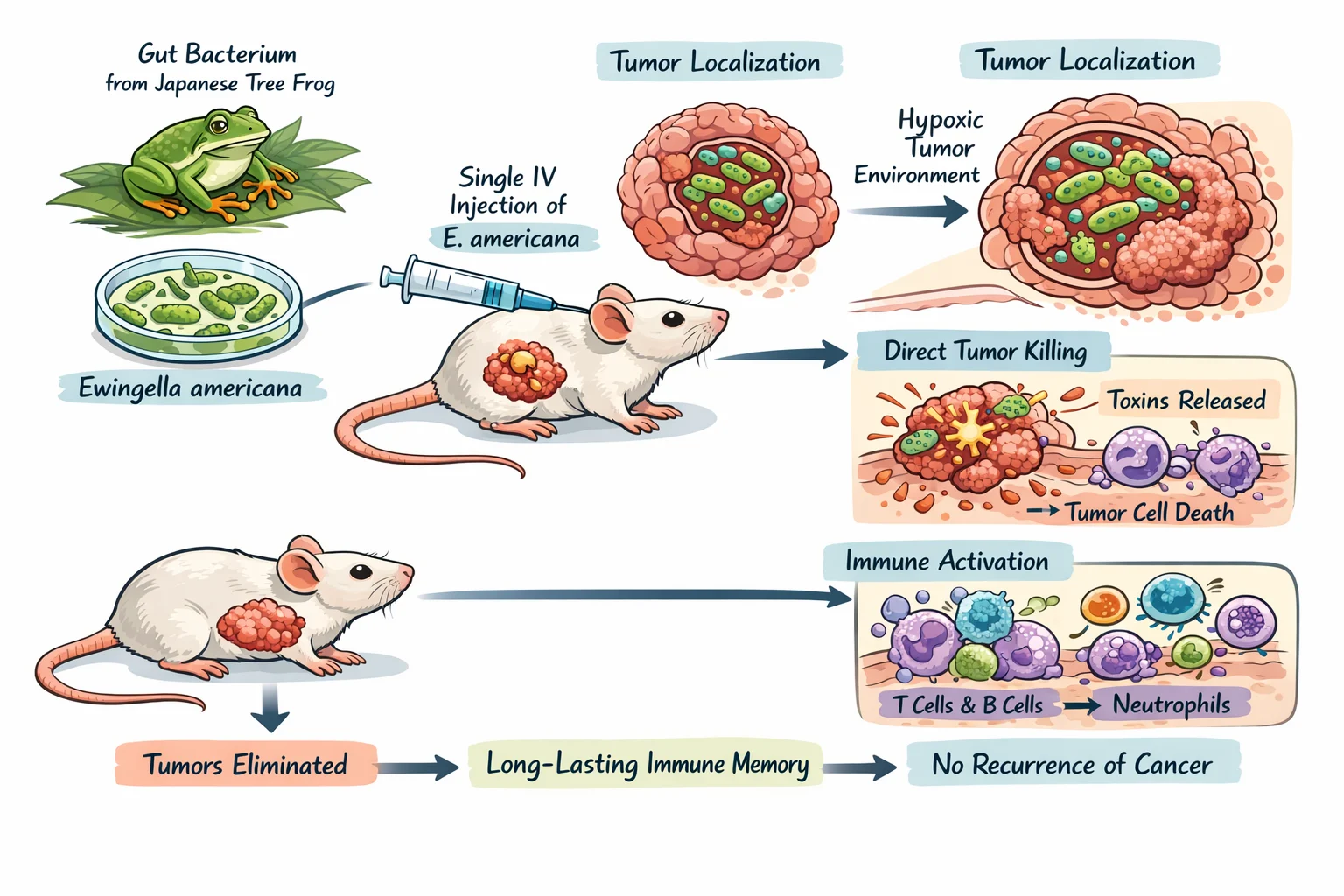

A research group at the Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology has reported that a gut bacterium isolated from the Japanese tree frog can eliminate colorectal tumors in mice after a single intravenous administration. The work centers on a strain of Ewingella americana and proposes a dual mechanism that combines direct tumor cell killing with strong activation of the host immune response.

The investigators’ broader rationale was ecological and biological: spontaneous tumors are considered uncommon in many amphibians and reptiles, despite life histories that include major physiological stressors and frequent microbial exposure. This prompted the hypothesis that gut microbes, in addition to host biology, might contribute to anticancer protection and could contain therapeutically relevant strains.

From Biodiversity Screening To a Lead Candidate

The team isolated and cultured forty-five bacterial strains from three animal sources: Japanese tree frogs (Dryophytes japonicus), Japanese fire-belly newts (Cynops pyrrhogaster), and Japanese grass lizards (Takydromus tachydromoides). Systematic screening identified nine strains with antitumor activity, with the strongest effects attributed to the tree frog–derived E. americana.

The approach differs from many microbiome-oncology strategies that focus on indirect modulation of the intestinal community. Instead, the study evaluated isolated, individually cultured strains as direct agents administered to target tumors.

Antitumor Activity in Mice and Comparison With Standard Treatments

In a mouse colorectal cancer model, a single intravenous dose of E. americana achieved complete tumor elimination across the treated animals, reported as a complete response rate of one hundred percent. In the same experimental framework, the bacterium’s tumor regression performance exceeded comparator arms that included an immune checkpoint inhibitor targeting PD-L one and liposomal doxorubicin.

Beyond initial regression, a separate observation described in secondary reporting noted that mice re-challenged with cancer cells did not form new tumors, suggesting the possibility of durable immune memory. This aspect will require confirmation and expansion in future controlled studies, but it is consistent with an immunologically engaged mechanism.

Proposed Mechanism: Tumor Localization Plus Immune Activation

The investigators describe E. americana as a facultative anaerobe with a preference for the hypoxic conditions typical of solid tumor microenvironments. After administration, bacterial counts within tumors were reported to rise by roughly three thousand-fold within about one day, alongside selective accumulation in tumor tissue and an absence of colonization in major healthy organs.

Mechanistically, the study outlines two complementary actions. First, the bacterium can directly damage tumor cells after localizing to the tumor microenvironment. Second, bacterial presence is associated with pronounced immune recruitment and activation, including increased infiltration of T cells, B cells, and neutrophils and elevations in inflammatory cytokine signaling such as tumor necrosis factor alpha and interferon gamma, which can amplify antitumor immune activity.

Safety Signals Reported in The Murine Model

Safety assessments in mice indicated rapid clearance from the bloodstream, with a reported half-life on the order of roughly one hour and no detectable circulating bacteria by about one day after dosing. The inflammatory response was described as transient, resolving within several days, and extended observation over approximately two months did not identify chronic toxicity in treated animals.

These findings, while encouraging, remain preclinical. Murine safety does not guarantee human safety, and intravenously administered live bacterial therapeutics require particularly rigorous manufacturing controls, dosing studies, and clinical monitoring before any patient use.

What This Could Mean for Bacterial Therapeutics in Oncology

Live bacteria and bacteria-derived platforms have long been explored for tumor targeting because solid tumors can present niches—such as hypoxia, abnormal vasculature, and local immune suppression, that are less hospitable in healthy tissues. The JAIST study adds to this area by proposing a naturally occurring strain with tumor-selective behavior and combined cytotoxic and immunomodulatory activity, without genetic engineering in the reported experiments.

The authors also frame the results as a broader argument for therapeutic discovery from under-characterized microbiomes, particularly in lower vertebrates, where microbial diversity remains incompletely mapped.

Key Limitations and Next Steps

The evidence so far comes from mouse models of colorectal cancer, and translation to humans is uncertain. Differences in tumor biology, immune responses, microbiological susceptibility, and tolerability can all change efficacy and risk profiles. Dose optimization, delivery strategy refinement, and reproducibility across models and tumor types will be essential.

According to the researchers’ stated development pathway, next steps include evaluating efficacy in additional solid tumors such as breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and melanoma; refining administration strategies; and assessing potential combination approaches alongside existing immunotherapies or chemotherapies.

Publication Details

The study is published in Gut Microbes under the title “Discovery and characterization of antitumor gut microbiota from amphibians and reptiles: Ewingella americana as a novel therapeutic agent with dual cytotoxic and immunomodulatory properties,” with the DOI ten point one zero eight zero slash one nine four nine zero nine seven six dot two zero two five dot two five nine nine five six two.

More posts about oncology news on OncoDaily.

Written by Nare Hovhannisyan, MD