As the global migrant population surpasses 280 million, cancer has become a significant health challenge among immigrant communities worldwide. According to data from the United Nations and the World Health Organization, migrants often face substantial disparities in cancer outcomes due to barriers in accessing timely screenings, diagnosis, and treatment. Studies show that immigrants are up to 16% less likely to be diagnosed with cancer at an early stage compared to native-born populations, leading to poorer prognoses and survival rates.

These disparities are driven by a combination of factors including limited healthcare access, language and cultural challenges, fear of legal repercussions, and socioeconomic disadvantages. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated these inequities by disrupting cancer care services in many immigrant populations.

Photo: Depositphotos

This article explores the complex relationship between immigration and cancer outcomes by presenting key global data from agencies such as WHO, UN, and UNICEF, examining the social and systemic barriers migrants face, and sharing personal stories that highlight their lived experiences. Additionally, it discusses policy measures and innovative interventions such as culturally tailored care programs and improved healthcare navigation that have shown promise in bridging the gap and improving equity in cancer care access. By bringing together evidence and real-world perspectives, this piece aims to shed light on both the challenges and opportunities involved in ensuring immigrant populations receive timely, effective cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Why Are Immigrants Diagnosed at a Later Stage?

Immigrants are consistently less likely to receive an early cancer diagnosis compared to non-immigrants, as demonstrated by a 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis covering OECD countries: migrants were found to be 16% less likely to be diagnosed at an early stage of cancer (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.78–0.91). This disparity is seen across cancer types and regions of origin, though it is particularly pronounced in breast cancer (with foreign-born women being 12% less likely to present at a localized stage, OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.82–0.95).

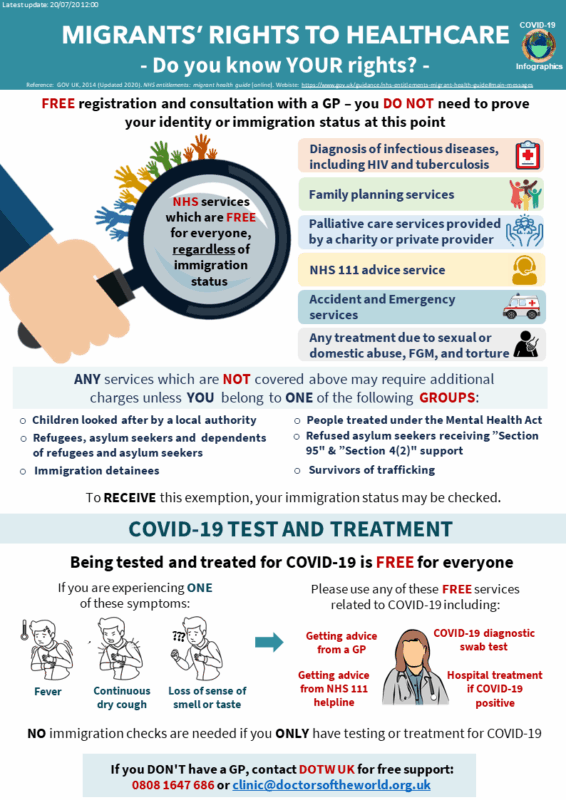

The tendency for later-stage diagnosis among immigrants is attributed to a network of barriers. These include administrative or entitlement restrictions, as many recent immigrants, asylum seekers, or undocumented individuals face delayed or limited eligibility for public health coverage and cancer screening programs. Linguistic and cultural barriers further deter early detection; limited language proficiency and differences in health beliefs can impede understanding of, and willingness to participate in, preventive care or follow-up appointments. Socioeconomic disadvantage compounds these barriers, as immigrants are more likely to experience financial hardship, insurance gaps, unstable employment, or reside in under-resourced neighborhoods where healthcare services and outreach may be limited.

These overlapping challenges structural, economic, linguistic, and cultural create persistent inequities in the cancer care pathway, with diagnostic delays directly elevating risks of late-stage disease and worse survival outcomes.

Which Are The Most Common Cancers In Immigrant Populations?

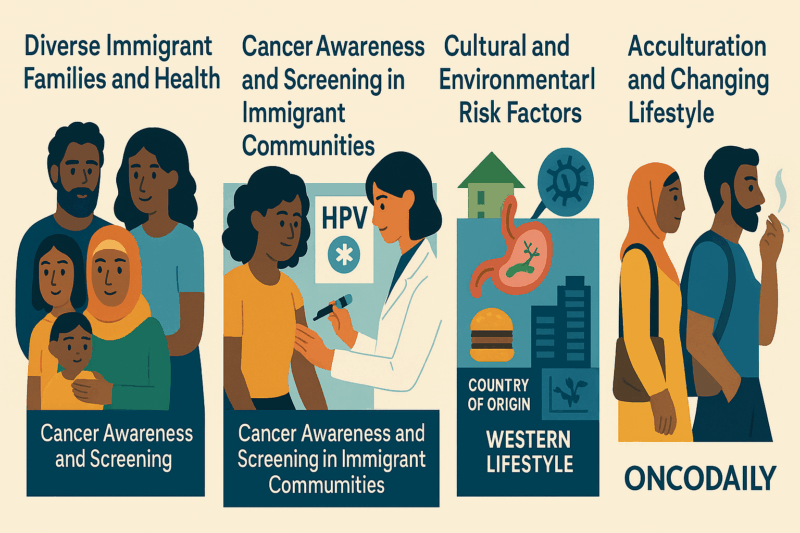

Immigrant populations present unique cancer incidence patterns that reflect both risk factors from their countries of origin and new exposures following migration. When immigrants first arrive in high-income countries such as the United States, Canada, and those in Western Europe, studies show they typically have lower rates of many common solid tumors including breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers than native-born residents. This “healthy immigrant effect” is attributed to selection biases, healthier lifestyles, and different environmental or reproductive exposures before migration.

However, research from agencies like the World Health Organization (WHO) and Public Health England highlights that immigrants bear a disproportionately high burden of infection-related cancers. For instance, rates of stomach (gastric) cancer are often elevated due to earlier exposure to Helicobacter pylori, while liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancers are more frequent among immigrants who contracted hepatitis B or C in childhood or young adulthood. Other cancers such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma (linked to Epstein-Barr virus and traditional dietary practices) and Kaposi’s sarcoma are also more prevalent among certain migrant groups, particularly those from sub-Saharan Africa or Asia. Cervical cancer maintains high incidence among immigrant women, especially if they lacked access to HPV vaccination and screening in their home countries.

Longitudinal cohort studies from Canada and Europe indicate that, over time, as immigrants acculturate and adopt the dietary patterns, tobacco use, and lifestyle behaviors typical of their new country, the risk of “Western” cancers such as lung cancer and colorectal cancer rises and can eventually match or even surpass rates seen in the host population. This gradual shift demonstrates that both infectious exposures from the past and the adoption of lifestyle risk factors after migration play a major role in shaping cancer patterns among immigrants.

These evolving epidemiological trends emphasize the need for cancer control strategies that are carefully adapted to the realities of immigrant communities. Health authorities such as WHO and national cancer agencies advocate for targeted outreach, language-appropriate education around cancer prevention, and improved access to screening and vaccinations (such as hepatitis B and HPV). Such efforts must not only address infection-related risks brought from countries of origin but also anticipate the rising threat of “Western” cancers as immigrant populations adapt their habits over time. Together, these data underscore that effective cancer prevention, early detection, and care for immigrants require policies and interventions responsive to their shifting, dual health risks blending global evidence with culturally tailored local action.

How Has COVID-19 Impacted Cancer Care for Immigrants?

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically intensified existing disparities in cancer care for immigrants and refugees, with mounting evidence from WHO and leading peer-reviewed studies highlighting how these populations were disproportionately affected. Across the globe, cancer screening rates already lower among immigrant communities plummeted even further, as public health resources were diverted and non-urgent services were paused or scaled back. According to WHO, by early 2021, nearly half of countries reported partial or total disruption of cancer services, which meant immigrants relying on overstretched public systems faced routine cancellations or prolonged waiting times for diagnosis and treatment.

The shift to telehealth provided a lifeline for some, but many immigrants struggled to access or use these digital platforms due to technological barriers, limited internet access, and language difficulties, as noted in multiple pandemic-era healthcare reports. Anxiety and uncertainty were compounded by communication gaps and misinformation, leaving many immigrants hesitant to seek care due to fear of infection, job loss, or authorities.

Meanwhile, social determinants such as poverty, precarious employment, and overcrowded housing made it even harder for immigrant cancer patients to manage treatment regimens, self-isolate, or attend appointments. Studies from high-income countries documented that immigrants with cancer had a threefold increased risk of hospitalization and over a fourfold higher risk of death from COVID-19 compared to non-immigrant cancer patients.

Coupled with vaccine access gaps and lower uptake driven by trust issues and informational barriers, the pandemic exposed and widened health inequities, making early detection and continuity of cancer care even more difficult for already vulnerable immigrant populations.

What Drives Cancer Care Disparities Among Immigrants from Low-Resource and Conflict-Affected Regions?

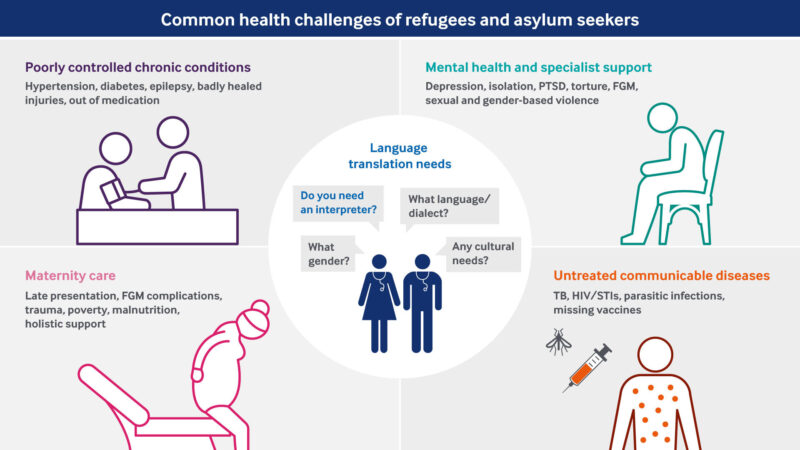

Cancer care disparities among immigrants, particularly those from low-resource, conflict-affected, or disaster-prone countries, are shaped by a complex and interrelated set of systemic and contextual barriers. Infrastructure limitations are common: in many regions of origin where healthcare systems are underfunded or disrupted by conflict, routine cancer screening and specialist services are either severely limited or non-existent, leaving migrants already at a disadvantage upon arrival in host countries.

Even after migration, resource shortages persist, as immigrants, especially recent arrivals face high out-of-pocket costs, unreliable transportation, medication unavailability, and long waiting times that challenge both access to and continuation of care. Legal and status-related barriers further impede care, as lack of insurance coverage, complex eligibility criteria, or fear of deportation or legal consequences discourages undocumented individuals or asylum seekers from engaging with health systems.

Cultural stigma and limited health literacy add another layer: lacking familiarity with cancer prevention, screening practices, or the importance of early detection, many immigrants particularly those with limited language proficiency delay seeking care or misunderstand health recommendations, a pattern reinforced by prevailing community norms and mistrust in healthcare institutions.

Finally, fragmented care pathways are a critical but less visible barrier; limited integration among healthcare, housing, and social support services means that patients can easily fall through the cracks, missing follow-ups or dropping out of care when confronting competing social or economic stressors. These barriers do not act independently, but rather intersect across individual, familial, community, and policy domains, perpetuating lower rates of cancer screening, later-stage diagnoses, and poorer outcomes for immigrant populations.

What Do WHO and UNICEF Data Reveal About Global Cancer Care Disparities Among Migrants and Refugees?

Global data from organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF reveal clear and persistent patterns of cancer care disparities affecting migrants and refugees across high-, middle-, and low-income countries. WHO identifies migrants as a significant and growing segment of the population worldwide, and notes that they commonly have reduced access to cancer prevention, organized screening, and timely treatment services. UNICEF further underscores that child and adolescent migrants experience particular gaps in preventive healthcare, including lower rates of vaccination and essential health education, ultimately increasing their long-term cancer risk.

Epidemiological research from Canada demonstrates a so-called “healthy immigrant effect,” where recent immigrants initially have a lower risk of cancer diagnosis and mortality, as seen in cohort studies using national statistics. However, this advantage erodes over time, typically converging with host population risk and mortality levels after several decades, partly due to growing exposure to local risk factors and healthcare barriers. Large-scale European surveys confirm migrants in all examined destinations are less likely to participate in organized cancer screening programs and are more prone to diagnostic delays and interruptions to treatment.

Studies of forcibly displaced people, such as refugees, indicate that even in countries with universal health coverage, practical access to cancer care is frequently impaired by language barriers, economic hardship, and bureaucratic obstacles even after settlement further widening survival gaps between migrants and non-migrants.Together, these findings highlight both the initial health advantages carried by many new arrivals, and the systemic challenges that erode these gains as migrants encounter inequities in cancer prevention, diagnosis, and long-term outcomes.

How Are Global Health Agencies Transforming Cancer Care Access for Immigrant Communities?

Evidence-based interventions aimed at reducing cancer disparities among immigrants guided by strategies from the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF emphasize comprehensive, patient-centered care that directly addresses the multifaceted barriers these populations face. Culturally competent patient navigation programs, which incorporate multilingual staff and community insiders as navigators, have proven especially effective: these initiatives not only help immigrants schedule and access screenings but also support them in understanding test results and following up on care, with several studies indicating that such interventions nearly eliminate differences in cancer screening uptake for select populations compared to non-immigrants.

Community outreach and education constitute another cornerstone, as leveraging trusted leaders and foreign-trained health professionals to deliver tailored health messages in migrants’ native languages has been shown to substantially improve cancer awareness and foster earlier engagement with prevention and screening services.

The provision of multilingual resources including print, online, and digital tools further enhances access by providing culturally relevant information, timely screening reminders, and interactive support, all critical for overcoming language and digital literacy gaps that could otherwise delay care. Integrated social support systems also play a crucial role, connecting immigrants to essential services such as health insurance enrollment, reliable transportation, mental health support, and stable housing factors which, according to peer-reviewed studies, directly reduce treatment interruptions and improve overall outcomes.

Finally, broader policy innovations that implement universal health coverage and harmonize eligibility rules for migrants and refugees have been associated with more equitable cancer care pathways; countries and regions that have explicitly expanded coverage to include immigrants demonstrate higher rates of preventive screening participation, more consistent access to oncology services, and smaller disparities in cancer outcomes across migrant and non-migrant groups, as documented by international health agencies.

Real-World Perspectives: Barriers and Resilience

Firsthand testimonies from migrant and refugee cancer patients powerfully reveal the multitude of invisible hurdles they confront challenges that go well beyond the clinic walls. Many describe feeling lost within unfamiliar, complex healthcare systems, frequently relying on word-of-mouth or informal networks just to access basic information or book appointments. The compounding pressures of housing insecurity, persistent poverty, language barriers, and the emotional toll of family caregiving during critical illness shape their daily experience. Service providers reinforce these accounts, emphasizing that navigating cancer as an immigrant often requires extraordinary resilience. They underscore the urgent need for:

- Community-based support systems that bridge the gap between health and social care.

- Expansion of service hours and flexibility in appointment scheduling to accommodate non-traditional work patterns.

- Increased recruitment and active inclusion of immigrants and refugees within the healthcare workforce, fostering greater trust and cultural understanding.

- Ongoing mandatory training for providers in cultural competence, trauma-informed care, and anti-discriminatory practices.

You Can Also Read How Aging Populations Are Reshaping Global Cancer Trends or The Silent Shift by Oncodaily

Looking Ahead: Advocacy, Action, and a Call for Equity

The imperative to close the cancer care gap for immigrants is not only a technical challenge, it is a call to collective responsibility and moral action. Achieving true equity demands sustained advocacy and collaboration across local, national, and international levels. Leaders in global health, policy-makers, clinicians, and community organizations must unite to ensure that:

- Every community receives robust, ongoing investment in health infrastructure and workforce development—with a focus on areas serving large migrant and refugee populations, so that disparities are proactively addressed rather than reactively managed.

- Universal, culturally responsive cancer services become a standard, offering linguistically accessible prevention, screening, treatment, and survivorship support tailored to each individual’s needs, regardless of origin or status.

- Research, data, and performance metrics are systematically collected and disaggregated by migration status, allowing for the creation and monitoring of evidence-based strategies that directly target the root causes of inequity and measure real-world progress.

- Digital health innovations and outreach must be prioritized, ensuring that even the most isolated or marginalized migrants have access to information, reminders, and support through technology and community networks.

- Vigorous global advocacy places the needs and realities of migrants, refugees, and displaced people at the center of national and international cancer policies—moving beyond symbolic gestures to concrete commitments and measurable outcomes, aligned with the principles set forth by WHO, UNICEF, and allied organizations

https://www.doctorsoftheworld.org.uk/translated-health-information/

The journey toward equity in cancer care for immigrants is ongoing but the pathway is illuminated by data, shaped by international standards, and strengthened by the lived experiences of those most affected. Now is the moment to turn evidence into action: to champion the cause of every migrant and refugee facing cancer, to reject indifference, and to insist that health justice is achievable across all borders. It is only through coordinated, compassionate, and persistent effort that we can ensure no one’s chance of surviving cancer is determined by where they were born, the passport they carry, or the circumstances of their migration.

Written by Marine Marashlian

FAQ

Do immigrants have different cancer risks than natives?

Yes, cancer risk often changes after migration. Immigrants may initially have risks similar to their country of origin, but over time, their cancer rates tend to rise or fall and may approach those of the new country due to changes in environment and lifestyle.

Is cancer more likely to be diagnosed late in immigrants?

Immigrants are less likely to be diagnosed at an early stage, partly due to lower screening rates, language barriers, and limited access to healthcare. This often results in poorer cancer outcomes.

Does immigration status affect access to cancer care?

Yes, undocumented immigrants and some other groups face significant barriers to accessing timely cancer care, including insurance issues and fear of deportation.

Are there specific cancers more common among immigrants?

Some cancers linked to infections (like liver, stomach, and cervical cancer) are more common among certain immigrant groups, reflecting risks from their country of origin.

How does the length of time in a new country affect cancer risk?

The longer immigrants live in their new country, the more their cancer risk tends to resemble that of the local population, typically due to environmental and lifestyle changes.

How do screening rates among immigrants compare to natives?

Screening rates for cancers like breast, cervical, and colon cancer are generally lower among immigrants, contributing to delayed diagnosis.

How do cancer outcomes differ for immigrants?

Immigrants sometimes have lower cancer-specific mortality—a phenomenon called the “healthy immigrant effect”—but this advantage lessens over time, and access barriers can worsen outcomes for some groups.

Are there disparities in cancer screening among immigrants?

Yes, immigrants generally have lower rates of screening for colorectal, cervical, and breast cancer, contributing to later-stage diagnoses.

Can immigration policies impact ongoing cancer treatment?

Immigration enforcement and policy changes can result in cancer patients being detained or deported during treatment, disrupting care and threatening outcomes.

Do cultural beliefs from an immigrant's country of origin affect cancer care?

Yes, cultural beliefs and practices can strongly influence how immigrants perceive cancer, screening, and treatment. These beliefs may affect willingness to seek care, trust in healthcare providers, and adherence to recommended therapies, sometimes leading to delays or differences in care compared to the native population.