Amol Akhade, Consultant Medical Oncologist at Suyog Cancer Clinics, shared a post on X:

“Hi all.

Did one new experiment on oncology social media. Made my account on Substack and uploaded my article to it. If you find it useful, DO share or subscribe, and comment.

Do check out my post on Substack about the Matterhorn Trial.

Immunotherapy in Gastric Cancer: One Win, Five Losses, and a Biomarker Lesson.

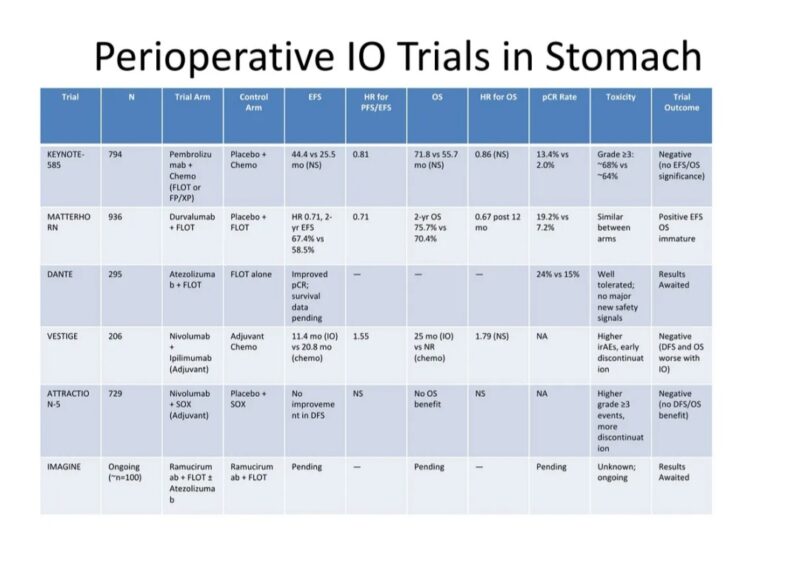

In the evolving landscape of gastric and gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) cancer, perioperative therapy remains a cornerstone. For years, chemotherapy has been the mainstay, with trials like MAGIC and FLOT setting expectations for how far survival can be pushed with cytotoxic combinations. The question was simple, almost inevitable: can we do better with immunotherapy?

The early hope was seductive. After all, immune checkpoint inhibitors had revolutionized treatment in several cancers. In the metastatic setting, their impact was undeniable in MSI-high gastric tumors. Could this success be translated into the curative intent setting? A wave of phase II and III trials sought to answer that. The answer, unfortunately, has been mostly disappointing – with one sharp exception.

The Chemo Era: What MAGIC, FLOT, and ESOPEC Taught Us

Before we examine the immune era, it’s worth remembering what we achieved with chemotherapy alone. The landmark MAGIC trial – a UK-led study of ECF (epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-FU) – was the first to show that perioperative chemo could improve outcomes over surgery alone. Five-year overall survival increased from 23% to 36%. It was a modest, but meaningful step forward.

Then came FLOT4, which raised the bar. Replacing ECF with a docetaxel-based FLOT regimen (5-FU, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, docetaxel), the trial showed a clear survival benefit: 5-year OS improved from 36% to 45%, and pathologic complete response (pCR) jumped from 6% to 16%.

The ESOPEC study and subsequent real-world data suggested even higher survival rates, with 5-year OS reaching ~57% in selected cohorts. FLOT became the new standard. So when immunotherapy entered the scene, it wasn’t because chemotherapy had failed – it was because we wanted to push the boundaries further.

The Immunotherapy Wave: A Flood of Disappointment

Over the past five years, six non-MSI-selective IO trials tested whether immune checkpoint inhibitors could improve on FLOT or similar chemotherapy regimens. Most failed. Only one – MATTERHORN – succeeded. The rest either showed no benefit, or worse, possible harm. It’s a pattern that deserves closer scrutiny.

KEYNOTE-585, the much-anticipated phase III trial adding pembrolizumab to perioperative chemo, offered early promise with a bump in pCR rates (13.4% vs 2.0%). But that never translated into survival benefit. Event-free survival (EFS) showed a trend (HR 0.81) but didn’t meet statistical significance.

OS was numerically better (71.8 vs 55.7 months) but again, not significant. Subgroup analyses suggest the faint benefit seen was largely confined to patients with high PD-L1 expression (CPS ≥10). In contrast, PD-L1 low or negative tumors (CPS <1%) did not derive any benefit, potentially diluting the overall signal. Without stratification by biomarker status, the trial suffered from biological noise.

DANTE, a phase II study of atezolizumab added to FLOT, showed a more promising increase in pCR – 24% vs 15% – especially among PD-L1 high and MSI-high patients. But for PD-L1–negative tumors, response was limited. Without survival data, it remains a promising but incomplete story.

VESTIGE was even more sobering. This European trial explored adjuvant nivolumab and ipilimumab after neoadjuvant chemo and surgery in high-risk patients. The hypothesis was bold: can IO replace post-op chemotherapy? The results were unequivocal.

DFS was worse in the immunotherapy arm (11.4 months vs 20.8 months), and the trial was halted for futility. PD-L1 was not used as a stratification factor. Presumably, the lack of biomarker selection allowed nonresponsive tumors – many of them PD-L1 negative – to flood the trial with null outcomes.

ATTRACTION-5, conducted in Asia, added nivolumab to adjuvant chemotherapy in stage III gastric cancer post-D2 resection. It failed to show benefit. DFS and OS were unchanged, and toxicity increased. Again, no stratification by PD-L1. No surprise it was negative.

IMAGINE, an early-phase trial of ramucirumab and FLOT ± atezolizumab, hasn’t reported survival results yet. For now, it’s more idea than evidence.

What About IO in Advanced or Metastatic Disease?

Outside the perioperative setting, immunotherapy has had a longer and more complex history in advanced gastric and GEJ cancer. In the first-line metastatic setting, the addition of a PD-1 inhibitor to chemotherapy has shown survival benefits – but only in biomarker-selected patients.

Trials like KEYNOTE-859 and CheckMate-649 established pembrolizumab or nivolumab, respectively, as frontline partners to chemotherapy – but only for tumors with PD-L1 CPS ≥5 or higher. For PD-L1–negative tumors, the benefit is unclear at best, and these patients were often underrepresented or poorly characterized in subgroup analyses. Regulatory approvals (e.g., FDA, EMA) vary, and practice patterns reflect that ambiguity.

In the second-line or later settings, the evidence becomes even thinner. The KEYNOTE-061 and ATTRACTION-2 trials examined pembrolizumab and nivolumab in previously treated patients. Here too, responses were modest, with objective response rates hovering around 6% to 15% – and again, almost entirely driven by PD-L1 positive tumors.

In PD-L1 negative, immune checkpoint inhibitors offer little benefit, if any, beyond placebo. And yet, in many parts of the world, IO continues to be prescribed in second line with little biomarker selection – an uncomfortable gap between data and practice.

What this tells us is consistent with what perioperative trials have shown: the immune system can be a powerful ally – but only in the right biological context. For PD-L1 negative, MSS gastric cancer, chemotherapy remains the backbone. IO, in such cases, is still chasing relevance.

Why Did They All Fail – Except One?

MATTERHORN, a global phase III trial, is the outlier. It tested perioperative durvalumab + FLOT followed by adjuvant durvalumab vs FLOT alone in resectable gastric/GEJ adenocarcinoma. The results were clear and, for once, statistically robust. Event-free survival improved with a hazard ratio of 0.71. OS improved too – HR 0.78 – crossing the significance threshold. pCR improved from 7% to 19%. Toxicity remained manageable.

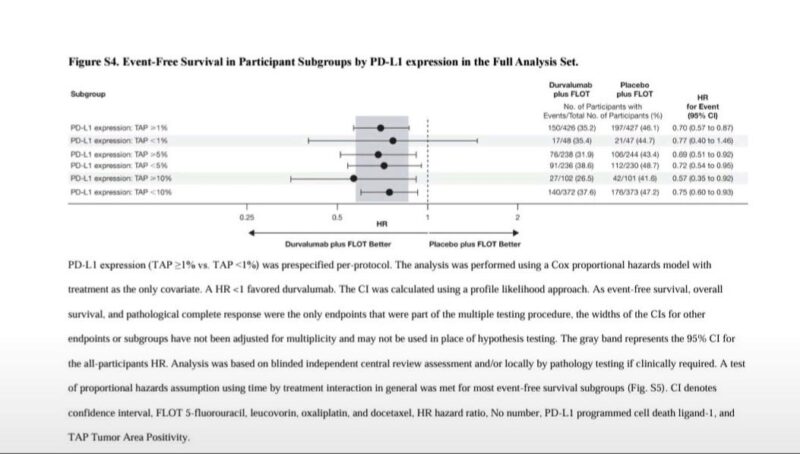

But what truly separates MATTERHORN is the attention to PD-L1 biology. The trial stratified by tumor area positivity (TAP), a more precise measurement than CPS. It showed that patients with PD-L1 TAP ≥1% clearly benefited from durvalumab. But those with PD-L1 TAP <1% – roughly 10% of the study population – saw no benefit at all. In fact, the FLOT-alone arm performed slightly better in this subgroup (HR ~0.77, p=0.533). This is not a gray zone. It’s a red flag.

What does this mean? It means MATTERHORN was a positive trial – but only for the right patients. When immunotherapy works, it works well. When it doesn’t, it offers nothing but added toxicity and cost.

Why MATTERHORN Worked – and KEYNOTE‑585 Didn’t: It’s About FLOT?

One of the most critical differences between MATTERHORN and KEYNOTE‑585 lies in chemo backbone consistency.

In MATTERHORN, 100% of participants received the FLOT regimen – both as neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy. Every patient received four cycles of FLOT perioperatively, followed by 10 cycles of maintenance durvalumab or placebo. This ensured a uniform cytotoxic backbone, making it easier to isolate the effect of adding immunotherapy to the regimen.

By contrast, in KEYNOTE‑585, although it included a FLOT cohort, only about 20% of enrolled patients were assigned to the FLOT backbone. The majority (~80%) received cisplatin‑based doublets (capecitabine or 5‑FU plus cisplatin) that have historically underperformed compared to FLOT.

Even within that small FLOT subgroup, only ~45% completed the planned adjuvant treatment, compared with 63% completion in MATTERHORN. This inconsistency diluted efficacy signals and made the trial underpowered to detect survival benefit from pembrolizumab addition.

In simpler terms: MATTERHORN leveraged the most effective chemo regimen available (FLOT) in every patient and followed through; KEYNOTE‑585 partially used FLOT and had lower adherence – making it harder for IO to show meaningful impact.

Censoring Alert: Is the EFS Signal in MATTERHORN Overstated?

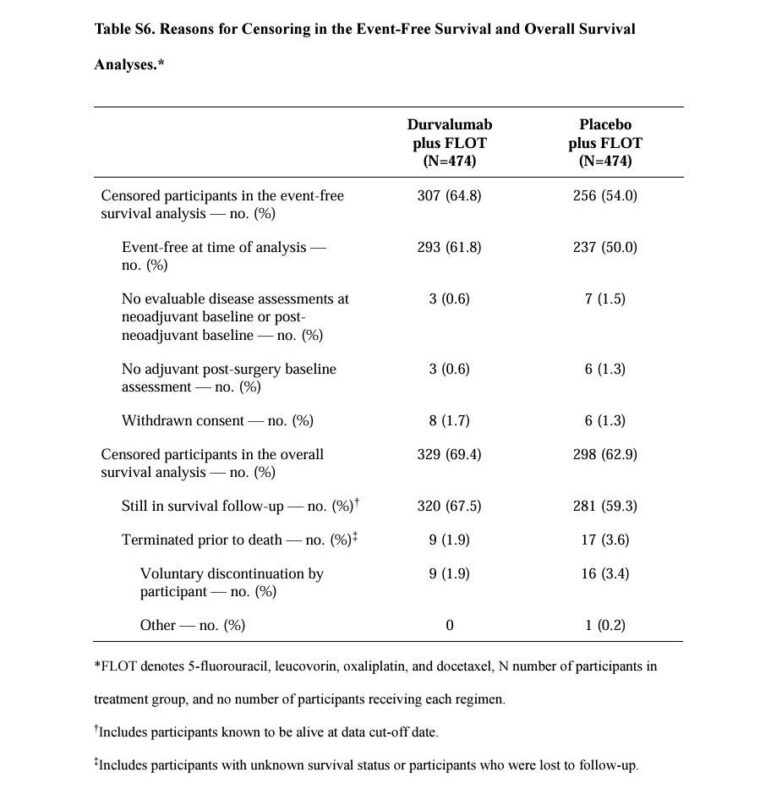

While MATTERHORN’s headline EFS hazard ratio of 0.71 looks impressive, the underlying data raises concerns about informative censoring. In the durvalumab arm, a striking 64.8% of patients were censored, compared to 54.0% in the placebo arm.

Most of this censoring occurred because patients were event-free at data cut-off – not due to prolonged follow-up. This introduces potential bias. The Kaplan–Meier curves flatten after 24 months, but with fewer than 20 patients at risk, the tail end is statistically unstable. The median EFS for durvalumab was ‘not reached,’ yet the lower bound of the confidence interval is just 40.7 months – barely ahead of the 32.8 months in the control arm.

Only 167 vs 218 events were observed at this interim analysis. All of this suggests the modest 24-month EFS difference (67% vs 59%) could be exaggerated. Until mature OS data arrives, it’s premature to call MATTERHORN practice-changing without caveats.

Should This Change Practice?

Yes – with precision.

The MATTERHORN trial is the first to convincingly demonstrate that perioperative immunotherapy can improve survival in resectable gastric cancer when layered onto a strong chemotherapy backbone. It is not just a pCR win. It is a survival win. That justifies its label as practice-changing – for patients with PD-L1–expressing tumors.

But here’s the danger: generalizing beyond the data. We’ve seen this before – across tumor types, the moment a positive IO trial drops, the temptation to offer it to all patients is irresistible. But here, the data is explicitly cautioning us: PD-L1 negative patients don’t benefit. Giving IO to them may waste resources, deliver false hope, or worse – introduce harm.

This caution is reinforced by the failures of KEYNOTE‑585, VESTIGE, and ATTRACTION‑5 – all of which included PD-L1 negative tumors without stratification and suffered as a result.

Final Take

Perioperative IO in gastric cancer looked promising – until it wasn’t. Five trials failed. One succeeded. That one, MATTERHORN, tells us what’s possible when good design meets biological plausibility and patient selection.

The future isn’t perioperative IO for all – it’s IO for the right patients, with the right biomarkers, and the right timing.

For PD-L1–positive tumors, durvalumab + FLOT may be a new standard. For PD-L1–negative tumors, FLOT remains the standard of care.”

More posts featuring Amol Akhade.