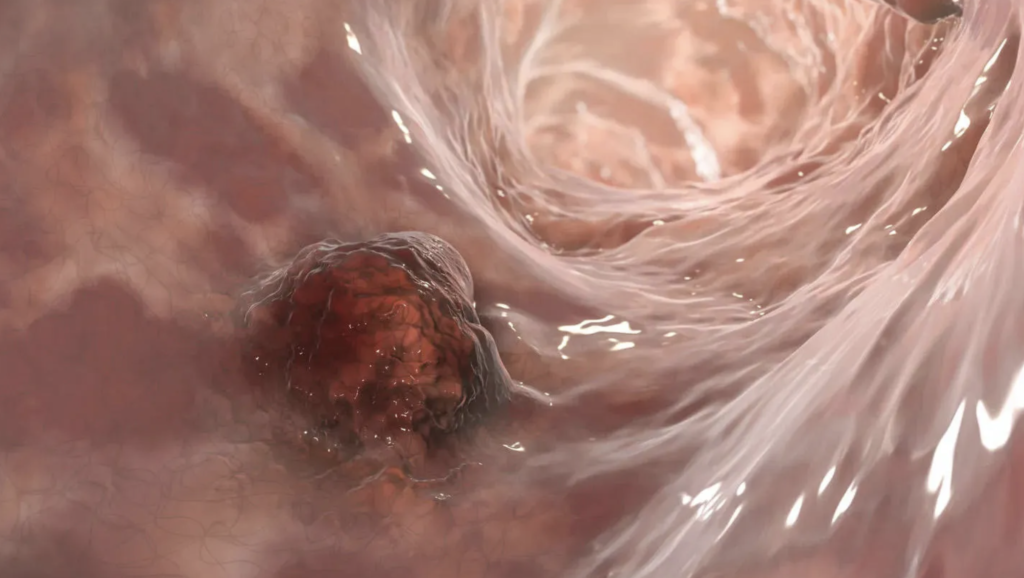

Researchers from the University of Birmingham, in collaboration with the University of Glasgow, have uncovered a potential use of bacterial therapies to combat bowel cancer.

This innovative research, funded by Cancer Research UK, explores the use of genetically engineered Salmonella bacteria to assist the immune system in targeting cancer cells. The findings, published in EMBO Molecular Medicine, could lead to the development of novel therapies aimed at treating colorectal cancer, which is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the UK.

The study specifically investigates how Salmonella, a bacteria modified for safety, interacts with T cells, which play a crucial role in the body’s defense against cancer. The research team discovered that Salmonella works by depleting asparagine, an essential amino acid that cancer cells need to thrive. While this depletion slows tumor growth, it also interferes with the function of T cells, reducing their ability to attack cancer cells effectively.

In response to these findings, the research team proposes a solution: genetically modifying the Salmonella bacteria to avoid targeting asparagine. This adjustment could help preserve the effectiveness of T cells, allowing them to work synergistically with the bacterial therapy to better combat cancer. This research opens up exciting possibilities for the development of more effective bacterial-based cancer therapies, potentially offering a new way to treat colorectal cancer and improving patient outcomes.

Lead researcher Dr Kendle Maslowski, of the Cancer Research UK Scotland Institute in Glasgow and the University of Glasgow, said:

“We know attenuated Salmonella and other bacteria have the power to tackle cancer, however until now it was not known why it was not proving as effective as it should be. Our research has discovered that it is an amino acid called asparagine that the bacteria attacks which is essential for T cells to be activated. We believe this knowledge could enable bacteria to be engineered not to attack asparagine allowing the T cells to act against the tumour cells leading to new effective treatments for cancer.”

About Salmonella

Salmonella is a genus of gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family. The two primary species are Salmonella enterica and Salmonella bongori, with S. enterica being the more prevalent species. This species is further divided into six subspecies, which collectively encompass over 2,650 distinct serotypes. The genus is named after Daniel Elmer Salmon, an American veterinary surgeon who played a key role in its discovery.

Salmonella bacteria are non-spore-forming, primarily motile organisms that possess peritrichous flagella—flagella distributed around the cell—allowing them to move efficiently. Their cell size ranges from 0.7 to 1.5 micrometers in diameter and 2 to 5 micrometers in length. Salmonella species are chemotrophs, meaning they obtain energy through oxidation and reduction of organic compounds, and they are facultative anaerobes, which means they can generate ATP (adenosine triphosphate) in the presence of oxygen or by anaerobic pathways when oxygen is scarce.

Salmonella is an intracellular pathogen, and certain serotypes of the bacteria are responsible for diseases like salmonellosis, primarily transmitted through contaminated food, typically from fecal matter. Typhoidal Salmonella serotypes are unique in that they are humans-only pathogens, causing illnesses like typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever. Typhoid fever is particularly severe, as the bacteria invade the bloodstream and spread throughout the body, secreting endotoxins that can lead to septic shock and require urgent medical care and antibiotic treatment. On the other hand, nontyphoidal Salmonella serotypes are zoonotic, meaning they are typically transmitted from animals to humans, causing symptoms primarily in the gastrointestinal tract. While most cases resolve without antibiotics, nontyphoidal infections in sub-Saharan Africa can be more invasive and require treatment with antibiotics.

Bacterial therapies at 19th century

Bacterial therapies, which date back to the 19th century, have long been recognized for their potential in treating diseases, including cancer. However, their use was largely set aside due to concerns over safety. Recently, with advancements in genetic modification, researchers have revisited bacterial therapies, exploring ways to make them both safe and effective as potential cancer treatments. This resurgence has brought new hope for tackling colorectal cancer, a major cause of cancer-related deaths.

While attenuated Salmonella and other bacteria have been recognized for their ability to combat cancer, their effectiveness has been limited. Dr. Maslowski explained that the bacteria were attacking asparagine, an essential amino acid for the activation of T cells—the immune cells responsible for targeting cancer. The depletion of asparagine was preventing T cells from effectively attacking tumors. This discovery is pivotal because it provides insight into why bacterial therapies haven’t been as successful as hoped.

The researchers propose that by genetically engineering Salmonella to avoid depleting asparagine, they could allow T cells to function properly, enhancing the immune system’s ability to target and destroy cancer cells. This insight could lead to the development of new, more effective cancer treatments by leveraging genetically modified bacteria to work alongside the body’s immune defenses.

With around 16,800 deaths annually in the UK alone due to bowel cancer, this innovative research offers a renewed sense of hope. The potential for genetically engineered bacteria to improve cancer treatment could significantly impact the fight against one of the most deadly cancers, leading to better survival rates and more effective therapies in the future.