Parth Sharma, Blog editor at the Association for Socially Applicable Research (ASAR), and Vid Karmarkar, Founder and CEO of Canseva Foundation, shared an atricle in thinkglobalhealth.org about Financial toxicity of cancer in India:

“After Rajesh was diagnosed with oral cancer, his son Mohan dropped out of his bachelor’s degree program to run his father’s pickle stall, the family’s only source of income. Not long after, Mohan was forced to close the stall to move to Delhi for his father’s treatment.

“We spent all our savings in our village at the local doctor, who assured us of a cure,” said Mohan as he waited for his father to complete his daily dose of radiation therapy in a government hospital in the city. “We have a debt of two lakh rupees [$2,400] now. Today, I had to borrow money to even come to the hospital,” he added.

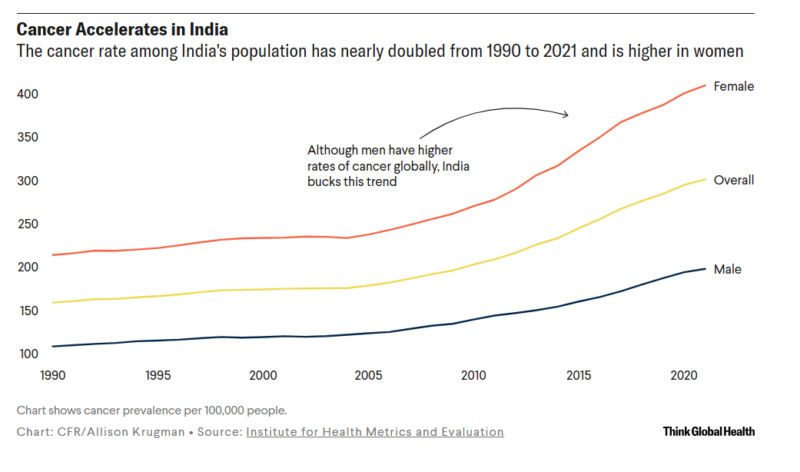

One in every nine people in India are expected to be diagnosed with cancer during their lifetime. With 1.4 million people diagnosed with cancer in 2022, India has the third-highest burden of cancer globally—in terms of cases—after the United States and China. Given rising pollution, urbanization, and worsening diets and lifestyles, India’s cancer burden is expected to rise further, but public-funded cancer treatment centers are scarce, leading to financial toxicity in families dealing with a cancer diagnosis.

Financial toxicity refers to the hardships patients and their families face due to the high cost of medical care. Doctors actively look out for the physical toxicities of cancer treatment, including nausea, vomiting, and infections, but the financial toxicity of the disease often goes unnoticed.

Reasons for Financial Toxicity of Cancer

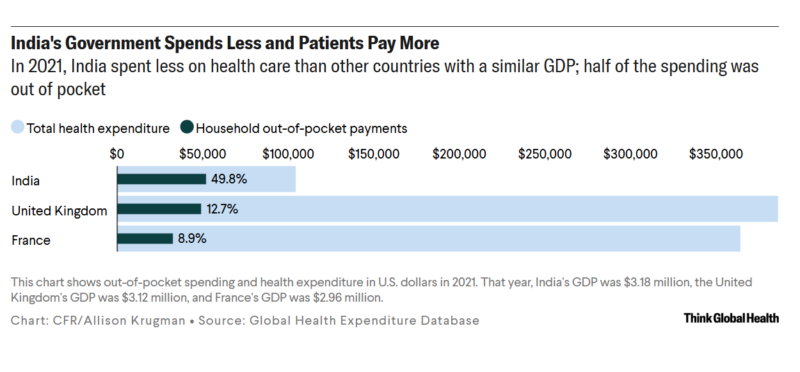

With government health expenditure hovering around 1.5% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP), health care is primarily financed by out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE)—that is, people spending their own money on health care.

When money is spent on seeking health care, it is known as direct OOPE. Direct OOPE can be either medical expenses themselves—doctor’s consultation fees, drugs, and procedures—or nonmedical expenses such as the cost of travel, accommodation, and food for people relocating to larger cities for treatment. Indirect OOPE is when the source of income is disrupted or productive hours are lost due to absence from work for treatment.

Nearly 70% of India’s population is still rural, but cancer treatment options are concentrated in a few cities. This situation forces people to relocate to cities, increasing both direct nonmedical and indirect OOPE for cancer care. In cities, the overcrowded and underfunded public health-care system pushes people to seek care in private clinics. These clinics offer the advantage of early diagnosis and treatment, but the high cost of treatment financially destroys families, pushing them into generational poverty.

Ideally, seeking care in publicly funded hospitals should be free and should not result in high direct OOPE. However, government hospitals are underfunded, poorly equipped, and have long waiting times, pushing patients to seek care in private clinics. “The blood collection time is 9:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. and it takes one week to get the report. We therefore advise patients to get tests done outside to avoid delays in treatment,” said a health-care worker from a leading tertiary public health center in north India. In government hospitals, the waiting period is often more than three months for CT scans and two years for MRI scans.

Poorly stocked pharmacies in government hospitals also add to patients’ woes. “I had 500 [$6] rupees to come here. I spent 200 rupees to travel to the hospital. I was asked to buy a medicine that was not available in the pharmacy here, so I had to spend 200 more to purchase it from the shop outside the hospital. Now I have only 100 rupees left. How will I go back home now?” asked Ms. Afreen, who was traveling from a village nearly 50 kilometers (31 miles) away to accompany her sister for treatment.

Often the patient’s family members are forced to stop education midway for various reasons, such as limited financial resources, the need for a caregiver, or the need for an extra earning member in the family. The impact of the cancer on the family is even worse when the breadwinner is affected by the disease. “Previously we used to buy a lot of fruits, but we have stopped now. On most days, affording three meals is also a challenge,” said Ravi, whose father is suffering from oral cancer. The lack of education and deterioration of nutrition thus harm not only the family but also successive generations into a multilayered poverty of finances, education, and nutrition.

Given limited insurance coverage, many are forced into distress financing—borrowing money, pawning jewelry, depleting savings, or selling assets. The high interest rates that informal money lenders charge often create debt traps for families and the following generations.

Initiatives to Address Financial Toxicity

Addressing the financial strain of cancer is crucial because it leads to delays in seeking care, lack of follow-up, or treatment abandonment, thus affecting treatment outcomes. Recognizing this, the Indian government has taken several steps to reduce the financial burden on patients and their families.

In 2018, India launched Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB PM-JAY) to move toward universal health coverage. The program offers 500,000 rupees (about $6,000) per family annually for hospital care. Additionally, various states have introduced their own financial support programs. For example, to reduce the burden on the public health system, the Delhi Arogya Kosh scheme in the national capital provides financial assistance for various investigations in impaneled private centers for residents of Delhi. States such as Maharashtra, Punjab, and Kerala have followed suit with similar initiatives to financially support cancer care.

To alleviate nonmedical costs, Indian Railways and Air India offer discounted fares for patients and caregivers, and Himachal Pradesh and Haryana provide free bus travel for patients with cancer. Monthly pension schemes in states such as Haryana, Tripura, and Himachal Pradesh further help offset the indirect cost of cancer.

Some efforts to reduce the financial toxicity of cancer have also been taken in the nongovernmental sector. The National Cancer Grid, a network of major cancer centers, research institutes, patient groups, and charitable institutions across India, reduced the cost of cancer drugs by 82% through pooled procurement of 40 anticancer high-value drugs.

Cachar Cancer Hospital and Research Center in Assam, in northeastern India, has taken a comprehensive approach by helping mitigate direct and indirect OOPE by providing highly subsidized cancer treatment as well as lodging, food, and ad hoc jobs for caregivers traveling with patients from different parts of the region for treatment at the center. Similarly, in south India, Pallium India, India’s leading palliative care organization, provides both vocational rehabilitation to people living with cancer as well as free home-based palliative care to alleviate their suffering and ensure they have a dignified life.

The Way Forward

Given limited government spending on health care, the private sector has seized the opportunity to fill the void with “band-aid” solutions, but this has come at a price making health care a luxury good in India. To achieve truly universal health care and sustainably alleviate financial toxicity in cancer treatment, there is no substitute for increasing the related government budget.

Improving public health infrastructure in the country to promote early diagnosis and appropriate treatment for cancer is sorely needed. Although government-funded health insurance schemes lessen some financial burdens on patients, they only partially address the problem by covering only in-patient care. The patients still have to bear the cost of out-patient care, including consultation fees of doctors, and the cost of investigations and drugs.

Improving the social security of patients and their families is also needed. Pension schemes and food security schemes need to be extended to include patients (and their families) living with life-limiting illnesses such as cancer. To protect future generations from poverty, the government should ensure that the children in such vulnerable families receive their right to education.

India urgently needs to focus on protecting its people not just from the rising cancer burden but also from collateral damage.”

Vid Karmarkar is the Founder and CEO of the Canseva Foundation. With a background in strategy consulting and launching ventures in healthcare, genomics, and oncology, he brings a techno-commercial perspective to cancer care. Previously, he worked as an International Business and Market Access Consultant for Precision Oncology at Datar Cancer Genetics Limited, collaborating with oncologists across India.

Parth Sharma is a physician and researcher, currently serving as a Research Fellow with the Reimagining India’s Health System: A Lancet Citizens’ Commission. He is also the blog editor for the Association for Socially Applicable Research (ASAR) in Pune, India, and a commission fellow at The Lancet Citizens’ Commission for Reimagining India’s Health System. Additionally, he is the founder and editor of Nivarana.