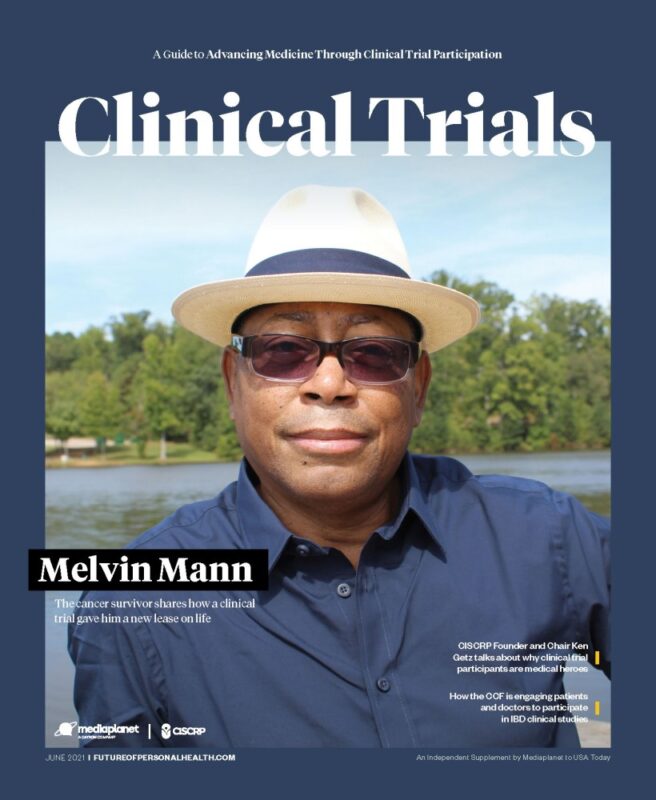

Mel Mann, Patient Advocate at Health Equity, Clinical Trials, Marrow Donation, shared on LinkedIn:

“The Mel Mann Story: From Terminal Cancer to 30-Year Survivor (January 1995 – Jan 2025)

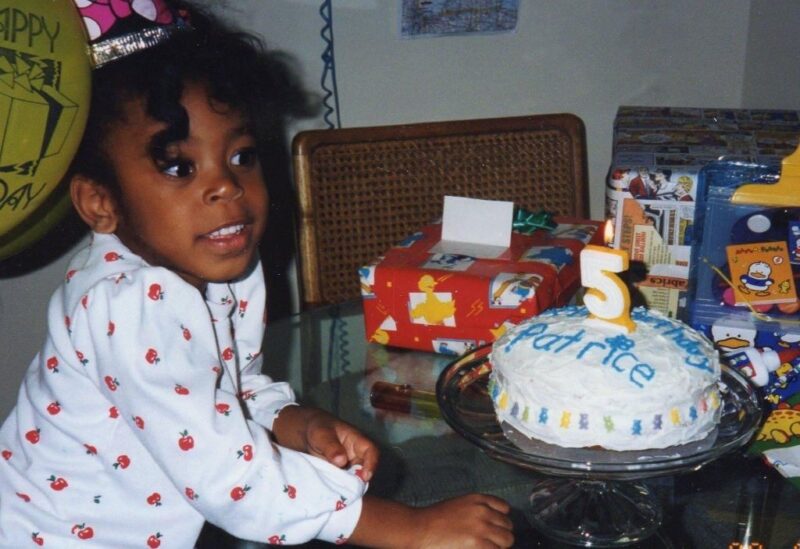

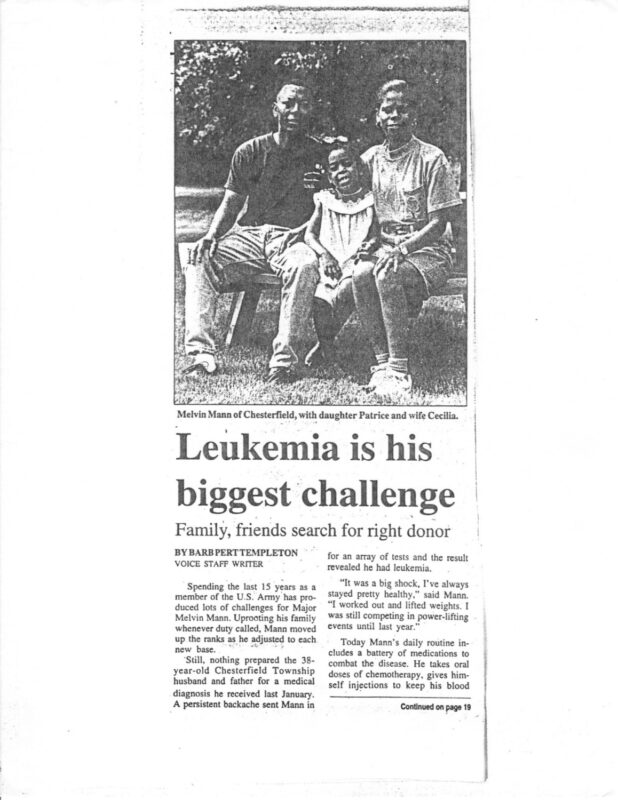

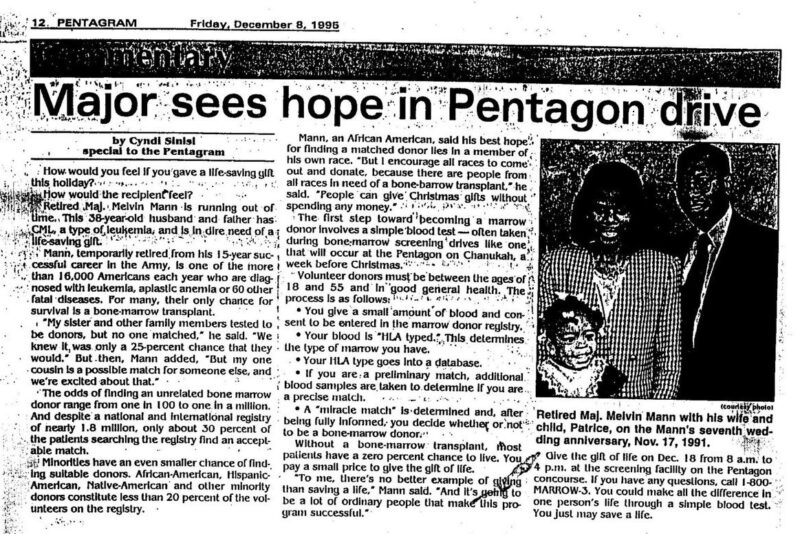

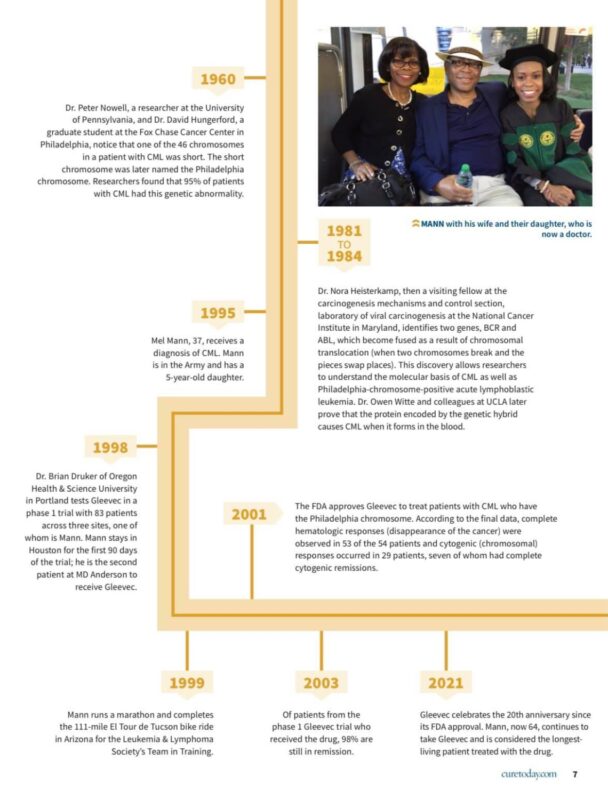

My cancer journey began over 30 years ago, in December 1994. I was a 37-year-old Army major, stationed in Detroit Michigan, with my wife, Cecelia, and our five-year-old daughter, Patrice.

I worked in Research and Development for Infantry weapon systems since I was commissioned into the Infantry. On this particular assignment, I was the Bradley Fighting Vehicle fielding officer. I enjoyed this job because it called for me to travel to all of the many places in the world where they had the Bradley, such as Germany, Korea, or places like Montana, Oregon, Mississippi, etc., and give briefings on the Bradley Fighting Vehicle.

I had this pain in my back that would not go away and some fatigue. This had been going on for about a year and became increasingly worse. I had tried pills, traction, and physical therapy, but found no relief, so the doctor at the local military clinic ordered an MRI. Not every military base has a major medical facility or the ability to perform major tests such as an MRI. I had to drive three hours from Detroit to the Wright Patterson Air Force Base Medical Facility in Dayton Ohio, to take the MRI. The MRI machine is like a long chamber that slides you into, and it scans your entire body. The machine looked like a coffin to me.

The technician told me to lie still, which was hard to do because of the back pain, and he offered me a choice of music to listen to. I chose this CD by Toni Braxton. That turned out to be a bad choice of music because the CD had a song on it called ‘Breathe Again.’

So I lay in this coffin-like machine, listening to the lyrics, which went something like this, I promise you that I shall never breathe again. That I shall never breathe again. I’ll never feel you in my arms again. I’ll never feel your tender kiss again, never hear you say ‘I love you’.

Now, this was real. At the same time, the technician kept telling me to lie still. I kept fidgeting, thinking that I was lying here in this tube because I couldn’t lie still. I yelled back at him, that he needed to change that music. I remember sitting in my boss’s office the next week laughing about how eerie the MRI procedure was like the whole experience was some type of foreshadowing.

The next month, January 1995, on a wintry Michigan morning, I casually sauntered into the Air Force clinic on my way to work to pick up the MRI results. This was a small clinic on a military post. I did not make an appointment but just walked in.

The doctor looked a bit surprised. I asked about the MRI. She took me back to her office. This was before computerized medical records. She looked through her stack of papers and found the MRI report. She started reading the report, and as she read it, I could see her expression change. She told me to have a seat. Strangely, the chairs in her office were like kitchen bar stools. I was too worried to ask her why she had these bar stools in her office.

She called in her technician to give me a simple blood test called a CBC. Meanwhile, the doctor told me, ‘The MRI report says that you have a herniated disk and also that your bone marrow is not normal for someone your age and that you may have leukemia’. She added as she stood, and I sat on the bar stool looking at her -eye to eye, ‘But don’t worry, leukemia is very curable, like about 80-90 percent.’

Meanwhile, the technician came back in and said my white blood count was 140,000. I didn’t know what 140,000 meant, but I knew from the way he emphasized it, that it wasn’t good. Normal white blood count is under 10,000.

The Doctor then said, ‘I’m a general practitioner. I need to call the hematologist-oncologist at Wright Patterson Air Force Base.’ She steps out of the office for a few minutes. When she came back in she said, ‘The oncologist wants you to drive to Wright Patterson today and be prepared to stay 3 days or 30 days. He has to take some more tests to see what kind of leukemia you have.’ I felt like I was about to fall off that bar stool.

I decided to go back home before going to work. I sat down on the couch. I must have had a strange look on my face because my wife looked at me and asked, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ I told her what happened. As she entered into a state of shock, she sat beside me, and tears rolled down her face.

I still had to go to work, to tell my boss, because I could not just disappear for 30 days or even three days in the Army. I sat down on the couch in his office. He looked at me and said, ‘What’s wrong with you?’

I said, ‘You know that MRI we were laughing about?’

I drove down to Wright Patterson later that evening. The next afternoon, I went to the oncologist’s office. There was only one other patient in the waiting room. He was a young soldier from Fort Knox Kentucky, who had just been diagnosed with leukemia a month earlier. So I started asking him questions, because back then the internet was a rare thing. Most people did not even have personal computers to google their disease.

Asking this soldier questions turned out to be a bad Idea. He started talking about the needle they used to do the bone marrow biopsy and aspiration and how big the needle was. He talked about the needle for about 20 minutes. His descriptive recount of the procedure told me this was going to be a long day. He talked about it so much that when I met the doctor, I asked if I could see the needle because the doctor was the one who did the marrow biopsies and aspirations. It was the biggest needle I had ever seen.

The doctor asked me if I wanted to take any medication to sedate me as some of the other patients did. I said, ‘No’. As he was doing the procedure, I decided this would be a good time to meditate, even if I never meditated before, because I figured this procedure was going to hurt. In my mind, I went out to the beach and played a mental game of chess to escape the pain.

After the biopsy, aspiration, and some blood tests were completed, the doctor invited me to sit on the couch in his office. He then said, ‘I think I know what you have, but I will have to wait a couple of weeks for the test results to come back in. Looks like you have chronic myelogenous leukemia (chronic myeloid leukemia), CML for short. The prognosis is a three-year life expectancy. That’s the average, it could be more and it could be less.’

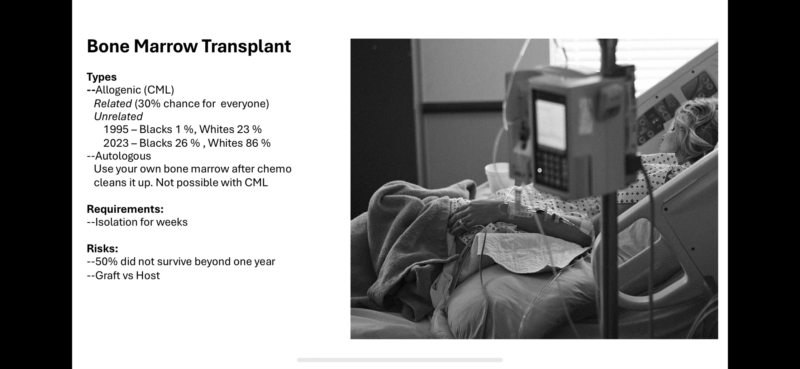

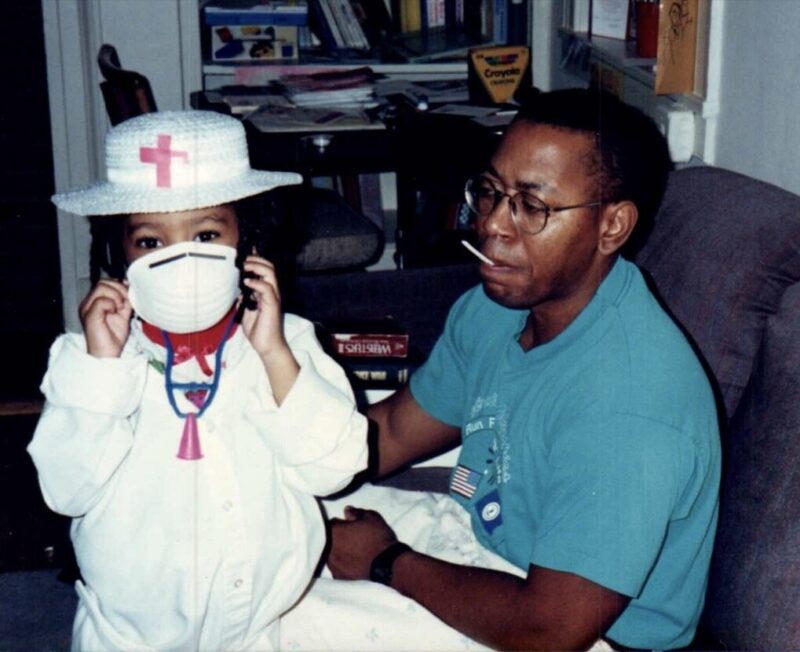

He further explained, that with a bone marrow transplant, I had a 50/50 chance of a cure, but my body could reject the donor’s marrow, and I could die from the procedure, because of something called ‘graft versus host’. Some people chose not even to look for a donor because of the high mortality rate at the time, of rejecting the donor’s marrow. Better three years than six months, they reasoned. I knew I had to go for the marrow transplant because I had a five-year-old daughter and I wanted to be around long term for her. I asked the doctor why no one called me to come in earlier. He responded, ‘I guess they didn’t want to spoil your holidays’.

5 year-old Patrice

At this point, I felt like I was underwater, sinking further down into the couch, as I listened to the doctor’s voice, which floated towards me in sluggish and muffled waves. I told this doctor that the doctor at my base said leukemia had a good cure rate. He said, ‘That’s for childhood leukemia, but not for what you have’. Coincidentally, I heard a thumping noise drumming in the background. I glanced to the side and realized the drumming sound was the secondhand ticking on the wall clock. My world had changed in a matter of seconds.

The last time I heard a clock ticking like that was about 16 years earlier. I was in Army ROTC, at Xavier University in Cincinnati Ohio, and during the summer break between junior and senior year of college, I decided to go to Airborne School at Fort Benning, in Columbus Georgia, and learn how to jump out of airplanes. The first time I had been on a plane was flying down to Airborne School. The second time was two weeks later as I was getting ready to jump out of a plane.

Despite all the intensive paratrooper training I had received for over two weeks, as I was on the plane, in the air, heading towards the jump zone, the flight crew announced we had six minutes before we were to jump out of the plane to make our first of five daily jumps, I started to feel a little bit apprehensive. I heard a ticking sound, looked down at my watch, and could have sworn I heard my watch ticking.

Army ROTC 1979 after Airborne School

The doctor, continued, ‘Do you have a sibling?’

I responded that I had one sister, somehow feeling that was not the right response. He continued, ‘She’s your best chance of finding a marrow match since you get half of your DNA from your father and the other half from your mother. If a relative doesn’t match, you will have to look on the national registry for an unrelated marrow donor. To be a match, a donor must share the same ethnicity as the recipient.’

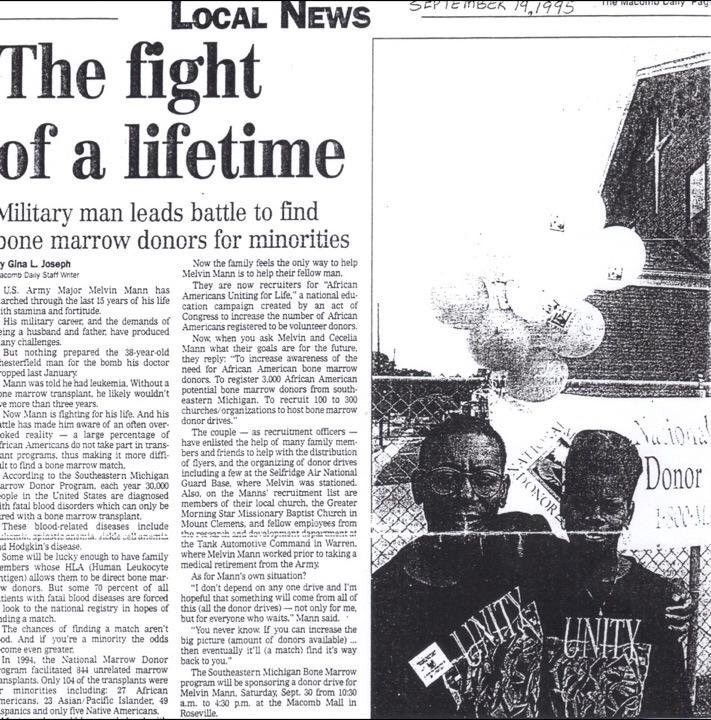

The doctor stated, ‘Currently, there are very few African Americans on the marrow donor registry,’ He continued, ‘Last year, in 1994, 2000 African Americans needed transplants, only twenty of them found lifesaving donors’. This was a real-life introduction to health disparities and the social determinants of health.

I asked the doctor if diet and exercise could help. He said no. I asked him if I could still exercise. In an attempt to ease my anxiety, he replied, ‘Yes, but don’t run any marathons’ Then the doctor added, ‘You’ll be okay because you can take a lot of pain’. Then he said, ‘It could be worse’ and named a few other aggressive cancers. I didn’t like the part about pain or knowing there were worse illnesses. I would eventually have over 50 of those ‘painful’ bone marrow aspirations in the coming years. One time I had three in one day, from each of my hips and my chest bone.

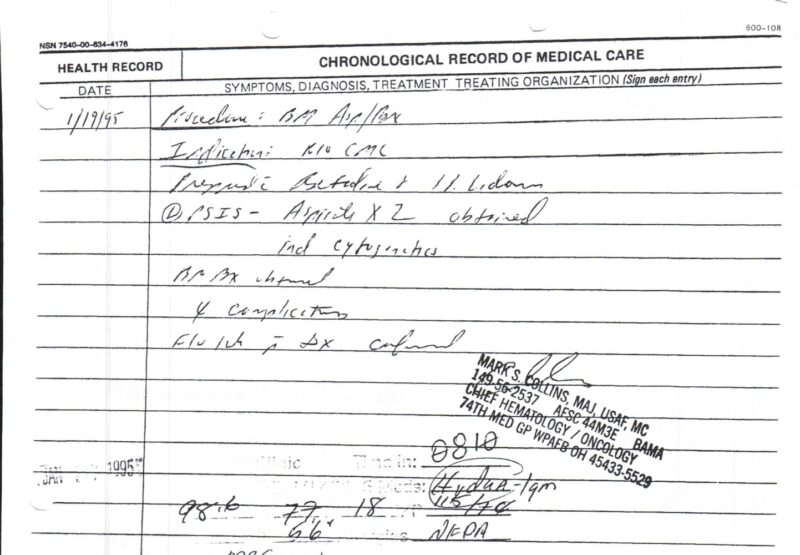

The official date of CML Diagnosis — January 19, 1995, Wright Patterson Air Force Base

Thoughts of my five-year-old daughter raced through my mind. After counting and re-counting, I concluded, that in three years, daddy’s little girl would only be eight years old. She still had one training wheel on her little pink bike that she got for Christmas, and my wife and I were teaching her how to ride it.

Blindsided by this diagnosis, I wondered if I would make it to my 40th birthday.

As I left the doctor’s office, somehow I did not feel the back pain anymore. Cars were still going up and down the street as usual, and there I stood like a deer caught in the headlights of an incurable diagnosis. I felt like I had a losing lottery ticket, but I needed to recheck the numbers because my luck couldn’t be this bad.

I agonized over how I was going to break this news to my mother. My only brother had passed a few years earlier, so I knew this would be hard on my mother. My mother did not like going to the doctor. She would always say, ‘You go in there for one thing, you come out with something else’. We drove down to Cincinnati to tell my mom and sister in person. I sat down on the couch. My mom looked at me, and guess what she said? Yes, she said, ‘What’s wrong with you’.

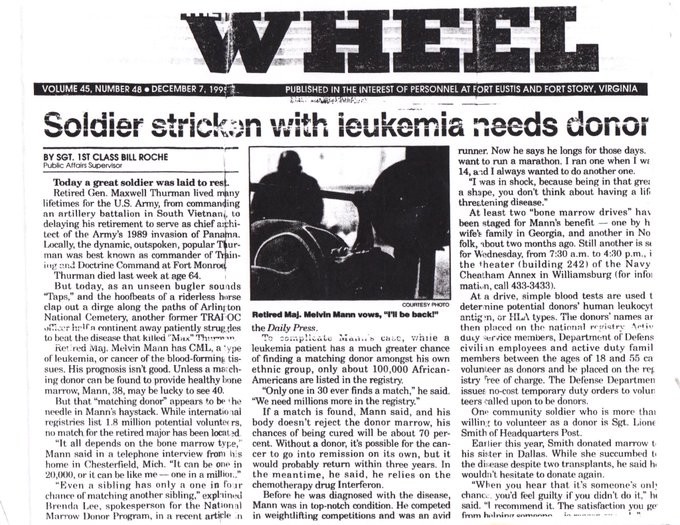

Unwilling to accept the diagnosis, I asked the Army to fly me to the Walter Reed Medical Center, in Bethesda, Maryland, for a second opinion. In my state of denial, I was seeking someone to dispute this diagnosis; unfortunately, Walter Reed confirmed the diagnosis. I flew over to the Cancer Treatment Center in Chicago. I then went to three local doctors. All the doctors chanted the same thing – three years to live, three years to live, three years to live unless a bone marrow donor could be found.

The Walter Reed doctor’s opinion initiated the paperwork for my temporary medical retirement from the military. I was told the military did not perform marrow transplants on active-duty personnel. I would have to be discharged from the military. If I found a marrow donor, according to Walter Reed, I would have to go to the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, in Seattle Washington, to have the marrow transplant performed. Further, if I recovered sufficiently enough within a certain time limit, then I could come back on active duty. The Walter Reed doctor wrote in his notes to the doctor back at Wright Patterson, ‘Thanks for sending me this interesting case’. I then flew back home and started CML treatment — daily injections of interferon until I could find a bone marrow match.

Things continued to spiral downward. My first disappointment came when no marrow matches were found among my relatives. Further, no one on the national marrow registry matched me.

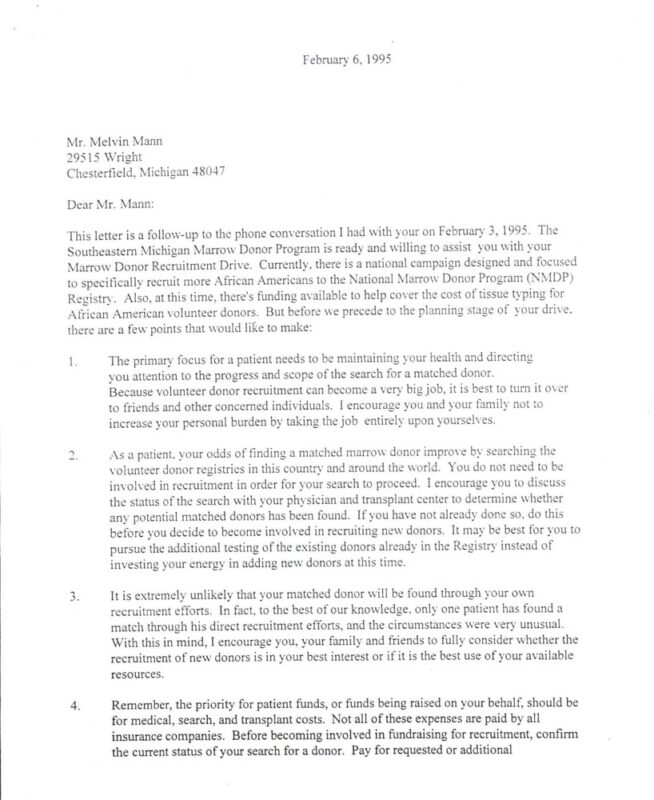

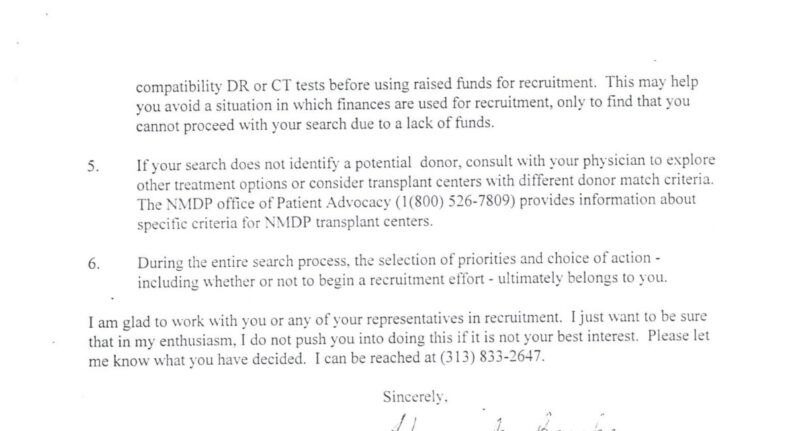

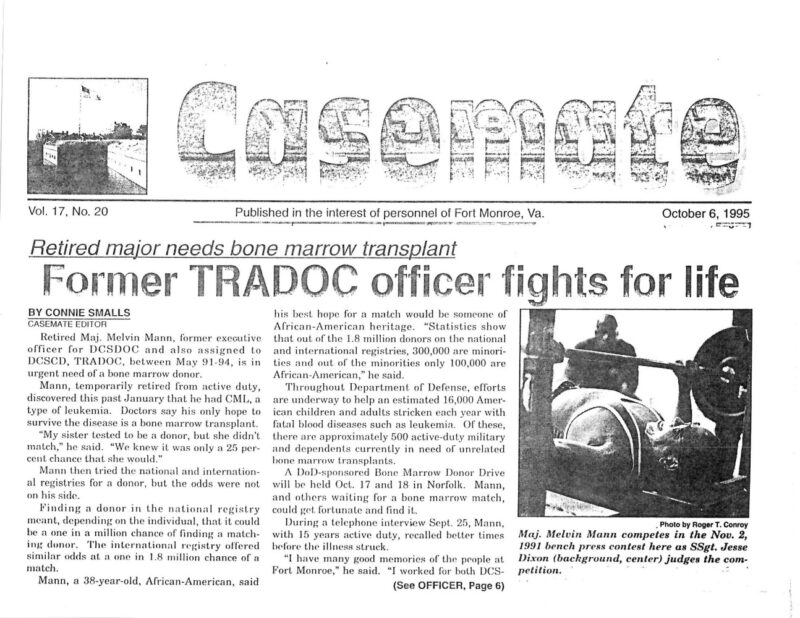

I contacted the Marrow Donor Organizations to tell them I wanted to start doing marrow drives. I received a letter stating that no one had ever found their unrelated marrow donor and the letter suggested I should spend my time adjusting to the medical treatments, but if I wanted to proceed, they would be happy to work with me. While in Bethesda, I stopped by the Department of Defense (DOD) Marrow Foundation, to enlist their aid in setting up marrow drives within the military.

Red Cross letter informing me that no one finds their donor.

Although I would have preferred to have fought this battle quietly with conventional chemotherapy and radiation, I did not have the option of digging in and beating cancer through my willpower. I would have to rely on the benevolence of a stranger that I had not met, and who probably had never heard of marrow transplantation.

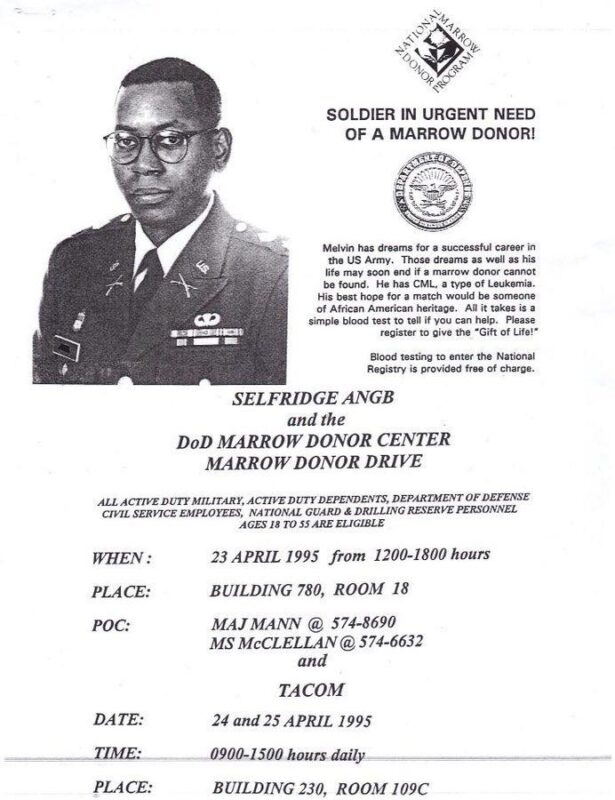

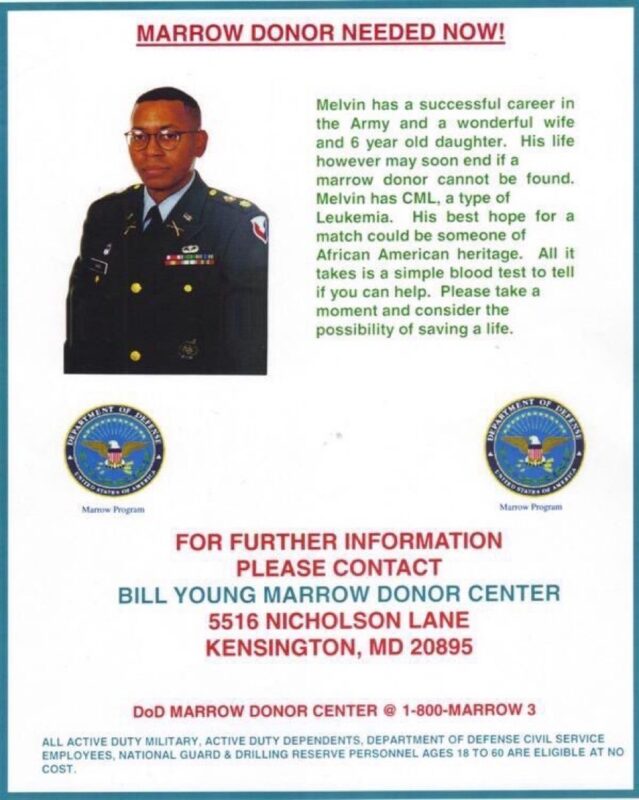

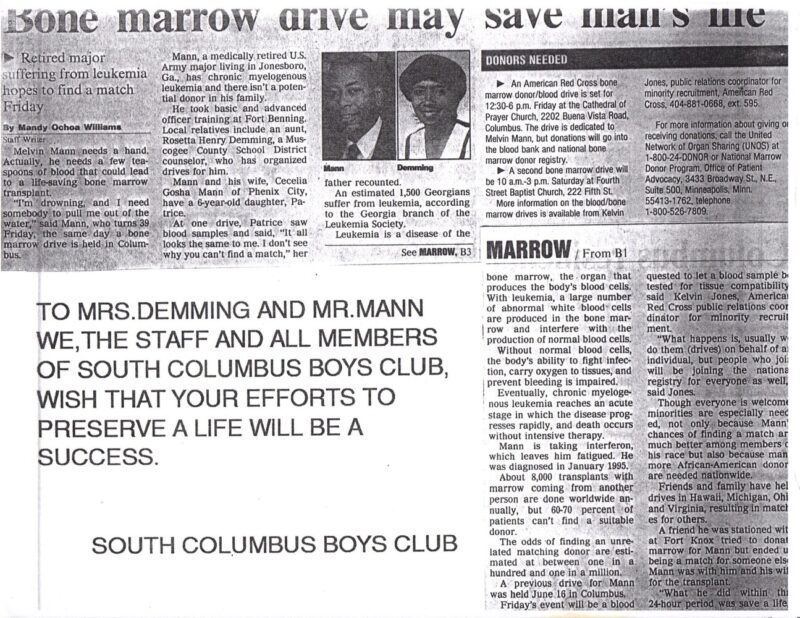

I sensed that my situation meant I was being called into the marrow recruitment arena as a spokesperson and educator. I didn’t think my chances would be very good at finding a donor if I didn’t get personally involved. I had three years to live. It was short, but I thought it was long enough to put up a good fight. I did have some skills which came in handy as the Army had trained me earlier in public affairs and I had served 30 months as a recruiting company commander. I also have a degree in public relations. For starters, the marrow organizations ended up putting my face on posters. A poster is the last place you want your face on, for any reason.

I went up through the chain of command and told them what I wanted to do and they supported me. You can’t have marrow drives on military posts without the approval of each post’s commanding officer. And then you had to get volunteers to help out, recruit phlebotomists to draw blood, and so forth. You could only go as fast as the volunteer phlebotomists could draw the blood, so the drives would take a long time.

Click to see the 1995 Promotional Marrow Drive video for the above Marrow Drive.

For the marrow drives, I lent my face and my time to these marrow donor organizations. They, along with my friends and family started hosting marrow drives. At the first drive, which my co-workers helped organize, 342 people, including the doctor with the bar stools who first diagnosed me, gave blood samples. These people all join voluntarily. You can’t make anyone join the marrow registry.

I remember one co-worker in the office named Jimmy, passed out at the marrow drive because he was afraid of needles. The folks at work teased him unmercifully for weeks about that. He sat a couple of desks down from me and would ask interesting questions about how he was coping with a terminal diagnosis. A lady from a different part of the post came by my desk. She said she was running a marathon and raising money for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society’s (LLS) Team in Training. She had a clipboard where she was writing down the names and donations. At the top of the clipboard, there was the slogan ‘Cure2000.’

I asked her what that meant and she replied, ‘Oh, we’re going to cure leukemia by the year 2000’. I added my 3-year life expectancy to 1995 and came up with 1998, which was two years too short. I thanked her for her efforts and gave her a donation.

We did drives everywhere — college campuses, military bases, malls, and churches, among other places. My daughter, at one of the drives, exclaimed, ‘Daddy, I can’t see why you can’t find a match. All the blood looks the same to me.’

Click to see Live Video from a Bone Marrow Drive at a Mall.

While very few in the community had heard about bone marrow transplants, they gave me overwhelming support. I would look out the window and see a neighbor’s teenage son cutting my grass, people would bring us home-cooked meals, and a local chiropractor, whose grandmother had recently passed from cancer, told me to come in as often as I wanted to fix my back.

High school girls in the on-post housing volunteered to babysit Patrice and would man the refreshments table at the marrow drives. Videos educating military personnel, employees, and dependents about marrow donation and my drives ran on the post television station around the clock. I also had friends who did marrow drives for me in places like Hawaii, Germany, and even the Pentagon.

I got encouraging phone calls like this one from a friend at Fort Eustis, Virginia, who said, ‘Five hundred of us are marching down to the post theater to see if we can be a match for you’. Friends would pass through when they were on leave or changing duty stations and say, ‘I saw your poster in Germany.’

One of the Generic posters was sent to all the military bases around the world.

I remember I wanted to do a bone marrow drive at a particular mega-church that had thousands of members. The Marrow Donor Representative asked me, ‘Are you sure you want to do a drive at this church? They had a bone marrow drive for two little girls with leukemia, and only two people showed up for the drive’. Now, I did pause for a second, but I said, ‘Yes, I want to have a bone marrow drive there, I’m just planting seeds’.

One evening, I had a special meeting with about 100 men from the church to educate them about the marrow donor process. They asked questions like what happens with my DNA?

Can I volunteer just for you?

Later, at the actual drive, we had about two hundred people sign up to be potential bone marrow donors.

I always educated people about the marrow donation process before they joined the registry. One important thing, I always mentioned is they may not be my match, but if they matched someone else, I still needed them to go through with the marrow donation. In turn, I felt other cancer patients were doing the same things at their drives. I had seen patients find matches, the potential donor back out, and the patient died because no other match could be found.

Recruiting marrow donors is not easy. Most people only get about 5 to 10 percent of the people they ask, if that much. On rare occasions, I got up to fifty. I remember talking to a group of people and half of the group volunteered. My experience as an Army recruiter and public relations officer and my college training in public relations helped a lot. It kept me from getting discouraged when people or churches said no, we’re not interested. I just moved on to the next person. I didn’t take it personally. Oftentimes, people need to hear the message more than once. The marrow organizations were like, ‘You’re real good at this recruiting, You want to work for us?’ I’m like, ‘No, I’ll just volunteer’. I didn’t know how much time I had left, what my energy level would be from day to day, and needed some recovery time between the drives. You don’t have a lot of patients doing their marrow recruiting.

One reason is that it can feel like begging, which is not the American way. But as the song goes, ‘I Ain’t Too Proud To Beg’. Also, many patients like to keep their diagnoses private. I can understand all of these reasons. It can make it hard for employment if a diagnosis is public, puts the patient in a position of vulnerability, some people don’t like to speak in public (not that I didn’t get nervous myself, which I often did), and many other valid reasons. (Live Video from a Bone Marrow Drive at a church).

During this time, my family had flown up to the Georgetown Medical Center to do some medical research. They tried to get a blood sample from my daughter’s tiny veins in her little arms and were having a hard time drawing a blood sample. They eventually got a sample. Patrice didn’t cry until after they had drawn the sample. We had moved from Detroit in the middle of the school year.

I remember her new first-grade teacher approaching me and asking if I had leukemia because Patrice had told her I had leukemia, and she thought Patrice was making it up. Patrice was doing her part to help her daddy and spreading the word.

Six months after I had moved to Atlanta, I received a phone call from the marrow donor representative in Detroit. She was all excited. She said, ‘You remember that church with the two little girls that only had two people show up. They just set a world record. 5,000 people came out for a little girl with leukemia.’

In September 1996, I went to the last of four marrow drives that Cecelia’s aunt (who I also refer to as Aunt), Rosetta, had organized, about two hours away, in Columbus, Georgia. Upon arriving, I heard that a local well-known businessman who owned a few car dealerships, a stranger to me, had come in earlier and was looking for me but had to leave. About an hour later, he came back and had this intense look in his eyes. We grabbed a table off to the side. He told me he had seen the TV promotions I did for the drive. He proceeded to tell me his story of having hairy cell leukemia and being near death, but the doctors at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston Texas, turned the leukemia around.

He was diagnosed six months before I was. Although praising the life-saving efforts of the marrow drives, he added, ‘But you need to get to MD Anderson ASAP.’ As he left, he stressed ‘one cancerous cell becomes two, two becomes four, four becomes eight, and so forth’. He then handed me a card with the contact information for MD Anderson. He was paying his blessing forward. He also continues to thrive 30 years later.

When I arrived back home in Atlanta, I called the number and, miraculously and almost simultaneously, my future nurse and doctor answered the phone; something that never happened again in all my years as a patient. After our conversation, it was decided that I should go to MD Anderson. A few days later, I was on my way to Houston, Texas, on a corporate jet, courtesy of the Corporate Angels.

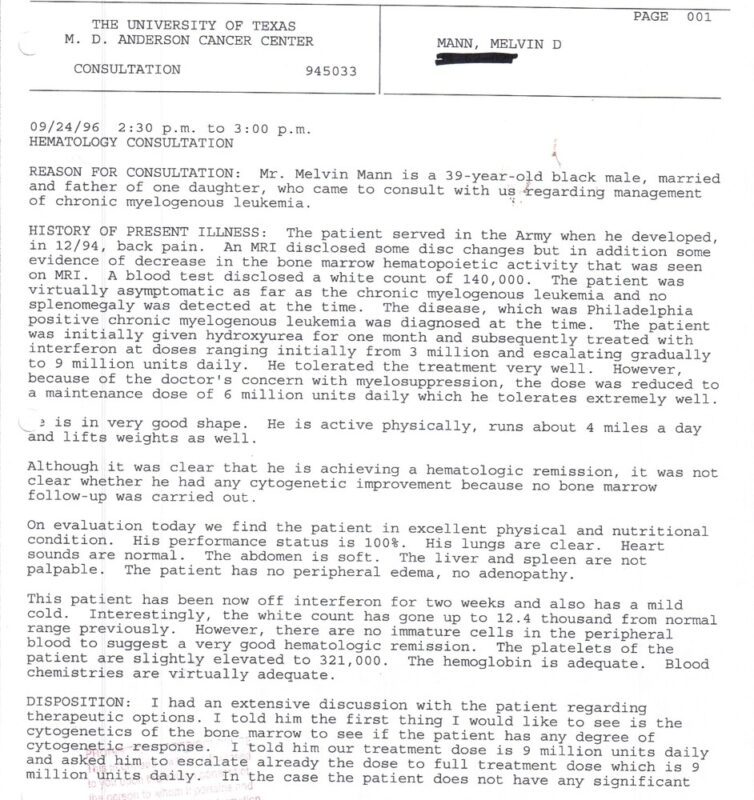

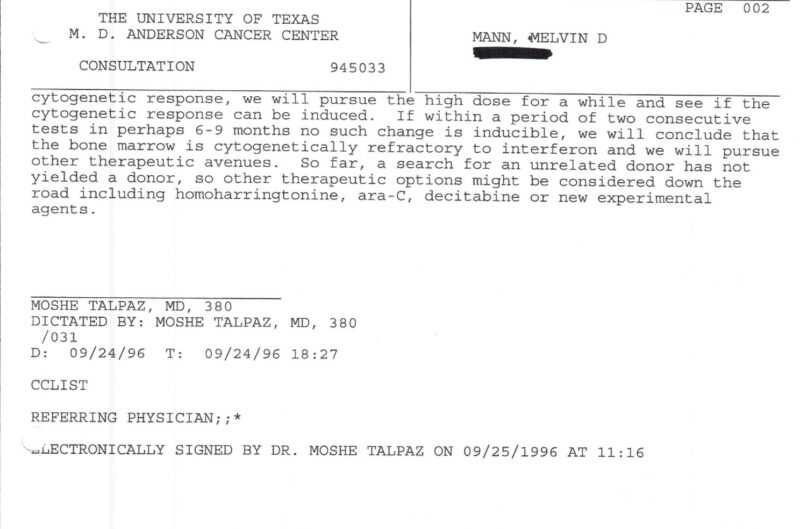

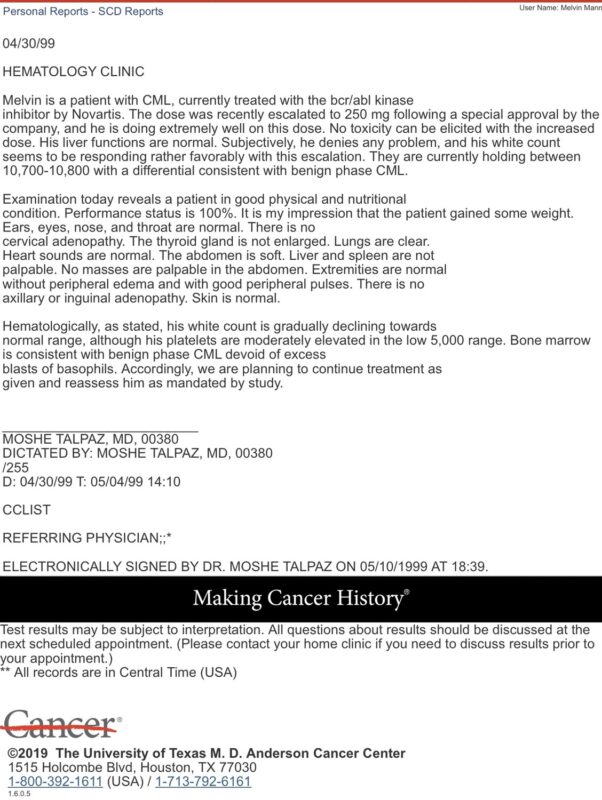

When I met my doctor at MD Anderson, I discovered he was the first doctor to use interferon for CML, which was the first-line therapy at the time. He carefully reviewed my records and said, ‘We still have time. I’m going to increase your dose of interferon and put you on clinical trial after clinical trial.’

This was the first time in the 20 months since my diagnosis that I was informed of and asked to participate in a clinical trial. I realized that I had kind of experienced a 20-month delay in the possibility of having the option to receive the latest breakthrough medical treatment.

It is often stated that some patients, especially some African Americans, are afraid they will be taken advantage of in clinical trials because of the past legacy of unethical experiments, including the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study (Tuskegee Syphilis Study Background Information). Approximately only five percent of all patients participate in clinical trials and only five percent of that five percent are black. In other words, the fear of participating on the front end can prevent you from reaping the benefits on the far end.

Initial Visit to MD Anderson

During this time, I also continued my involvement with marrow drives. Although thousands of people were joining the marrow donor list, and donors were being found for others, I could not find my donor, as was made clear to me three years earlier. The DOD even flew me up to Med Star Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C. to be with my best Army pal as he donated marrow. Although he joined the marrow registry in hopes of helping me, he ended up matching and donating to a stranger. I was proud of my friend. His compassion was first class and he went up another notch in my book.

In the summer of 1997, I was at a bone marrow donor meeting in Washington, DC. Unknownst to me, I was getting a bit popular. This lady comes up to me and says, ‘Oh there you are, I have been looking all over for you. I have my whole basement plastered with your posters.’

This famous physician, who had done one the first marrow transplants was standing there with me and said, ‘Don’t let that go to your head, I’ve seen that mess up many a good man.’ I couldn’t understand why she felt that way, because, on my end, anyone who joined the registry was more of a hero than me and also she just had a drive that recruited 3,000 donors.

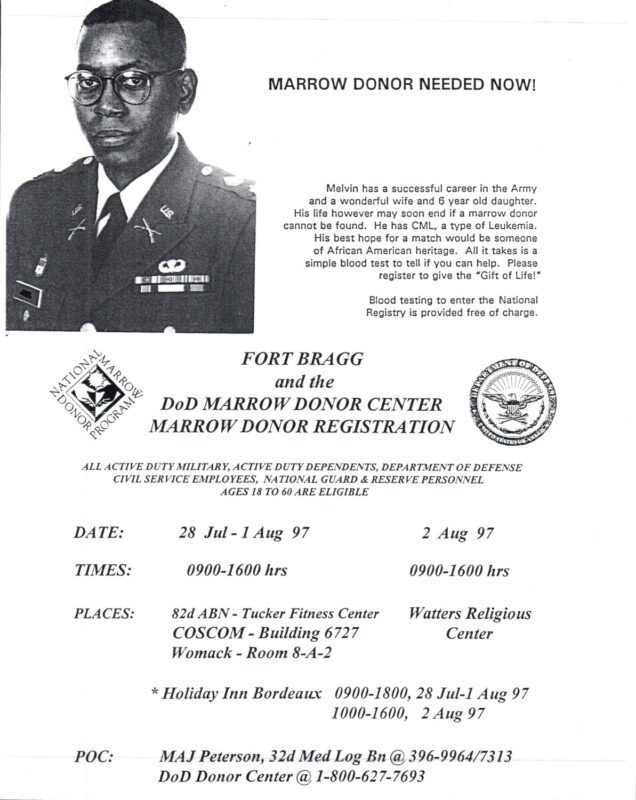

It was years later before I could look back and appreciate my contribution to recruiting donors, and the same thing with clinical trials. I believe this is true in a lot of people in my situation because we are not doing anything by ourselves but with the help of so many others. Later, at the meeting, this Army major walked up to me and asked me if I could come down to Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, NC.

I greatly admired him because of his commitment to the cause. He said that they were planning a drive with the Army, local civilians, and a well-known businessman who had CML. He said they didn’t know how many people to set for a goal and the businessman asked what the world record was.

Someone told him 5,000 (From that church I spoke at with the two little girls). So the businessman said, ‘We’ll do 10,000.’ Some thought this goal was a ‘bridge too far.’

So the Army major asked me to come down, share my story, and help out with the publicity. The drive ended up setting a world record of 10,675 people joining the registry in a single drive. That was 23 lives saved, because, from every 430 people who join the registry, a life is saved. This drive took all week. I was honored that I was able to play a small part in it.

Back then, joining the marrow registry required people to show up in person and give two tablespoons of blood.

Click here to see the promotional video from Fort Bragg World Record Marrow Drive.

There would be people lined up all down the hallways and out the doors volunteering to join the registry. Now people can order a free at-home cheek swab marrow donor kit to join the marrow donor registry.

As time was ticking down, I became very frail and fatigued. The interferon, as well as other experimental drugs, had stopped working. I would wake up in the morning feeling like I never went to sleep. A lifelong runner, I remember looking out the hotel window at the Rotary House International at MD Anderson, thinking about going for a jog, but realizing that I couldn’t jog even one city block.

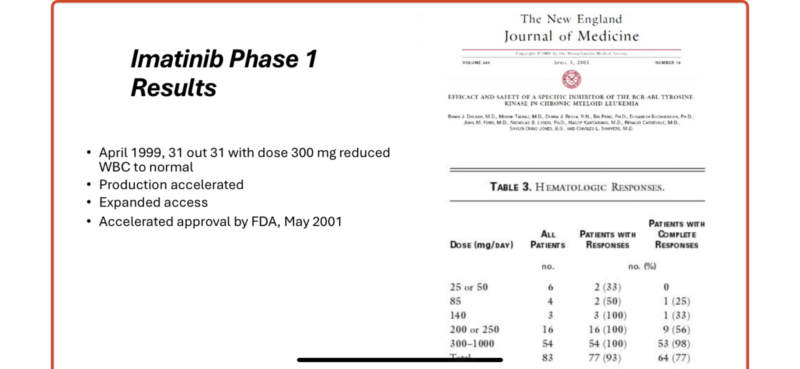

With hope diminishing, at the end of January 1998, I asked my doctor when a new drug was expected. He said a drug called STI571 was close, but they were having problems in the labs, in the livers of animals, and that I would be the first patient to try it at MD Anderson if it was ever approved for an experimental trial in humans. His nurse reminded him that he told someone else the same thing. He replied, ‘OK, you’ll be number two’. I flew back home to Atlanta.

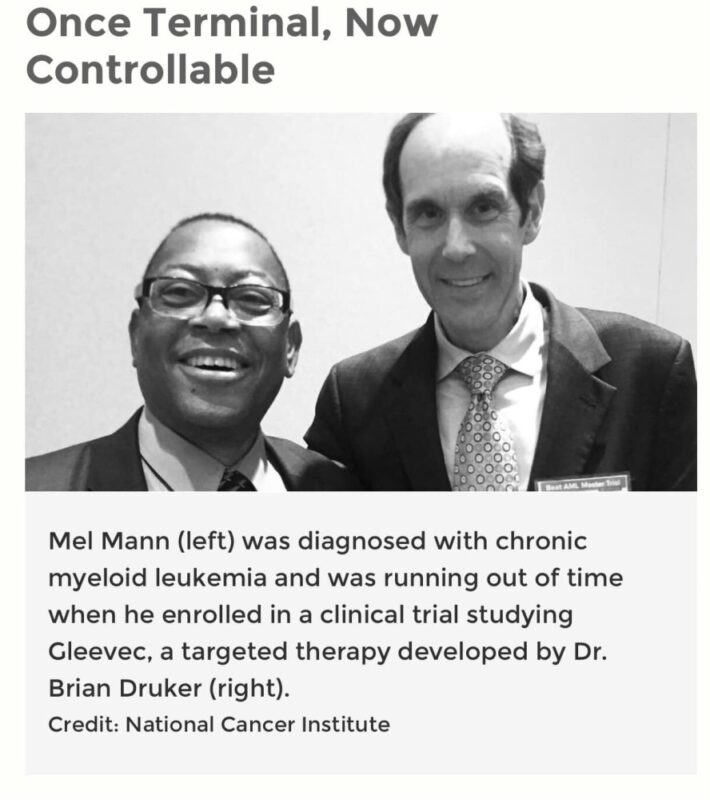

Finally, in August 1998, MD Anderson got approval to start a phase 1 clinical trial on STI571. Elated, I traveled back out to Houston and became the second patient at MD Anderson to use STI571. I entered the trial on 3 August 1998. The purpose of the phase I clinical trial was to test the safety of the drug in humans, find the dose at which the drug should be given and possibly see any early signs of drug efficacy. I was not promised miraculous results, but the trial gave me hope of extending my life. I had read somewhere, to never lose hope, because if you lose hope, you’re finished. I also knew that, at the very least, my participation could help other patients on their cancer journeys.

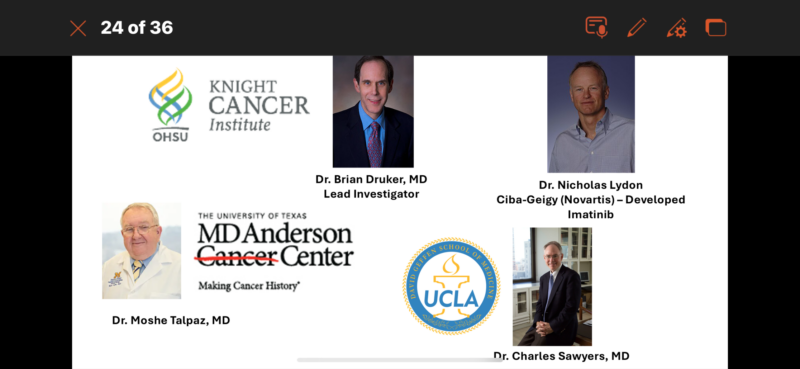

The clinical trial took place at three major health centers. In addition to MD Anderson, the other sites were Oregon Health and Science University in Portland and UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles. Speaking of Oregon, I remember meeting this guy named Sonny at a party at my brother-in-law’s house in Alabama a few years earlier, who had CML and had been traveling way out to Oregon for treatment.

He was a Black guy and had received a bone marrow transplant. He was one of the few Blacks and the only Black person I knew who had received a bone marrow transplant. I wondered why he was going to Oregon, past all these other great cancer centers. I reasoned he must not have known any better. But, he had found a donor and I had not. Turns out that Oregon was where Dr. Druker, the research physician behind Gleevec worked.

Only twenty patients could participate in phase 1 of the clinical trial at each site, and we had to remain close to the trial site, so I rented an apartment in Houston. I made friends with some of the other patients on the trial as we conversed in the waiting room. I don’t recall seeing any other blacks on that part of the trial. One day I asked the nurse how the first guy to take the medicine was doing. She said he didn’t make it. She must have seen the expression on my face. She said not to worry because everyone responds differently.

Also, the later the people joined the trial, the better they did, because they were on a higher dose of the drug. Sometime later, before one appointment, an elderly lady who looked remarkably like a very frail clinical trial patient I had seen before, powerwalked passed me as she came out of the doctor’s office and sprinted towards the elevator. I chased after her and asked her, as she was getting on the elevator, ‘Aren’t you the woman normally in the wheelchair’ She said, ‘Yes’, as the elevator doors closed. I knew then that this STI571 was my Hail Mary drug. She was on a higher dose, so I knew I would get there too.

I was just on a very low dose, far less than the 300 where most everyone started responding. The standard dose is 400 mg. All the patients at my dose had been taken off the study because they did not respond and their counts were escalating upwards. All except me.

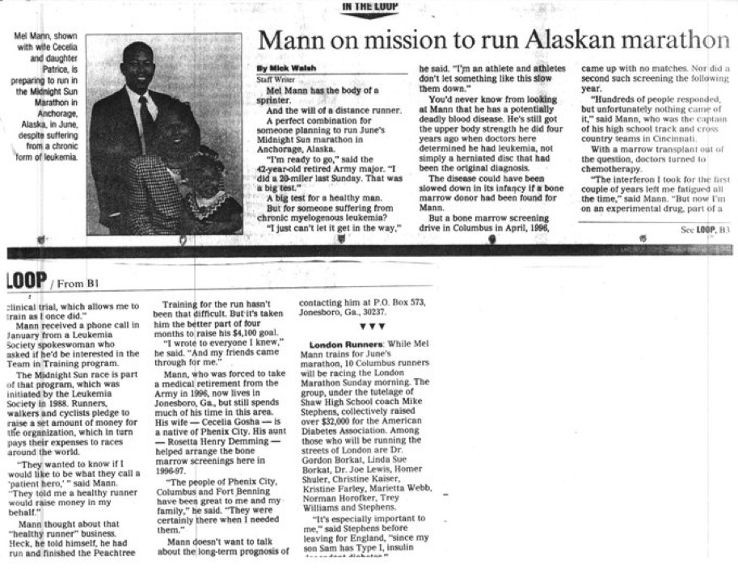

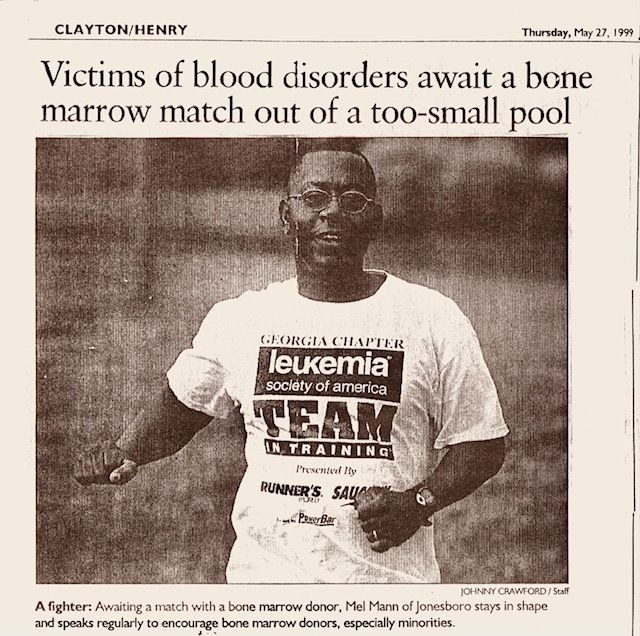

I had amazing results with STI571. In January 1999, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society contacted me and asked if I wanted to be something called a patient hero. They said some people would run a marathon in my honor and raise money for cancer research. LLS had played a part in the funding of STI571.

I had been the captain of my high school cross-country and track teams. Twenty-seven years earlier, in 1972, when I was 15 years old, I had qualified for the Boston Marathon with 20 minutes to spare when I ran the 26.2 mile Cincinnati Spartan Marathon for fun during an off-season cross country period. I had never run more than eight miles in practice. Everyone was saying that my marathon time was one of the best times in the country for a sophomore.

The only problem was, that you had to be eighteen years old to run in the Boston Marathon. I was too young, so I never ran another marathon and stayed with the shorter high school middle distances.

High School Running Days

I had always wanted to do another marathon since that solo high school effort but had never gotten around to it. I had thought about that experience the previous year when I was not responding to treatment and I had to undergo apheresis treatment. My white cells were way high again and they had to filter the bad cells out of my blood. I lay in this bed as the blood flowed out of one arm into this machine and the filtered blood flowed back into the other arm. The doctor had told me it would take about three hours for each apheresis procedure.

I remember thinking I could do this uncomfortable procedure because that was close to the time I ran the marathon when I was fifteen.

So when I was asked about being a patient hero, I pretty much knew my body and what was required to run a marathon, so I said, I’ll do the patient hero marathon myself and raise the money also. By the time of the marathon, MD Anderson had received special approval to raise my dose to 250 mg daily, so my blood essentially returned to normal range.

So, six months later, in June 1999, I ran the 26.2-mile Mayor’s Midnight Marathon in Alaska and completed a 111-mile bike ride in Tucson in November 1999 for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society’s Team in Training. So much for the first oncologist’s advice, “Don’t run any marathons.” For these events, and another 26.2-mile marathon in 2005, in Vancouver, Canada, I raised a sizable amount of money for future leukemia research. A lot of my high school and college friends, family, church members, and so forth gave me money. I got money from strangers also.

Columbus Times

Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Also, I never stopped recruiting for marrow donors, even though I had STI571. There was a period before the doctors felt certain that STI571 was superior to bone marrow transplants. I knew marrow transplantation could help cure 60 other diseases, including sickle cell anemia and the need was still there.

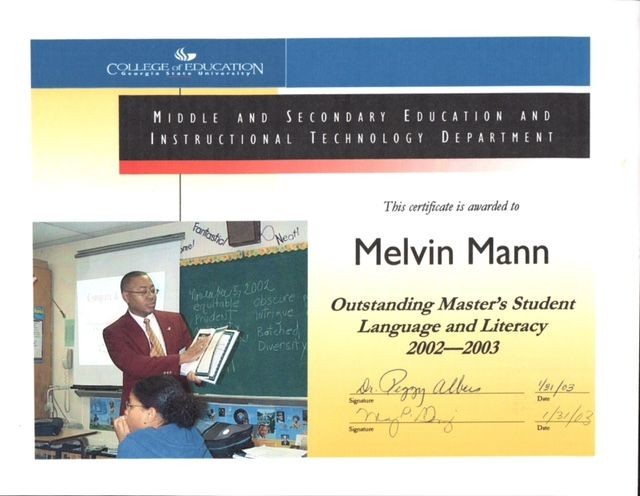

In January 2000, I went back to school. I received a BA in English Literature, Man. Ed. in Secondary English, and a license to teach.

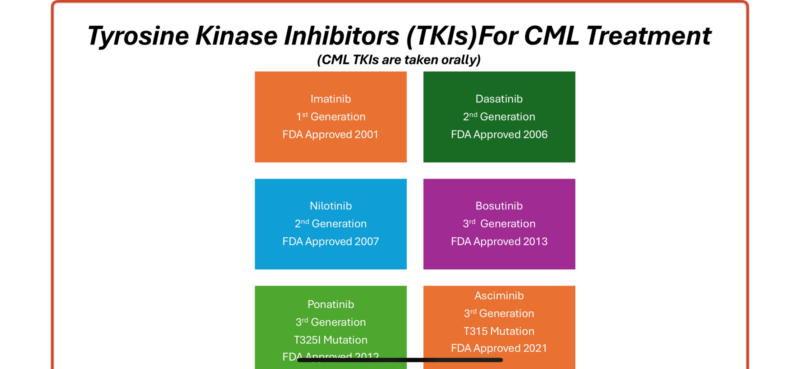

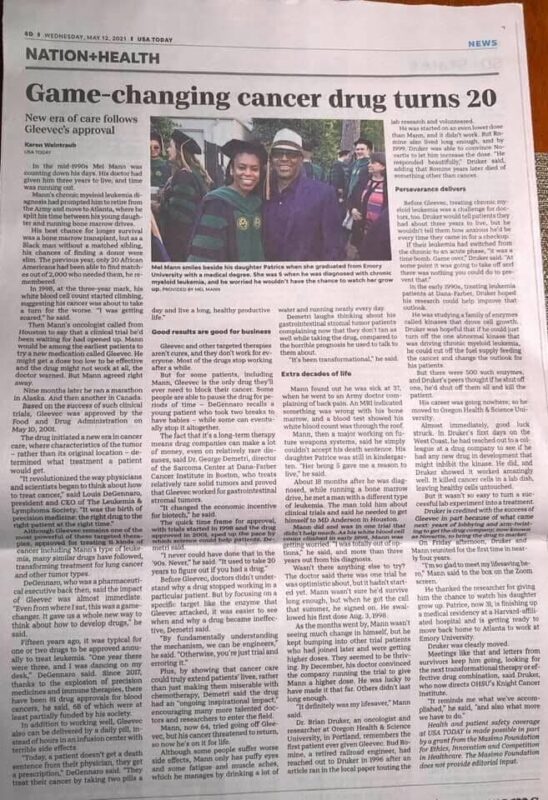

On May 10, 2001, the FDA approved STI571 now known as Gleevec (Imatinib). This was the quickest FDA approval of a drug on record. Currently, I am blessed to still be the world’s longest-living Gleevec survivor (as I was in 1998) out of over the 500,000 people using Gleevec and the millions of people using second and third-generation versions of this type of drug. Gleevec was the first Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKI) because it targets the tyrosine kinase protein. TKIs can treat other forms of cancer such as breast, lung, renal, and stomach cancers. Gleevec treats about 12 different malignancies.

Read Details of the Gleevec Clinical Trial.

There are now several generations of Imatinib, which is great for the small percentage of patients who do not respond to Imatinib or who develop resistance to Gleevec. There are over 80 FDA-approved TKIs.

I continued on the trial, even after the approval of Gleevec until the Spring of 2002. I had 12 of those bone marrow aspirations on the trial, had stayed at MD Anderson for three months, and made repeated trips back and forth every 90 days during those four years, as there was a phase IV to the trial because of its accelerated approval.

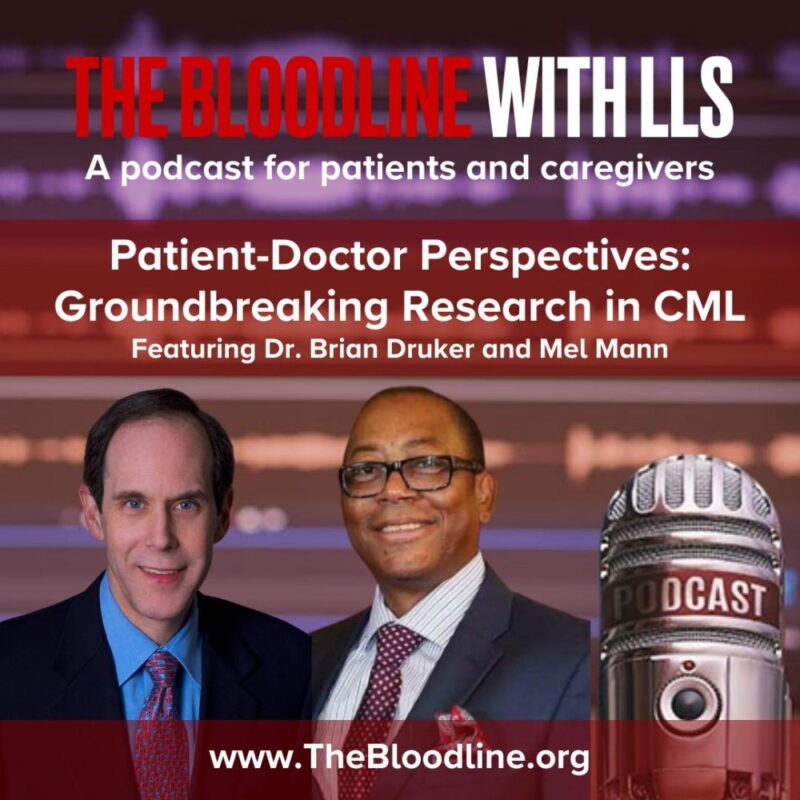

(With Dr. Brian Druker, MD, at the 2017 ASH Conference, Atlanta Georgia. Dr. Druker, Director of the Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health & Science Institute, is the physician-scientist behind the development of Gleevec.)

Undergoing a clinical trial isn’t easy. For me, it came with my fair share of progress and setbacks. But all along I maintained hope that the next drug would be the one to save my life. There were the additional expenses of living in a different for three months, finding an apartment, the monthly trips back and forth to Houston, being separated from my family, and all the miscellaneous fees.

USA Today Supplement Feature Story

Occasionally, during my appointments at MD Anderson, I bump into other trial patients and reminisce about the old days. We know that we were on the front lines of a clinical trial that is now a standard treatment and is saving the lives of patients who in the past were incurable. I did not know any long-term CML survivors. Now we can give hope to those who are newly diagnosed with CML. We took an uncertain hopeful path, and it led to a bright future for us — and for countless others.

MD Anderson Video on how a Clinical Trial and Gleevec saved Mel Mann’s life.

My daughter eventually got the hang of riding that little pink bike, graduated high school, Harvard College, Emory Medical School, and is a physician herself. I would like to thank her, Cecelia-my wife of forty years, family, friends, countless strangers, church family, the military, my cancer support group, and the medical community for the overwhelming support they provided throughout my cancer journey. They gave me hope — hope for a healing that I thought could only come from finding a matching bone marrow donor, which I never found for myself. Instead, my healing came from a drug that was only a gleam in Dr. Druker’s eye at the time of my diagnosis. A clinical trial is an opportunity to get tomorrow’s medicine today.

Listen as Dr. Druker and I discuss the history of Gleevec.

My wife and I, continue to volunteer for various national cancer and marrow donor organizations such as Be The Match. I was instrumental in taking the Leukemia and Lymphoma’s pilot program Myeloma Link, which spreads blood cancer awareness to Black communities, from two cities to 13 cities nationwide.

I have traveled throughout the United States telling my story, spreading cancer awareness, and advocating for clinical trials, and marrow donors. I have spoken in places ranging from churches to large corporations. I am exhibit A of why patients should consider clinical trials. As one little ninety-year-old lady at an African American church came up to me after one of my talks and quoted a scripture out of Genesis, ‘What was meant for bad, God uses for good’. I look forward to sharing my story with you or with your organization. God Bless.

10 May 2021 USA Today Article.

National Television Commercial — Mel’s Leukemia Story.

Cecelia, Mel, and Patrice at the Atlantic ‘People v Cancer’ vide.o

Leukemia Survivor, Jermaine and his marrow donor Montrell discuss their experience Video.

Leukemia Survivor, Jermaine and his marrow donor Montrell discuss their experience Vide.o

With Be The Match at Morehouse College Video

Myeloma Link Interview in Philadelphia

With Local ABC News Reporter:

- Saint Louis MO Myeloma Link Interview

- Free cheek-swab at-home marrow donor kit

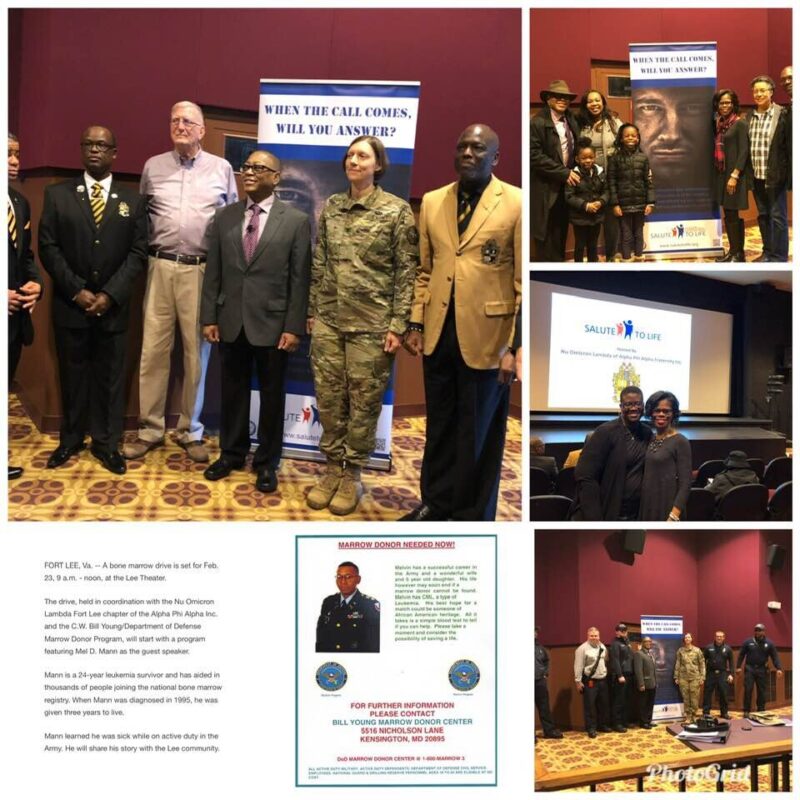

2019 Fort Lee Virginia, Bone Marrow Drive

Dear Cancer Patient, Here’s What I Learned on My Cancer Journey.”

More posts featuring Mel Mann.