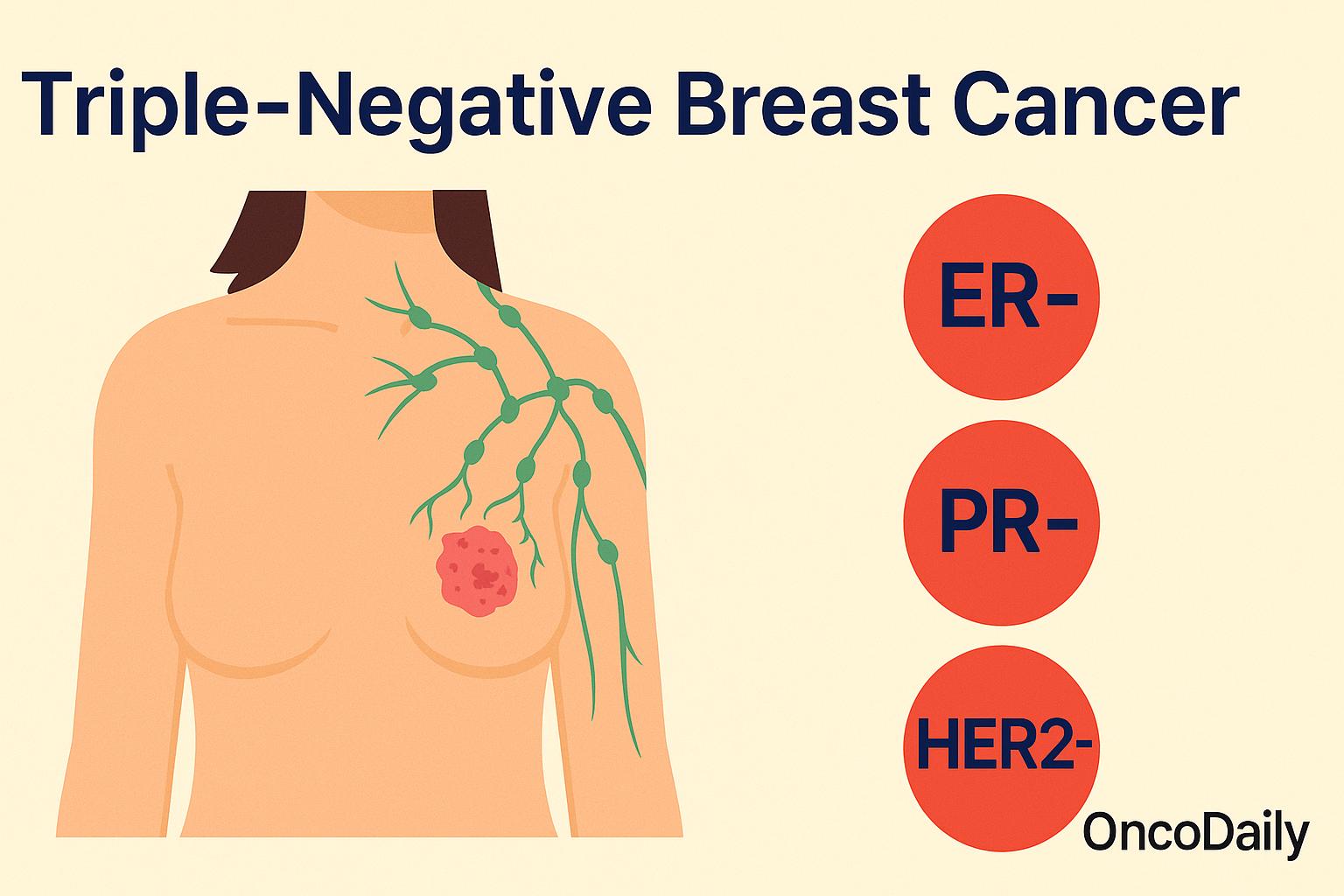

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a less common but more aggressive type of breast cancer that can be more difficult to treat than other forms. It gets its name because the cancer cells do not have three common features that are often used to guide treatment: estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), and HER2 protein.

This means that many of the targeted treatments used in other types of breast cancer, such as hormone therapy or HER2-targeted drugs, are not effective against TNBC. Although TNBC accounts for only about 10 to 15% of all breast cancers (American Cancer Society), it tends to grow faster, spread earlier, and has a higher chance of coming back after treatment—especially within the first few years.In this article, we’ll explore what makes triple-negative breast cancer unique, how it’s diagnosed, what treatment options are available, and the promising new therapies that are offering hope to patients today.

Who Is Affected by Triple-Negative Breast Cancer?

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive form of breast cancer that tends to affect certain groups of people more frequently than others. While anyone can develop TNBC, research has shown that it is more common in younger women, particularly those under the age of 40. Compared to other breast cancer types, TNBC is also more frequently diagnosed in women who are Black or Hispanic, and in individuals who carry mutations in the BRCA1 gene.

According to the American Cancer Society, about 10% to 15% of all breast cancers are triple-negative, but the risk is nearly twice as high for Black women compared to White women. This is especially important because TNBC tends to grow and spread more quickly than other types, and racial disparities in outcomes remain a serious concern. Even when accounting for access to care and treatment, Black women with TNBC often face higher mortality rates (American Cancer Society, 2024).

Genetics also play a key role. BRCA1 mutations, which interfere with the body’s ability to repair DNA damage, are strongly associated with triple-negative breast cancer. In fact, up to 69% of breast cancers in women with a BRCA1 mutation are triple-negative (Foulkes et al., New England Journal of Medicine, 2010). Because of this, genetic counseling and testing are often recommended for individuals diagnosed with TNBC, particularly if they have a family history of breast or ovarian cancer.

In addition to BRCA1, new genetic insights are emerging. A recent 2024 study highlighted by Reuters found six novel genetic variants associated with a significantly higher risk of TNBC, especially among women of African ancestry. Women who carried all six of these variants were shown to be over four times more likely to develop triple-negative breast cancer than those who did not have them. While age, race, and genetics can increase the risk, it’s important to remember that TNBC can affect anyone, even those without known risk factors. That’s why awareness, early detection, and equitable access to diagnosis and treatment are so essential—especially for populations who may be at higher risk but historically underserved in cancer care.

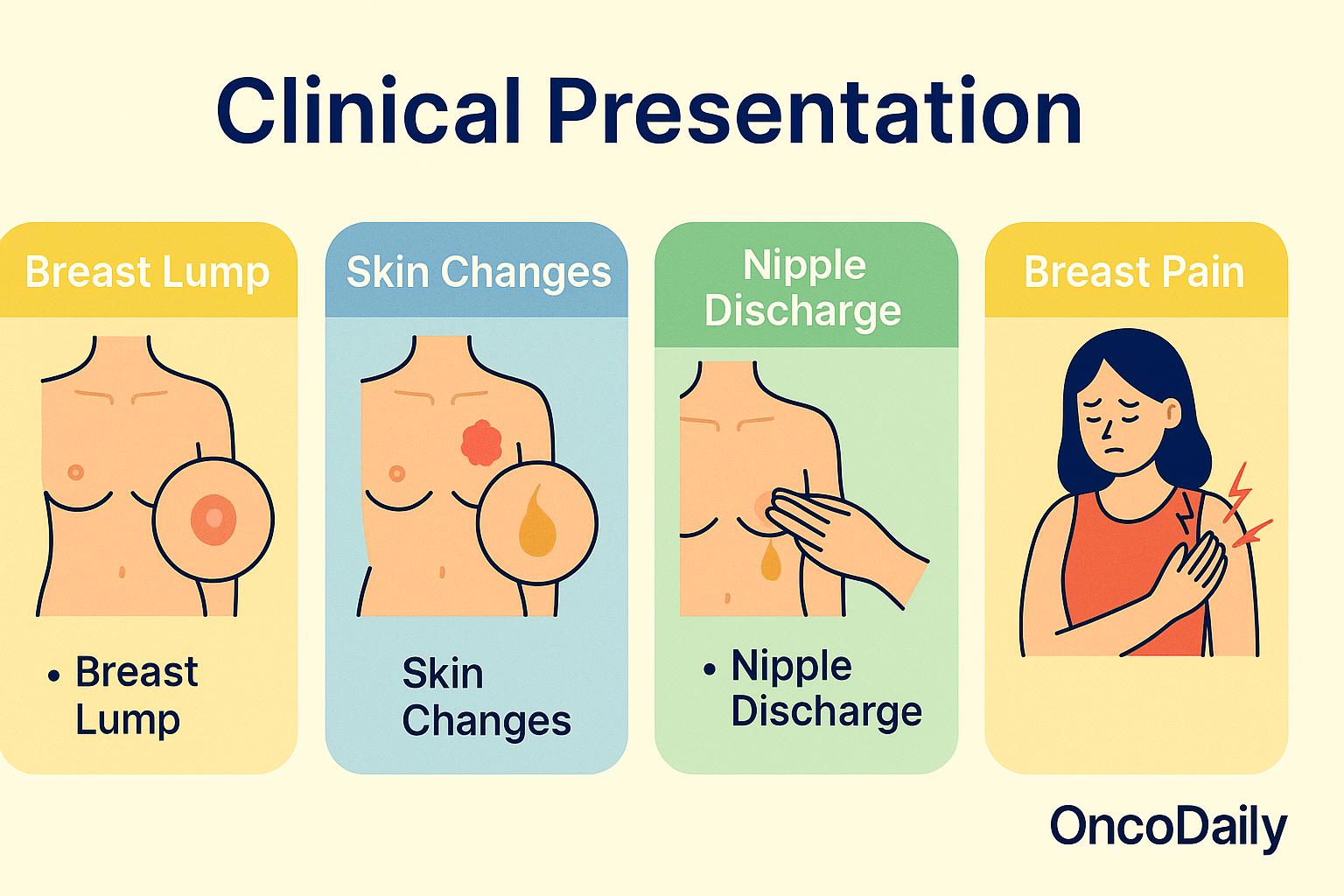

Clinical Presentation Of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) often presents with features that resemble other types of breast cancer, but its clinical course is notably more aggressive. Most patients with TNBC report discovering a palpable lump in the breast, which tends to grow rapidly and is often firm, non-tender, and irregular in shape. Unlike some slower-growing breast cancers, TNBC tumors can become noticeable within a relatively short timeframe. Changes in breast appearance—such as skin dimpling, redness, swelling, or nipple inversion—may also be present. In many cases, swelling of the lymph nodes under the arm (axillary lymphadenopathy) is detected either by physical exam or imaging, suggesting possible early spread.

Although these symptoms are common, it’s worth noting that TNBC can be asymptomatic in early stages, especially in younger women, which highlights the critical importance of routine screening, even in populations not typically considered high-risk. According to the American Cancer Society (2024), TNBC is more likely than other subtypes to be diagnosed at a more advanced stage due to its fast growth rate and lack of early detection markers such as hormone receptor positivity.

Perhaps one of the most distinct aspects of TNBC is its pattern of metastasis. Compared to hormone receptor-positive tumors, which tend to spread to bone, TNBC is more likely to metastasize to visceral organs, particularly the lungs, liver, and brain. A study by Lin et al. (Cancer, 2008) found that patients with TNBC have a higher risk of central nervous system metastases, often within the first three years after diagnosis. This early, aggressive metastatic behavior contributes significantly to TNBC’s poorer overall prognosis.

How Is TNBC Diagnosed?

Diagnosing triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) requires a stepwise approach that begins with clinical suspicion and proceeds through imaging, biopsy, and molecular profiling. Most patients with TNBC initially present with a breast mass or other changes in the breast, which are then evaluated using imaging techniques such as mammography and ultrasound. On mammograms, TNBC often appears as a high-density mass with ill-defined or spiculated margins. Ultrasound typically shows a solid, hypoechoic lesion with irregular or angular borders, suggestive of malignancy. For some patients—especially those with dense breast tissue or suspected multifocal disease—magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide additional diagnostic detail and improve detection sensitivity.

Once a suspicious lesion is identified, core needle biopsy is performed to obtain a tissue sample for histopathological examination. This biopsy is crucial not only to confirm malignancy but also to determine receptor status through immunohistochemistry (IHC). In cases of TNBC, the tumor cells test negative for estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), and HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2). The absence of these receptors defines the triple-negative phenotype and differentiates it from other subtypes that may benefit from hormonal or HER2-targeted therapies.

Following pathological confirmation, patients undergo staging procedures to evaluate the extent of the disease. This typically includes imaging of the chest, abdomen, pelvis, and sometimes the bones or brain, depending on symptoms and clinical suspicion. CT scans, PET-CT, and bone scans are commonly used to assess for distant metastases. Staging is performed using the AJCC TNM classification system, which incorporates tumor size (T), lymph node involvement (N), and presence of distant metastasis (M) to guide prognosis and treatment planning.

In a study by Chikarmane et al. (2013), published in AJR American Journal of Roentgenology, it was observed that TNBC is more likely than other breast cancer subtypes to present as a well-circumscribed mass without calcifications, particularly on mammography, which can mimic benign lesions and delay diagnosis. This highlights the importance of correlating imaging with clinical and pathological findings. Another study by Dogan et al. (2013) in Radiographicsemphasized the utility of MRI in assessing the extent of TNBC, particularly for surgical planning and detecting additional lesions not seen on conventional imaging.

Why Is TNBC More Challenging to Treat?

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) presents unique challenges in treatment compared to other breast cancer subtypes, primarily because it lacks the three main receptors—estrogen (ER), progesterone (PR), and HER2—that are commonly used as therapeutic targets in breast cancer. Hormone receptor-positive cancers can be treated with drugs like tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors, and HER2-positive cancers often respond well to HER2-targeted therapies such as trastuzumab. In contrast, TNBC does not express any of these receptors, which means that these targeted treatments are ineffective, leaving chemotherapy as the mainstay of systemic therapy.

Adding to the challenge, TNBC is known to be more aggressive in its clinical behavior. Studies have consistently shown that TNBC tends to grow and spread faster than other breast cancers. It has a higher rate of cell proliferation, as indicated by elevated Ki-67 expression, and often presents with a higher histological grade and more extensive lymphovascular invasion. These biological features contribute to its greater likelihood of early recurrence, particularly within the first three to five years after initial treatment.

What Are the Treatment Options?

Treatment for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) typically begins with chemotherapy, which remains the mainstay due to the tumor’s lack of hormone and HER2 receptors. In early-stage disease, chemotherapy is often given before surgery (neoadjuvant) to shrink the tumor and assess response. For advanced or metastatic TNBC, newer options include immunotherapy (such as checkpoint inhibitors for PD-L1–positive tumors), PARP inhibitors for patients with BRCA mutations, and antibody-drug conjugates like sacituzumab govitecan. Clinical trials are also exploring promising combinations of chemotherapy with targeted or immune-based therapies.

Chemotherapy For Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC)

Chemotherapy remains a cornerstone in the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), particularly due to the absence of hormone receptors and HER2 expression, which precludes the use of targeted therapies. TNBC is notably sensitive to chemotherapy, with significant responses observed in both early and advanced stages.

In early-stage TNBC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) is commonly employed to reduce tumor size before surgery. Studies have reported pathological complete response (pCR) rates ranging from 30% to 50%, indicating no residual invasive cancer detectable post-treatment. For instance, the GeparSixto trial demonstrated that adding carboplatin to standard NAC regimens increased pCR rates to approximately 53% in TNBC patients. In the metastatic setting, chemotherapy continues to play a pivotal role. Platinum-based chemotherapies, such as carboplatin and cisplatin, have shown efficacy, particularly in patients with BRCA mutations. A study published in the Annals of Oncology reported an objective response rate of 33.3% in TNBC patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy.

Immunotherapy For Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC)

Immunotherapy has emerged as a transformative approach in the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), a subtype lacking estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors, which traditionally limited targeted therapy options. Recent clinical trials have demonstrated significant benefits of incorporating immune checkpoint inhibitors, particularly pembrolizumab, into treatment regimens for both early-stage and advanced TNBC.

In early-stage, high-risk TNBC, the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-522 trial evaluated the addition of pembrolizumab to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy, followed by adjuvant pembrolizumab post-surgery. The study enrolled 1,174 patients with stage II or III TNBC. Results showed that the combination therapy led to a statistically significant improvement in pathological complete response (pCR) rates and event-free survival (EFS) compared to chemotherapy alone. Specifically, the estimated overall survival at 60 months was 86.6% in the pembrolizumab-chemotherapy group versus 81.7% in the placebo-chemotherapy group (P=0.002) . These findings support the integration of pembrolizumab into the standard treatment protocol for early-stage TNBC.

For patients with advanced or metastatic TNBC, the KEYNOTE-355 trial assessed the efficacy of pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy in tumors expressing PD-L1 with a combined positive score (CPS) ≥10. The study demonstrated that the addition of pembrolizumab resulted in a significant improvement in overall survival compared to chemotherapy alone. At 18 months, the estimated overall survival was 58.3% in the pembrolizumab-chemotherapy group versus 44.7% in the placebo-chemotherapy group . These results led to the FDA approval of pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive advanced TNBC.

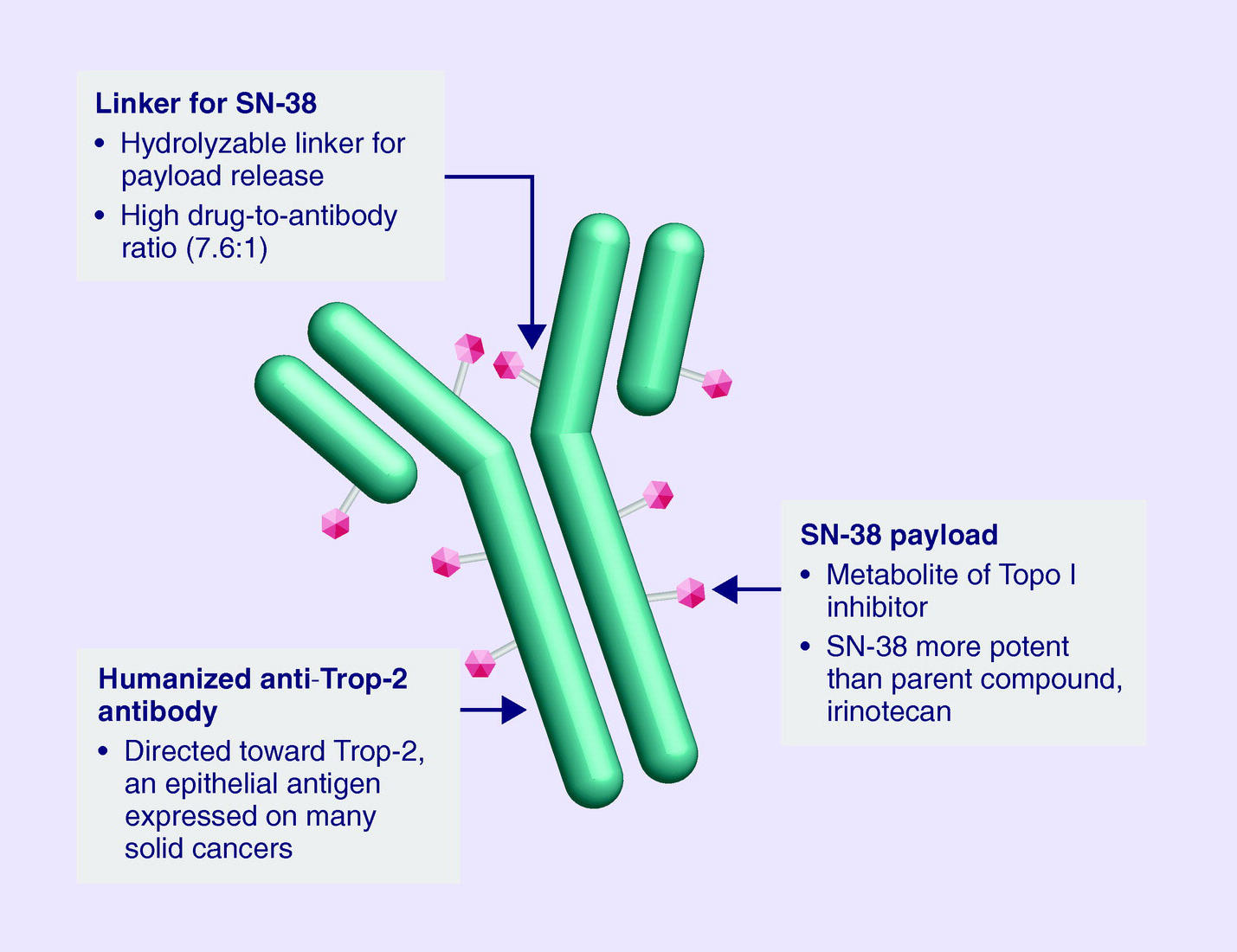

Further advancements have been observed with the combination of immunotherapy and antibody-drug conjugates. The ASCENT-04/KEYNOTE-D19 Phase 3 trial evaluated sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy) in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with previously untreated, PD-L1-positive, locally advanced or metastatic TNBC. The study demonstrated a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in progression-free survival compared to the combination of pembrolizumab and chemotherapy . This combination therapy offers a promising new option for patients with advanced TNBC.

Targeted therapy For Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC)

Targeted therapy has emerged as a pivotal advancement in the management of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), particularly for patients with specific genetic alterations or tumor characteristics. Unlike hormone receptor-positive or HER2-positive breast cancers, TNBC lacks these common targets, necessitating alternative therapeutic strategies.

One of the most significant breakthroughs in targeted therapy for TNBC involves the use of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, especially in patients harboring BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. These mutations impair the homologous recombination repair pathway, rendering cancer cells more reliant on PARP-mediated DNA repair mechanisms. Inhibiting PARP in these cells leads to the accumulation of DNA damage and subsequent cell death.

Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of PARP inhibitors in this context. For instance, the OlympiA trial, a phase III study, evaluated the efficacy of olaparib as adjuvant therapy in patients with germline BRCA-mutated, HER2-negative early breast cancer. The trial reported a 3-year invasive disease-free survival rate of 85.9% in the olaparib group compared to 77.1% in the placebo group, with a hazard ratio for invasive disease or death of 0.58 (95% CI, 0.41 to 0.82; P<0.001) .

In the metastatic setting, sacituzumab govitecan, an antibody-drug conjugate targeting Trop-2, has shown promise. The ASCENT trial, a phase III study, compared sacituzumab govitecan to standard chemotherapy in patients with metastatic TNBC who had received at least two prior therapies. The study found that sacituzumab govitecan significantly improved median progression-free survival (5.6 months vs. 1.7 months) and median overall survival (12.1 months vs. 6.7 months) compared to chemotherapy . These findings underscore the importance of genetic testing and molecular profiling in TNBC to identify patients who may benefit from targeted therapies. Ongoing research continues to explore additional targets and combination strategies to further improve outcomes in this challenging breast cancer subtype.

Surgery and Radiation for early-stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC)

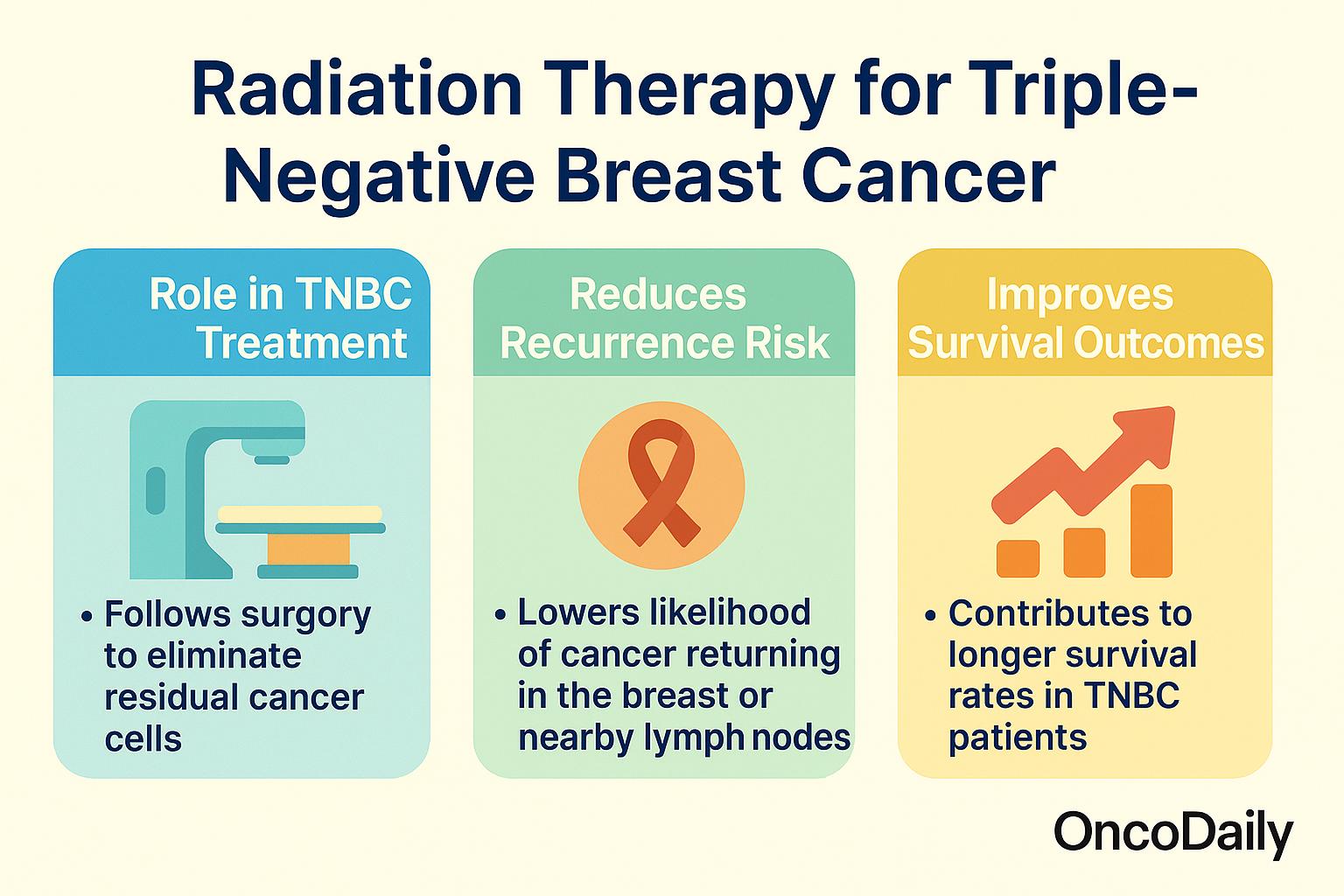

In early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), local treatment begins with surgery, followed in most cases by radiation therapy. The goal of this combined approach is to remove the tumor completely and minimize the risk of the cancer returning in the breast or surrounding lymph nodes. The two main surgical options are breast-conserving surgery (also called lumpectomy) and mastectomy. The choice depends on several factors, including tumor size and location, breast size, genetic risk, and patient preference.

Research has shown that breast-conserving surgery followed by radiation provides outcomes equivalent to mastectomy in appropriately selected patients. In a large population-based study by van Maaren et al. (2016), patients with early-stage breast cancer who received breast-conserving therapy with radiation had similar or better overall survival compared to those who underwent mastectomy. The benefit of radiation in this setting is well established. A meta-analysis by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) published in The Lancet (2011) found that post-lumpectomy radiation reduced the 10-year risk of any first recurrence from 35% to 19.3%, an absolute reduction of nearly 16%.

For patients undergoing mastectomy, radiation therapy—known as postmastectomy radiotherapy (PMRT)—may still be recommended, especially if the tumor is large or lymph nodes are involved. A study by Ohri et al. (2015) published in Annals of Surgical Oncology reported that PMRT significantly improved local control and disease-specific survival in TNBC patients with node-positive disease.

Additional evidence from the SEER database shows that radiotherapy improves both overall and breast cancer-specific survival in TNBC. In a study by Yang et al. (2019), patients with stage II-III TNBC who received radiotherapy after surgery had a significantly reduced risk of mortality compared to those who did not receive radiation. The 5-year breast cancer-specific survival rate was 91.4% in those receiving radiation, reinforcing its value even in aggressive subtypes like TNBC.

Taken together, these findings confirm that for most patients with early-stage TNBC, surgery followed by radiation therapy is essential for achieving optimal local control and long-term survival. Treatment decisions should be individualized, but strong evidence supports the use of radiation in both breast-conserving and certain postmastectomy settings to reduce recurrence and improve outcomes.

You Can Watch More on OncoDaily Youtube TV

Written by Toma Oganezova, MD

FAQ

What is TNBC?

Triple-negative breast cancer lacks estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors, making it harder to treat with standard targeted therapies.

Who is most affected?

It’s more common in women under 40, Black and Hispanic women, and those with BRCA1 mutations.

How is TNBC diagnosed?

Through a biopsy and lab tests showing absence of ER, PR, and HER2, followed by scans to check cancer spread.

Why is it harder to treat?

Because TNBC doesn’t respond to hormone or HER2-targeted therapies and tends to grow and spread faster.

What are the treatment options?

Chemotherapy, surgery, radiation, immunotherapy (like pembrolizumab), and targeted drugs for BRCA-positive patients.

Is chemotherapy effective?

Yes, especially in early-stage disease where it can shrink tumors before surgery and improve outcomes.

Can immunotherapy help?

Yes, especially for PD-L1–positive tumors. It can boost survival when combined with chemotherapy.

Are there new targeted therapies?

Yes—PARP inhibitors for BRCA mutations and antibody-drug conjugates like Trodelvy are showing strong results.

Do patients still need surgery and radiation?

Yes. Surgery removes the tumor, and radiation helps prevent it from returning.

What’s new in research?

Ongoing trials are testing new immune therapies, vaccines, and smarter targeted drugs to improve survival.