Hormonal Replacement Therapy in Cancer Survivors: Safety, Benefits, and Clinical Guidelines

Hormonal Replacement Therapy (HRT) in the oncologic context refers to the administration of exogenous sex hormones—primarily estrogens, progestins, or androgens—to alleviate symptoms caused by hormone deficiency following cancer treatment. Unlike endocrine therapy, which aims to block or suppress hormone signaling to treat hormone-sensitive malignancies such as breast or prostate cancer, HRT is used to restore hormonal balance in survivors experiencing vasomotor symptoms, genitourinary atrophy, osteoporosis, or reduced quality of life due to iatrogenic hypogonadism.

In oncology, HRT is most often considered for patients who undergo premature menopause after chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or surgical removal of gonadal tissue. While it can significantly improve quality of life, HRT use in cancer survivors—particularly those with hormone receptor–positive tumors—remains controversial due to concerns over cancer recurrence or progression.

This article explores the clinical dilemma of symptom relief versus oncologic risk, detailing the side effect profile of HRT in cancer patients, underlying biological mechanisms, recent evidence from clinical studies, and implications for personalized survivorship care.

Indications and Scope of Hormonal Replacement Therapy in Oncology

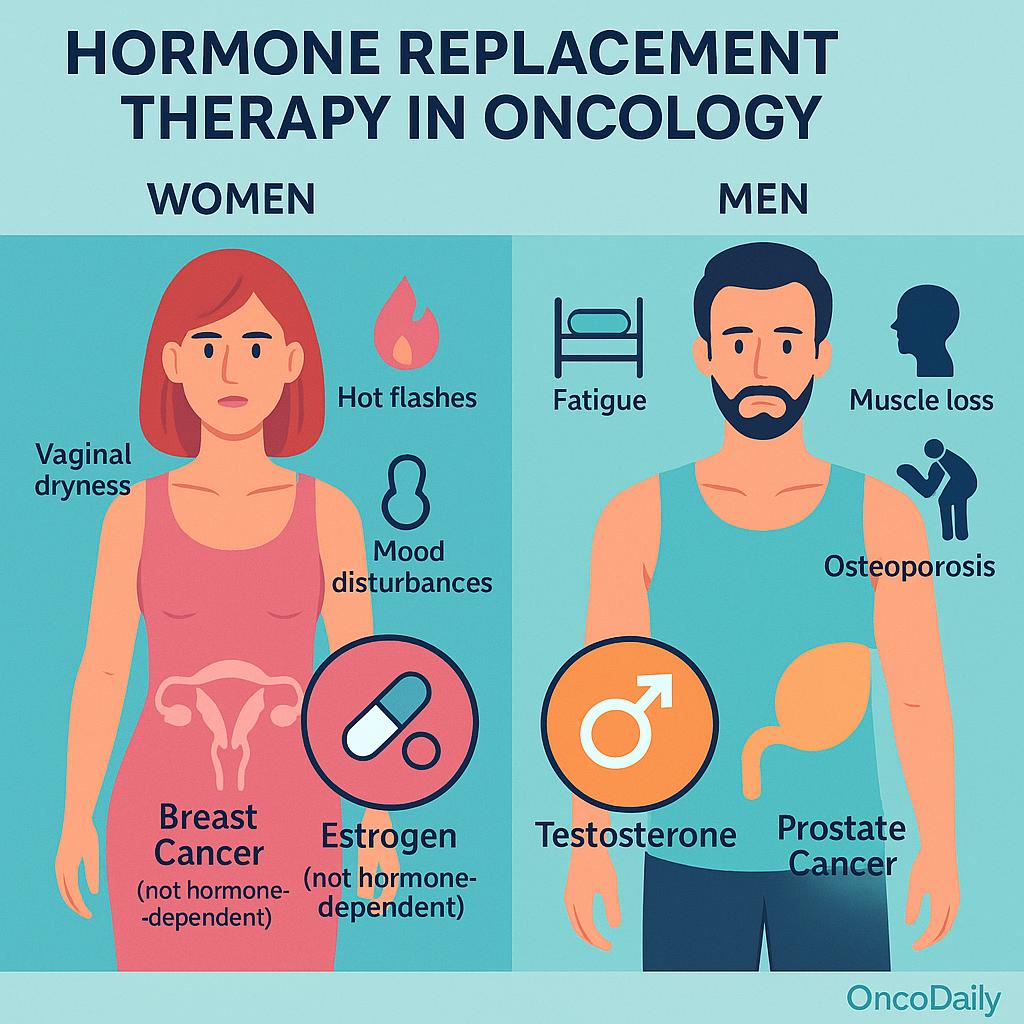

Hormonal Replacement Therapy (HRT) is considered in oncology primarily for the management of hormone deficiency symptoms that arise as a consequence of cancer treatment. These symptoms may include hot flashes, night sweats, vaginal dryness, sexual dysfunction, mood disturbances, and bone demineralization. In young breast cancer survivors, particularly those experiencing premature menopause following chemotherapy or oophorectomy, HRT may be considered to improve quality of life and mitigate long-term consequences of estrogen deficiency. Similarly, in men with prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), testosterone deficiency may result in fatigue, muscle loss, osteoporosis, and metabolic disturbances—raising the question of whether selected patients may benefit from testosterone replacement under careful supervision.

HRT is also relevant in survivors of hematologic malignancies, sarcomas, or gastrointestinal cancers who develop hypogonadism due to gonadotoxic chemotherapy or pelvic irradiation. In such cases, the decision to initiate HRT is typically guided by the patient’s age, symptom burden, reproductive goals, and risk profile. The use of HRT varies significantly between genders and cancer types. While women with non-hormone–dependent cancers may be candidates for systemic or local estrogen therapy, HRT is generally contraindicated in individuals with estrogen- or progesterone-receptor–positive breast cancer. Likewise, testosterone replacement in prostate cancer remains controversial, particularly in patients with a history of high-risk or metastatic disease.

Hormonal Agents, Mechanisms, and Formulation-Dependent Risks in Oncology HRT

The hormones commonly used in oncologic Hormonal Replacement Therapy (HRT) include estrogens, progestins, testosterone, and various combinations tailored to patient-specific needs. Estrogens are the primary agents used for managing menopausal symptoms in women and are available in multiple formulations, including oral tablets and transdermal patches or gels. Progestins are often added to estrogen therapy in women with an intact uterus to prevent endometrial hyperplasia. In male cancer survivors, particularly those affected by long-term androgen deprivation therapy, testosterone replacement may be considered to address symptoms of hypogonadism, such as fatigue, sexual dysfunction, and muscle loss.

These hormones exert their therapeutic effects by compensating for the decline in endogenous hormone levels caused by cancer treatments. Estrogens contribute to thermoregulation, alleviating vasomotor symptoms like hot flashes, while also supporting urogenital tissue integrity and maintaining bone mineral density. Progestins modulate endometrial proliferation, and testosterone restores anabolic and sexual functions in hypogonadal men.

The route of administration significantly influences the pharmacokinetic profile and safety of these agents. Oral estrogens undergo first-pass metabolism in the liver, leading to increased hepatic production of clotting factors, C-reactive protein, and triglycerides—factors associated with an elevated risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and cardiovascular events. In contrast, transdermal estrogens bypass hepatic metabolism and are associated with a more favorable cardiovascular and thrombotic risk profile.

Similarly, different progestins vary in their androgenic, anti-androgenic, and glucocorticoid activity, which can influence metabolic and vascular side effects. Testosterone formulations—including intramuscular injections, gels, and transdermal patches—also differ in their absorption patterns and associated risks.

Oncologic Safety and Tumor-Promoting Risks of Hormonal Replacement Therapy

The primary oncologic concern surrounding Hormonal Replacement Therapy (HRT) in cancer survivors is its potential to stimulate tumor growth or recurrence through hormone receptor–mediated mechanisms. In breast, endometrial, and prostate cancers—where tumor biology is often driven by estrogen or androgen signaling—exogenous hormone exposure may reactivate dormant cancer cells or accelerate proliferation of residual disease.

In estrogen receptor–positive (ER+) and/or progesterone receptor–positive (PR+) breast cancer, HRT raises particular concern due to the potential for estrogen to directly stimulate malignant cell growth. Several landmark studies have investigated this risk. The HABITS trial (Hormonal Replacement Therapy After Breast Cancer—Is It Safe?) reported a significantly increased risk of breast cancer recurrence in women receiving HRT (hazard ratio ~3.3), leading to early termination of the study. Similarly, the LIBERATE trial, which evaluated tibolone—a synthetic steroid with estrogenic and progestogenic properties—showed increased recurrence in breast cancer survivors, especially in ER+ cases. These findings reinforced the general guideline that systemic HRT is contraindicated in ER+/PR+ breast cancer survivors.

In contrast, patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), which lacks hormone receptor expression, may theoretically face a lower oncologic risk from HRT. However, due to limited long-term safety data, caution remains warranted even in this subgroup.

In endometrial cancer, unopposed estrogen therapy is associated with a known risk of recurrence or new primaries, particularly in patients with estrogen-driven type I tumors. The addition of progestins may mitigate this risk, but clinical decisions remain highly individualized and influenced by histologic subtype and stage.

In prostate cancer, HRT considerations usually relate to testosterone replacement in men previously treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Traditionally, testosterone has been considered contraindicated in prostate cancer due to its role in tumor proliferation via the androgen receptor (AR). However, emerging evidence suggests a more nuanced risk profile. In men with low or intermediate-risk localized prostate cancer, some studies have reported no significant increase in recurrence with carefully monitored testosterone therapy. Conversely, in high-risk or metastatic disease, AR stimulation remains a major concern, and testosterone replacement is generally avoided.

Molecularly, tumor-promoting effects of HRT are linked to reactivation of hormone receptor pathways, ligand-induced receptor dimerization, and downstream activation of proliferative signaling cascades such as PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK. Additionally, hormonal exposure may promote epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and angiogenesis, potentially facilitating metastasis in hormone-sensitive malignancies.

Systemic Adverse Effects of Hormonal Replacement Therapy in Cancer Survivors

Hormonal Replacement Therapy (HRT), while often effective in alleviating hypogonadism-related symptoms, carries a distinct profile of systemic adverse effects that must be carefully considered in cancer survivors. Cardiovascular complications are among the most well-established risks, particularly with oral estrogen formulations. These include an increased incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE), stroke, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease—risks that are accentuated in older patients and those with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions. Transdermal estrogen, by avoiding first-pass hepatic metabolism, is associated with a more favorable cardiovascular profile. In men receiving testosterone therapy after androgen deprivation, alterations in lipid profiles—such as reductions in HDL and increases in LDL—may further contribute to cardiovascular risk and warrant close lipid monitoring.

HRT may also lead to breast and gynecologic complications. Women often report breast tenderness and increased glandular breast density, which can complicate mammographic surveillance and potentially mask early malignancies. Estrogen stimulation of the endometrium in women with an intact uterus can lead to abnormal uterine bleeding and, over time, endometrial hyperplasia. The addition of a progestin is essential in these patients to reduce the risk of endometrial neoplasia, while women with prior hysterectomy may avoid this complication and typically require estrogen alone.

Metabolic disturbances are another important consideration. HRT has been associated with changes in glucose metabolism, including the potential for insulin resistance, as well as weight gain and shifts in lipid profiles. These effects can be especially problematic in cancer survivors who may already have metabolic dysregulation due to steroid therapy, physical inactivity, or underlying malignancy-related cachexia or sarcopenia. The cumulative burden may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes in the long term.

Neurologic and cognitive effects of HRT remain an area of active investigation and debate. Some studies suggest a neuroprotective role for estrogen, particularly in younger postmenopausal women, with possible benefits on memory, attention, and verbal fluency. However, large trials such as the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study have linked HRT in older women to an increased risk of dementia and cognitive decline. Beyond cognition, HRT may influence sleep patterns, mood, and psychological well-being—effects that vary significantly depending on treatment duration, individual susceptibility, and pre-existing neuropsychiatric conditions. Differences in clinical outcomes between short-term symptom management and prolonged hormone exposure further underscore the need for personalized treatment planning.

Special Considerations in Breast and Prostate Cancer Survivors

Hormonal Replacement Therapy (HRT) in cancer survivors requires particularly nuanced evaluation in individuals with a history of hormone-sensitive malignancies, such as breast and prostate cancer. In breast cancer survivors, especially those with estrogen receptor–positive (ER+) tumors, systemic HRT is generally contraindicated due to the well-documented risk of recurrence. Estrogen can directly stimulate residual cancer cells via the ER pathway, posing a significant oncologic hazard.

However, survivors often face severe menopausal symptoms—including hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and sexual dysfunction—that negatively impact quality of life. In such cases, local (vaginal) estrogen therapies have been explored as a safer alternative for urogenital symptoms. While systemic absorption of low-dose vaginal estrogen is minimal, safety concerns remain, particularly in patients receiving aromatase inhibitors. Some guidelines cautiously permit local estrogen in highly symptomatic patients after other treatments—such as vaginal moisturizers, lubricants, or non-hormonal pharmacotherapy—have failed, but decisions should be individualized and made in collaboration with the oncology team.

In prostate cancer survivors, the use of testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) after androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) remains a subject of ongoing debate. ADT is a mainstay in the treatment of advanced or high-risk prostate cancer, but prolonged testosterone suppression leads to significant side effects, including fatigue, loss of libido, decreased bone density, and metabolic syndrome. For men with low- or intermediate-risk localized disease who have been in remission for an extended period, emerging observational data suggest that TRT may not significantly increase the risk of recurrence if closely monitored.

However, in patients with high-risk, recurrent, or metastatic disease, testosterone remains a potential driver of tumor growth through androgen receptor activation, and replacement is typically avoided. The concept of a “saturation model”—whereby prostate cancer cells do not respond to further increases in testosterone beyond a certain threshold—has been proposed to explain the safety of TRT in select cases, though it remains controversial and unproven in randomized trials.

Survivorship care guidelines emphasize shared decision-making in these complex scenarios. Organizations such as ASCO, NCCN, and ESMO recommend a case-by-case approach that incorporates tumor characteristics, time since diagnosis, treatment history, symptom severity, and patient preferences. Regular monitoring, including hormonal levels, imaging, and tumor markers where appropriate, is essential if HRT is initiated. Equally important is patient educationabout the benefits and risks of HRT, along with the availability of non-hormonal alternatives that may offer partial symptom relief without oncologic risk.

Alternatives and Risk-Adapted Strategies for Symptom Management in Cancer Survivors

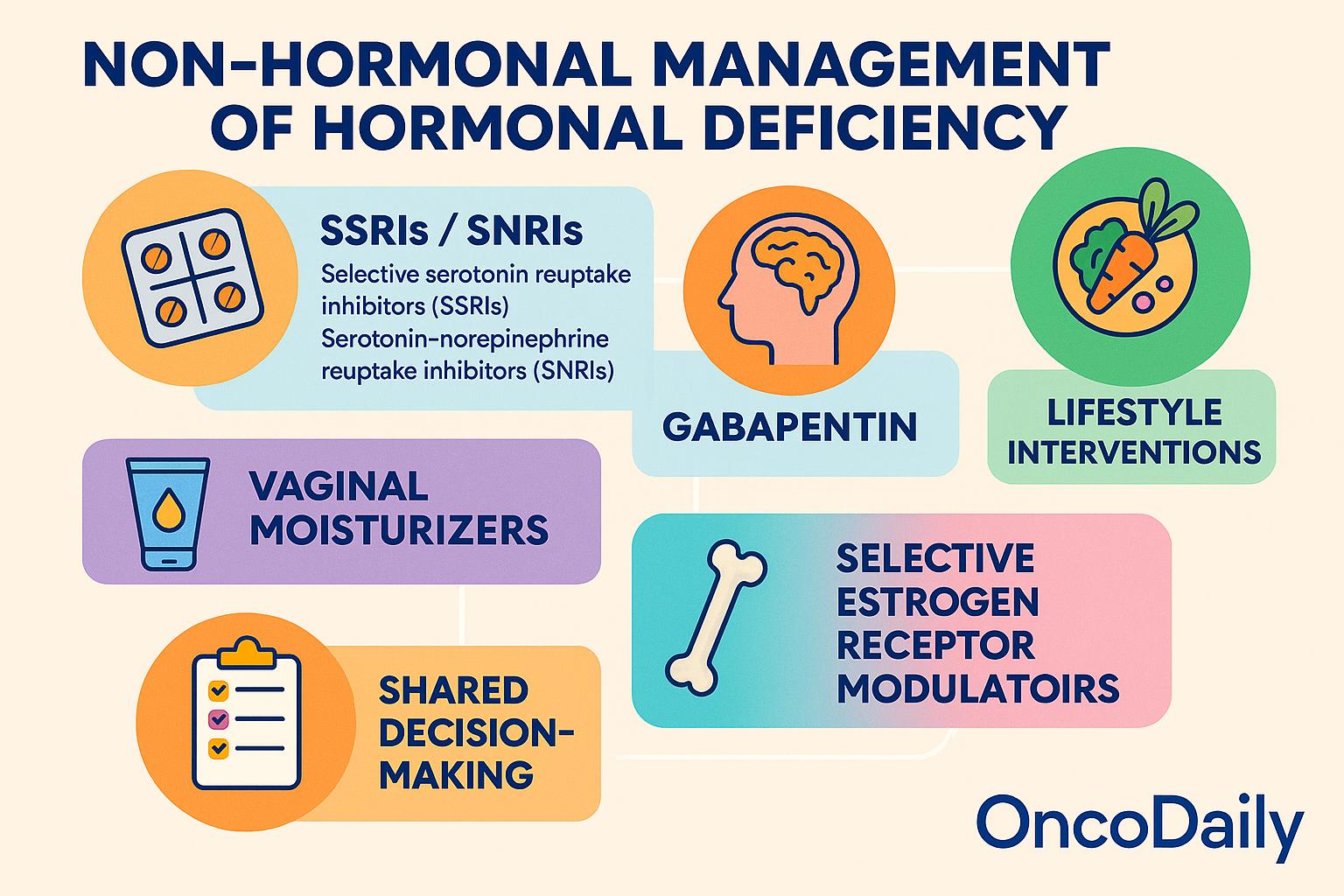

For cancer survivors in whom Hormonal Replacement Therapy (HRT) is contraindicated or deemed too risky, several non-hormonal alternatives have demonstrated efficacy in managing symptoms of hormonal deficiency. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as venlafaxine and paroxetine, have been shown to reduce the frequency and severity of hot flashes by modulating central thermoregulatory pathways.

These agents are particularly useful in women with hormone-sensitive breast cancer, although care must be taken to avoid cytochrome P450 (CYP2D6) interactions in patients receiving tamoxifen, as some SSRIs may reduce its efficacy. Gabapentin, traditionally used as an anticonvulsant, has also demonstrated benefit in reducing vasomotor symptoms, particularly nocturnal hot flashes, and may be a viable option when SSRIs/SNRIs are poorly tolerated.

For urogenital symptoms such as vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, vaginal moisturizers and lubricants provide symptomatic relief without the risks associated with systemic estrogen exposure. In cases of severe bone loss or high fracture risk, bisphosphonates or denosumab may be used to preserve bone mineral density and reduce skeletal complications in patients unable to receive estrogen-based bone protection.

Lifestyle interventions, including dietary modifications, regular physical activity, weight management, and smoking cessation, have shown promise in alleviating vasomotor symptoms and improving metabolic outcomes. Exercise, in particular, has been associated with reduced frequency and severity of hot flashes, improved mood, and enhanced overall well-being. Nutritional support, including vitamin D and calcium supplementation, is also important for maintaining bone health, especially in the context of premature menopause or androgen deprivation.

Pharmacologic alternatives that modulate estrogen pathways without systemic hormone exposure offer additional options. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as ospemifene and raloxifene, exert tissue-specific estrogenic and anti-estrogenic effects and may be useful in managing vaginal atrophy or bone loss without stimulating breast tissue. Similarly, tissue-selective estrogen complexes (TSECs), which combine SERMs with low-dose estrogens, are under investigation for their ability to relieve menopausal symptoms while minimizing endometrial and breast proliferation, though their role in oncology remains limited and investigational.

Ultimately, the choice of therapy requires shared decision-making, integrating clinical judgment with patient values and preferences. Risk stratification tools, such as recurrence risk calculators and comorbidity indices, can aid in determining the appropriateness of various therapies. In some cases, genomic assays (e.g., Oncotype DX, Prolaris) may provide insights into tumor biology and inform the safety of interventions, especially when considering borderline HRT eligibility in hormone-sensitive disease.

Guideline Recommendations and Risk-Benefit Frameworks for HRT Use in Cancer Survivors

Major clinical organizations—including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), and North American Menopause Society (NAMS)—generally advise against the routine use of systemic Hormonal Replacement Therapy (HRT) in survivors of hormone-sensitive cancers, particularly estrogen receptor–positive (ER+) breast cancer and advanced prostate cancer. These guidelines consistently emphasize that the decision to initiate HRT must be individualized and guided by a thorough understanding of the patient’s cancer type, hormone receptor status, symptom severity, and risk of recurrence.

According to NCCN and ASCO, systemic HRT is contraindicated in women with ER+/PR+ breast cancer, while transdermal or vaginal low-dose estrogen may be considered with caution in cases of refractory urogenital symptoms after failure of non-hormonal options, and only with oncologist approval. For prostate cancer survivors, ESMO and ASCO note that testosterone replacement may be cautiously considered in low-risk, long-term survivors who are free from disease recurrence, but it remains discouraged in those with high-risk or metastatic disease.

All major guidelines emphasize a risk-benefit approach when considering HRT in cancer survivors. This begins with a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s cancer history, recurrence risk, age, comorbidities, and symptom severity. Non-hormonal alternatives—both pharmacologic and lifestyle-based—should be discussed, and any decision to proceed with HRT must involve informed consent outlining potential oncologic and systemic risks. A multidisciplinary team, including oncologists, endocrinologists, and survivorship specialists, is essential for guiding individualized care.

When HRT is deemed appropriate, guidelines recommend using the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible duration, with a preference for non-oral routes such as transdermal formulations to reduce thrombotic and metabolic complications. Therapy should be reassessed every 6 to 12 months. Surveillance protocols include regular clinical follow-up, monitoring for hormone-related side effects, and appropriate imaging or lab testing based on the patient’s cancer type. Across all recommendations, patient-centered decision-making remains central—aiming to enhance quality of life without compromising oncologic safety.

Future Directions in Hormonal Replacement Therapy for Cancer Survivors

As the landscape of survivorship care evolves, research into safer and more personalized approaches to Hormonal Replacement Therapy (HRT) continues to expand. Ongoing clinical trials are investigating the safety of low-dose HRTregimens and novel delivery systems, such as intravaginal rings and microdosed transdermal formulations, aiming to minimize systemic exposure while preserving symptom control.

Advances in precision medicine are introducing the potential for pharmacogenomic profiling and biomarker-guided therapy, allowing clinicians to identify patients who may metabolize hormones differently or have varying levels of receptor sensitivity—thus enabling more tailored and safer use of HRT.

There is also a growing recognition of the need for long-term, prospective studies in cancer survivors, particularly those diagnosed at a young age, who may face decades of hormone deficiency and unique survivorship challenges. Current data remain limited in this population, and long-term safety outcomes are poorly understood.

Importantly, there is an urgent call for greater inclusion of diverse patient populations in HRT research, including transgender individuals who may require lifelong gender-affirming hormone therapy following a cancer diagnosis. Understanding the intersection of oncology and gender-affirming care is critical to ensuring equitable, evidence-based treatment for all survivors.

You Can Watch More on OncoDaily Youtube TV

FAQ

What is hormonal replacement therapy in cancer survivors?

HRT restores hormones lost due to cancer treatment, aiming to relieve menopause or hypogonadism symptoms.

Is HRT safe for breast cancer survivors?

Systemic HRT is generally contraindicated, especially in ER+ breast cancer, due to increased recurrence risk.

Can men with prostate cancer receive testosterone therapy?

In select low-risk cases, carefully monitored TRT may be considered, but it’s avoided in high-risk or metastatic disease.

What are safer alternatives to HRT for cancer survivors?

SSRIs, SNRIs, gabapentin, vaginal moisturizers, and bisphosphonates are commonly used non-hormonal options.

What are the risks of HRT after cancer?

HRT may increase the risk of cancer recurrence, cardiovascular events, thrombosis, and endometrial hyperplasia.

How is HRT administered safely in survivors?

Transdermal forms are preferred over oral; lowest effective dose is used with ongoing surveillance.

What do ASCO/NCCN guidelines say about HRT in cancer patients?

They recommend an individualized risk-benefit approach and discourage systemic HRT in hormone-sensitive cancers.

Can vaginal estrogen be used in breast cancer survivors?

Possibly, under oncologist supervision and after failure of non-hormonal treatments, especially for urogenital symptoms.

Are there newer options for safe HRT delivery?

Yes, microdosed transdermal patches and vaginal rings are under investigation to minimize systemic hormone exposure.

-

Challenging the Status Quo in Colorectal Cancer 2024

December 6-8, 2024

-

ESMO 2024 Congress

September 13-17, 2024

-

ASCO Annual Meeting

May 30 - June 4, 2024

-

Yvonne Award 2024

May 31, 2024

-

OncoThon 2024, Online

Feb. 15, 2024

-

Global Summit on War & Cancer 2023, Online

Dec. 14-16, 2023