NGS (Next Generation Sequencing) in Sarcoma Diagnostics was the focus of a plenary session lecture delivered by Dr. David J. Papke of Harvard Medical School at the 7th CUHK Sarcoma Masterclass in Hong Kong. During this session, Dr. Papke emphasized how integrating sequencing with next-generation immunohistochemistry can enhance diagnostic accuracy, identify therapeutic targets, and support personalized treatment strategies for sarcoma patients.

Background

Accurate diagnosis is the cornerstone of effective sarcoma management. Sarcomas are a heterogeneous group of rare tumors that require precise pathological classification to guide therapy. Traditionally, histopathology has been the gold standard for diagnosis, providing morphological insights into tumor subtypes. However, advances in molecular oncology have revealed that morphology alone is often insufficient to capture the genetic complexity of sarcomas.

In recent years, Next Generation Sequencing (NGS)has emerged as a powerful tool to identify genetic alterations, stratify subtypes, and uncover therapeutic targets. NGS enables broad profiling of multiple genes in parallel, providing information that can influence treatment decisions, especially in an era of precision oncology. Despite its utility, NGS is costly, labor-intensive, and time-consuming, making it impractical to apply universally across all sarcoma cases. This challenge has led to growing interest in next-generation immunohistochemistry (IHC) approaches, which may serve as cost-effective surrogates for specific genetic alterations and reduce the need for routine sequencing.

The Importance of Accurate Diagnosis

The foundation of sarcoma management is an accurate diagnosis. If the diagnosis is wrong, every subsequent treatment decision risks being ineffective or even harmful. Multiple studies from major sarcoma centers have shown that when pathology slides are reviewed by sarcoma subspecialists, discrepancies with the original diagnosis occur in up to thirty percent of cases.

Importantly, around ten percent of these discrepancies are considered major, directly altering clinical management. This reflects both the complexity of sarcoma classification and the challenges faced by general pathologists in interpreting rare tumors.

When Morphology and Immunohistochemistry Are Enough?

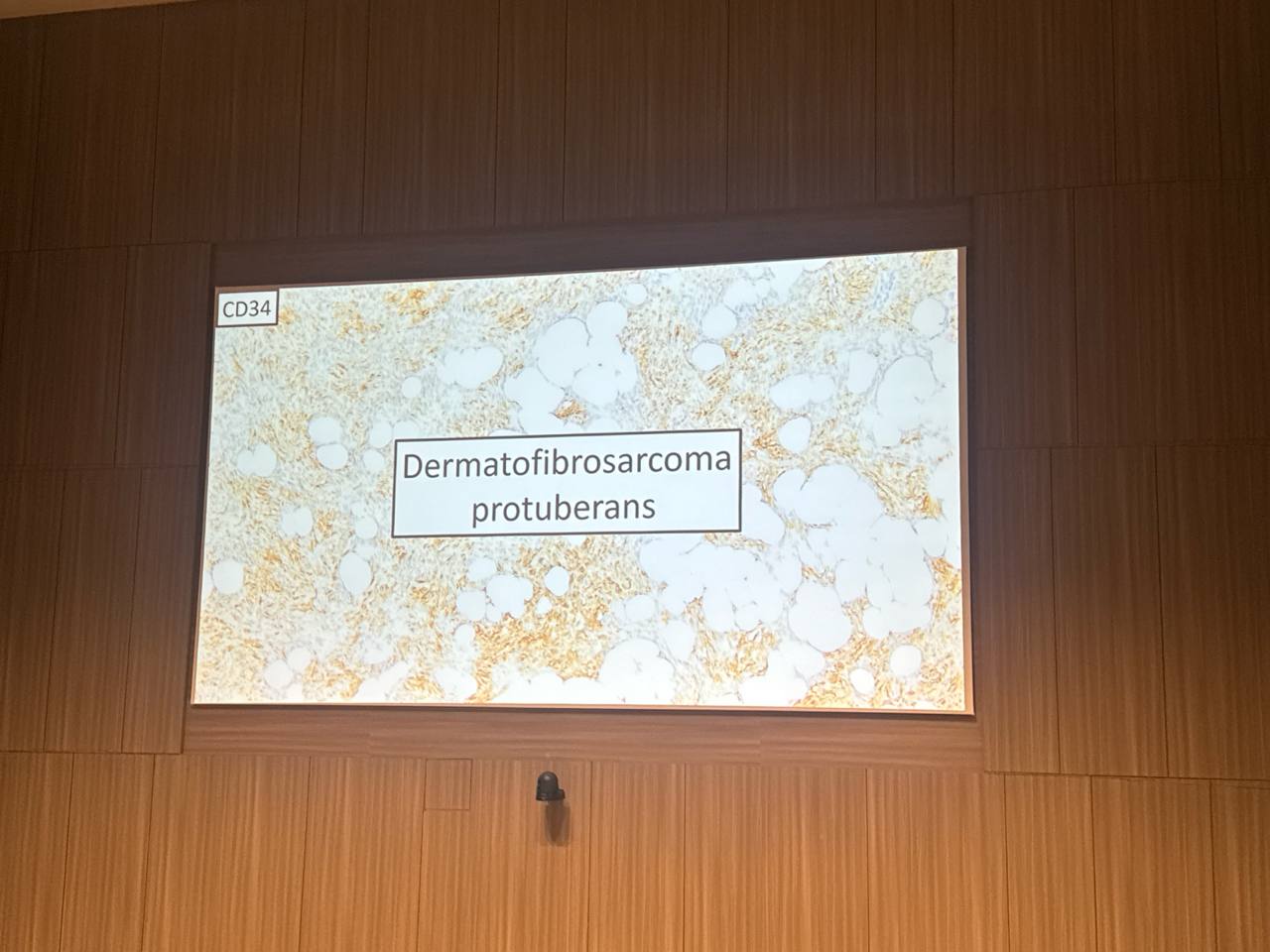

Many sarcomas can be confidently diagnosed on the basis of morphology, sometimes with the support of basic immunohistochemistry. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, for instance, demonstrates a storiform growth pattern and CD34 positivity, while myxofibrosarcoma is recognized by its myxoid lobules and infiltrative margins. Pleomorphic sarcomas, including pleomorphic liposarcoma, pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, are typically diagnosed by their histologic features alone. In these situations, sequencing adds little or no value, and if molecular results are not expected to influence management, testing should not be performed.

Immunohistochemistry has itself advanced dramatically. Traditional markers such as Desmin, Myogenin, and CD31 remain essential for lineage determination, but modern practice increasingly relies on next-generation immunohistochemistry. These stains act as surrogates for specific genetic events, allowing pathologists to confirm diagnoses without molecular assays. Examples include SS18::SSX detection in synovial sarcoma, MDM2 amplification in dedifferentiated liposarcoma, and H3 G34W mutation in giant cell tumor of bone. Other markers, such as MUC4 in low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma and NKX2.2 in Ewing sarcoma, serve as highly specific diagnostic signatures. In this way, immunohistochemistry has replaced sequencing in many sarcoma subtypes.

When Molecular Testing Is Indispensable?

Despite these advances, there remain categories of sarcoma for which molecular testing is essential. Spindle cell rhabdomyosarcoma, RTK-rearranged spindle cell tumors, CIC-rearranged sarcoma, and round cell sarcomas with EWSR1 non-ETS fusions cannot be reliably diagnosed without sequencing. In such cases, genetic testing is not merely confirmatory but diagnostic.

Rhabdomyosarcoma provides a clear example of why this matters. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma is driven by PAX3/7–FOXO1 fusions and carries a poor prognosis, with survival rates of around forty percent. By contrast, fusion-negative tumors, which are indistinguishable morphologically, behave more like embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and have a significantly better outlook. Here, sequencing provides prognostic clarity, guides treatment planning, and identifies patients eligible for clinical trials. Similarly, gastrointestinal stromal tumors exemplify the therapeutic importance of sequencing, since the choice of targeted therapy depends directly on the presence of KIT or PDGFRA mutations.

When Sequencing Is Not Generally Indicated?

Certain sarcomas are so morphologically distinctive that molecular testing is unnecessary. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, for example, can be diagnosed with high confidence based on morphology and immunohistochemistry alone. Pleomorphic sarcomas similarly rely on histologic features, and sequencing rarely alters management in these cases. A guiding principle is that if sequencing does not change treatment decisions, it should not be undertaken.

Conclusion

The modern diagnosis of sarcoma lies in a careful balance. Morphology and immunohistochemistry remain the cornerstone of practice, with next-generation immunohistochemistry now able to replicate many insights once achievable only through molecular testing. Sequencing plays a crucial but selective role, reserved for sarcoma subtypes where morphology and immunohistochemistry are insufficient, or where genetic results provide essential prognostic or therapeutic information.

Above all, subspecialist pathology review remains central, ensuring diagnostic accuracy and safeguarding patients from misclassification. As therapeutic targets expand, the role of sequencing will continue to grow, but for now, thoughtful integration of these tools is key to optimizing sarcoma care.

You can read the abstract here.