Nous-209 vaccine represents a novel cancer interception strategy designed to harness immune recognition of shared frameshift mutations arising from mismatch repair deficiency in Lynch syndrome. By targeting recurrent neoantigens that emerge early during tumorigenesis, this approach aims to activate protective antitumor immunity before invasive cancer develops, addressing a critical unmet need in hereditary cancer prevention.

Title: Nous-209 neoantigen vaccine for cancer prevention in Lynch syndrome carriers: a phase 1b/2 trial

Authors: Anna Morena D’Alise, Jason Willis, Fahriye Duzagac, Michael J. Hall, Marcia Cruz-Correa, Gregory E. Idos, Selvi Thirumurthi, Veroushka Ballester, Guido Leoni, Irene Garzia, Laura Antonucci, Lorenzo De Marco, Elisa Micarelli, Nan Deng, Laura Seclì, Sven Gogov, Wenli Dong, J. Jack Lee, Charles M. Bowen, Lana A. Vornik, Araceli Garcia-Gonzalez, Laura Reyes-Uribe, Ellen Richmond, Asad Umar, Powel H. Brown, Krishna M. Sinha, Luz Maria Rodriguez, Elisa Scarselli, Eduardo Vilar

Published in Nature, January 2026

Background

Lynch syndrome (LS) is a common hereditary cancer syndrome affecting ~1 in 300 individuals, driven by germline mismatch repair (MMR) gene mutations (MLH1, MSH2/EPCAM, MSH6, PMS2) and associated with substantial lifetime cancer risk—reported as 50–80% for colorectal cancer (CRC) and 40–60% for endometrial cancer, alongside elevated risk across multiple tumor types. Preventive options remain limited mainly to intensive surveillance, prophylactic surgery in selected settings, and aspirin chemoprevention (for example, 600 mg daily for 2 years in CAPP2, although high-dose use is often constrained by tolerability concerns).

Because MMR deficiency causes microsatellite instability (MSI) and recurrent frameshift insertions/deletions in coding microsatellites, many LS-associated precancers and cancers share frameshift peptide (FSP) neoantigens that are immunologically “non-self.” This creates a strong rationale for immune interception using an “off-the-shelf” multi-neoantigen vaccine capable of inducing broad, durable T-cell immunity before invasive cancer develops.

Methods

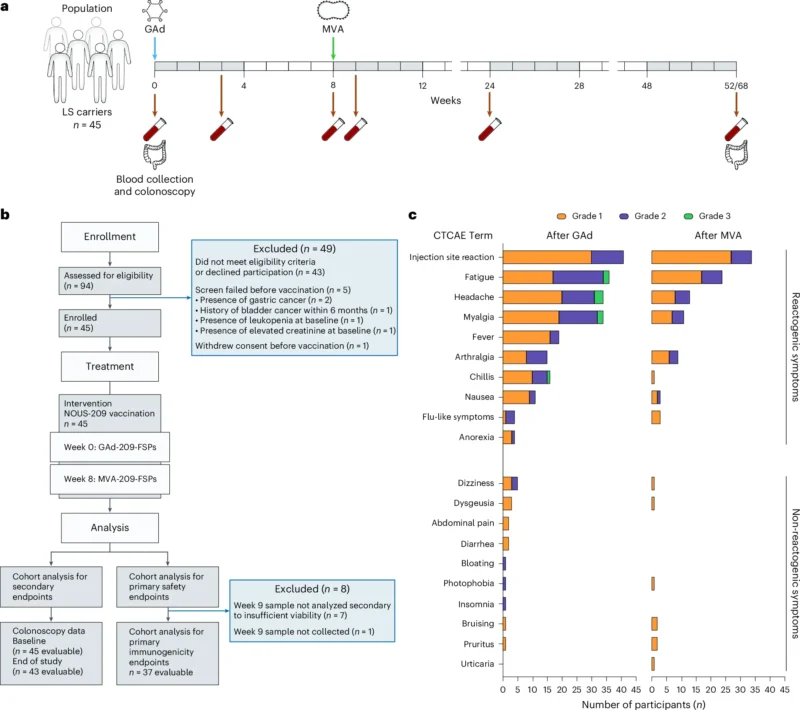

This report presents cohort 1 results from an open-label, multicenter phase 1b/2 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05078866) evaluating Nous-209 as cancer interception in LS carriers. Coprimary endpoints were safety (adverse events, including grade ≥3 toxicity) and immunogenicity assessed by ex vivo IFNγ ELISpot against vaccine-encoded FSPs. Prespecified secondary endpoints included endoscopic measures of colorectal neoplasia, including adenoma burden, advanced neoplasia, and carcinoma incidence.

Immunogenicity criteria required reactivity to at least one of 16 peptide pools (covering 209 FSPs), with specific rules for participants who had baseline reactivity (≥80% increase post-vaccination to count as vaccine-induced enhancement). Exploratory analyses assessed correlations between immune breadth and adenoma detection.

Study Design

Eligible participants were adults (≥18 years) with a documented LS mutation and no evidence of active or recurrent invasive cancer for at least 6 months before screening. Participants underwent standard-of-care baseline colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy; those found to have high-grade dysplasia or invasive carcinoma at baseline were excluded.

Nous-209 used a heterologous prime–boost viral-vector platform: an intramuscular priming dose of GAd20-209-FSPs at week 0 (day 1) followed by MVA-209-FSPs at week 8. Serial blood sampling occurred at baseline and at weeks 3, 8, 9, 24, and 52/68 for immune monitoring. The statistical framework included Simon’s minimax two-stage design for the immunogenicity endpoint: the trial targeted an acceptable response rate ≥75% and considered ≤55% unacceptable; the design planned 36 evaluable participants for immunogenicity, with up to 45 enrolled to meet evaluability goals.

Cohort 1 enrolled and vaccinated 45 LS carriers between November 2022 and November 2023 across four institutions within an NCI consortium (MD Anderson, University of Puerto Rico, Fox Chase, City of Hope). Most participants carried MSH2 mutations (47%), followed by MSH6 (24%), MLH1 (18%), and PMS2 (11%). Median age was 50 years (range 24–71); 56% were male; 91% self-reported White; and 42% (19/45) were cancer survivors without evidence of active malignancy within 6 months before enrollment.

Results

Safety and tolerability

Vaccination was well tolerated with no intervention-related serious adverse events (SAEs). During the first 9 weeks after vaccination, 98% (44/45) reported at least one adverse event, reflecting expected reactogenicity for viral-vectored vaccination.

Local injection-site reactions were common but mild:

- 91% experienced injection-site reactions after the GAd prime, and 76% after the MVA boost.

- No grade 3 injection-site reactions were observed.

Systemic symptoms were frequent but generally transient (reported duration 1–4 days, managed conservatively, sometimes with acetaminophen, without hospitalization):

- Fatigue: 80% after prime and 53% after boost; grade 3 fatigue occurred in 4% after prime or after boost.

- Myalgia: 76% after prime and 24% after boost; grade 3 myalgia occurred in 4% after prime or after boost.

Grade 3 symptoms were described as occurring after the prime dose and resolved fully; importantly, all participants received the booster dose as scheduled, supporting feasibility of the prime–boost schedule in a preventive population.

Immunogenicity: magnitude, breadth, and durability

Among evaluable participants for immunogenicity (n = 37), Nous-209 induced neoantigen-specific immune responses in 100% (37/37) at peak (week 9) by IFNγ ELISpot. The mean peak response was ~1,100 IFNγ spot-forming cells (SFCs) per 10⁶ PBMCs, indicating robust cellular immunity.

Durability remained a key signal for an interception strategy:

- At 6 months, responses remained detectable in 97% of evaluable participants.

- At 1 year, responses persisted in 85%.

As expected, immune responses contracted over time from peak, but remained measurable in the majority at one year.

Breadth was notable given the vaccine’s 209-FSP payload: participants recognized multiple peptide pools, with an average of 8 immunogenic pools per participant. Distribution of breadth showed heterogeneity but substantial multi-epitope coverage:

- 13% reacted to 1–3 pools

- 54% reacted to 4–9 pools

- 33% reacted to 10–16 pools

A small subset (10%, 4/37) had baseline spontaneous reactivity; vaccination either boosted these responses or induced additional de novo reactivity.

Using a strategy combining reactive pool identification with HLA class I binding predictions (EC50 <500 nM) when full deconvolution was not feasible, the investigators identified 115 immunogenic FSPs in the trial cohort. Importantly, in an independent dataset of LS MSI colorectal precancers and cancers, 94 of 115 (82%) immunogenic FSPs were present—supporting biological relevance of vaccine targets to early lesions and established tumors.

Both CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses were observed. Depletion experiments demonstrated that some responses were CD8-mediated (reduced IFNγ after CD8 depletion), while others were CD4-mediated (no substantial change), indicating coordinated cellular immunity rather than a narrow single-subset effect.

Functional cytotoxic potential was supported in multiple ways. For a recurrent immunogenic FSP (SPEF2-derived), dextramer staining identified antigen-specific CD8+ T cells detectable ex vivo after vaccination, persisting to 6 months and 1 year, with a phenotype consistent with differentiated effector memory (TemRA). CD8+ T cells also expressed cytotoxic degranulation markers (CD107a) and produced IFNγ on antigen stimulation. Additionally, a microfluidic 3D co-culture killing assay using genetically modified HCT116 cells expressing a CDC7 frameshift antigen demonstrated significantly reduced tumor cell survival and increased caspase 3/7 apoptosis with post-vaccination PBMCs compared with baseline and controls (P < 0.0001 in reported comparisons), aligning immune readouts with antigen-specific tumor cell killing in vitro.

End-of-study colonoscopy signals (secondary endpoint)

Among 43/45 participants evaluable for end-of-study colonoscopy (two withdrew before the procedure), 31 had no adenomas detected. A total of 23 adenomas were detected in 12 participants, and none were advanced adenomas (no >10 mm, no high-grade dysplasia, no villous histology). Notably, two participants had advanced adenomas at baseline, whereas none did at end of study. There was no colorectal cancer detected on end-of-study colonoscopy. The study was not powered for clinical prevention endpoints, and overall adenoma proportions did not show statistically significant differences versus baseline, but the absence of advanced adenomas post-vaccination was described as an encouraging early signal warranting larger randomized evaluation.

Exploratory analysis linked immune breadth to adenoma findings: at 6 months, participants without adenomas showed greater breadth of response (mean ~4 pools) than those with adenomas (mean ~1.5 pools; P = 0.0381). This association was not clearly maintained at 12 months, consistent with expected immune contraction and limited power.

Three participants were diagnosed with invasive noncolorectal cancers during follow-up (including one MMRd gastric cancer, one MMR-unknown NSCLC, and one MMR-proficient prostate cancer), highlighting that LS interception strategies likely need to address multi-organ risk and longer follow-up.

Key Findings

Nous-209 demonstrated a favorable safety profile in healthy LS carriers, with no treatment-related SAEs and mostly transient reactogenicity. Immunogenicity was universal among evaluable participants (100%), with strong peak IFNγ ELISpot responses (~1,100 SFC/10⁶ PBMCs) and durable detectability at one year (85%). Responses were broad, often spanning multiple peptide pools, and included both CD8+ and CD4+ components with in vitro evidence of cytotoxic tumor-cell killing.

Vaccine-targeted FSPs overlapped substantially with neoantigens found in independent LS MSI precancers and cancers, supporting mechanistic plausibility for interception. End-of-study colonoscopy showed no CRC and no advanced adenomas among evaluable participants, with exploratory data suggesting greater immune breadth may associate with lower adenoma detection.

Conclusion

In this phase 1b/2 single-arm cohort of 45 Lynch syndrome carriers, Nous-209 achieved its coprimary goals: it was safe without treatment-related serious adverse events and elicited robust, broad neoantigen-specific T-cell immunity in all evaluable participants, with durable responses persisting in most through one year. The immunologic breadth aligns with the biological challenge of heterogeneous, future MSI-driven lesions in LS, and the overlap between immunogenic FSPs and those detected in independent LS precancer and cancer datasets strengthens the interception rationale. Secondary endoscopic findings—particularly the absence of advanced adenomas and colorectal cancer at end-of-study colonoscopy—are hypothesis-generating rather than definitive, given the nonrandomized design, modest sample size, limited demographic diversity, and short timeframe for cancer prevention outcomes.

Together, these data support continued clinical development of Nous-209 for cancer interception in Lynch syndrome, with future larger, randomized studies needed to determine whether immune responses translate into reduced MSI lesion progression and lower long-term cancer incidence, and whether annual boosting meaningfully enhances protection.