Douglas Flora: The messy truth behind healthcare’s coming AI adoption

Douglas Flora, Executive Medical Director of Oncology Services at St. Elizabeth Healthcare and ACCC President-Elect, shared a post on LinkedIn:

“Like the automobile in 1900, AI in medicine arrives first as a curiosity, then a threat, before eventually revealing itself as a partner. It disrupts established patterns of work while promising to solve intractable problems. It requires reskilling rather than replacement. And it will likely create forms of medical practice we cannot yet fully envision.

When we look at how communities navigate technological transitions, we find a consistent truth: the most successful adaptations occur not when we resist change entirely, nor when we surrender to it blindly, but when we deliberately shape it to enhance what humans do best. The carriage makers who prospered were those who saw automobiles not as the enemy of transportation, but as its evolution.

So too with AI in medicine. The algorithms that analyze images, suggest treatment pathways, and synthesize literature are not the end of medical expertise but its amplification.

They will change the landscape of care just as automobiles changed city streets – clearing away the equivalent of manure and dead horses: the administrative burden, the information overload, the cognitive limitations that constrain even the most brilliant clinicians.

How Horse Manure Made the Modern World: The Messy Truth Behind Healthcare’s Coming AI Adoption

‘If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.’ – Henry Ford.

History’s greatest transformations often arrive not with fanfare but with suspicion. Henry Ford understood this paradox perfectly, that people rarely envision revolutionary change until they’re standing in the midst of it.

They don’t ask for automobiles; they ask for faster horses. They seek improvements to what they know, not replacements for what they cannot yet imagine.

This insight applies to every technological transition throughout history. It reveals the natural human tendency to frame the future in terms of the familiar present, even when that present is fundamentally unsustainable. Even when we’re literally drowning in the consequences of our current solutions.

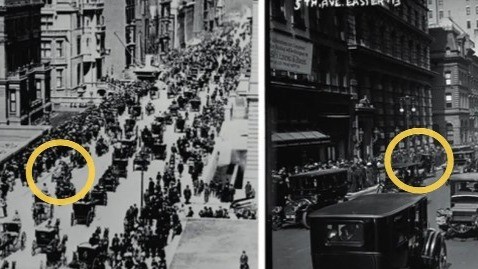

In the dawn of the twentieth century, New York City moved to the rhythm of hoofbeats. The city’s lifeblood – its commerce, its transportation, its daily pulse – flowed through the veins of over 100,000 working horses that pulled its streetcars, delivered its goods, and carried its citizens.

Ford’s ‘faster horses’ weren’t just a hypothetical preference; they represented the actual solution most urban planners and transportation experts were pursuing. More horses. Better horses. Faster horses. Despite mounting evidence that the entire horse-based system was collapsing under its own waste.

Each horse produced between fifteen and thirty-five pounds of manure daily. Mountains of waste piled on streets, attracted flies, spread disease, and created what contemporary observers called the Great Horse Manure Crisis. When it rained, streets became rivers of filth.

When summer heat baked the city, the stench became unbearable. When horses died, as they frequently did from overwork and disease, their carcasses had to be removed quickly before decay set in.

In 1898, urban planners from around the world gathered in New York for what was to be a ten-day conference. They disbanded after just three days, unable to solve what seemed the most pressing urban problem of their time: how to manage the consequences of horse-powered cities.

The situation appeared unsustainable, yet entirely necessary. Who could imagine cities without horses? Exactly as Ford would later observe, they could envision faster, better horses – but not a world beyond horses altogether.

Then came the outsiders, the mechanical interlopers. The first automobiles that sputtered onto New York’s streets around 1900 resembled strange, noisy carriages that moved without visible means of propulsion.

They backfired and frightened horses, broke down unpredictably, and required specialized knowledge to operate. They were expensive toys for the wealthy, unreliable and dangerous.

For those whose lives were intertwined with horses, these mechanical contraptions represented not progress but threat. Not evolution but extinction. They didn’t see salvation from the manure crisis; they saw displacement. They didn’t recognize a solution; they recognized only the end of everything they knew.

Ford’s insight manifested in their resistance – people don’t reject new technologies because they’re irrational; they reject them because they cannot yet see how these strange new tools connect to their existing values, skills, and identities.

The resistance was immediate and multifaceted. Cities passed ordinances requiring automobiles to travel at walking pace. Some municipalities demanded that a person with a red flag walk ahead of any motorcar to warn pedestrians and horses. Newspapers published lurid accounts of automobile accidents.

Stable owners, feed merchants, carriage makers, and teamsters saw in these machines the end of a way of life, the erasure of skills honed over generations, the destruction of businesses built through decades of work.

We see the same pattern repeating now in oncology departments and executive boardrooms, the instinctive protection of established expertise against algorithmic interlopers. The reasonable fear that automation might replace not just tasks but identity.

The worry that what took years to learn might be rendered obsolete by code written in months. Just as the blacksmiths and carriage makers asked for better tools to support their existing craft, healthcare professionals ask for better support within familiar paradigms, not revolutionary change to those paradigms themselves.

But the story of the automobile did not end with resistance. It pivoted toward adaptation.

By 1915, a transformation was underway that would have seemed impossible just fifteen years earlier. The very problems created by horse-dependent cities – the waste, the disease, the limited range, the vulnerability to weather – made automobiles increasingly attractive solutions. Innovation accelerated. Henry Ford’s production techniques made cars more affordable. Roads improved. Reliability increased.

And something unexpected happened to employment. Rather than collapsing, it evolved. Former carriage makers began crafting auto bodies. Blacksmiths retrained as mechanics. Harness makers found new applications for their leatherworking skills in upholstery. Entire new industries emerged: gas stations, repair shops, roadside restaurants, motels, highway construction.

What had seemed like technological disruption revealed itself as technological redirection. Skills transferred. New specialties emerged. And the ecosystem didn’t disappear, it transformed.

By the 1920s, automobiles had not only replaced horses in American cities but had created more jobs than they eliminated. The urban landscape changed; stables became garages, watering troughs gave way to filling stations, and manure-filled streets transformed into paved roads. The city itself adapted to a new technological reality, becoming cleaner, more mobile, and more connected.

This pattern of resistance, adaptation, and ultimately transformation offers us something valuable as we face today’s technological inflection points. The parallels to healthcare’s AI moment are striking.

Like the automobile in 1900, AI in medicine arrives first as a curiosity, then a threat, before eventually revealing itself as a partner. It disrupts established patterns of work while promising to solve intractable problems. It requires reskilling rather than replacement. And it will likely create forms of medical practice we cannot yet fully envision.

When we look at how communities navigate technological transitions, we find a consistent truth: the most successful adaptations occur not when we resist change entirely, nor when we surrender to it blindly, but when we deliberately shape it to enhance what humans do best.

The carriage makers who prospered were those who saw automobiles not as the enemy of transportation, but as its evolution.

So too with AI in medicine. The algorithms that analyze images, suggest treatment pathways, and synthesize literature are not the end of medical expertise but its amplification.

They will change the landscape of care just as automobiles changed city streets – clearing away the equivalent of manure and dead horses: the administrative burden, the information overload, the cognitive limitations that constrain even the most brilliant clinicians.

And just as New York in 1925 was not without drivers, navigators, and mechanics, healthcare’s future will not be without doctors, nurses, and specialists. Their roles will evolve, certainly. Their focus will shift toward the uniquely human elements of care. But their purpose – the healing relationship at medicine’s core – will remain essential.

The reluctant revolution of the automobile offers us this wisdom:

What first appears as replacement often becomes enhancement.

What threatens expertise frequently ends up extending it.

And the skills that seem most endangered sometimes transform into those most valued in the new landscape.

The question is not whether change will come, but how we will navigate it when it does.”

More posts featuring Douglas Flora.

-

Challenging the Status Quo in Colorectal Cancer 2024

December 6-8, 2024

-

ESMO 2024 Congress

September 13-17, 2024

-

ASCO Annual Meeting

May 30 - June 4, 2024

-

Yvonne Award 2024

May 31, 2024

-

OncoThon 2024, Online

Feb. 15, 2024

-

Global Summit on War & Cancer 2023, Online

Dec. 14-16, 2023