Immunotherapy has fundamentally changed cancer treatment, yet its clinical benefit remains highly heterogeneous. While some patients experience deep and durable responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors, many derive limited or no benefit despite receiving the same agents. This variability reflects differences in tumor biology and immune engagement rather than inconsistency in drug activity. Immune checkpoint blockade depends on the presence of an immunogenic tumor, effective antigen presentation, and a functional antitumor immune response—conditions that are not universally present.

Recognition of this heterogeneity has driven a shift away from a “one-drug-fits-all” approach toward biomarker-guided immunotherapy. PD-L1 expression, microsatellite instability (MSI-H/dMMR), and tumor mutational burden (TMB) are now widely used in clinical decision-making. Importantly, these biomarkers assess distinct biological processes and are not interchangeable. Misinterpretation—particularly treating a single biomarker as a definitive predictor of benefit—remains a common challenge in daily practice, especially among trainees.

What Are the Signs That Immunotherapy Is Working?

PD-L1 Expression: The Most Used—but Least Perfect—Biomarker

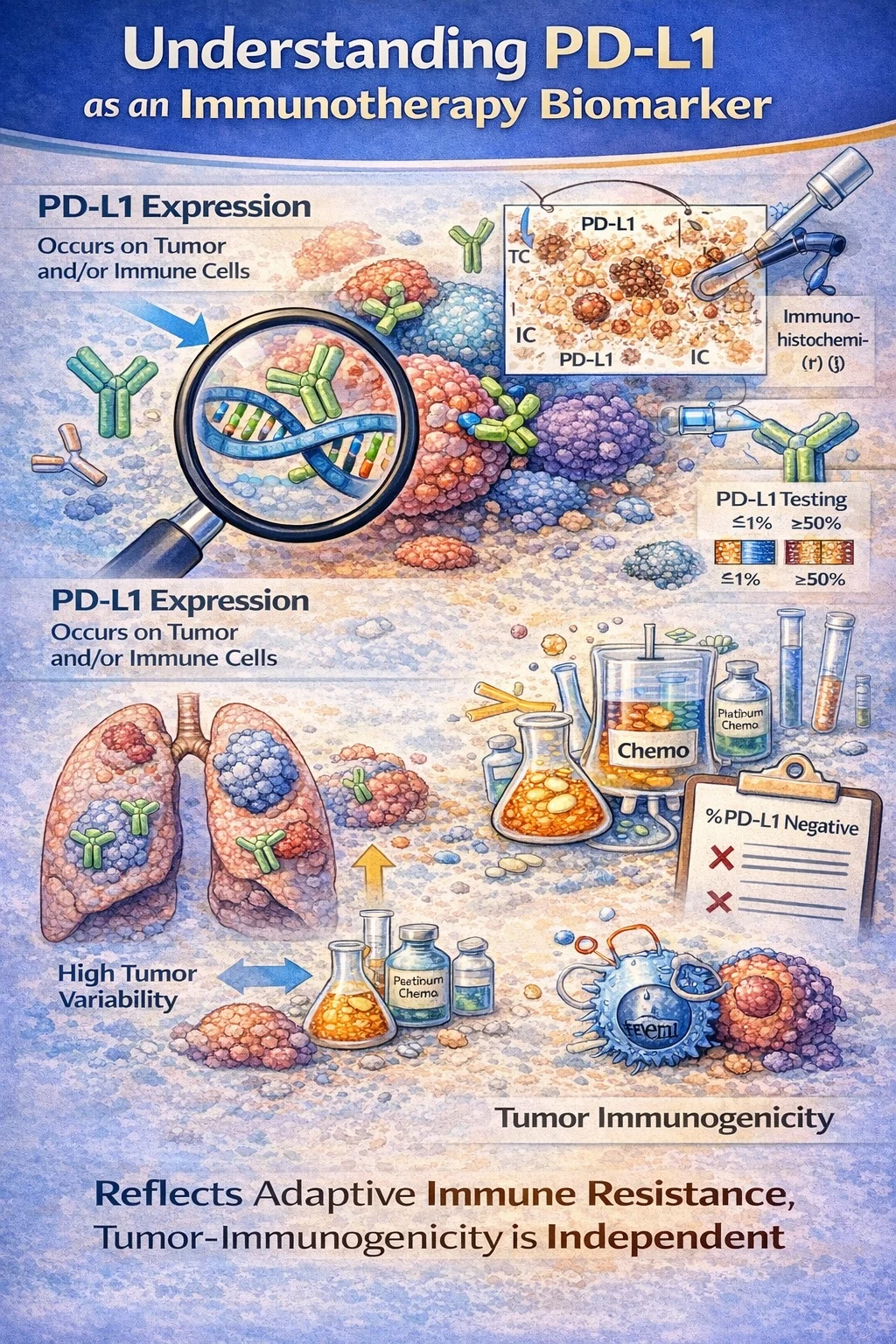

PD-L1 expression is the most frequently used immunotherapy biomarker and reflects adaptive immune resistance within the tumor microenvironment. It may be measured on tumor cells, immune cells, or both, depending on tumor type and scoring system. PD-L1 does not measure intrinsic tumor immunogenicity; rather, it reflects an immune interaction at a specific moment in time.

PD-L1 testing is performed using immunohistochemistry (IHC), but interpretation depends on the antibody clone and scoring system used in pivotal trials. Cutoffs such as ≥1% and ≥50% emerged from clinical trial design rather than biological thresholds.

In metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), PD-L1 is best understood as a treatment-selection biomarker, not an eligibility criterion. The KEYNOTE-024 trial demonstrated that patients with PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) ≥50% derive a significant overall survival benefit from pembrolizumab monotherapy compared with chemotherapy. However, subsequent trials clarified that PD-L1 negativity does not preclude immunotherapy benefit. In KEYNOTE-189, the addition of pembrolizumab to platinum-based chemotherapy improved overall survival regardless of PD-L1 expression, including in PD-L1–negative tumors.

Despite its utility, PD-L1 has substantial limitations. Expression can vary across tumor regions, change following chemotherapy or radiation, and differ between primary and metastatic sites. Consequently, PD-L1 negativity may falsely exclude patients who could benefit from immunotherapy, while high expression may provide false reassurance of response.

Microsatellite Instability (MSI): A Strong, Biology-Driven Predictor of Immunotherapy Response

MSI-H or mismatch repair–deficient (dMMR) tumors result from loss of DNA mismatch repair function, leading to widespread insertion–deletion mutations and frameshift errors. These alterations generate a high load of neoantigens, making MSI-H tumors highly visible to the immune system.

This biology explains the consistently high response rates of MSI-H/dMMR tumors to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Unlike PD-L1 expression, which is dynamic, MSI-H represents a stable genomic defect that continuously promotes immune recognition.

The clinical importance of MSI-H/dMMR was established through early multi-tumor analyses that led to the first FDA tissue-agnostic approval of pembrolizumab in 2017 for MSI-H/dMMR solid tumors. Subsequent disease-specific trials reinforced its predictive strength. In metastatic colorectal cancer, the KEYNOTE-177 trial showed that first-line pembrolizumab significantly improved progression-free survival compared with chemotherapy in MSI-H/dMMR disease, firmly establishing MSI status as a treatment-defining biomarker.

MSI testing is therefore essential in cancers where it is prevalent and clinically actionable, particularly colorectal, endometrial, and gastric cancers. Importantly, MSI-H tumors may respond to immunotherapy independent of PD-L1 expression, emphasizing that neoantigen load—not checkpoint ligand expression alone—drives benefit in this context.

Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB): Quantity Matters—but Quality Matters More

Tumor mutational burden quantifies the number of somatic mutations within a tumor genome and serves as an indirect estimate of neoantigen load. The underlying hypothesis is that tumors with more mutations are more likely to generate immunogenic antigens. However, TMB measures mutation quantity rather than functional immunogenic quality.

TMB is calculated using next-generation sequencing panels and reported as mutations per megabase. Values vary widely depending on panel size, sequencing depth, and bioinformatic filtering, limiting comparability across assays.

The FDA granted tissue-agnostic approval for pembrolizumab in TMB-high tumors (≥10 mut/Mb) based on KEYNOTE-158, in which patients with TMB-high tumors demonstrated higher response rates than those with lower TMB. Importantly, this approval applies to patients with previously treated disease and no satisfactory alternative options, and it does not imply uniform benefit across all tumor types.

TMB appears more informative in tumors with known mutagenic exposures, such as melanoma and smoking-associated NSCLC, but performs inconsistently in many other malignancies. Not all mutations produce effective neoantigens, and high TMB does not account for immune exclusion, T-cell exhaustion, or suppressive tumor microenvironments.

PD-L1 vs MSI vs TMB: How Do These Biomarkers Compare?

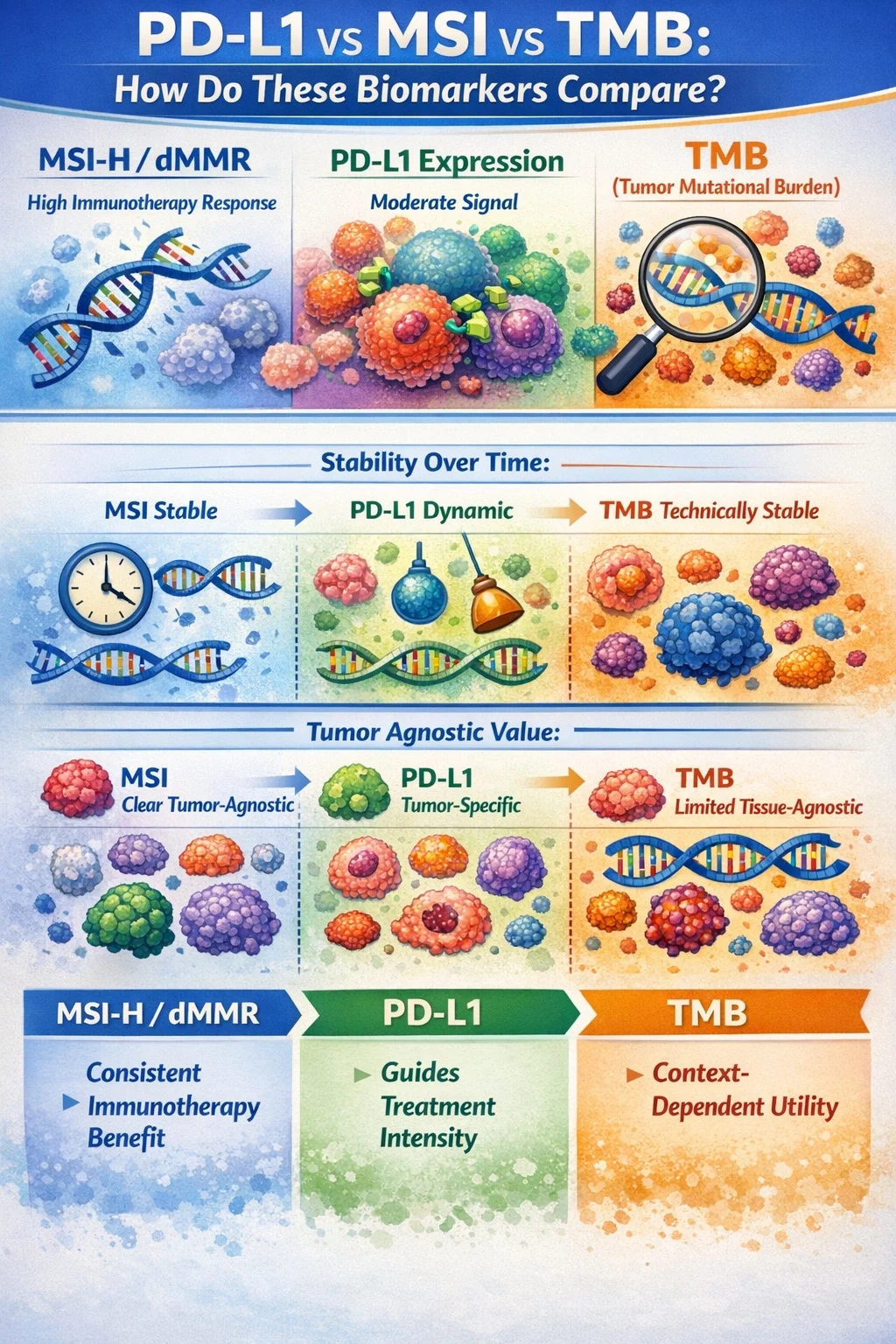

MSI-H/dMMR is the most robust and biologically grounded predictor of immunotherapy benefit, with consistent responses across tumor types and lines of therapy. PD-L1 provides a moderate, context-dependent signal that is most useful for guiding treatment intensity. TMB offers variable predictive value and is highly dependent on tumor type and assay methodology.

MSI status is stable over time, PD-L1 is dynamic, and TMB is technically stable but biologically incomplete. MSI has clear tumor-agnostic value, TMB has limited tissue-agnostic applicability, and PD-L1 remains tumor-specific.

Common Resident Pitfalls in Immunotherapy Biomarker Interpretation

Common mistakes include assuming PD-L1 negativity excludes immunotherapy, failing to test for MSI outside colorectal cancer, over-relying on TMB, and ignoring tumor-specific guideline requirements. These errors can lead to missed treatment opportunities or inappropriate therapy selection.

When Biomarkers Disagree: How to Think Clinically

Discordant immunotherapy biomarkers are common in daily oncology practice and often create uncertainty, particularly for trainees. Understanding the biological meaning behind each marker is essential to avoid over- or undertreatment and to make rational, patient-centered decisions.

A classic scenario is a PD-L1–negative but MSI-H tumor. In this setting, MSI-H status should take priority, as it reflects a high neoantigen load and robust immunogenicity independent of PD-L1 expression. These tumors consistently demonstrate meaningful responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors, and PD-L1 negativity should not deter immunotherapy use.

Conversely, high PD-L1 expression in microsatellite-stable tumors with low TMB may overestimate the likelihood of benefit. PD-L1 positivity alone does not guarantee immune responsiveness, particularly when the underlying mutational burden is low and antigen presentation is limited. In such cases, combination strategies or alternative systemic therapies may be more appropriate than immunotherapy monotherapy.

Another challenging situation is high TMB with poor clinical response. TMB reflects the quantity of mutations but not their immunogenic quality. Not all mutations generate effective neoantigens, and additional factors—such as immune exclusion, T-cell dysfunction, or suppressive tumor microenvironments—may limit response despite a high TMB score.

When biomarkers conflict, clinical decision-making should prioritize biological plausibility over numerical thresholds. MSI status generally carries the strongest predictive value, PD-L1 guides treatment intensity rather than eligibility, and TMB should be interpreted as a supportive, context-dependent marker. Tumor type, disease burden, line of therapy, and patient factors must be integrated into the final decision.

Key Takeaway Messages for Residents

- PD-L1 ≠ immunotherapy eligibility.

PD-L1 expression guides treatment strategy in selected cancers but does not determine whether immunotherapy can be given in many settings. - MSI-H tumors respond regardless of PD-L1 status.

MSI-H/dMMR reflects strong underlying tumor immunogenicity and is one of the most reliable predictors of immunotherapy benefit across tumor types. - TMB is supportive, not definitive.

High TMB may strengthen the rationale for immunotherapy but should never override stronger biological or guideline-based indicators. - Always interpret biomarkers in clinical context.

Tumor type, disease stage, prior therapy, and patient factors are as important as any single biomarker result.

You Can Watch More on OncoDaily Youtube TV