What is pheochromocytoma?

Pheochromocytoma is a rare neuroendocrine tumor that originates from chromaffin cells in the adrenal medulla, which are responsible for producing catecholamines such as epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline). These hormones are crucial for the body’s “fight or flight” response, regulating heart rate, blood pressure, and other vital functions. Pheochromocytomas can also occur outside the adrenal glands, in which case they are referred to as paragangliomas. These tumors can cause a variety of symptoms due to the excessive secretion of catecholamines, leading to significant clinical challenges

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Pheochromocytoma is a rare condition, with an estimated incidence of 0.66 cases per 100,000 people per year. The prevalence of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma has been reported to be around 64.4 per million inhabitants. The incidence of these tumors has increased over time, likely due to improved diagnostic techniques and increased use of imaging studies, which often detect these tumors incidentally.

These tumors can occur at any age but are most commonly diagnosed in individuals between 30 and 50 years old. They affect both men and women equally, although some studies suggest a slight female predilection with a female-to-male ratio of 1.4:1. The tumors are often part of hereditary syndromes, with about 25-35% of cases being linked to genetic mutations. These genetic syndromes include multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2), von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome, and neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause of pheochromocytoma is not fully understood, but research has identified several risk factors and potential contributing factors:

Genetic Factors

Approximately 30-40% of pheochromocytomas are associated with inherited genetic syndromes. These include:

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2): Caused by mutations in the RET proto-oncogene (a gene involved in cell signaling, and its mutations can cause cancers), this syndrome increases the risk of developing pheochromocytoma, medullary thyroid cancer, and other endocrine tumors.

- Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease: Caused by mutations in the VHL gene (regulates cell growth), this syndrome is associated with an increased risk of pheochromocytoma, as well as other tumors like renal cell carcinoma and hemangioblastomas.

- Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1): Also known as von Recklinghausen’s disease, this genetic disorder caused by mutations in the NF1 gene (produces neurofibromin, a protein that helps regulate cell growth) can increase the risk of pheochromocytoma.

- Familial paraganglioma syndromes: These are rare inherited conditions caused by mutations in genes like SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD, which can lead to the development of paragangliomas, a type of tumor related to pheochromocytoma.

If you have a family history of any of these genetic syndromes, it is important to discuss genetic testing with your healthcare provider to assess your risk and develop an appropriate screening and management plan.

Other Risk Factors

In addition to genetic factors, other potential risk factors for pheochromocytoma include:

- Age: Pheochromocytomas can occur at any age, but they are most commonly diagnosed in people between 30 and 50 years old.

- Obesity: Some studies have suggested a link between obesity and an increased risk of pheochromocytoma, though the exact mechanisms are not fully understood.

- Exposure to certain chemicals or radiation: There is some evidence that exposure to certain chemicals, such as pesticides, or radiation may increase the risk of developing pheochromocytoma, but more research is needed in this area.

Prognosis

The prognosis for individuals with pheochromocytoma is generally good, especially when the tumor is detected and treated early.

However, the prognosis can vary depending on several factors, including:

- Tumor size and location: Larger tumors and those that have metastasized (spread to other parts of the body) are associated with a poorer prognosis.

- Genetic factors: Individuals with certain genetic syndromes, such as MEN2 and VHL, may have a higher risk of developing more aggressive or recurrent pheochromocytoma.

- Presence of complications: If pheochromocytoma is left untreated, it can lead to serious, life-threatening complications, such as heart failure, stroke, or organ damage, which can significantly impact prognosis.

Long-term follow-up studies indicate that the risk of recurrence is significant, even for tumors that appear benign at diagnosis. Patients with hereditary tumors have a higher risk of recurrence compared to those with sporadic tumors. Therefore, lifelong follow-up is recommended for all patients diagnosed with pheochromocytoma.

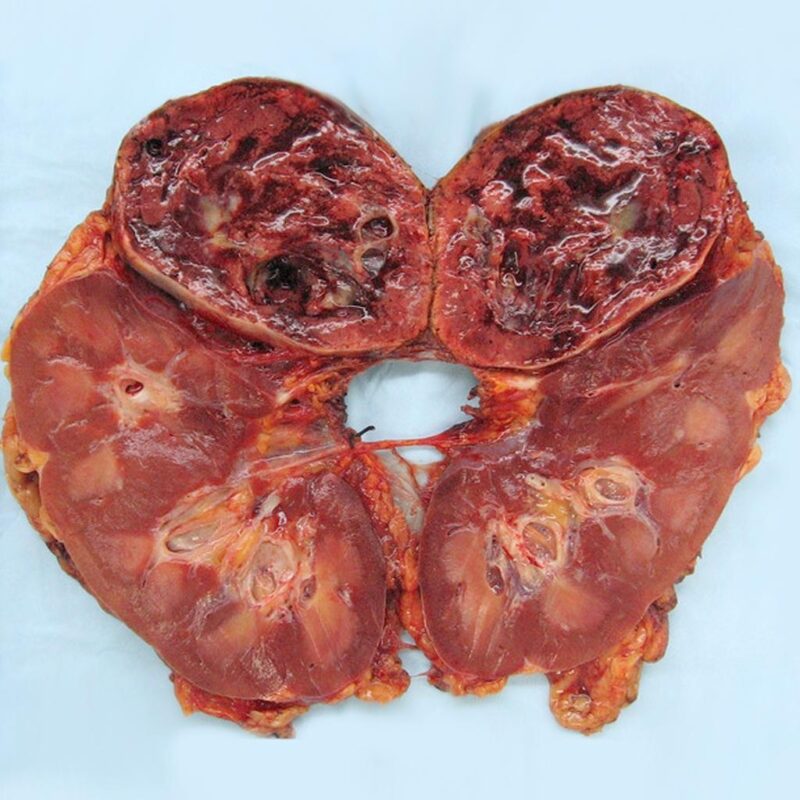

Gross pathology of pheochromocytoma. The image is taken from radiopaedia.org.

Staging

There is no universally accepted staging system for pheochromocytoma, as these tumors are relatively rare and their behavior can be unpredictable. However, some general principles regarding the staging and classification of pheochromocytomas include:

- Localized pheochromocytoma: Tumors that are confined to the adrenal gland or a single paraganglionic site.

- Metastatic pheochromocytoma: Tumors that have spread to other parts of the body, such as the liver, bones, or lymph nodes.

- Functional vs. non-functional: Pheochromocytomas can be classified based on whether they actively secrete catecholamines (functional) or not (non-functional).

- Hereditary vs. sporadic: As mentioned earlier, approximately 30-40% of pheochromocytomas are associated with inherited genetic syndromes, while the remaining cases are considered sporadic.

While there is no universally accepted staging system, some healthcare providers may use a modified version of the TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) staging system to describe the extent of the disease. This can help guide treatment decisions and provide a general indication of prognosis.

Symptoms

Pheochromocytoma can present with a wide range of symptoms, often making it difficult to diagnose. The symptoms are primarily due to the excessive production of catecholamines and can include:

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- Rapid or forceful heartbeat (palpitations)

- Severe headaches

- Profound sweating

- Tremors

- Anxiety or panic attacks

- Nausea and vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Weight loss

- Visual disturbances

- Flushing of the face

- Pale skin tone

- Dizziness

- Constipation

These symptoms can occur in sudden, intense spells that last from a few minutes to an hour. Triggers for these spells can include physical exertion, stress, changes in body position, and certain foods or medications.

In this video, produced by Carling Adrenal Center, Sara shares her experience with pheochromocytoma.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing pheochromocytoma involves a combination of biochemical tests and imaging studies. The primary biochemical tests include measuring plasma free metanephrines or urinary metanephrines, which are metabolites of catecholamines. Plasma-free metanephrines have a sensitivity of up to 99% and are considered the most reliable initial test.

Imaging studies are used to localize the tumor once biochemical tests confirm the diagnosis. Common imaging modalities include:

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Provides detailed images of the adrenal glands and surrounding tissues.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Preferred for children and pregnant women due to the absence of ionizing radiation.

- Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) Scintigraphy: Uses a radioactive compound that is taken up by pheochromocytoma cells, helping to identify the tumor location.

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Scan: Emerging as a promising technique for detecting and localizing pheochromocytomas.

Genetic testing is also recommended, especially for patients with a family history of pheochromocytoma or related genetic disorders such as MEN2, VHL syndrome, and NF1.

Treatment

The primary treatment for pheochromocytoma is surgical removal of the tumor. The specific treatment approach depends on the stage of the tumor:

Localized Pheochromocytoma

For localized tumors, surgery is the mainstay of treatment. The entire adrenal gland may be removed if the tumor is located within it. Preoperative medical preparation is critical to control blood pressure and prevent complications during surgery. This typically involves the use of drugs that block the action of catecholamines.

Regional Pheochromocytoma

When the tumor has spread to nearby organs or lymph nodes, surgery is still the primary treatment. The affected organs or lymph nodes may also be removed during the procedure. Preoperative medical management remains essential to control hormone levels and blood pressure.

Metastatic Pheochromocytoma

For metastatic pheochromocytoma, treatment options are more complex and may include a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and targeted therapies. Clinical trials may also be an option for patients with metastatic disease. Palliative care is important to manage symptoms and improve the quality of life.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is often used for metastatic pheochromocytoma. The most common regimen includes cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine (CVD). This combination has shown to decrease tumor size and facilitate blood pressure control in about 33% of patients with metastatic pheochromocytoma-sympathetic paraganglioma. Other chemotherapeutic agents and combinations are also being explored in clinical trials.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy, including external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), is used to treat metastatic or unresectable pheochromocytomas. EBRT has shown to provide symptomatic control and local tumor control in a significant number of patients. SBRT is preferred for smaller tumors and can deliver high doses of radiation with minimal damage to surrounding tissues.

Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapies, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors, are being investigated for their efficacy in treating metastatic pheochromocytoma. These therapies target specific molecular pathways involved in tumor growth and have shown promise in clinical trials.

Patient’s Survivorship

Survivorship for patients with pheochromocytoma involves long-term follow-up to monitor for recurrence and manage any ongoing symptoms. Regular follow-up visits typically include biochemical testing for catecholamines and their metabolites, as well as imaging studies to detect any new tumor growth.

Patients with hereditary pheochromocytoma require more intensive follow-up due to the higher risk of recurrence. Genetic counseling and testing are recommended for patients and their family members to identify those at risk and implement appropriate surveillance strategies.

Follow-Up Care

- Biochemical Testing: Annual blood and urine tests to check for elevated levels of catecholamines and their metabolites, such as metanephrines and normetanephrines, are essential. Elevated levels can indicate tumor recurrence.

- Imaging Studies: Regular imaging studies, including CT scans, MRI, and MIBG scintigraphy, are recommended to detect any new tumor growth. These should be done annually, especially for patients with a high risk of recurrence.

- Genetic Testing: For patients with hereditary pheochromocytoma, genetic counseling and testing are crucial. This helps in identifying at-risk family members and implementing appropriate surveillance strategies.

- Physical Examinations: Regular physical exams to monitor blood pressure and overall health are important. Hypertension is a common issue both before and after treatment, and ongoing management is necessary

Problems During and After Treatment and How to Manage Them

Hypertension

Hypertension is a common issue both before and after treatment. Preoperative management with alpha-blockers and beta-blockers (blocks the action of catecholamines) is essential to control blood pressure. Postoperatively, patients may continue to require antihypertensive medications until catecholamine levels normalize.

Surgical Complications

Surgical complications can include bleeding, infection, and damage to surrounding organs. Careful preoperative planning and intraoperative monitoring are crucial to minimize these risks. Postoperative care involves monitoring for signs of complications and managing pain and other symptoms.

Recurrence

The risk of recurrence necessitates lifelong follow-up. Regular biochemical testing and imaging studies are essential to detect any new tumor growth early. Patients should be educated about the signs and symptoms of recurrence and advised to seek medical attention if they experience any concerning symptoms.

Hormone Replacement

If both adrenal glands are removed, patients will require lifelong hormone replacement therapy to manage adrenal insufficiency. This involves taking medications to replace the hormones normally produced by the adrenal glands, such as cortisol and aldosterone.

Psychological Support

A diagnosis of pheochromocytoma can be stressful and anxiety-inducing for patients and their families. Psychological support, including counseling and support groups, can help patients cope with the emotional impact of the disease and its treatment.

Hypoglycemia

A relatively rare risk after surgical resection is hypoglycemia due to excessive rebound secretion of insulin. This can occur as the tumor’s suppressive effects on insulin are removed. Close monitoring of blood glucose levels and appropriate management are necessary.

Postoperative Hypotension

After tumor removal, there can be an abrupt decline in catecholamine levels, leading to postoperative hypotension. Careful monitoring and management with intravenous fluids and/or vasopressors may be required.

Pheochromocytoma Crisis

Some patients may present with a pheochromocytoma multisystem crisis, a life-threatening condition involving cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurological, gastrointestinal, renal, hepatic, and metabolic systems. This can occur spontaneously or be triggered by tumor manipulation, trauma, corticosteroids, beta-blockers, anesthetic drugs, or non-adrenal surgical stress. These patients should be treated as medical emergencies.

Conclusion

Pheochromocytoma is a rare but treatable condition that requires careful management and lifelong follow-up. Early detection and appropriate treatment, primarily through surgical resection, can significantly improve patient outcomes. A multidisciplinary approach involving endocrinologists, surgeons, anesthetists, and other specialists is crucial for managing the perioperative and postoperative phases effectively.

Patients should be aware of the potential for recurrence and the importance of regular follow-up visits, which include biochemical testing and imaging studies. Managing complications such as hypertension, surgical risks, and the need for hormone replacement therapy is essential for long-term health.

Despite the challenges, advancements in medical and surgical treatments offer hope for improved outcomes. With comprehensive care and support, patients can lead fulfilling lives. Staying informed and proactive in their care empowers patients to manage their condition effectively and look forward to a brighter future.

Sources

- Pheochromocytoma – American Society of Clinical Oncology

- Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma Treatment – National Cancer Institute

- Management of Patients with Treatment of Pheochromocytoma: A Critical Appraisal – Cancers

- Treatments for cancerous pheochromocytoma – Canadian Cancer Society

- Pheochromocytoma – Pheopara Alliance

- Adrenal Cancer – American Cancer Society