humans, is genetically engineered to deliver the α-gal sugars.

Has this method been tested yet?

Yes, early testing in monkeys showed improved survival compared to untreated controls.

What are the advantages of this therapy?

It can make hidden cancers visible to the immune system and works independently of specific tumor mutations.

Are there risks to this strategy?

Possible risks include immune overactivation (cytokine storms) and the need for precise targeting to avoid harming healthy tissues.

When will this therapy be available for patients?

Human clinical trials are currently underway, but widespread use will depend on proving safety and efficacy.

Could this therapy treat all cancers?

Potentially, since it doesn't rely on specific tumor markers, but more research is needed to confirm effectiveness across cancer types.

Why was the Newcastle disease virus chosen?

It’s safe for humans, easy to engineer, and can effectively deliver genetic material to tumor cells.

What happens next in research?

Researchers will optimize dosing, monitor side effects, and work toward meeting regulatory requirements for broader clinical use.

-

Challenging the Status Quo in Colorectal Cancer 2024

December 6-8, 2024

-

ESMO 2024 Congress

September 13-17, 2024

-

ASCO Annual Meeting

May 30 - June 4, 2024

-

Yvonne Award 2024

May 31, 2024

-

OncoThon 2024, Online

Feb. 15, 2024

-

Global Summit on War & Cancer 2023, Online

Dec. 14-16, 2023