Plastics are everywhere in our daily lives—from packaging and household items to personal care products—making exposure nearly unavoidable. Notably, over 40% of plastics produced globally are used in food packaging, raising concerns about their potential impact on human health. As plastic production and waste continue to surge, emerging research highlights links between plastic-associated chemicals and increased risks of cancer and other chronic diseases. This has led many to ask: does plastic cause cancer? Understanding these risks is crucial as cancer rates rise, particularly among younger populations, underscoring the urgent need to evaluate how ubiquitous plastics may contribute to this growing public health challenge.

Photo: Depositphotos

In this article, we explore different types of plastics, their potential health effects, and evidence-based guidelines for safer use.

Can Plastic Cause Cancer?

Scientific evidence increasingly highlights concerns about the potential carcinogenicity of plastics, primarily due to chemical additives incorporated during plastic production rather than the plastic polymers themselves. Additives such as bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and flame retardants are widely used to enhance plastic flexibility, durability, and fire resistance. These chemicals are often loosely bound within the plastic matrix and can leach out, leading to human exposure through ingestion, inhalation, or dermal contact.

A recent comprehensive toxicogenomic analysis of 2,712 known plastic additives revealed that over 150 have established carcinogenic potential, while approximately 90% lack sufficient data on carcinogenic endpoints. These additives affect biological pathways involved in DNA damage, apoptosis, immune response, and cancer development. BPA and certain phthalates, known endocrine disruptors, have been linked to hormone-related cancers such as breast and prostate cancer, although direct causative evidence in humans remains limited. Sophia Vincoff Environ Sci Technol. 2024.

How Do Chemicals in Plastics Affect Health?

Chemicals in plastics pose health risks through multiple biological mechanisms. Additives like bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and flame retardants can leach from plastics and act as endocrine disruptors, interfering with hormone regulation and potentially promoting cancers and reproductive disorders. Micro- and nanoplastics themselves can be internalized by cells, causing physical damage to cell membranes, inducing oxidative stress, and triggering inflammatory responses.Ilana Belmaker Isr J Health Policy Res. 2024

Endocrine Disruptors

Chemicals such as bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates, widely used as plastic additives, can mimic or block natural hormones by interacting with hormone receptors, thereby disrupting endocrine system functions. BPA acts as an estrogenic compound by binding to estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), altering gene expression and downstream signaling pathways, and also interferes with thyroid hormone receptors, impairing thyroid function Sana Ullah Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023. Phthalates exhibit anti-androgenic effects and disrupt thyroid hormone signaling by antagonizing receptor activity and altering gene expression in the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis. Mensure Nur Celik Curr Nutr Rep. 2025 These disruptions affect critical physiological processes such as reproductive development, metabolism, and cellular growth regulation.

Recent studies show that BPA and phthalates induce epigenetic modifications, including altered DNA methylation of genes like the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which is involved in cell proliferation and placental function, potentially contributing to abnormal cellular growth and cancer risk. Mark Stanojević Arch Toxicol . 2025 Epidemiological and mechanistic evidence links exposure to these endocrine disruptors with increased incidence of hormone-related cancers, particularly breast and prostate cancer, through mechanisms involving hormone receptor modulation, oxidative stress, and inflammation. For example, BPA activates estrogen receptors in mammary and prostate tissues, promoting precancerous and cancerous lesions in animal models. Michele A. La Merrill Nature 2019

While direct causal proof in humans remains limited due to complex exposure patterns and confounding factors, authoritative reviews by organizations such as the World Health Organization emphasize strong correlations between BPA and phthalate exposure and endocrine disruption that may promote carcinogenesis. Continued research is necessary to clarify these links and guide public health policies.

Microplastics and Their Role

Microplastics are tiny plastic fragments, often less than 5 millimeters in size, that enter the human body primarily through contaminated food, water, and air. These particles originate from the breakdown of larger plastic waste and are now pervasive in the environment. Once ingested or inhaled, microplastics can cross biological barriers such as the intestinal lining, blood-brain barrier, and even the placental barrier, allowing them to accumulate in vital organs including the liver, kidneys, brain, and blood. John Dennis, Toxicol Rep. 2025, Marilyn Urrutia-Pereira, J Pediatr (Rio J) 2024

The accumulation of microplastics in the body can provoke oxidative stress, inflammation, and immune system dysfunction. For example, microplastics compromise the intestinal barrier and alter gut microbiota, which is linked to metabolic disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, and colorectal cancer. In the respiratory system, inhaled microplastics can disrupt lung surfactant function and induce pro-inflammatory responses, potentially worsening conditions like asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Moreover, microplastics can act as carriers for environmental pollutants and pathogens, amplifying their toxic effects and contributing to systemic inflammation and cellular damage.

Recent studies have detected microplastics in human blood and multiple organs, confirming their bioaccumulation and raising concerns about long-term health consequences. The presence of microplastics in human tissues correlates with markers of inflammation and oxidative stress, which are known contributors to chronic diseases including cancer. Eliasz Dzierżyńs, Cancer 2024

Although the full extent of health risks remains under investigation, current evidence underscores the urgent need to understand microplastic exposure pathways and mitigate their impact on human health.

Carcinogenic Additives

Flame retardants and stabilizers used as additives in plastics have been increasingly flagged as potentially carcinogenic substances. These chemicals are incorporated into many consumer products to reduce flammability and improve durability. For example, brominated flame retardants (BFRs), a common class of flame retardants, are widely used in electronics, furniture, building materials, and notably in black plastic items such as casings and housings. Lydia G Jahl, Environ Sci Technol. 2025 Jan

Scientific evidence links many flame retardants to adverse health effects including endocrine disruption, immunotoxicity, reproductive toxicity, neurodevelopmental harm, and cancer. BFRs like polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) have been shown to interfere with thyroid hormone function and disrupt endocrine signaling, which can promote carcinogenesis. Haiyan Mao, Nature 2024. Animal studies have demonstrated carcinogenic effects of some flame retardants, and human epidemiological data suggest associations with increased cancer risk, although definitive causal relationships require further research.

Products containing these substances include electronic devices, furniture foam, building insulation, and black plastics such as electrical enclosures and consumer goods. Black plastics often contain higher concentrations of flame retardants to meet fire safety standards, increasing potential exposure. Additionally, flame retardants can migrate out of plastics over time, contaminating indoor dust and the environment, which raises concerns about chronic human exposure, especially in vulnerable populations like children.

Moreover, the combustion or improper disposal of flame-retardant-containing plastics can generate toxic byproducts such as halogenated dioxins and furans, which are recognized carcinogens. These chemicals persist in the environment and bioaccumulate, further amplifying health risks.

Does Heating Food in Plastic Containers Cause Cancer?

Heating or microwaving food in plastic containers significantly increases the risk of harmful chemicals leaching into the food. Studies show that heat accelerates the migration of plastic additives and contaminants-such as bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and PFAS-into food, especially when containers are reused, old, or made from lower-quality plastics. Joseph Pizzorno Integr Med (Encinitas). 2024 May For example, polypropylene (PP) containers, commonly used for food storage, release more chemical leachates when exposed to heat, which can disrupt glucose and lipid metabolism. Similarly, polystyrene (PS) foam containers are not recommended for microwaving due to their higher chemical migration under heat.

Chemical migration is influenced by factors including plastic type, temperature, food composition (fatty or acidic foods increase leaching), and duration of heating or storage. A recent study found that plastic food packaging can release thousands of chemicals, many of which are unknown and some toxic, under realistic use conditions such as heating. Microplastics and nanoplastics may also be released during heating, further contributing to exposure.

To minimize risks, experts recommend avoiding plastic containers for heating food. Safer alternatives include glass, ceramic, or microwave-safe containers explicitly labeled for such use. Using these materials reduces chemical migration and potential health hazards, especially when heating fatty or acidic foods. Additionally, avoiding repeated use of plastics and discarding damaged or scratched containers can help lower chemical exposure .

Is Reusing Plastic Water Bottles Safe?

Reusing plastic water bottles raises two main safety concerns: chemical leaching and bacterial growth. Plastics like polyethylene terephthalate (PET), commonly used in single-use bottles, can degrade over time, especially with repeated washing, mechanical stress, or exposure to heat. This degradation creates tiny cracks and weakens the plastic structure, increasing the likelihood that chemicals such as bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates may leach into the water, potentially posing health risks including hormone disruption and carcinogenic effects.

Photo:Depositphotos

In addition to chemical risks, reused plastic bottles can harbor harmful bacteria. The thin plastic and micro-cracks provide niches where bacteria multiply rapidly, especially if bottles are not washed thoroughly or are left damp. Studies have shown bacterial colonies can increase dramatically within 48 hours at room or body temperature, making contamination a significant health hazard. Washing bottles in hot water or dishwashers can further degrade plastics, exacerbating both chemical leaching and bacterial colonization.

Experts recommend limiting reuse of single-use plastic bottles and advise switching to safer alternatives such as stainless steel, glass, or durable BPA-free plastics designed for repeated use. These materials resist degradation and do not leach harmful chemicals, making them safer for long-term hydration needs. Proper cleaning and drying are essential if plastic bottles are reused, but overall, non-plastic bottles offer a more reliable and health-conscious choice.

Debunking Myths About Plastics and Cancer

Many common beliefs link plastic use to cancer, including claims that all plastics release harmful chemicals, that freezing water in plastic bottles releases dioxins, that BPA-free plastics are completely safe, and that microplastics are too small to impact human health.

Myth: All Plastics Release Harmful Chemicals

Not all plastics contain harmful chemicals; many are specifically designed and regulated to be safe for food contact. Food-grade plastics must comply with strict regulatory standards that limit the migration of substances into food to levels deemed safe for human health. For example, the European Union’s Regulation 10/2011 sets authorized substances and migration limits for plastic food contact materials, ensuring they do not release harmful amounts of chemicals during use. Similarly, regulations like EU Framework Regulation 1935/2004 and FDA guidelines in the U.S. govern the safety of plastics intended for food packaging and storage.

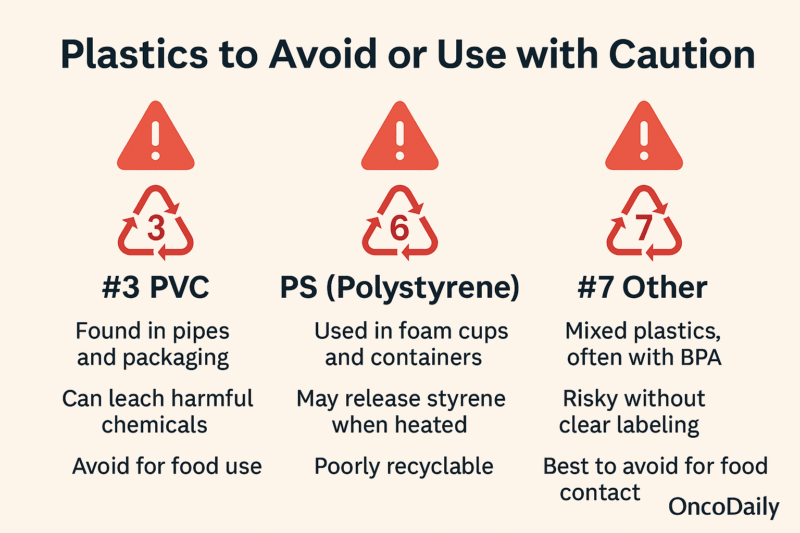

To identify safer plastics, consumers can refer to recycling codes typically found on plastic products. Plastics marked with recycling codes 1 (PET or PETE), 2 (HDPE), 4 (LDPE), and 5 (PP) are generally considered food-safe and less likely to leach harmful chemicals. In contrast, plastics labeled with codes 3 (PVC), 6 (PS), and 7 (Other, including polycarbonate) may contain additives or compounds with potential health risks and are best avoided for food use.

In addition to recycling codes, food-grade plastics undergo rigorous testing for chemical migration using methods such as gas chromatography to detect residual solvents and other contaminants, ensuring compliance with safety limits. Good manufacturing practices (GMP) further guarantee that production processes minimize contamination and maintain the integrity of food-safe plastics.

In summary, choosing plastics with appropriate recycling codes and those certified as food-grade under recognized regulations helps minimize health risks associated with plastic food contact materials.

Myth: Freezing Water in Plastic Bottles Releases Dioxins

The myth that freezing plastic bottles releases dioxins is unfounded and has been repeatedly debunked by scientific experts and health authorities. Dioxins are a group of toxic compounds formed primarily through industrial processes and combustion, not present in plastics such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET), the material commonly used for water bottles. PET bottles do not contain dioxins, and freezing temperatures actually reduce chemical migration rather than increase it, as chemical diffusion slows down in the cold.

This misconception originated from a widely circulated urban legend and an erroneous email falsely attributed to Johns Hopkins University, which claimed that freezing water in plastic bottles causes the release of carcinogenic dioxins. Johns Hopkins researchers and other experts have clarified that this is an urban myth with no scientific basis. Furthermore, reputable fact-checking organizations and public health sources confirm that while plastics can leach some chemicals under heat, dioxins are not among them, and freezing does not trigger any harmful chemical release.

In summary, freezing water in plastic bottles is safe and does not cause the release of dioxins or other dangerous toxins. The persistence of this myth underscores the importance of relying on trusted scientific sources and regulatory agencies such as the FDA and EPA, which affirm the safety of PET plastics under typical use conditions.

Myth: BPA-Free Plastics Are Completely Safe

The widespread belief that BPA-free plastics are completely safe is challenged by recent scientific evidence. A sensitive assay measuring estrogenic activity (EA) found that almost all commercially available plastic products-including those marketed as BPA-free-leach chemicals with estrogenic effects, sometimes even more than BPA-containing plastics, especially after exposure to common-use stresses like microwaving, UV radiation, or autoclaving Charlene Lacourt, Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2024 . These estrogenic chemicals can bind to estrogen receptors and disrupt endocrine functions, potentially contributing to adverse health outcomes such as early puberty, reproductive organ dysfunction, obesity, and increased risks of breast, ovarian, testicular, and prostate cancers.

Importantly, BPA-free plastics often contain alternative monomers and additives (e.g., bisphenol S, bisphenol F, or other proprietary compounds) that have not been fully characterized but may exhibit similar or greater estrogenic activity compared to BPA itself. Studies show that the manufacturing process and environmental stresses can alter chemical structures, creating or increasing estrogenic compounds leaching from BPA-free products. Therefore, BPA-free labeling does not guarantee absence of endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Sarah A Vogel Am J Public Health. 2009

Regulatory agencies continue to evaluate BPA safety, with some recommending lower tolerable daily intake levels due to emerging evidence of low-dose effects. However, the complexity of plastic formulations and the presence of multiple chemicals with unknown activities complicate risk assessment.

Myth: Microplastics Are Too Small to Impact Human Health

Microplastics (MPs)-tiny plastic particles less than 5 millimeters in size-can enter the human bloodstream primarily through ingestion of contaminated food and water, as well as inhalation of airborne particles. These particles traverse biological barriers such as the intestinal lining and lung epithelium via processes like endocytosis, allowing them to circulate systemically. Once in the bloodstream, MPs are phagocytosed by immune cells, forming what are termed MPL-Cells, which can accumulate and obstruct small blood vessels, particularly in the brain cortex. Haipeng Huang, Sci Adv. 2025.

Advanced imaging studies in animal models have demonstrated that these MPL-Cells cause microvascular obstructions that reduce blood perfusion, leading to impaired neurological function and increased risk of cerebral thrombosis. MPs have also been detected in human blood samples, with studies showing associations between microplastic presence and altered coagulation markers, suggesting potential impacts on cardiovascular health. Furthermore, nanoscale plastics can cross the blood-brain barrier, raising concerns about neurotoxic effects and long-term brain dysfunction.

Beyond the bloodstream, MPs accumulate in various organs including the liver, kidneys, lungs, and placenta, where they can induce chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and immune dysregulation. These biological responses contribute to tissue damage and may increase risks for metabolic, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases over time. Although human epidemiological data are still emerging, the mechanistic evidence from recent studies highlights the potential for microplastics to cause long-term adverse health effects through persistent accumulation and vascular obstruction. Dong-Wook Lee Nature 2024.

In summary, microplastics enter the bloodstream via ingestion and inhalation, accumulate in immune cells that can obstruct blood vessels, especially in the brain, and induce inflammation and oxidative stress in multiple organs. These processes pose significant long-term health risks, emphasizing the urgent need for further research and mitigation strategies.

How to Reduce Exposure to Harmful Chemicals from Plastics

To minimize potential risks associated with plastic use, practical steps focus on reducing exposure, choosing safer materials, and supporting sustainable practices.

Choosing Safer Plastics

When selecting plastics free from harmful additives, understanding recycling codes and their safety profiles is essential. Plastics are labeled with Resin Identification Codes (numbers 1 through 7) that indicate their polymer type and recyclability, helping consumers choose safer options.

Are Recycled Plastics and Heat Exposure Safe for Everyday Use?

Recycled plastics have been found to contain higher levels of hazardous substances such as PFAS, polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and metal contaminants compared to virgin plastics. While proper decontamination during recycling can reduce these risks, chemical safety remains a concern—particularly with recycled PET. Heat exposure further accelerates the migration of chemicals from plastics, increasing potential harm. To minimize risk, only use plastics labeled as microwave-safe and avoid heating those not intended for high temperatures.

Avoiding Heat and Plastic

To minimize health risks associated with plastics, it is strongly recommended to avoid heating food in plastic containers or leaving plastic water bottles exposed to hot environments. Heat accelerates the leaching of harmful chemicals like bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and other additives from plastics into food and beverages, increasing potential exposure to endocrine disruptors and toxins.

Instead, opt for safer alternatives such as:

- Glass containers: Non-reactive, durable, and ideal for heating and storage. Glass does not leach chemicals and is microwave and dishwasher safe.

- Stainless steel bottles and containers: Highly durable, resistant to heat, and free from chemical leaching. Perfect for both hot and cold beverages.

- Food-grade silicone: Flexible, heat-resistant, and safe for food storage and reheating. Silicone is BPA-free and does not release harmful substances under typical use conditions.

Using these materials helps reduce chemical exposure and supports healthier food and beverage storage practices.

Alternatives to Plastic Products

Here are sustainable alternatives for common plastic items that prioritize safety, durability, and environmental responsibility, along with examples of trusted brands and products:

Glass Food Storage Containers

Glass is a non-toxic, durable material that doesn’t leach harmful chemicals, making it an excellent choice for food storage and reheating. Most glass containers are safe for use in the oven, microwave, freezer, and dishwasher. Brands like Caraway offer ceramic-coated glass containers that are free from BPA, BPS, PFOA, PTFE, heavy metals, and other toxic substances.

Their sets include airtight lids with Air Release Technology to keep food fresh. Pyrex Freshlock and Snapware Total Solution are popular for their heat-resistant borosilicate glass, ideal for versatile storage. Biome Glass Containers are BPA-, PVC-, and phthalate-free, combining safety with a clean, modern design. Even old glass jars from food products offer a zero-waste, budget-friendly alternative to plastic, perfect for leftovers or pantry storage.

Reusable Cloth Bags

Replacing single-use plastic bags with reusable cloth alternatives helps reduce plastic waste and minimizes exposure to harmful plastic additives. Lotus Sustainables offers durable, insulated bags with smart features like pockets and removable rods—their Lotus Trolley Bag aims to replace billions of disposable bags. Veno Bags creates reusable grocery, produce, and insulated bags using 80% post-consumer recycled materials. Baggu emphasizes low-waste design with products made from recycled nylon, canvas, and mesh, and even offers recycling programs for old bags. Eco-Bags Products, a pioneer since 1989, has long promoted sustainable living through affordable, high-quality reusable bags.

You Can Also Read Does 5G Mobile Network Cause Cancer? Myths and Facts by Oncodail

Environmental Impact of Plastics and Health

Plastic pollution significantly contributes to microplastic contamination in the environment, which indirectly impacts human health through complex ecological pathways. Improper management of plastic waste leads to widespread dispersion of plastic debris, with plastics comprising 60–80% of marine litter and 90% of floating ocean waste. Over time, larger plastic items fragment into microplastics-particles smaller than 5 millimeters-that persist in ecosystems due to their synthetic, non-degradable nature.

Microplastics contaminate freshwater, marine, and terrestrial environments, entering food chains at multiple levels. Aquatic organisms, including plankton, fish, and shellfish, ingest microplastics either directly or indirectly, mistaking them for food. This ingestion disrupts feeding patterns, growth, and reproduction in marine species, causing toxic effects that propagate up the food web. Microplastics also carry hydrophobic organic pollutants and additives, which can bioaccumulate and biomagnify, increasing exposure risks for higher trophic levels, including humans who consume seafood.

Photo: Depositphotos

Did you know? Sea turtles often mistake plastic bags for jellyfish and eat them, which can block their stomachs and be deadly.

Emerging research highlights that microplastic pollution affects key ecosystem functions beyond individual species. For example, microplastics alter microbial communities in aquatic sediments, disrupting nitrogen cycling and nutrient flows essential for ecosystem health. Such changes can exacerbate harmful algal blooms and oxygen depletion in ocean waters, further stressing marine life and food resources. Additionally, microplastics transported by sinking plankton feces can impact deep-sea organisms vital for nutrient recycling and carbon sequestration, potentially influencing global biogeochemical cycles and climate regulation.

Photo: Deposithotos

Terrestrial environments are also heavily contaminated; studies estimate that microplastic pollution in soils and freshwater may be four to 23 times higher than in marine systems. Microplastics enter soils through plastic waste degradation and sewage sludge application, subsequently infiltrating terrestrial food chains via crops and soil organisms. This widespread environmental presence raises concerns about human exposure through multiple pathways, including ingestion of contaminated food and water, inhalation of airborne particles, and dermal contact.

Human health implications are increasingly evident. Microplastics have been detected in human organs such as the liver, kidneys, and placenta, indicating systemic exposure. Animal studies show microplastics can induce inflammation, oxidative stress, and vascular obstruction, with potential links to cardiovascular, neurological, and reproductive disorders. While direct causal relationships remain under investigation, the persistence and bioaccumulative nature of microplastics, combined with their capacity to carry toxic chemicals, underscore substantial risks.

Iris Van Herpen creates haute couture dress from ocean plastic.

Are There Safe Ways to Use Plastics?

To use plastics safely, follow key guidelines based on scientific evidence and manufacturer advice. Choose food-grade plastics with recycling codes 2 (HDPE), 4 (LDPE), or 5 (PP), which have low risks of chemical leaching. Avoid codes 3 (PVC), 6 (PS), and 7 (Other), as they may release harmful chemicals, especially when heated. Use code 1 (PET) plastics only once, as reuse or heat can degrade them and increase leaching. Never heat plastics unless they are labeled microwave-safe—prefer glass, ceramic, or stainless steel for reheating.

Inspect containers regularly and discard those that are scratched, cracked, or warped. Hand wash plastics unless marked dishwasher-safe, and clean grooves and lids thoroughly to reduce bacterial risks. Only freeze food in containers labeled freezer-safe. When possible, choose certified food-safe products approved by the FDA or similar bodies, and opt for safer materials like glass, stainless steel, or silicone, which offer better durability and chemical safety.

Call to action: Stay informed about plastic-related health and environmental issues, critically evaluate your plastic use, and embrace sustainable alternatives. Support policies and innovations aimed at reducing plastic pollution and promoting safer materials. Together, we can foster a healthier future by balancing the benefits of plastics with conscious, responsible choices.

You Can Also Read Do Artificial Sweeteners Cause Cancer? Myths and Facts by Oncodaily

You Can Also Listen Does Processed Meat Cause Cancer? Myths and Facts: OncoDaily DeepDive

Call to action

Stay informed about plastic-related health and environmental issues, critically evaluate your plastic use, and embrace sustainable alternatives. Support policies and innovations aimed at reducing plastic pollution and promoting safer materials. Together, we can foster a healthier future by balancing the benefits of plastics with conscious, responsible choices.

Written by Aharon Tsaturyan MD

FAQ

What are the health risks associated with plastics used in food packaging and containers?

Plastics can leach harmful chemicals such as bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and other additives into food and beverages, especially when heated or damaged. These chemicals are endocrine disruptors linked to hormone imbalance, reproductive issues, developmental disorders, and increased cancer risk (breast, prostate).

What is Bisphenol A (BPA) and why is it a concern?

BPA is a chemical used in hard plastics and can linings that mimics estrogen, potentially disrupting hormone function. Exposure is especially concerning for infants and young children, as it may affect development and fertility. Although most adults have low exposure, heating BPA-containing plastics can increase leaching (e.g., baby bottles, canned food linings).

How do microplastics affect human health?

Microplastics enter the human body through ingestion, inhalation, and skin contact. They can accumulate in organs and carry toxic chemicals and pathogens. Studies link microplastic exposure to inflammation, oxidative stress, respiratory problems, and potential long-term risks such as cancer and developmental impairments.

Are all plastics equally harmful? How can I identify safer plastics?

Not all plastics pose the same risks. Plastics labeled with recycling codes #1 (PET), #2 (HDPE), #4 (LDPE), and #5 (PP) are generally safer for food contact. Plastics with codes #3 (PVC), #6 (PS), and #7 (Other) may contain more toxic additives and should be avoided for food use.

How can I reduce my exposure to harmful chemicals from plastics?

Avoid heating food in plastic containers unless labeled microwave-safe, do not reuse single-use plastics extensively, choose BPA-free and certified food-safe plastics, and prefer alternatives like glass or stainless steel. Proper disposal and supporting plastic waste reduction also help minimize environmental contamination and indirect exposure.

Can chemicals in plastics cause cancer?

Yes. Plastics contain chemicals such as bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, vinyl chloride, dioxins, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that have been linked to cancer development. These substances can act as endocrine disruptors, cause DNA damage, and promote oxidative stress, increasing the risk of cancers including breast, ovarian, liver, and lung cancer.

How do microplastics contribute to cancer risk?

Micro- and nanoplastics can enter the human body via ingestion or inhalation and accumulate in organs. They induce oxidative stress, inflammation, and cellular apoptosis, which may lead to carcinogenesis. Research shows correlations between exposure to microplastics and cancers such as hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic cancer, though studies are ongoing to clarify mechanisms.

Is using plastic bottles and containers safe, or do they cause cancer?

Current evidence suggests that chemical migration from plastic containers into food or drink is generally at low levels unlikely to cause cancer under normal use. However, heating plastics or using damaged containers can increase chemical leaching. Choosing BPA-free and food-grade plastics and avoiding heat exposure reduces risk. Regulatory agencies maintain that plastics used as intended do not pose a significant cancer risk

How much plastic waste is produced and recycled globally?

About 91% of plastic waste worldwide is not recycled and ends up in landfills or the environment, including oceans. Plastic production has surged from 2 million tonnes in 1950 to over 460 million tonnes annually by 2019, with single-use plastics accounting for about 50% of production.

How much plastic pollution is currently in the oceans?

There are an estimated 75 to 199 million tonnes of plastic waste in the oceans today, with about 33 billion pounds entering marine environments every year. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch alone contains roughly 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic, covering an area twice the size of Texas.

Which countries contribute most to plastic pollution?

Nearly 70% of global plastic pollution is generated by just 20 countries. India, now the most populous country, leads with about 20% of the world’s plastic waste, followed by Nigeria, Indonesia, China, and Pakistan. Asia accounts for 81% of ocean plastic pollution due to high population and inadequate waste management