How Aging Populations Are Reshaping Global Cancer Trends or The Silent Shift

As the global population approaches 8 billion in 2025, an unprecedented demographic transition is altering the cancer landscape: approximately 6 billion individuals are adults (18+), and within this group, around 750 million are considered “older adults,” defined as those aged 65 and above. This cohort is set to expand due to rising life expectancy and falling birth rates, particularly in both developed and developing nations. Today, older adults comprise the majority of new cancer diagnoses and deaths signifying what experts call a “silent shift” in global health.

In high-income countries, an estimated 60–70% of all cancer cases occur among those 65 or older, while lower-income regions, though traditionally younger, are now experiencing the most rapid increases in their aged populations and corresponding cancer burdens.

The link between aging and cancer is anchored in complex biology: as people age, genetic mutations accumulate, and the efficiency of DNA repair mechanisms wanes. The body’s immune system becomes less effective at identifying and destroying abnormal cells. These internal changes are compounded by external societal developments. Improved health systems allow more people to live into advanced age, inadvertently increasing the pool at risk for cancer. Meanwhile, disparities in healthcare access influence outcomes: developed regions benefit from robust cancer detection and treatment, whereas middle and low-income countries often lack such infrastructure, amplifying poor prognoses as populations age.

Patterns of cancer types also reflect these dynamics. Lung, colorectal, breast (in women), prostate (in men), and stomach cancers are notably prevalent among older adults, but their distribution shifts with regional lifestyle factors, genetics, and healthcare equity. The demographic transformation unfolding worldwide demands urgent adaptation in healthcare policy, research, and cancer prevention to support the unique needs of a rapidly aging and increasingly cancer-prone population. Furthermore, readers will gain insights into which cancer types are most prevalent among older populations, revealing important patterns and differences across the globe, all supported by the latest data and scientific understanding.

Why Does Aging So Strongly Influence Cancer Risk?

Aging is a fundamental driver of cancer risk, underpinned by complex biological mechanisms that accumulate over time. Cellular DNA damage accrues due to both intrinsic processes, such as replication errors, and extrinsic factors like environmental carcinogens. Advancing age impairs DNA repair capacity and leads to the buildup of senescent cells, which secrete a pro-inflammatory milieu known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). This SASP promotes a microenvironment conducive to tumor progression despite its role in early tumor suppression. Immune senescence further diminishes immunosurveillance, reducing the clearance of emerging malignant cells and enabling tumor immune evasion. Autophagy exhibits a dual role, maintaining cellular homeostasis while allowing cancer cell survival during therapeutic stress, complicating treatment responses in older individuals.

Recent studies emphasize these aging-related biological changes as critical targets for tailored cancer prevention and therapeutic strategies. For instance, Lee et al. (2022) in Nature Reviews Cancer highlight how SASP factors create a pro-tumorigenic niche that fuels cancer progression in aged tissues [Lee et al., Nat Rev Cancer, 2022]. Demaria et al. (2021) discuss immune senescence’s role in impairing the elimination of pre-malignant cells, proposing immune rejuvenation as a viable approach (Cancer Cell, 2021). Moreover, Galluzzi et al. (2020) review the paradoxical function of autophagy in cancer, suggesting its modulation as a therapeutic avenue in age-associated malignancies (Cell, 2020). Collectively, these insights underscore the necessity of integrating aging biology into oncologic care and research.

How Do Regional and Socioeconomic Factors Shape Cancer Trends in the Elderly?

Global disparities in cancer epidemiology among older adults are profoundly influenced by a complex interplay of healthcare infrastructure, socioeconomic status, and region-specific lifestyle and environmental exposures. In high-income countries, robust healthcare systems facilitate widespread implementation of cancer screening programs and early diagnostic services, which contribute to higher reported cancer incidence rates among the elderly. This apparent increase in incidence is, in part, a reflection of enhanced detection capabilities and longer life expectancy, allowing cancers to be diagnosed at earlier, potentially more treatable stages.

Consequently, these regions often report improved survival outcomes and reduced mortality despite the growing cancer burden.

low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) face significant structural barriers that impede timely cancer diagnosis and treatment in older populations. Limited availability of diagnostic technologies, scarcity of specialized oncology services, and inadequate healthcare funding contribute to delayed presentation and advanced-stage diagnoses. These factors, coupled with restricted access to effective therapies, result in disproportionately higher cancer mortality rates in elderly patients, despite often lower reported incidence figures. The underreporting of cancer cases in these regions further complicates accurate epidemiological assessments.

Moreover, variations in the prevalence of key modifiable risk factors such as tobacco consumption, dietary patterns, infectious agents (e.g., Helicobacter pylori, hepatitis viruses), and environmental carcinogens further modulate cancer incidence and mortality profiles across regions. For example, higher rates of tobacco use in certain populations elevate lung and head and neck cancer risks, while endemic infections contribute to elevated liver and stomach cancer burdens in others.

This heterogeneity underscores the critical need for regionally tailored public health strategies that integrate demographic aging trends with the socioeconomic and environmental realities unique to each setting. Addressing these disparities requires strengthening healthcare infrastructure, expanding access to early detection and treatment, and implementing culturally appropriate prevention programs targeted at modifiable risk factors among aging populations worldwide.

Which Cancer Types Predominate in Older Adults and Why?

Epidemiological studies consistently show that certain cancers disproportionately affect older adults, with lung, colorectal, prostate, breast, and stomach cancers leading the list. These malignancies are not random but rather the culmination of lifelong exposures and biological changes that accompany aging. Over decades, cumulative contact with environmental carcinogens such as tobacco smoke, dietary toxins, and infectious agents sets the stage for malignant transformation. Meanwhile, intrinsic aging processes profoundly influence cancer development.

For instance, prostate and breast cancers are tightly linked to hormonal fluctuations that occur with advancing age, including shifts in estrogen and androgen levels that alter cellular growth dynamics. Gastrointestinal cancers, particularly colorectal and stomach cancers, often emerge from chronic inflammatory states fueled by persistent infections or dysbiosis of the gut microbiome, which disrupts mucosal integrity and immune surveillance.

At a cellular level, aging tissues experience mitochondrial dysfunction that impairs energy metabolism and increases oxidative stress, fostering DNA damage and genomic instability key drivers of tumorigenesis. Epigenetic alterations accumulate with age, reprogramming gene expression patterns in ways that can silence tumor suppressors or activate oncogenes. This intricate biological landscape means that cancers in older adults often differ not only in incidence but also in behavior and treatment response.

Recognizing these age-specific cancer profiles is critical. It calls for tailored screening protocols that account for the unique risk factors and biology of elderly patients, as well as therapeutic strategies that balance efficacy with the vulnerabilities of aging tissues. Such precision in oncology promises to improve outcomes and quality of life for the growing population of older cancer patients.

What Are the Therapeutic and Research Implications of Aging-Cancer Interactions?

The intersection of aging biology and oncology is rapidly emerging as a frontier rich with both challenges and therapeutic promise. Aging processes such as cellular senescence, a state of permanent cell cycle arrest triggered by DNA damage and other stresses play a paradoxical role in cancer. On one hand, senescence acts as a natural barrier to tumor development by halting the proliferation of damaged cells. On the other, the accumulation of senescent cells, especially after chemotherapy or radiation, can create a pro-inflammatory environment through the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which may promote tumor progression and therapy resistance.

Therapeutic strategies are now evolving to exploit this duality. For example, inducing senescence in cancer cells can stop their growth, while subsequent use of senolytic agents aims to selectively eliminate these senescent cells to prevent adverse effects. This “one-two punch” approach combining pro-senescence therapies with senolytics is gaining traction as a way to enhance treatment efficacy while minimizing toxicity, especially important for older patients who often have reduced physiological reserves.

Immune rejuvenation strategies are also being explored to counteract age-related immune decline, improving the body’s ability to clear senescent and malignant cells. Additionally, modulation of autophagy, the cellular recycling process, offers another promising avenue to sensitize tumors to therapy or protect normal tissues.

Yet, despite these advances, older adults remain underrepresented in clinical trials, limiting our understanding of how best to tailor treatments for this population with complex vulnerabilities. Integrating geroscience the study of aging biology with oncology research is essential to develop personalized therapies that improve survival and quality of life for elderly cancer patients. This approach not only addresses the biological intricacies of aging but also paves the way for more precise, less toxic cancer care in an aging world.

How Do Age-Related Differences Impact Cancer Survival Rates?

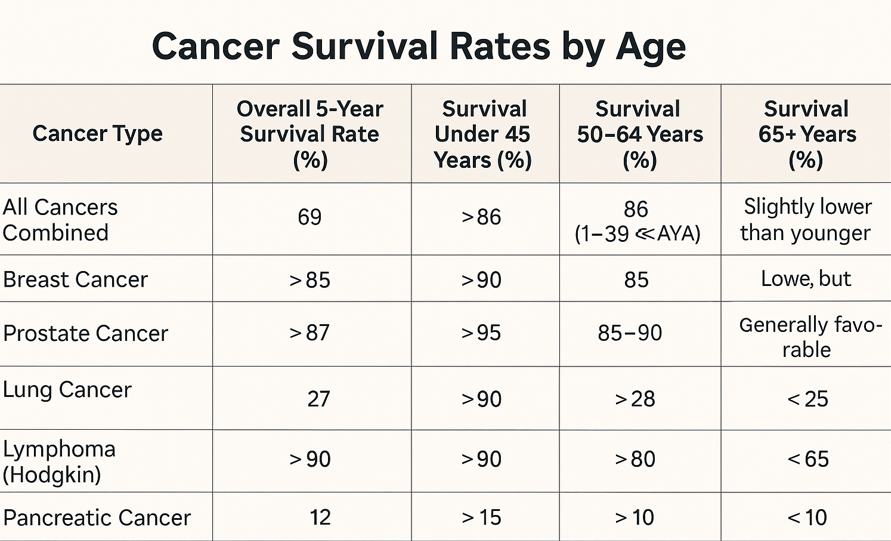

Cancer survival rates differ substantially across age groups, reflecting variations in biology, comorbidities, and treatment responses. According to the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Facts & Figures 2025, the overall 5-year relative survival rate for all cancers combined in the US is approximately 69% for people diagnosed from 2014 to 2020, but this varies widely by age and cancer type.

Younger adults generally have higher survival rates; for example, adolescents and young adults (AYAs, ages 15–39) have a 5-year survival rate of around 86% for all cancers combined. However, survival declines with advancing age: the majority of cancer survivors (32%) in the US are aged 70 to 79, and 21% are 80 or older, groups that often experience poorer outcomes due to frailty and comorbid conditions.

For specific cancers, survival disparities by age are pronounced. Lung cancer’s 5-year survival hovers around 27% overall, but younger patients (<45 years) experience better survival compared to older adults. In lymphoma, 5-year survival exceeds 90% in patients 15–40 years old but drops to roughly 65% after age 55. Breast and prostate cancers tend to maintain higher survival rates above 85%, though older patients still face relatively poorer prognoses due to late-stage diagnosis and treatment challenges. Pancreatic cancer survival is notably low in all groups but significantly worse in patients over 65, often due to advanced disease at diagnosis.

The increasing number of older cancer survivors expected to exceed 22 million in the US by 2035 highlights the urgent need to tailor treatment and survivorship care to accommodate age-related differences, improving outcomes and quality of life for this expanding population.

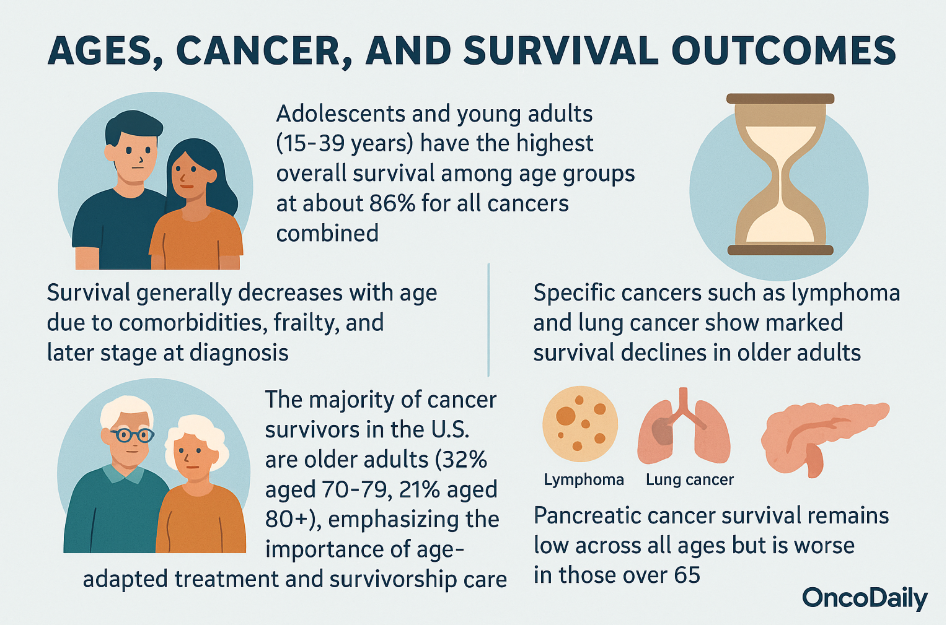

- Adolescents and young adults (15–39 years) have the highest overall survival among age groups at about 86% for all cancers combined.

- Survival generally decreases with age due to comorbidities, frailty, and later stage at diagnosis.

- The majority of cancer survivors in the U.S. are older adults (32% aged 70–79, 21% aged 80+), emphasizing the importance of age-adapted treatment and survivorship care.

- Specific cancers such as lymphoma and lung cancer show marked survival declines in older adults, while breast and prostate cancers maintain relatively higher survival rates but still show reduced outcomes in elderly patients.

- Pancreatic cancer survival remains low across all ages but is worse in those over 65, due largely to advanced disease on presentation.

What Preventive Measures Can Older Adults Take to Reduce Their Cancer Risk?

Preventive measures to reduce cancer risk in older adults encompass lifestyle modifications, regular screening programs, and appropriate vaccination strategies tailored to the aging population. Adopting healthy behaviors is one of the most effective ways to lower cancer risk as people grow older. Maintaining a healthy weight is crucial, as excess body weight is linked to increased risks of several cancers, including breast, prostate, colon, kidney, and lung cancers. Engaging in regular physical activity—such as walking, cycling, or swimming—for at least 150 minutes of moderate exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous activity weekly is recommended by leading cancer organizations.

A balanced diet rich in vegetables, fruits, beans, and whole grains, with limited consumption of red and processed meats, sugary foods, and alcohol, also contributes to cancer prevention. The Mediterranean diet, which emphasizes plant-based foods and healthy fats, has demonstrated protective effects against cancer development.

Avoiding tobacco use entirely, including smoking and chewing tobacco, remains critical since tobacco is a major contributor to many cancers in older adults. Alcohol consumption should be limited to moderate levels, defined as no more than one drink per day for women and two drinks per day for men. In addition to physical factors, managing stress through practices like meditation or yoga and maintaining strong social connections support overall health and reduce cancer risk.

Regular cancer screenings are vital for early detection and improving outcomes, although the recommendations for screening should be individualized based on a person’s age, overall health, and life expectancy. Commonly recommended screenings for older adults include mammography for breast cancer every two years between ages 50 and 74, colorectal cancer screening beginning at age 45 and continuing to 75 with various methods such as colonoscopy or stool tests, and annual low-dose CT scans for lung cancer in high-risk individuals aged 50 to 80 with a significant smoking history.

Cervical cancer screening is generally not recommended after age 65 if adequate prior screening has been performed, and prostate cancer screening using PSA tests should be considered on a case-by-case basis, especially for men under 70. It is important to recognize that for individuals with limited life expectancy or serious comorbidities, the potential harms of screening may outweigh benefits, making personalized assessment by healthcare providers essential.

Vaccination also plays a key role in cancer prevention for older adults. The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is most effective when given before sexual debut but may be considered in some adults aged 27 to 45 after consultation with their healthcare provider, particularly for those at elevated risk who were not previously vaccinated. Although the benefits of HPV vaccination diminish with age and do not treat existing infections, vaccination can still protect against future infections. The hepatitis B vaccine serves as a powerful tool in preventing chronic hepatitis B infection, a major cause of liver cancer worldwide. While vaccination has shown great success in younger populations, immune responses to the vaccine decrease with age.

You Can Also Read Could the HPV Vaccine Save Your Life? by Oncodaily

Thus, vaccination is recommended for individuals aged 60 and above only if they have significant risk factors, such as occupational exposure or chronic illness. Additionally, annual influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are essential for older cancer patients and survivors to reduce the risk of infections that can complicate cancer treatment and outcomes.

Written by Marine Marashlian

FAQ

Why does aging increase the risk of developing cancer?

Aging leads to the accumulation of genetic mutations, decreased DNA repair efficiency, immune system decline, and creates an environment that promotes tumor development.

What types of cancer are most common in older adults?

Lung, colorectal, breast (in women), prostate (in men), and stomach cancers are most prevalent among the elderly, influenced by both biological aging and lifelong environmental exposures.

How do cancer survival rates differ by age?

Younger patients generally have higher survival rates; survival declines with age due to factors like comorbidities, cancer biology, and treatment tolerance.

What regional and socioeconomic factors affect cancer incidence and outcomes among older adults?

High-income countries report higher incidence due to better detection and longer lifespan, while low- and middle-income countries face delayed diagnoses and higher mortality due to limited healthcare resources.

How does the biology of aging impact cancer treatment strategies?

Aging-related changes like cellular senescence, immune senescence, and altered autophagy necessitate personalized treatment approaches balancing efficacy and toxicity.

Are older adults adequately represented in cancer clinical trials?

No, older adults remain underrepresented, which limits evidence on optimal therapies and necessitates increased inclusion in research.

What challenges do healthcare systems face with an aging population and rising cancer cases?

Systems must adapt to increased cancer burden among older adults, requiring enhanced screening, tailored therapies, supportive care, and policy reforms to meet complex needs.

How do lifestyle and environmental exposures throughout life influence cancer risk in later years?

Cumulative exposures to tobacco, diet, infections, and carcinogens interact with aging biology to drive cancer development, emphasizing prevention across the lifespan.

-

Challenging the Status Quo in Colorectal Cancer 2024

December 6-8, 2024

-

ESMO 2024 Congress

September 13-17, 2024

-

ASCO Annual Meeting

May 30 - June 4, 2024

-

Yvonne Award 2024

May 31, 2024

-

OncoThon 2024, Online

Feb. 15, 2024

-

Global Summit on War & Cancer 2023, Online

Dec. 14-16, 2023