Careful scientists know to acknowledge uncertainty in the findings and conclusions of their papers. But in one leading journal, the frequency of hedging words such as “might” and “probably” has fallen by about 40% over the past 2 decades, a study finds.

If this trend holds across the scientific literature, it suggests a worrisome rise of unreliable, exaggerated claims, some observers say. Hedging and avoiding overconfidence “are vital to communicating what one’s data can actually say and what it merely implies,” says Melissa Wheeler, a social psychologist at the Swinburne University of Technology who was not involved in the study. “If academic writing becomes more about the rhetoric … it will become more difficult for readers to decipher what is groundbreaking and truly novel.”

The new analysis, one of the largest of its kind, examined more than 2600 research articles published from 1997 to 2021 in Science, which the team chose because it publishes articles from multiple disciplines. (Science’s news team is independent from the editorial side.) The team searched the papers for about 50 terms such as “could,” “appear to,” “approximately,” and “seem.” The frequency of these hedging words dropped from 115.8 instances per 10,000 words in 1997 to 67.42 per 10,000 words in 2021.

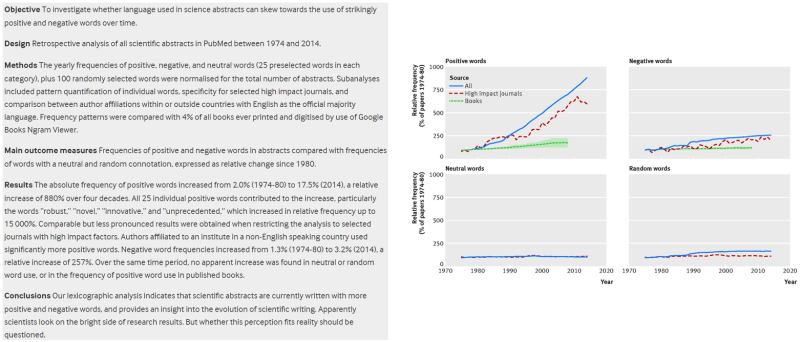

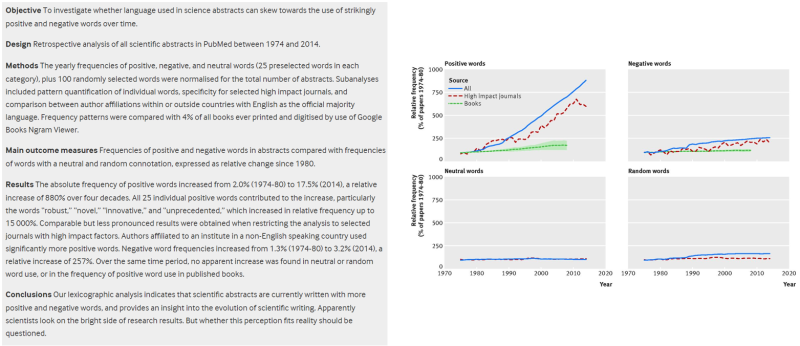

The study adds to other findings suggesting an increasing reluctance to undersell one’s research in a competitive academic world. A study below that examined nearly the same group of papers from Science have found growing use of a positive, promotional tone, expressed in superlatives such as “groundbreaking” and “unprecedented”, which may lead to exaggerated claims:

Less hedging may reflect a subtle strategy by authors to sell their results to editors and readers as an alternative to explicit exaggeration, according to the study, published in the August issue of Scientometrics. That should concern scientists, says co-author Ying Wei, a linguist at Nanjing University, because “essentially, the nature of academic knowledge is indeterminate.”

Authors may be hedging less because editors have increasingly asked authors to supply additional supporting information. The Scientometrics findings may also reflect a move by the editors away from older conventions of scientific writing that encouraged hedging and passive voice, she says. That style has given way to a more modern, informal tone marked by less hedging. To avoid exaggeration, “we tone down language if it comes across as definitive when [the evidence] is not,” the Editor of Science Dr Vinson said.

Vinson also notes that the Scientometrics study looked only at papers published in the Research Article format, which used to be reserved for a few landmark papers that may have been especially likely to hedge. During the study period, Science increasingly shifted more findings to the Research Articles format.

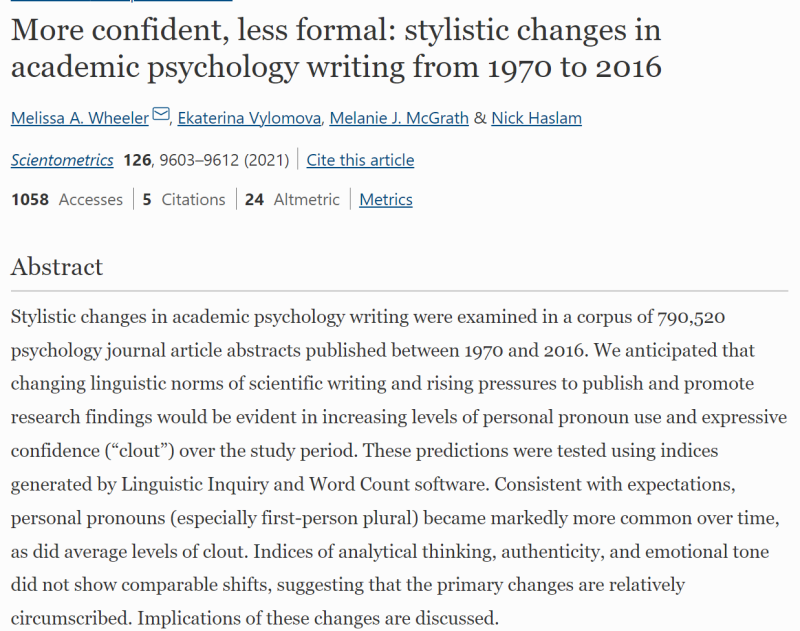

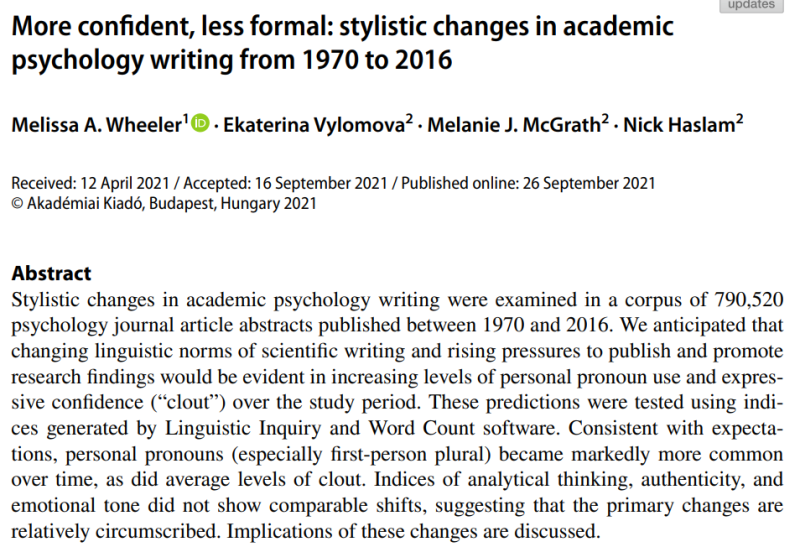

A more informal writing style in research papers may have an upside if it makes them more understandable to policymakers and the public, Wheeler says. She and colleagues came to that conclusion in a 2021 Scientometrics study that analyzed the abstracts of nearly 800,000 articles published in psychology journals between 1970 and 2016. But the study also red flags a 24% increase during that period for ‘clout’ This linguistic measure reflects language similar to “in my expert opinion,” that is confident and authoritative, perhaps in some cases too confident:

Although journal editors and reviewers should look out for exaggerated claims, they shouldn’t bear all the responsibility, Wheeler cautions. “It’s also up to universities and research institutes to value the quality over quantity of researchers’ outputs,” she says, “which would allow more time for academics to reflect and produce meaningful work instead of churning out as many publishable papers as possible.”

Wei adds a hedge of her own, however: The new study doesn’t show what caused the observed decline of hedging language. The pressure to publish that academics face to gain tenure, promotion, and professional recognition may play a role, but there could be other factors as well. The nature of the connection, she says, deserves further study.

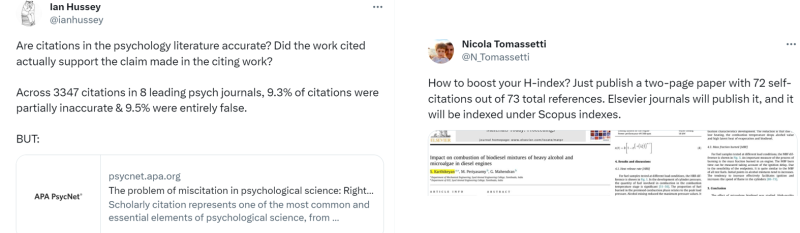

Next, you know that feeling when you click a link in an article which ostensibly backs up some claim or other, and you can’t find any reference to it in the link – or even find that the link says the opposite? Well, it happens in scientific papers too, in fact a lot. A recent study examines citations in psychology papers, and finds that 9.3% of are a bit wrong, and a further 9.5% completely misrepresent the research they’re apparently citing. Checking citations is another thing peer-reviewers would, in a perfect world, be doing, but of course they don’t have the time. Could flagging up dodgy citations be a future job for GPT? Ian Hussey looked at the raw data in a Twitter thread and found that misleading citations ranged from 0 to 50%, and completely misleading ones from 0 to 30%. Who on Earth is reviewing the papers where a third of the citations are completely wrong?!

Scientists Behaving Badly update: not only was there a story in El Pais about the Spanish chemistry researcher who publishes a paper every 37 hours(!?) who has now been “suspended without pay for 13 years”, but the physicist Nicola Tomasetti has been tweeting some incredible examples of scientists self-citing to an absurd extent, clearly in an attempt to game the system and boost their h-index:

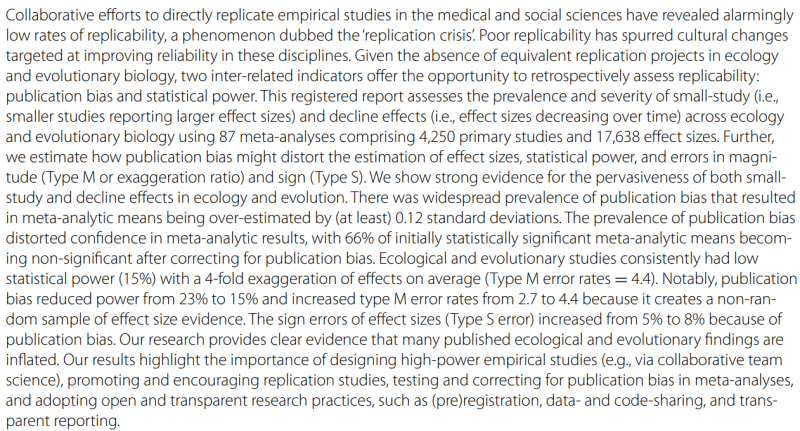

Something I’ve often wondered: why is it that certain scientific fields get the “replication crisis” bug and others don’t? Obviously, psychology and to a large extent neuroscience have been affected, as well as parts of economics and medical research. Another field that seems to have a disproportionate amount of self-critical stuff, much to its credit, is ecology & evolution. I guess just by luck a few papers appear, and then you have path-dependency effects where other people within the field start looking at the same thing. A recent ecology paper concludes that many findings in that area “are likely to have low replicability:

Also, careful scientists know to acknowledge uncertainty in the findings and conclusions of their papers. But in one leading journal, the frequency of hedging words such as “might” and “probably” has fallen by about 40% over the past 2 decades, a study finds.

If this trend holds across the scientific literature, it suggests a worrisome rise of unreliable, exaggerated claims, some observers say. Hedging and avoiding overconfidence are vital to communicating what one’s data can actually say and what it merely implies. If academic writing becomes more about the rhetoric…it will become more difficult for readers to decipher what is groundbreaking and truly novel.”

The new analysis, one of the largest of its kind, examined more than 2600 research articles published from 1997 to 2021, which the team chose because it publishes articles from multiple disciplines. (Science’s news team is independent from the editorial side.) The team searched the papers for about 50 terms such as “could,” “appear to,” “approximately,” and “seem.” The frequency of these hedging words dropped from 115.8 instances per 10,000 words in 1997 to 67.42 per 10,000 words in 2021.

The study adds to other findings suggesting “an increasing reluctance to undersell one’s research in a competitive academic world. Another earlier paper that examined nearly the same group of papers found growing use of a positive, promotional tone, expressed in superlatives such as “groundbreaking” and “unprecedented”, which may lead to exaggerated claims:

Less hedging may reflect a subtle strategy by authors to sell their results to editors and readers as an alternative to explicit exaggeration, according to the study. That should concern scientists, says co-author Ying Wei, a linguist at Nanjing University, because “essentially, the nature of academic knowledge is indeterminate.”

Science’s expectations that manuscripts provide reliable evidence didn’t drop during the study period, says Executive Editor Valda Vinson, who joined the journal in 1999. She suggests authors may be hedging less because editors have increasingly asked authors to supply additional supporting information. The findings may also reflect a move by the editors away from older conventions of scientific writing that encouraged hedging and passive voice, she says. That style has given way to a more modern, informal tone marked by less hedging. To avoid exaggeration, “we tone down language if it comes across as definitive when [the evidence] is not,” she adds.

Vinson also notes that the study looked only at papers published in the Research Article format, which used to be reserved for a few landmark papers that may have been especially likely to hedge. During the study period, Science increasingly shifted more findings to the Research Articles format.

A more informal writing style in research papers may have an upside if it makes them more understandable to policymakers and the public, Wheeler says. She and colleagues came to that conclusion in a 2021 study that analysed the abstracts of nearly 800,000 articles published in psychology journals between 1970 and 2016. But the study also red flags a 24% increase during that period in an index for ‘clout’. This linguistic measure reflects language similar to “in my expert opinion,” that is confident and authoritative, perhaps in some cases too confident:

Although journal editors and reviewers should look out for exaggerated claims, they shouldn’t bear all the responsibility, Wheeler cautions. “It’s also up to universities and research institutes to value the quality over quantity of researchers’ outputs,” she says, “which would allow more time for academics to reflect and produce meaningful work instead of churning out as many publishable papers as possible.”

Wei adds a hedge of her own, however: The new study doesn’t show what caused the observed decline of hedging language. The pressure to publish that academics face to gain tenure, promotion, and professional recognition may play a role, but there could be other factors as well. The nature of the connection, she says, deserves further study.

Anonymous author