In a post by Sebastian Schmidt, Head of Strategy and Medical Affairs Computed Tomography at Siemens Healthineers, on LinkedIn:

“Lung cancer screening saves lifes – but how many? And how long?

My recent post generated some more questions, time to add some explanations.

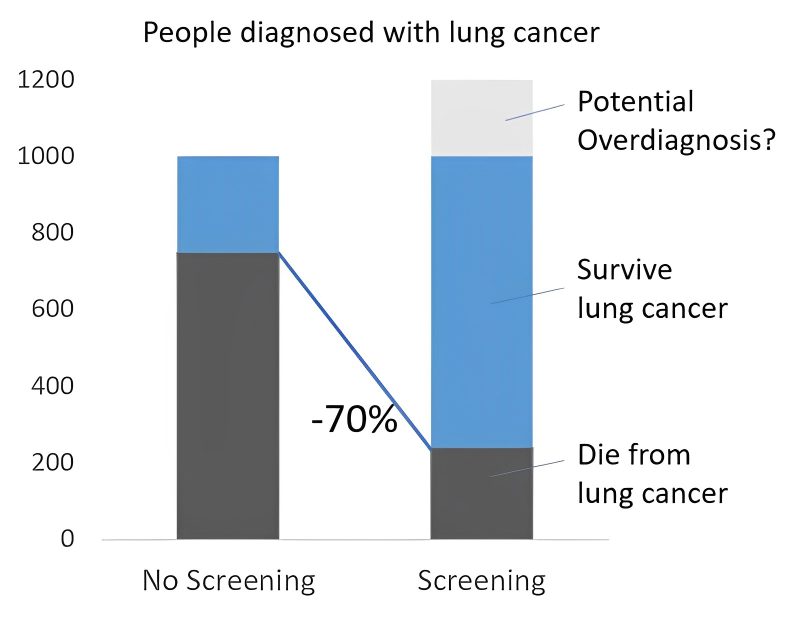

If we look at long-term data of real-world-programs (e.g. I-ELCAP that Claudia Henschke showed at the RSNA or in her 2006-NEJM paper), we find a LC-specific mortality in a screened population around 20% (80% survival). Outside screening, we see below 25% survival, 75% mortality. Of 1000 people diagnosed with lung cancer outside screening, >750 die, within screening, ~200 die. A >70% reduction in mortality.

Then we hear about a 20% reduction in LC-specific-mortality shown by the NLST, resp. 26% shown in NELSON. Obviously a different number. Why?

Now I hear people shout “overdiagnosis”. Overdiagnosis is inherent to screening, in fact, to any kind of diagnostics – illustrative is the extreme example of a person receiving a (correct) diagnosis of cancer and being hit over by a bus the next day. In clinical practice, we rarely see overdiagnosis in lung cancer – without screening, most people with lung cancer die from lung cancer, not with lung cancer. Different from prostate cancer.

Overdiagnosis in LCS is estimated at 18-20% (Patz et al, Ebell et al). A relevant number but not explaining the difference: Assuming 20% overdiagnosis, of 1000 people in screening 200 would be overdiagnosed, of the remaining 800, 240 die from lung cancer. 70% reduction.

To solve the riddle, let’s have a look at the purpose and design of the two largest RCTs, NLST and NELSON. Purpose was to decide on screening programs, therefore a threshold of 20% resp. 25% was set in advance – above this threshold, lung screening programs were seen as justified. This was a deliberate decision. The trials were designed to provide a binary answer: Below or above threshold. Indeed, data collection was ended when the threshold was reached. So even if the real mortality reduction would be 75%, the result of the trial would have been “above 20%”, what it was. This is often misunderstood and interpreted wrongly, even in scientific publications.

A hypothetical study to assess the real mortality reduction would need to replicate real screening programs, with annual CT scans over 25 years and follow-up until all participants died from any cause. Of course, such a study is practically impossible and unethical – unreasonable delay to start screening. That’s why the RCTs used a few CT scans and then limited follow-up. This certainly underestimates mortality reduction, as after the scanning period, participants show up with symptomatic lung cancer again. Still, it fits the purpose of the trials, just doesn’t allow the conclusion that the actual mortality reduction is only 20%/25%.

Conclusion: There is no contradiction between the high LC-specific mortality reduction seen in real-world data of screened population vs. non-screened and the outcome of the RCTs. The perceived difference is due to a wrong understanding of the purpose, design and results of the RCTs.”

Source: Sebastian Schmidt/LinkedIn