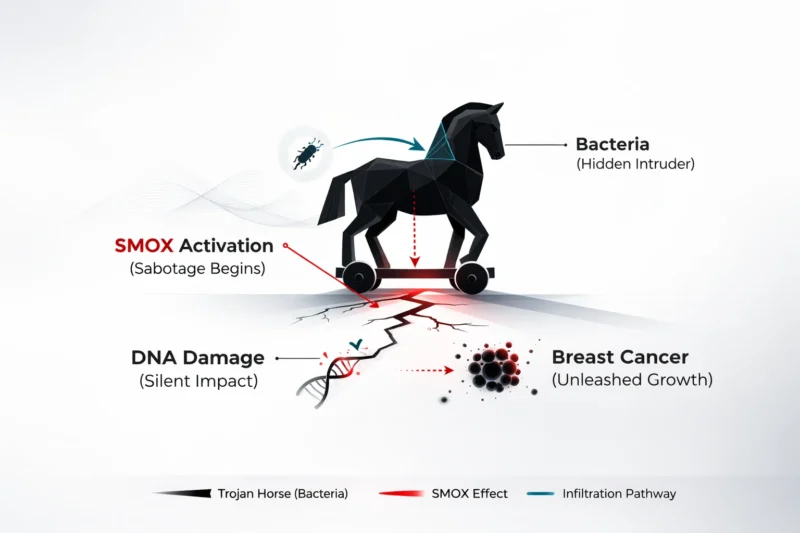

SMOX appears to function as a central molecular “node” in breast oncogenesis influenced by multiple pathogenic microbes. These findings suggest that pharmacologic inhibition of SMOX may represent a promising intervention strategy for breast cancer patients affected by microbial dysbiosis.

Rethinking the Drivers of Breast Cancer

Breast cancer research has increasingly moved beyond tumor cells alone to examine the broader biological environment that shapes disease behavior. One of the most rapidly expanding frontiers is the human microbiome, the community of microorganisms that live in and on the body. While the gut microbiome is best known for its role in digestion and immunity, growing evidence indicates that microbes can influence distant tissues and contribute to cancer-related inflammation and metabolic changes. A new study from the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center offers important insight into how specific pathogenic bacteria may promote breast cancer development and progression through a metabolic enzyme called spermine oxidase, or SMOX.

The Study at a Glance

Investigators led by Dipali Sharma, Ph.D., professor of oncology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, found that exposure to pathogenic bacteria including enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and toxin-producing Escherichia coli significantly increased SMOX activity in breast cancer models. This elevation was associated with oxidative stress, DNA damage, accelerated tumor growth, and increased metastatic potential in both laboratory and animal experiments. The work, published in Cancer Research, establishes a mechanistic link between microbial dysbiosis and breast cancer aggressiveness and points to SMOX as a potential therapeutic target.

Why SMOX Matters in Cancer Biology

SMOX is part of polyamine metabolism, a set of biochemical pathways that regulate molecules involved in cell growth and survival. Under normal conditions, these pathways are tightly controlled. The Johns Hopkins team demonstrated that when certain pathogenic microbes are present, SMOX becomes overactivated. This overactivation leads to the production of reactive oxygen species, highly reactive molecules capable of damaging DNA. When DNA damage accumulates, genomic instability increases, and cells become more likely to acquire tumor-promoting mutations and behaviors. In this way, microbial activation of SMOX can create a biochemical environment that favors tumor initiation and progression.

Pathogenic Bacteria and the Triggering of a Harmful Cascade

A central focus of the research was enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis, a strain known to produce a powerful toxin that can reshape bacterial communities and contribute to cancer-promoting inflammation. When breast cancer cells or mouse mammary tissue were exposed to ETBF or its toxin, SMOX levels rose sharply. This change was accompanied by increased oxidative stress and markers of DNA injury, suggesting that the bacterial toxin initiates a direct molecular cascade that can push breast tissue toward malignant behavior.

Notably, the effect was not unique to ETBF. The researchers observed similar SMOX induction when cells were exposed to Fusobacterium nucleatum and toxin-producing E. coli. In contrast, nonpathogenic bacteria did not produce the same response, supporting the conclusion that specific harmful microbial features, rather than bacteria in general, drive this mechanism.

Inflammation, Cytokines, and a Self-Perpetuating Loop

The study also revealed that bacterial exposure increases inflammatory signaling, particularly through cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. These cytokines not only reflect inflammation but also actively amplify SMOX expression and activity. The result is a reinforcing cycle in which pathogenic bacteria stimulate inflammation, inflammation increases SMOX, SMOX generates oxidative stress, and oxidative stress causes DNA damage that supports tumor growth and spread. Deeptashree Nandi, Ph.D., the study’s first author, described this as a self-perpetuating loop that helps explain how microbial imbalance can translate into sustained cancer-promoting pressure within tissues.

Blocking SMOX: A Potential Therapeutic Strategy

To determine whether interrupting this pathway could reduce cancer-promoting effects, the researchers tested two SMOX inhibitors, MDL72527 and SXG-1, in breast cancer cell and animal models. In both settings, inhibition of SMOX reduced DNA damage markers and suppressed tumor progression even when pathogenic bacteria were present. In mouse experiments, animals colonized with ETBF developed more and faster-growing mammary tumors than uninfected controls, but treatment with SMOX inhibitors resulted in smaller tumors, fewer metastases, and lower levels of oxidative DNA damage.

These findings support the concept that pharmacologic targeting of SMOX could counteract microbe-driven tumor biology. They also suggest that SMOX inhibition may be most relevant for patients whose tumors develop in the context of microbial dysbiosis, where pathogenic bacteria or their products may be contributing to inflammation and oxidative DNA injury.

A Shared Mechanism Across Multiple Microbes

An important implication of the study is the observation that multiple distinct bacterial species converge on the same molecular hub. Beyond B. fragilis, F. nucleatum, and E. coli, the researchers also reported that Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture extracts induced SMOX upregulation and DNA injury in breast cancer cells. This cross-species convergence suggests that SMOX may represent a common pathway through which diverse microbes influence cancer behavior, increasing its relevance as a target in broader microbiome-associated cancer research.

Clinical Significance and Future Directions

The study raises the possibility that measuring microbial composition or SMOX activity could help identify individuals at increased risk for aggressive breast cancer. It also supports future efforts to integrate microbiome-informed strategies into oncology, including targeted metabolic interventions that blunt microbe-driven inflammation and DNA damage. The researchers are now exploring SMOX inhibitors as potential adjuncts to standard therapies and investigating how microbe-induced inflammatory signaling shapes immune responses within tumors, a key question for improving outcomes and tailoring treatment.

More posts about sceince in OncoDaily

Written by Nare Hovhannisyan, MD