Spicy food refers to dishes prepared with chili peppers (Capsicum spp.), hot sauces, chili powders, and other seasonings rich in capsaicinoids, especially capsaicin, the compound responsible for the burning “heat” sensation in the mouth and on mucous membranes. These foods are consumed daily by large populations in Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East, where they form a core part of traditional diets, often eaten multiple times per day alongside rice, noodles, or tortillas. Qunran Xiang, Oct. 2021, Science Direct.

Recent large cohort studies and meta‑analyses (2019–2025) show that the relationship between spicy food and gastrointestinal (GI) cancer is not a simple “yes, spicy food causes cancer” or “no, it is safe”. Instead, the evidence indicates that the cancer risk is highly organ‑specific (e.g., increased risk in the esophagus in some settings, but neutral or reduced risk in the colon), dose‑dependent (higher risk with very frequent, very hot chili intake), and modulated by region, cooking practices, and lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol, and salt intake.

Photo: Depositphotos

The current scientific consensus is that, for most people, moderate spicy food consumption as part of a balanced diet is unlikely to be a major driver of GI cancer, but very high intake may modestly elevate risk for certain cancers, particularly in high‑risk populations and when combined with other carcinogenic exposures.Wing Ching , Int J Epidemiol. 2021 Jan.

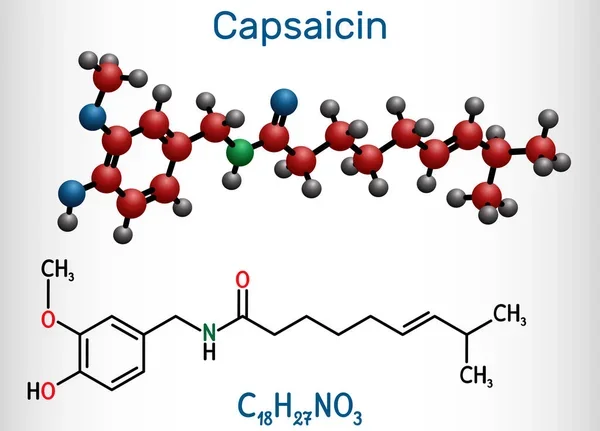

The Bioactive Ingredient: Capsaicin

Capsaicin, the main pungent compound in chili peppers, exerts complex, sometimes opposing effects in the gastrointestinal tract, acting through transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), a key pain and heat sensor on epithelial and nerve cells. At moderate doses, capsaicin can activate TRPV1 in a way that promotes apoptosis (programmed cell death) in precancerous and cancer cells, reduces inflammation, and lowers oxidative stress by modulating signaling pathways such as NF‑κB and STAT3, which may explain the protective associations seen in some large cohort studies, particularly for colorectal and esophageal cancer. Rebeca Juárez-Contreras , Front Nutr. 2025 May

However, at very high or chronic doses, capsaicin’s effects can shift toward pro‑inflammatory and pro‑proliferative patterns, causing persistent epithelial injury, increased oxidative DNA damage, and enhanced activity of pro‑cancer transcription factors, especially when combined with other risk factors like alcohol, smoking, or H. pylori infection.

Photo: Depositphotos

Recent mechanistic and experimental reviews (2019–2025) emphasize that capsaicin is not simply a carcinogen or a chemopreventive agent; instead, it likely follows a U‑shaped or non‑linear dose–response curve in the GI tract, where low–moderate intake may be protective or neutral, but very high intake could be harmful in certain tissues and populations. This dose‑ and tissue‑dependence is a key reason why epidemiological studies report mixed results, with some showing increased risk, others decreased risk, and many showing no clear association across the gastrointestinal tract.

Organ‑by‑Organ Analysis of Cancer Risk (2019–2025)

Modern evidence suggests that the effect of spicy food (defined as chili peppers, hot sauces, and very pungent spice blends) on gastrointestinal cancer is not uniform across the GI tract, but varies by organ, geographical region, and exposure level. Below is a concise, organ‑specific review of findings from large cohort studies, meta‑analyses, and high‑quality case‑control studies published between 2019 and 2025, with a focus on esophageal, gastric, and colorectal sites.

Esophageal Cancer: Conflicting but Stronger Signal

Overall, the data on esophageal cancer are the most consistent in pointing to a meaningful association with spicy food, but the direction differs by study design and region. In large Chinese cohorts, frequent spicy food intake is linked to lower esophageal cancer risk, especially in non‑smokers and non‑drinkers. In contrast, meta‑analyses focusing on chili pepper intake generally report an increased risk, particularly in Asian populations.

The evidence on spicy food and esophageal cancer from studies published between 2019 and 2025 shows conflicting but meaningful patterns. In a large Chinese prospective cohort (Chan WC et al., Int J Epidemiol 2021), adults who consumed spicy food 6–7 days per week had a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.81 (95% CI: 0.71–0.93) for esophageal cancer (mostly esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, ESCC) compared to those who never ate spicy food, indicating that higher spicy food intake was associated with lower esophageal cancer risk, especially among non‑smokers and non‑drinkers, and this protective effect remained after adjusting for major confounders.

In contrast, a 2022 meta‑analysis of 14 case–control studies (Chen C et al., Front Nutr 2022) found that high chili pepper intake was associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer, with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.71 (95% CI: 1.54–4.75) for high vs. low chili pepper consumption; this elevated risk was most pronounced in Asian populations, while the association was weaker or absent in European and South American studies.

Synthesizing these findings, in high‑risk ESCC regions where spicy food is a regular dietary component (such as parts of China), moderate daily intake may be linked to lower risk, possibly due to capsaicin’s anti‑inflammatory and metabolic effects. However, very high chili intake, particularly when combined with extremely hot foods and beverages, smoking, and alcohol, appears to increase esophageal cancer risk, likely by promoting chronic mucosal injury, oxidative stress, and pro‑inflammatory signaling in the esophagus.

You Can Also Read Memory of Robert Kardashian: His Courageous Battle with Esophageal Cancer by OncoDaily

Gastric (Stomach) Cancer: Weak or Neutral Link

For gastric cancer, the evidence from recent large studies is much less consistent, and any association with spicy food is generally weak, non‑significant, or highly confounded by other factors (especially H. pylori, salt, smoking, and alcohol).

Recent evidence on spicy food and gastric cancer shows a weak and inconsistent association across studies. In a large Chinese prospective cohort (Chan WC et al., Int J Epidemiol 2021), eating spicy food 6–7 days per week was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.89 (95% CI: 0.80–0.99) for stomach cancer compared to never eating spicy food, suggesting a weak inverse association; however, this link largely disappeared after excluding the first 3 years of follow‑up, raising the possibility that it was driven by reverse causation (e.g., people with early symptoms reducing spicy food) or confounding by other factors like smoking and alcohol intake.

In contrast, a 2022 meta‑analysis of 14 case–control studies (Chen C et al., Front Nutr 2022) found that high chili pepper intake versus low intake was associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.77 (95% CI: 0.84–3.73) for gastric cancer, which is not statistically significant, indicating that the data do not support a clear, independent link between chili pepper consumption and gastric cancer risk; the meta‑analysis also noted large geographic differences and the major role of confounding factors such as salt, H. pylori infection, smoking, and regional diet patterns.

Putting these together, current high‑quality evidence does not support a strong causal relationship between spicy food and gastric cancer. Any observed associations (whether slightly protective or slightly harmful) are small, non‑significant in meta‑analysis, and heavily influenced by confounding. For most people, moderate intake of spicy food as part of a balanced diet is unlikely to be a major independent risk factor for stomach cancer, with established factors like H. pylori, salt, smoking, and processed meats playing a far more important role.

Colorectal Cancer and Polyps: Mixed, with New Polyp Data

Colorectal cancer risk shows a similarly weak and inconsistent association with spicy food in recent large cohorts. However, a 2025 Chinese study provides new insight by distinguishing colorectal polyps (benign precursors) from true adenomas (higher‑risk precursors).

Recent evidence on spicy food and colorectal cancer shows a neutral to slightly inverse overall association, with new data highlighting a possible link to polyps in high‑risk groups. In a large Chinese prospective cohort (Chan WC et al., Int J Epidemiol 2021), people who ate spicy food 6–7 days per week had a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.90 (95% CI: 0.80–1.01) for colorectal cancer compared to those who never ate it, suggesting a weak inverse association, mainly driven by rectal cancer; however, this association became much weaker after excluding the first few years of follow‑up, indicating that it may be partly due to reverse causation or confounding by lifestyle factors.

A 2022 meta‑analysis (Chen C et al., Front Nutr 2022) of 14 case control studies found that high chili pepper intake versus low intake was associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.62 (95% CI: 0.26–1.47) for colorectal cancer, which is not statistically significant, confirming that there is no clear, independent association between chili pepper consumption and colorectal cancer risk in the available data.

More recently, a 2025 cross‑sectional cohort in a high‑risk Chinese population (Hu P et al., Front Nutr 2025) found that the highest quartile of spicy food intake (compared to the lowest quartile) was associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.24 (95% CI: 1.13–1.37) for colorectal polyps, but not with adenomas, suggesting that high spicy food intake is independently linked to a higher prevalence of colorectal polyps without the same clear association with higher‑risk adenomas.

Interpreting these findings together, in general populations, spicy food does not appear to be a major driver of colorectal cancer, and some data even suggest a modest protective effect, especially for rectal cancer. However, in high‑risk polyp cohorts, very high intake may promote the development of colorectal polyps, likely reflecting early mucosal changes, while not showing a strong link to advanced neoplasia. This suggests that excessive spicy food may contribute to early polyp formation, but is unlikely on its own to be a primary cause of colorectal cancer in most people.

Moderating Factors: Why Results Vary

The relationship between spicy food and GI cancer risk is not uniform, because it is strongly modified by dose, pattern of consumption, and the broader lifestyle and dietary context. Recent large cohort and meta‑analysis models show that very high intake of chili peppers daily consumption of very hot, strongly spiced dishes tends to be associated with a higher risk of esophageal cancer, especially in high‑risk populations, while moderate spicy food intake in some cohorts (e.g., 3–6 days/week) shows a weakly protective signal, particularly for esophageal and colorectal cancers, supporting a U‑shaped dose response curve where both very low and very high intake (especially extreme chili loads) may be unfavorable, while moderate intake carries neutral or slightly beneficial net effects.

Another key factor is how spicy food interacts with other major risk behaviors. In the same studies, the inverse association between spicy food and esophageal cancer is strongest among never‑smokers and never‑drinkers, and the apparent positive association in other settings often disappears after adjusting for tobacco and alcohol; this shows that spicy food does not act in isolation, but its effect is amplified or masked by these powerful carcinogens.

Finally, regional dietary patterns heavily confound the picture: in many parts of Asia and Africa, high chili intake goes hand‑in‑hand with high‑salt, smoked, or preserved foods and low vegetable intake, whereas in some European and Latin American settings, spicy food is often part of diets higher in vegetables, legumes, and olive oil, and lower in smoking and alcohol, which helps explain the divergent regional results in meta‑analyses.

Clinical and Public Health Perspective

Current evidence does not support a simplistic “spicy food = cancer” message, but rather a nuanced, risk‑stratified view. For most people who enjoy spicy food in moderation as part of a balanced diet (e.g., a few spicy meals per week, with plenty of vegetables, without scalding‑hot temperatures), the available data from prospective cohorts show no convincing increase in overall gastrointestinal cancer risk; if anything, moderate intake may be associated with slightly lower risk for some cancers, such as esophageal and colorectal cancer, in certain populations [Chan et al., Int J Epidemiol 2021][Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022][Hu et al., Front Nutr 2025].

However, in high‑risk subgroups particularly smokers, heavy alcohol users, and individuals with long‑standing GERD, Barrett’s esophagus, or a strong family history of esophageal cancer very high intake of very hot chili‑based dishes, especially when combined with scalding‑hot liquids, may modestly increase the risk of esophageal cancer [Chan et al., Int J Epidemiol 2021][Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022][Chan et al., Int J Epidemiol 2021]. In these cases, a reasonable clinical precaution is to reduce the frequency and intensity of spicy foods, avoid extremely hot serving temperatures, and focus on a predominantly plant‑based, low‑salt, low‑processed‑food pattern [Chan et al., Int J Epidemiol 2021][Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022].

For the general healthy population, enjoying spicy food in moderation does not appear to be a major driver of GI cancer, and the priority for prevention should remain on established factors: tobacco, alcohol, obesity, low fiber, high processed/red meat, and uncontrolled H. pylori and reflux disease [Chan et al., Int J Epidemiol 2021][Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022][Chan et al., Int J Epidemiol 2021].

You Can Also Read Does Processed Meat Cause Cancer? Myths and Facts by OncoDaily

Written by Aharon Tsaturyan, MD, Editor at OncoDaily Intelligence Unit

FAQ

Is spicy food a proven cause of gastrointestinal cancer?

Recent high‑quality evidence shows there is no simple rule that “spicy food = GI cancer”; instead, the relationship is organ‑specific and depends heavily on dose, region, and other lifestyle factors, with some studies even linking moderate spicy food to lower risk for certain cancers [Chan et al., IJE 2021; Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022].

Does spicy food increase the risk of esophageal cancer?

Meta‑analyses, particularly in Asian populations, suggest that very high chili intake is associated with a higher risk of esophageal cancer, but in large Chinese cohorts, frequent spicy food intake is actually linked to lower risk, especially among non‑smokers and non‑drinkers, highlighting the role of context and dose [Chan et al., IJE 2021; Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022].

Can spicy food cause stomach cancer?

Current evidence does not support a strong independent causal link between spicy food and gastric cancer; any observed associations are generally weak, non‑significant in meta‑analyses, and largely explained by confounding factors like H. pylori infection, high salt intake, and smoking rather than chili itself [Chan et al., IJE 2021; Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022].

Is there a safe level of spicy food consumption?

The relationship between spicy food and GI cancer appears to follow a U‑shaped curve, where very low and very high chili intake may carry higher risk in some settings, while moderate intake (a few times per week, not extreme “fire‑hot”) is generally neutral or slightly protective, especially in balanced diets [Chan et al., IJE 2021; Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022].

Does spicy food interact with other cancer risk factors?

Spicy food does not act in isolation; its effect is strongly modified by smoking, alcohol, and GERD, with the inverse association with esophageal cancer being strongest in never‑smokers/never‑drinkers and the positive association often disappearing after adjusting for tobacco and alcohol [Chan et al., IJE 2021; Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022].

Is it the spice itself or the temperature that matters more?

The biggest concern for esophageal cancer may be less about capsaicin and more about very hot (scalding) food and drinks, which cause repeated mucosal injury and chronic inflammation, independent of spiciness, so “cooling down” the serving temperature is often more important than just reducing chili [Chan et al., IJE 2021; Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022; WHO/thermal injury guidance].

Is capsaicin carcinogenic or protective?

Capsaicin is a double‑edged sword: at moderate doses it can promote apoptosis and reduce inflammation, potentially protecting against esophageal and colorectal cancer, but at very high or chronic doses it may shift toward pro‑inflammatory and pro‑proliferative effects, especially when combined with other carcinogens like alcohol or tobacco [Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022; Rebeca Juárez‑Contreras, Front Nutr 2025].

Does spicy food affect colorectal polyps and cancer?

In high‑risk cohorts, very high spicy food intake has been associated with higher prevalence of colorectal polyps, but not with higher‑risk adenomas, suggesting it may contribute to early polyp formation without a clear link to advanced neoplasia, while large prospective studies show only a weak or neutral association with colorectal cancer itself [Hu et al., Front Nutr 2025; Chan et al., IJE 2021; Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022].

Why do studies on spicy food and cancer seem to disagree?

The apparent conflicts reflect differences in study design, region, and dietary patterns: in Asia/Africa, high chili intake often occurs with high‑salt, smoked foods, and low vegetable intake, whereas in some Latin American and Southern European settings it is part of diets richer in plant foods, which explains the divergent findings across populations [Chan et al., IJE 2021; Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022].

Should people at high risk of GI cancer stop eating spicy food?

For most people eating spicy food in moderation as part of a balanced, plant‑rich diet, it is unlikely to be a major driver of GI cancer; the main modifiable risk factors remain tobacco, alcohol, obesity, low fiber, high processed/red meat, and uncontrolled reflux, with very hot spicy food being a secondary, manageable risk in high‑risk individuals [Chan et al., IJE 2021; Chen et al., Front Nutr 2022].