What Is Malignant Schwannoma?

Malignant schwannoma, now more commonly referred to as a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), is a rare and aggressive type of soft-tissue sarcoma that originates from the peripheral nerve sheath cells, particularly Schwann cells (Louis et al., 2021). Unlike benign schwannomas, MPNSTs are characterized by rapid growth, local invasiveness, and potential to metastasize to distant sites.

MPNSTs frequently occur in patients with underlying genetic conditions, notably Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), where the lifetime risk of developing MPNST ranges from 8–13%. However, they can also occur sporadically without any known genetic predisposition (Evans et al., 2021).

Schwannoma vs. Malignant Schwannoma: Key Differences

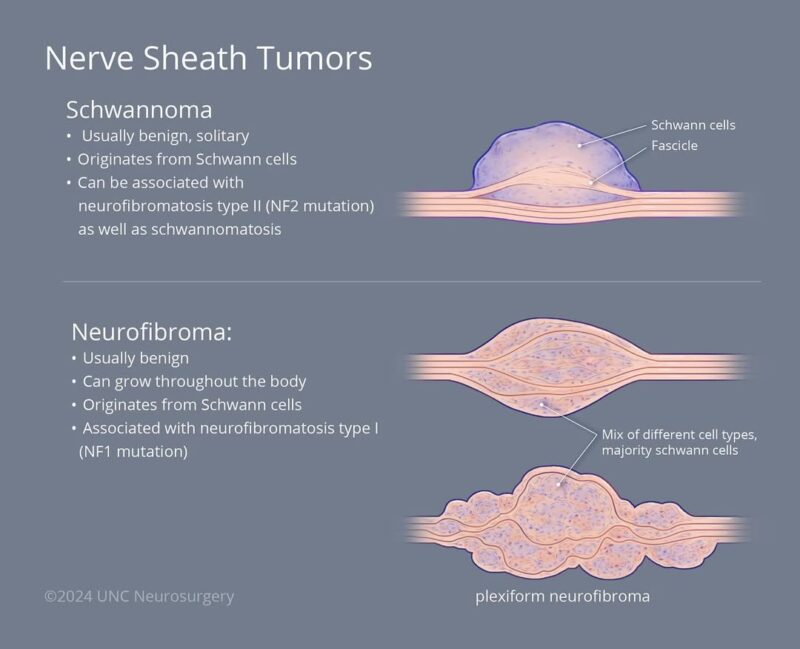

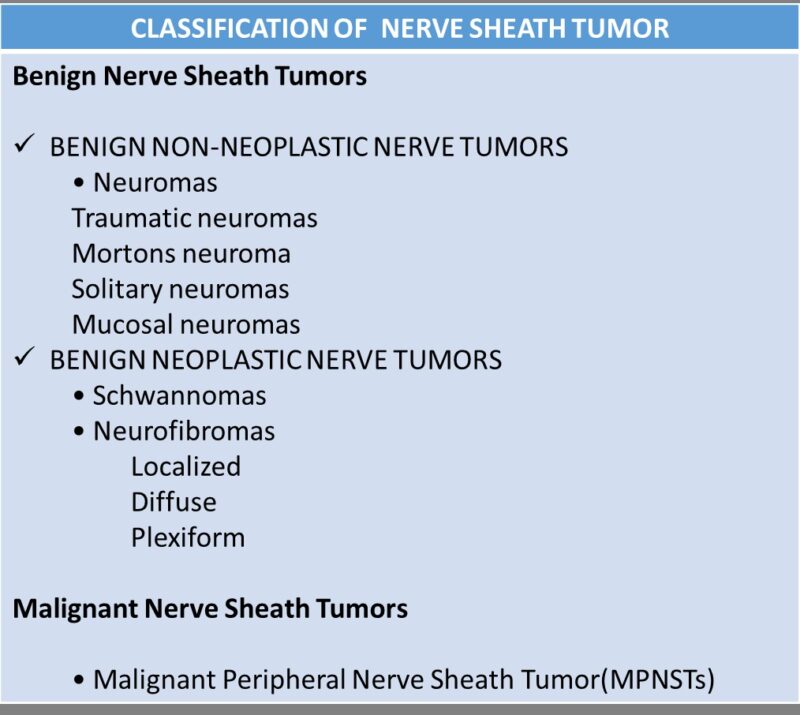

Schwannoma is a benign nerve sheath tumor that originates from Schwann cells, which insulate peripheral nerves. It typically grows slowly, is encapsulated, and does not invade nearby tissues. Schwannomas are often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, though they may cause localized symptoms like pain or tingling if they compress nearby structures. They are usually cured with complete surgical excision and rarely recur.

In contrast, a malignant schwannoma, more accurately termed a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), is a high-grade sarcoma. It is aggressive, can invade surrounding tissue, and often metastasizes, particularly to the lungs. MPNSTs may arise spontaneously, after radiation exposure, or from malignant transformation of a benign plexiform neurofibroma, especially in patients with Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) (Evans et al., 2021; Widemann & Italiano, 2018).

Histologically, schwannomas show strong S100 protein positivity and a biphasic pattern (Antoni A and B areas), while MPNSTs often have reduced or absent S100 expression, high mitotic activity, necrosis, and nuclear atypia.

Summary: Schwannoma = benign, encapsulated, slow-growing, rarely recurs. Malignant Schwannoma/MPNST = malignant, invasive, fast-growing, poor prognosis, especially in NF1.

Causes of Malignant Schwannoma

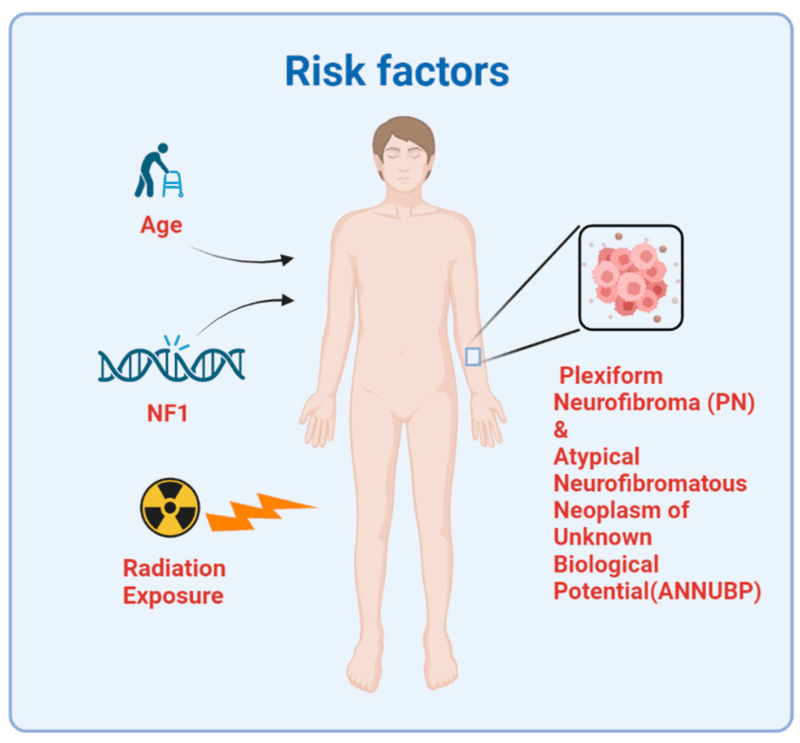

The exact cause of malignant schwannoma, remains incompletely understood. However, several factors have been identified as significantly associated with its development.

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1): One of the strongest known risk factors for malignant schwannomas is Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), an autosomal dominant genetic disorder caused by mutations in the NF1 gene. NF1 is characterized by multiple benign neurofibromas, café-au-lait spots, and an increased lifetime risk (approximately 8–13%) of developing MPNST (Evans et al., 2021). The underlying genetic defect involves the NF1 tumor suppressor gene, resulting in loss of neurofibromin, a protein responsible for regulating cell growth and preventing uncontrolled cell proliferation. Malignant transformation often occurs within existing plexiform neurofibromas in NF1 patients.

Radiation Exposure: Radiation therapy, particularly when administered at younger ages or at higher doses, is another recognized risk factor for developing malignant schwannomas. Patients previously treated with radiation for conditions such as childhood cancers may develop secondary malignancies, including MPNST, within irradiated fields decades later (Widemann & Italiano, 2018).

Sporadic Genetic Mutations: In cases without an identifiable genetic syndrome or prior radiation exposure, sporadic mutations can occur. These tumors may harbor genetic alterations involving tumor suppressor genes such as TP53 and CDKN2A, or receptor tyrosine kinase pathways, though specific causative triggers remain poorly defined. Typically, these sporadic malignant schwannomas occur unpredictably without known familial predisposition (Plotkin & Blakeley, 2022).

Environmental and Other Potential Factors: While environmental exposure has been proposed as a potential factor, robust evidence linking specific chemicals, toxins, or environmental factors to MPNST remains limited. Currently, inherited genetic predisposition (especially NF1) and prior therapeutic radiation are considered the predominant and most clearly established risk factors.

In summary, malignant schwannomas (MPNSTs) primarily occur due to genetic predispositions, particularly NF1, and prior radiation exposure. Sporadic cases also arise from isolated genetic mutations whose causes remain uncertain.

Symptoms of Malignant Schwannoma

Malignant schwannoma, or malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), presents with symptoms that largely depend on the tumor’s size, location, and extent of local invasion. These tumors arise from peripheral nerves and can affect any part of the body, but they most commonly appear in the extremities, trunk, head, neck, or deep soft tissues.

The hallmark symptom is a rapidly enlarging, painful mass. Unlike benign schwannomas, which are typically slow-growing and painless, malignant schwannomas grow quickly and often cause discomfort or deep-seated pain. The pain may be constant and worsen at night or with activity. Neurological symptoms such as numbness, tingling, burning, or weakness may occur when the tumor compresses or invades nearby nerves. This is particularly common when the tumor is located along major nerve pathways like the brachial plexus or sciatic nerve (Widemann & Italiano, 2018).

In some cases, motor deficits or loss of function may develop if the tumor affects motor nerves. For example, a lesion near the spine or major limb nerve roots may cause limb weakness or gait abnormalities. When MPNSTs arise in the head and neck, symptoms can include hoarseness, facial numbness, visual changes, or swallowing difficulties, depending on which cranial nerves are involved (Evans et al., 2021).

Because MPNSTs may grow aggressively, local invasion into surrounding tissues such as bone, muscle, or organs can lead to secondary symptoms like swelling, restricted range of motion, or systemic signs such as fatigue or unintended weight loss, especially in advanced cases. In patients with Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), malignant transformation of a pre-existing plexiform neurofibroma may be indicated by a sudden increase in size, new-onset pain, or neurologic deficits. These warning signs warrant urgent evaluation.

In summary, the most common symptoms of malignant schwannoma include a rapidly growing painful mass, nerve-related sensory or motor deficits, and systemic signs in advanced stages. Prompt imaging and biopsy are essential for early diagnosis and management.

Diagnosis of Malignant Schwannoma

Diagnosing malignant schwannoma, or malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), requires a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and histopathological confirmation. Because these tumors can mimic other soft-tissue sarcomas or benign nerve sheath tumors, accurate diagnosis is critical for determining appropriate treatment. The diagnostic process typically begins with clinical suspicion, often based on a rapidly enlarging, painful mass. This is especially concerning in patients with Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) who have a pre-existing plexiform neurofibroma that suddenly changes in size or becomes painful (Evans et al., 2021).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is the imaging modality of choice. MPNSTs often appear as large, heterogeneously enhancing, and poorly defined soft-tissue masses on MRI. Key features that suggest malignancy include irregular margins, necrosis, perilesional edema, and infiltration into surrounding tissues (Widemann & Italiano, 2018). However, imaging cannot definitively distinguish between benign and malignant peripheral nerve tumors. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) using 18F-FDG may support the diagnosis by highlighting areas of high metabolic activity, which correlate with malignancy. High standardized uptake values (SUVs) on PET imaging can help differentiate MPNST from benign schwannomas or neurofibromas, particularly in NF1 patients (Ferner et al., 2008).

Core needle biopsy or incisional biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. Histologically, MPNSTs are characterized by dense cellularity, mitotic figures, nuclear atypia, geographic necrosis, and fascicular growth patterns. Immunohistochemistry often shows loss of S100 protein expression, which distinguishes MPNSTs from benign schwannomas that typically express S100 diffusely (Louis et al., 2021). Molecular studies may assist in complex cases. Loss of NF1 gene function, mutations in TP53 or CDKN2A/B, and expression of SOX10, H3K27me3 loss, or PRC2 complex mutations may support the diagnosis of MPNST (Reuss et al., 2020).

In summary, the diagnosis of malignant schwannoma involves a multimodal approach combining MRI and PET imaging, tissue biopsy, histopathological assessment, and immunohistochemistry. Early recognition is essential to guide surgical and oncologic management.

Treatment of Malignant Schwannoma

The treatment of malignant schwannoma—more accurately termed malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST)—is complex and typically requires a multimodal approach, with surgery as the primary curative modality. Given the aggressive nature of MPNST and its high rate of local recurrence and metastasis, early diagnosis and coordinated care at specialized sarcoma centers are essential (Widemann & Italiano, 2018).

Surgical Resection

Complete surgical excision with negative margins (R0 resection) is the cornerstone of treatment. Wide local excision aims to remove the tumor entirely along with a rim of healthy surrounding tissue. Achieving negative surgical margins is the most important predictor of local control and overall survival. Incomplete resections (R1 or R2) are associated with a significantly higher risk of recurrence (Evans et al., 2021). Limb-sparing surgery is often preferred when feasible, but amputation may be considered for tumors that extensively involve critical structures.

Radiation Therapy

Adjuvant radiation therapy is frequently recommended, especially when surgical margins are close or positive, or when tumors are large or high-grade. Radiation can reduce the risk of local recurrence, although its impact on overall survival remains limited. Preoperative radiation may also be used to shrink the tumor and improve resectability (Widemann & Italiano, 2018). Modern conformal techniques like IMRT (intensity-modulated radiotherapy) help limit radiation to surrounding normal tissues.

Read More About Radiotherapy for Brain Tumor on Oncodaily

Chemotherapy

The role of chemotherapy in MPNST is less clearly defined. While not curative on its own, chemotherapy may be considered for high-grade, metastatic, or unresectable tumors, or in the neoadjuvant (pre-surgical) setting. Common regimens include ifosfamide and doxorubicin, similar to those used in other soft tissue sarcomas (Reuss et al., 2020). In NF1-associated MPNSTs, response to chemotherapy may be lower compared to sporadic tumors.

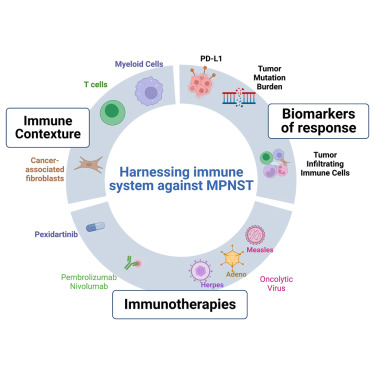

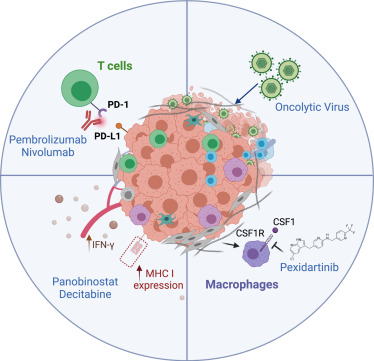

Targeted Therapy and Investigational Approaches

No targeted therapy has been approved for MPNST as of 2025. However, clinical trials are exploring molecularly targeted therapies based on genetic alterations (e.g., MEK inhibitors in NF1-mutant tumors) and immunotherapy approaches such as checkpoint inhibitors. While these strategies remain experimental, they offer hope for patients with recurrent or refractory disease (Plotkin & Blakeley, 2022).

Prognosis of Malignant Schwannoma

The prognosis of malignant schwannoma, or malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), is generally poor compared to other soft tissue sarcomas, due to its aggressive nature, high recurrence rate, and potential for distant metastasis. Prognostic outcomes are influenced by multiple factors, including tumor size, location, surgical margins, genetic background (particularly NF1 status), and histological grade.

Overall Survival Rates

The reported 5-year overall survival (OS) for MPNST ranges from 35% to 60%, depending on patient and tumor characteristics (Widemann & Italiano, 2018). Patients without Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) tend to have better outcomes than those with NF1-associated MPNST, as NF1-related tumors are more likely to be multifocal, high-grade, and resistant to therapy (Evans et al., 2021). Prognostic Factors are:

- Tumor Size: Tumors larger than 5 cm at diagnosis are associated with significantly worse prognosis.

- Surgical Margins: Complete resection with negative margins (R0) is the strongest predictor of long-term survival. Local recurrence is common when margins are positive (R1/R2).

- NF1 Status: Patients with NF1-associated MPNST have a poorer prognosis than sporadic cases, with higher rates of recurrence and lower response to chemotherapy (Reuss et al., 2020).

- Histologic Grade: High mitotic index, necrosis, and cellular atypia correlate with more aggressive disease and worse survival.

- Metastasis at Diagnosis: The presence of distant metastasis (especially to the lungs) at the time of diagnosis dramatically reduces survival expectations.

Recurrence and Metastasis

Local recurrence rates are high, occurring in 40–65% of patients even after surgery and radiation. Distant metastases, most commonly to the lungs, liver, and bones, occur in approximately 40–50% of patients and are a major cause of mortality (Widemann & Italiano, 2018).

Long-Term Management

Long-term surveillance is essential. Regular imaging (MRI of the primary site and CT of the chest) every 3–6 months for the first 2–3 years post-treatment is recommended due to the high risk of recurrence. For patients with localized, completely resected, low-grade tumors, prognosis is more favorable, and long-term survival is possible.

In summary, while some patients—especially those with sporadic, completely resected, and smaller tumors—may achieve durable remission, malignant schwannoma remains a high-risk malignancy with limited curative options once it recurs or metastasizes.

2025 Advances in Malignant Schwannoma Research and Treatment

As of 2025, the management of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs)—particularly those associated with Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)—is entering a new era, driven by genomic insights, targeted therapies, and novel clinical trial strategies. While MPNST remains a challenging malignancy, several promising advances are underway:

MEK Inhibitors in NF1-Associated MPNST

Given the dysregulation of the RAS/RAF/MEK pathway in NF1-related tumors, MEK inhibitors like selumetinib have shown efficacy in benign plexiform neurofibromas. In 2025, ongoing trials are evaluating whether MEK inhibition can delay or prevent malignant transformation, or serve as a neoadjuvant strategy to shrink MPNST prior to surgery (Gross et al., 2024).

Genomic Stratification for Precision Therapy

Next-generation sequencing has enabled molecular subtyping of MPNSTs, identifying actionable mutations such as CDKN2A/B deletions, PRC2 inactivation, and TP53 mutations. Clinical trials are now exploring CDK4/6 inhibitors, EZH2 inhibitors, and immune checkpoint inhibitors in genetically defined subgroups, with early data suggesting potential synergy in tumors with specific epigenetic signatures (Reuss et al., 2020; NCI, 2025).

Immunotherapy and Combination Approaches

Although MPNST is generally considered an “immune-cold” tumor, 2025 trials are combining PD-1 blockade with MEK inhibitors or radiation therapy to enhance immune activation. Trials like SARC045 are assessing pembrolizumab in sarcoma subtypes, including MPNST, particularly in tumors with mismatch repair deficiency or high tumor mutational burden.

Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) for Surveillance

Liquid biopsy technologies to detect ctDNA from NF1-deficient or TP53-mutant clones are being developed for monitoring disease recurrence or transformation in high-risk NF1 patients. These assays may soon offer a non-invasive method for early intervention and treatment adaptation, especially in patients under routine surveillance.

Novel Radiation Techniques

Advanced proton beam therapy and image-guided stereotactic radiation are being tested in MPNST to improve local control while minimizing damage to surrounding tissue—especially critical for tumors near the spine or brachial plexus.

Ongoing Clinical Trials 2025

NCT05552444 – A Phase II trial of selumetinib and everolimus in advanced NF1-related MPNST.

NCT04652981 – A trial of EZH2 inhibition in PRC2-deficient MPNSTs.

NCT04362075 – A study evaluating combination immunotherapy in advanced sarcomas, including MPNST.

NCT04013869 – Evaluating ctDNA surveillance in soft tissue sarcomas for early detection of recurrence.

In summary, 2025 marks a turning point in MPNST research, with precision oncology, immunotherapy combinations, and early detection technologies offering hope in a disease long defined by limited treatment options and poor outcomes.

You Can Watch More on OncoDaily Youtube TV

Written by Armen Gevorgyan, MD

FAQ

What is a malignant schwannoma?

A malignant schwannoma, or malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), is a rare and aggressive cancer arising from the protective lining of peripheral nerves.

How is a malignant schwannoma different from a benign schwannoma?

Benign schwannomas are slow-growing and non-invasive, while malignant schwannomas are fast-growing, invasive, and can metastasize to other parts of the body.

What causes malignant schwannoma?

It can occur spontaneously, after prior radiation exposure, or from transformation of benign plexiform neurofibromas, especially in people with Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

Who is at risk for developing MPNST?

Individuals with NF1, those with prior radiation therapy, and adults between ages 20 and 50 are at increased risk.

What are the symptoms of malignant schwannoma?

Common symptoms include a growing mass, pain, numbness, weakness, or functional loss near the affected nerve.

How is MPNST diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves MRI or CT imaging, followed by biopsy and histopathological examination, including molecular and immunohistochemical analysis.

What is the standard treatment for malignant schwannoma?

Treatment usually includes surgical removal with wide margins, often followed by radiation. Chemotherapy may be used in high-risk or metastatic cases.

Can MPNST be cured?

If caught early and fully removed, some cases can be cured. However, the recurrence and metastasis rates are high, especially in NF1-related cases.

What is the prognosis for malignant schwannoma?

Five-year survival ranges from 35% to 60%, depending on factors such as tumor size, NF1 status, metastasis, and surgical margins.

What new treatments are being explored in 2025?

Current trials are investigating MEK inhibitors, immunotherapy combinations, EZH2 inhibitors, and liquid biopsy-based surveillance for early detection.