Prognosis refers to the likely course and expected outcome of a disease. In the context of cancer, it helps describe how the illness may progress, the chances of recovery or recurrence, and overall survival expectations. A prognosis is shaped by both medical evidence and individual patient factors, and while it is based on statistics, it does not predict exactly what will happen to a specific person.

In this article, we’ll explore the different elements that influence a cancer prognosis—such as the type and stage of cancer, tumor biology, and patient health. We’ll also look at how doctors estimate prognosis using staging systems, molecular markers, and survival rates. Additionally, we’ll discuss how prognosis is used in treatment planning, what it means for patients and families, and the importance of clear, compassionate communication when discussing it.

Key Factors That Influence Cancer Prognosis

Several important factors influence a person’s cancer prognosis, each contributing to how the disease is likely to behave and how well the patient may respond to treatment.

One of the most significant is the type and subtype of cancer. Some cancers, like pancreatic or glioblastoma, are known for being aggressive and fast-growing, while others, such as thyroid or low-grade prostate cancer, often progress slowly and respond well to treatment. Even within a single type of cancer, the subtype can make a big difference—hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, for example, usually has a better prognosis than triple-negative breast cancer.

Another major factor is the stage at diagnosis, which refers to how far the cancer has spread in the body. Early-stage cancers that are still localized are often more treatable and have a better outlook. In contrast, metastatic cancers—those that have spread to distant organs—tend to be more challenging to control and are associated with lower survival rates. Tumor grade also plays a role. This describes how abnormal the cancer cells look under a microscope. Low-grade tumors tend to grow slowly and behave less aggressively, while high-grade tumors often grow and spread more rapidly.

At the molecular level, specific genetic markers and mutations can influence both prognosis and treatment options. For instance, the presence of mutations like EGFR or ALK in lung cancer, or HER2 overexpression in breast cancer, may affect how the cancer behaves and also identify opportunities for targeted therapy. BRCA mutations, commonly associated with breast and ovarian cancer, carry both prognostic and familial implications.

Lastly, a patient’s individual health factors matter greatly. Age, overall health, organ function, and performance status—which refers to how well a person can carry out daily activities—can all affect prognosis. People with significant comorbidities or frailty may face more challenges during treatment, which can influence both outcomes and treatment choices.Together, these elements form the basis for a comprehensive prognosis and guide clinicians in tailoring care to each patient’s unique situation.

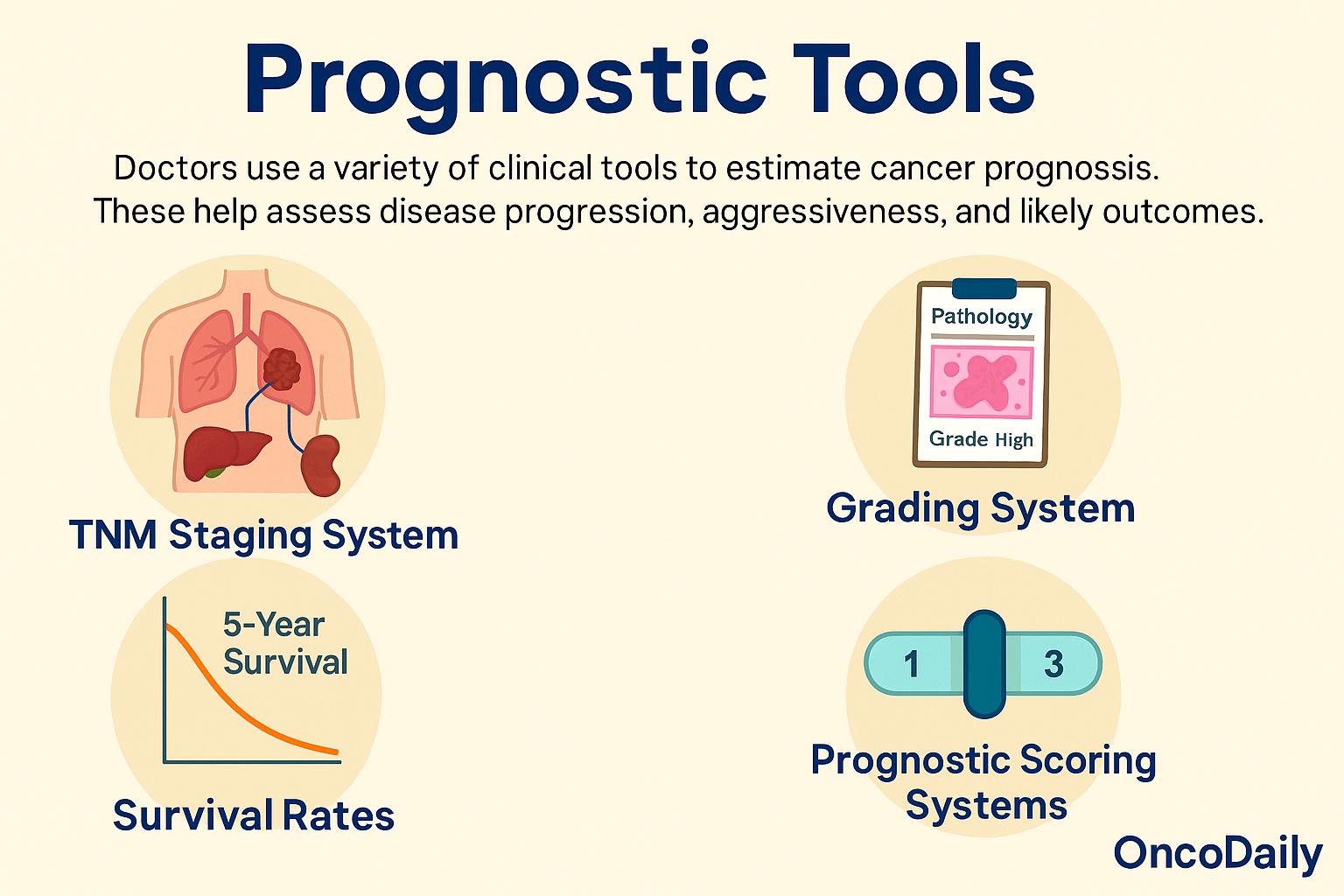

Common Prognostic Tools and Measurements

Doctors use a variety of clinical tools to estimate a patient’s cancer prognosis. These systems help provide a clearer picture of how far the disease has progressed, how aggressive it may be, and what the likely outcomes are. They also serve as a common language among medical professionals to guide treatment planning and discuss risk with patients.

One of the most widely used systems is the TNM staging system, which stands for Tumor, Node, Metastasis. This classification describes the size and extent of the primary tumor (T), whether cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N), and whether it has metastasized to distant organs (M). For example, a cancer staged as T1N0M0 would be a small, localized tumor with no spread, generally indicating a better prognosis than a T4N2M1 cancer that is large and has both nodal and distant spread.

Grading systems also play a key role. These assess how abnormal the cancer cells appear under the microscope. For example, the Gleason score is used in prostate cancer to grade the pattern of cancer cell growth; higher scores are associated with more aggressive disease and a greater likelihood of progression or recurrence. Doctors also use survival rates to help communicate prognosis.

The most commonly cited is the 5-year survival rate, which refers to the percentage of people who are still alive five years after their diagnosis. Other measures include median survival (the time at which half of the patients are expected to be alive) and disease-free survival, which tracks how long a person remains free of cancer after treatment. These statistics are drawn from large populations and help frame expectations, though they don’t predict individual outcomes.

Some cancers also use prognostic scoring systems that combine different factors into a single score. For instance, the Nottingham Prognostic Index in breast cancer incorporates tumor size, lymph node involvement, and tumor grade to estimate the risk of recurrence and guide treatment decisions. Together, these tools allow oncologists to tailor treatment strategies to the individual patient’s disease characteristics and overall health. They also help patients and families better understand what to expect, while still recognizing that every case is unique.

Why Prognosis Matters

Understanding a cancer prognosis serves several important purposes beyond just predicting survival—it plays a central role in planning and decision-making throughout a patient’s care.

First and foremost, prognosis helps guide treatment decisions. For example, a person with a very favorable outlook may opt for less aggressive therapy to preserve quality of life, while someone with a higher-risk cancer may choose more intensive treatment to try to extend survival or reduce the chance of recurrence. In this way, prognosis allows care to be tailored not only to the biology of the disease but also to the patient’s goals and values.

A clear prognosis can also help patients and their families plan for the future—whether that means making important personal or financial decisions, preparing for possible lifestyle changes, or considering palliative or end-of-life carewhen appropriate. While these conversations can be emotionally difficult, they empower patients to maintain control and make informed choices about their lives and care. Importantly, prognosis supports shared decision-making between the patient and the medical team. It helps open up honest, compassionate discussions about risks, benefits, and expectations. This process builds trust and ensures that the care plan reflects not only medical reality but also the patient’s preferences and quality of life.

Finally, it’s essential to remember that prognosis is not destiny. While it can provide useful guidance and context, it is based on averages and probabilities—not certainties. Many patients defy the odds in both directions. For some, a good prognosis brings reassurance and hope; for others, even a challenging outlook can motivate strength and resilience. What matters most is using prognosis as a tool for understanding and planning, not as a fixed prediction of what lies ahead.

The Role of Biomarkers in Modern Prognosis

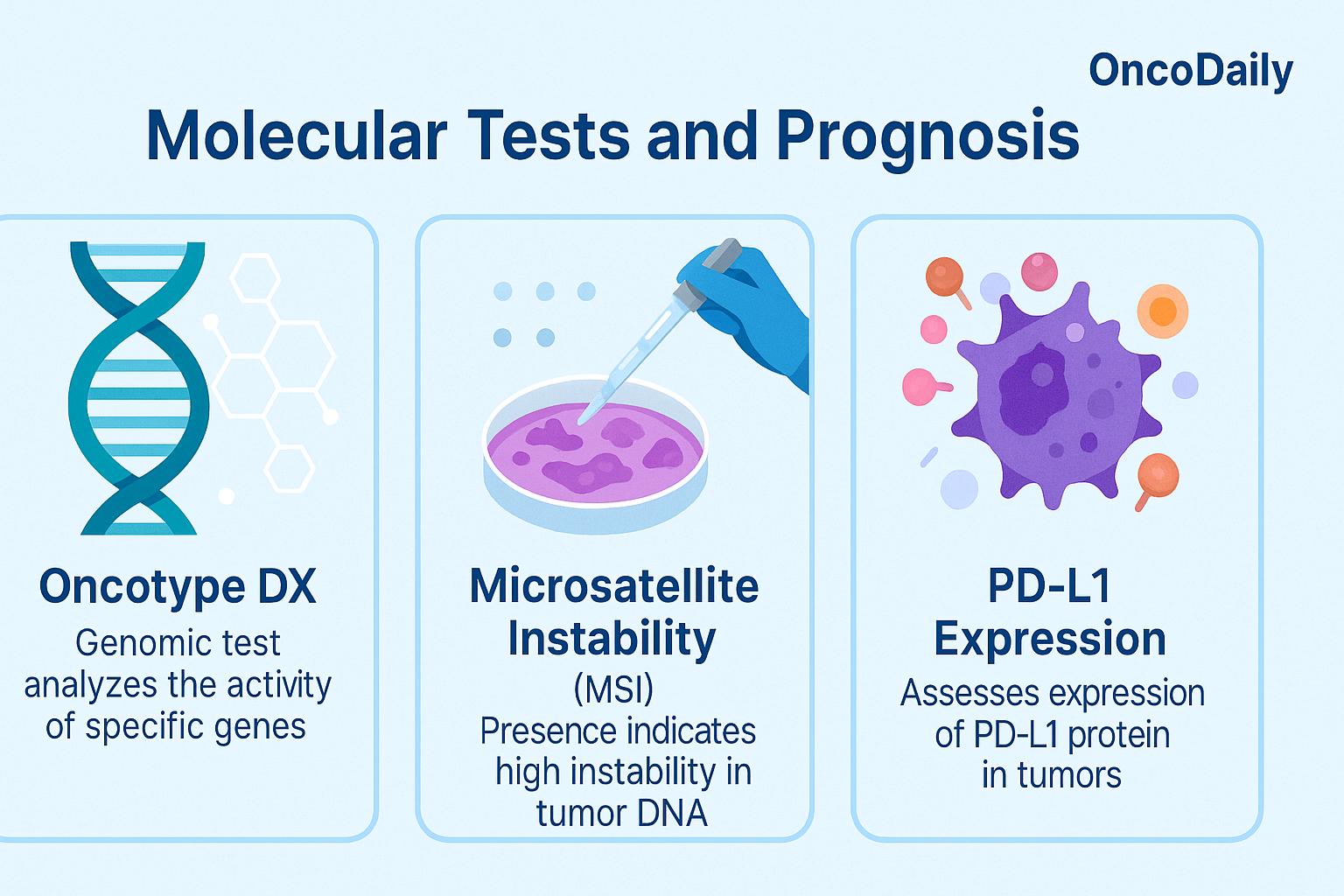

In recent years, molecular and genetic testing has transformed how doctors estimate cancer prognosis, moving beyond traditional factors like tumor size and stage to more precise insights based on a tumor’s biological behavior. These tests analyze genes, proteins, and other molecular features to provide a deeper understanding of how a specific cancer is likely to grow, spread, or respond to therapy.

One important example is Oncotype DX, a genomic test used in early-stage hormone receptor–positive breast cancer. It examines the activity of 21 genes within the tumor to produce a recurrence score, which helps predict the likelihood that the cancer will return after surgery. This information not only informs prognosis, but also whether a patient is likely to benefit from chemotherapy—making it both a prognostic and predictive test. In colorectal cancer, testing for microsatellite instability (MSI) or deficient mismatch repair (dMMR) provides valuable prognostic insight.

Tumors with high MSI tend to have a better prognosis in early stages, and this molecular feature also predicts a better response to immunotherapy, particularly in advanced disease. So again, MSI status serves a dual role—indicating both likely outcomes and potential treatment benefit.

In non-small cell lung cancer, PD-L1 expression is measured using immunohistochemistry to help guide immunotherapy decisions. High levels of PD-L1 are associated with a better response to checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab. While primarily used as a predictive biomarker, PD-L1 may also offer some prognostic value, as its expression is sometimes linked to more aggressive tumor behavior.

These types of molecular tests are redefining what it means to estimate a cancer prognosis. Instead of relying solely on what is visible under the microscope, doctors can now look at the tumor’s genetic fingerprint, allowing for more personalized, accurate risk assessments. As a result, patients receive treatments that are better matched to their cancer’s biology—avoiding unnecessary therapies when possible, and targeting aggressive cancers more precisely when needed.

Limitations and Misunderstandings About Prognosis

While cancer prognosis is a helpful guide, it’s important to understand that it is not an exact prediction. Prognostic estimates are based on large population studies—averages collected from many patients with similar diagnoses. However, each person’s cancer journey is unique, and many factors, including treatment response and individual biology, can influence outcomes in unexpected ways.

Prognosis can also change over time. For example, a patient may respond exceptionally well to treatment, reducing the risk of recurrence and improving long-term outlook. On the other hand, if the cancer comes back or spreads, the prognosis may shift. In this way, prognosis is not a fixed label—it’s a dynamic estimate that evolves with the disease and its management.

Above all, it’s crucial to remember that prognostic statistics don’t define a person. While they provide valuable context, they should never take away hope or diminish the importance of individualized care. Some patients outlive the odds, while others may face more difficulty than expected. That’s why doctors consider both the science and the person behind the numbers—offering not just information, but also compassion, support, and tailored treatment plans. In cancer care, statistics are tools, but the focus remains on the patient’s experience and goals.

How to Talk About Prognosis With Patients

Discussing cancer prognosis requires both sensitivity and clarity, as it involves not only medical facts but also deep emotional implications. Doctors must balance honesty with compassion—providing accurate information while being mindful of how that information affects the patient emotionally and psychologically.

Every patient processes a prognosis differently. Some want to know every detail, including statistics and risks, while others prefer to focus on the present and avoid numbers altogether. It’s important for healthcare providers to respect each patient’s preferences, asking how much they want to know and how they’d like information to be shared. This helps ensure that communication is tailored, not overwhelming. There’s also the challenge of uncertainty. Prognosis is rarely black and white; outcomes can vary, and many factors influence what lies ahead. Acknowledging this uncertainty while still providing guidance helps build trust and encourages open dialogue.

Ultimately, prognosis discussions should support shared decision-making. When patients understand their outlook in a way that feels safe and respectful, they’re better equipped to make choices that reflect their values—whether that means pursuing aggressive treatment, focusing on quality of life, or preparing for different possibilities. These conversations aren’t easy, but when handled thoughtfully, they can be empowering and deeply meaningful.

You Can Watch More on OncoDaily Youtube TV

Written by Toma Oganezova, MD

FAQ

What is a prognosis in cancer?

A prognosis is a doctor’s estimate of how a disease like cancer is expected to progress, including the likelihood of recovery, recurrence, or survival.

What factors influence cancer prognosis?

Key factors include the type and stage of cancer, tumor grade, molecular markers, the patient’s age, general health, and how well the cancer responds to treatment.

How is cancer prognosis measured?

Doctors use tools like the TNM staging system, tumor grading, survival rates, and molecular tests like Oncotype DX or MSI status to assess prognosis.

Is a cancer prognosis always accurate?

No. Prognosis is based on statistical averages, not exact predictions. Each patient’s experience may vary significantly from the expected outcomes.

Can prognosis change during treatment?

Yes. A patient’s prognosis may improve with a good treatment response or worsen if the disease progresses. It’s a dynamic estimate that evolves over time.

What is the difference between prognosis and diagnosis?

Diagnosis identifies what disease a person has; prognosis predicts how that disease will likely behave and affect the person over time.

How are biomarkers used in cancer prognosis?

Biomarkers help predict how a cancer will behave and whether certain treatments will work. Examples include HER2, BRCA mutations, PD-L1, and MSI.

Can knowing your prognosis help with decision-making?

Yes. Understanding prognosis allows patients and doctors to make informed choices about treatment goals, quality of life, and planning for the future.

Should all patients be told their prognosis?

It depends on the patient. Some want detailed information, others prefer not to know. Doctors should always tailor communication to patient preferences.

Does a poor prognosis mean there's no hope?

Not necessarily. Many people outlive their prognosis or respond well to treatment. Prognosis is a guide—not a certainty.