Alcohol is socially normalized, culturally embedded, and legally accessible almost everywhere. It is associated with celebration, relaxation, and connection. But biologically, alcohol behaves very differently.

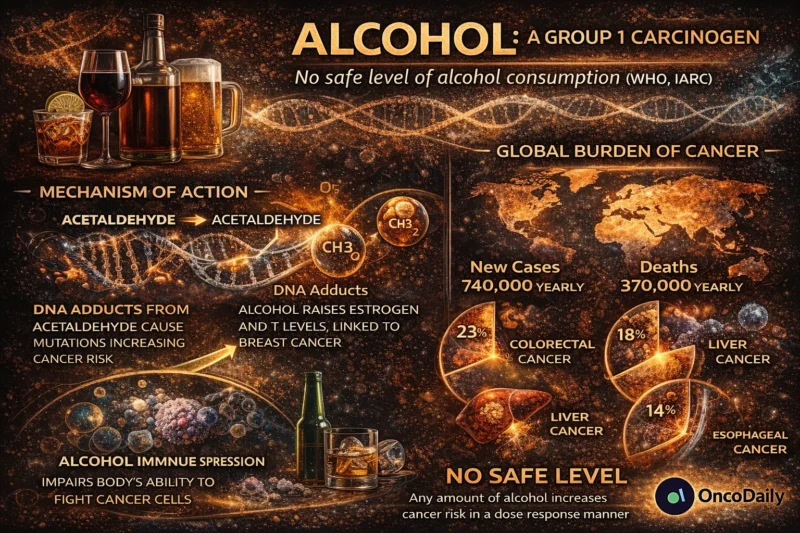

Alcohol is a Group 1 carcinogen, classified alongside tobacco and asbestos by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. There is no safe threshold for cancer risk. The relationship between alcohol and cancer is dose-dependent, but risk increases even at low levels of consumption.

The uncomfortable truth is this: alcohol directly contributes to DNA damage, hormonal dysregulation, oxidative stress, and impaired immune surveillance. These are not theoretical concerns. They are mechanistically established pathways backed by decades of epidemiologic and molecular research.

This is not about lifestyle shaming. It is about biology.

Alcohol and Cancer: The Epidemiologic Evidence

Globally, alcohol is responsible for approximately 740,000 new cancer cases annually, representing about 4% of all cancer diagnoses worldwide (Rumgay et al., 2021, Lancet Oncology). The strongest associations are seen in cancers of:

- Oral cavity

- Pharynx

- Larynx

- Esophagus

- Liver

- Colorectum

- Breast

A large pooled analysis published in The Lancet Oncology demonstrated a clear dose-response relationship, with risk increasing steadily as consumption rises (Rumgay et al., 2021). Importantly, even “moderate” drinking, defined in many societies as one drink per day, increases breast cancer risk (Bagnardi et al., 2015, Br J Cancer).

The idea that small amounts of alcohol are harmless in terms of cancer risk is not supported by current evidence.

Mechanism 1: Acetaldehyde, a Direct DNA Toxin

When alcohol (ethanol) is consumed, it is metabolized in the liver by alcohol dehydrogenase into acetaldehyde.

Acetaldehyde is the problem.

Acetaldehyde is mutagenic and carcinogenic. It forms DNA adducts, interferes with DNA repair mechanisms, and induces chromosomal instability (Seitz & Stickel, 2007, Nat Rev Cancer). Persistent DNA adduct formation leads to replication errors and accumulation of oncogenic mutations.

The carcinogenic classification by the World Health Organization is largely based on the genotoxicity of acetaldehyde. Individuals with genetic polymorphisms in ALDH2, common in East Asian populations, accumulate higher levels of acetaldehyde and experience substantially elevated esophageal cancer risk when consuming alcohol (Brooks et al., 2009, PLoS Med).

This is not associative data. It is biochemical causation.

Mechanism 2: Oxidative Stress and Reactive Oxygen Species

Alcohol metabolism generates reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS cause lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial damage, and oxidative DNA injury. Chronic oxidative stress contributes to genomic instability, a core hallmark of cancer (Hanahan & Weinberg, 2011, Cell).

In hepatocytes, oxidative injury from alcohol contributes to cirrhosis, fibrosis, and eventually hepatocellular carcinoma (Rehm et al., 2010, Lancet). The pathway is cumulative. Years of exposure compound damage.

Mechanism 3: Hormonal Modulation, Especially in Breast Cancer

Alcohol increases circulating estrogen levels by altering hepatic metabolism and enhancing aromatase activity (Key et al., 2006, J Natl Cancer Inst). Elevated estrogen stimulates proliferation in hormone-sensitive tissues, including breast epithelium.

Even low levels of alcohol intake (as little as one drink daily) have been associated with measurable increases in breast cancer incidence (Bagnardi et al., 2015). In this context, alcohol acts not merely as a toxin but as a hormonal amplifier.

Mechanism 4: Impaired Immune Surveillance

Alcohol suppresses components of both innate and adaptive immunity. Chronic exposure reduces natural killer (NK) cell activity, impairs dendritic cell function, and disrupts T-cell signaling (Szabo & Saha, 2015, Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol).

Cancer development is not only about mutation. It is also about immune escape. If immune surveillance weakens, mutated cells are more likely to persist and expand. Alcohol shifts the balance.

Mechanism 5: Synergy With Other Carcinogens

Alcohol enhances mucosal permeability in the upper aerodigestive tract, allowing tobacco carcinogens to penetrate more deeply.

The combined effect of alcohol and tobacco is multiplicative, not additive, in cancers of the head, neck, and esophagus (Hashibe et al., 2009, Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev).

This synergy explains why dual exposure dramatically escalates risk.

The “Cardioprotective” Myth and Cancer Reality

For years, observational studies suggested moderate alcohol consumption might reduce cardiovascular mortality. More recent analyses have challenged that assumption, suggesting confounding variables may explain much of the apparent benefit (Griswold et al., 2018, Lancet).

Even if small cardiovascular benefits exist in certain populations, they must now be weighed against established cancer risk. In oncology, we do not accept “small carcinogenic exposure” as neutral.

Is There a Safe Level of Alcohol?

The World Health Organization has explicitly stated that there is no safe amount of alcohol when it comes to cancer risk (WHO, 2023 statement).

Risk increases linearly with dose, but it does not begin at heavy consumption. It begins at zero. This does not mean everyone who drinks will develop cancer. It means alcohol increases probability.

Cancer is a probabilistic disease driven by cumulative exposures.

Alcohol and Specific Cancer Types

Breast Cancer

Alcohol increases breast cancer risk by approximately 7–10% per additional daily drink (Bagnardi et al., 2015).

Colorectal Cancer

Chronic alcohol intake increases colorectal cancer risk, potentially via acetaldehyde exposure and microbiome alterations (Fedirko et al., 2011, Ann Oncol).

Liver Cancer

Alcoholic liver disease significantly increases hepatocellular carcinoma risk, particularly in combination with viral hepatitis (Rehm et al., 2010).

Esophageal Cancer

The ALDH2 deficiency interaction highlights the mechanistic causality between acetaldehyde accumulation and squamous cell carcinoma (Brooks et al., 2009).

Why This Conversation Is Still Uncomfortable

Alcohol is embedded in social identity. It is marketed aggressively. It is normalized in professional settings, including healthcare.

Unlike tobacco, alcohol does not carry the same public stigma. But the molecular evidence is clear. When discussing cancer prevention, clinicians routinely counsel smoking cessation, weight management, and HPV vaccination.

Alcohol deserves similar transparency.

The Oncology Perspective

Cancer prevention is often framed around genetics or environmental exposures beyond personal control. Alcohol is modifiable.

Reducing consumption decreases exposure to acetaldehyde, lowers oxidative stress, stabilizes hormonal levels, and improves immune function. The data are not controversial in scientific literature. They are controversial culturally.

Final Thought

Alcohol does not cause cancer in the simplistic, deterministic sense. But it increases risk through multiple converging pathways:

- Direct DNA damage

- Hormonal stimulation

- Oxidative injury

- Immune suppression

- Carcinogen synergy

The classification as a Group 1 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer is not based on speculation. It is based on decades of accumulated molecular, epidemiologic, and clinical evidence.

The real question is not whether alcohol raises cancer risk. It is whether we are ready to confront it with the same consistency and honesty we demand for other group 1 carcinogen.

Written by Armen Gevorgyan, MD